Cartimandua, or Cartismandua, was the queen of the Brigantes, an Iron Age Celtic people. She ruled in the 1st century CE, from about 43 to 69 CE. She is most well-known for betraying Caratacus, the chieftain of the Catuvellauni tribe and leader of an anti-Roman resistance, to the Romans. It is interesting that her more famous contemporary, Boudica, led a revolt against Rome in the 1st century and is remembered as a symbol of Celtic rebellion, while the pro-Roman Cartimandua has faded into relative obscurity. But who was Cartimandua, why did she betray Caratacus to the Romans, and what is her historical legacy?

Who Were the Brigantes?

The Brigantes were an Iron Age Celtic people who controlled territory in northern England in what is now known as Yorkshire. At the time, this land was referred to as Brigantia. Their organizational structure is somewhat unclear, as there are no written sources about them from before the Roman invasion of Britain. However, they were either one large tribe or a confederation of allied peoples occupying one area. Either way, they were one of the largest cohesive Celtic tribes in Britain.

It has been suggested that they were named after the goddess Brigantia, whose name has proto-Celtic roots in the word “Briganti” and means “The High One.” After the Roman invasion of Britain, Brigantia was identified with the Roman goddess Minerva, suggesting that she may have had similar associations with wisdom, victory, and strategy.

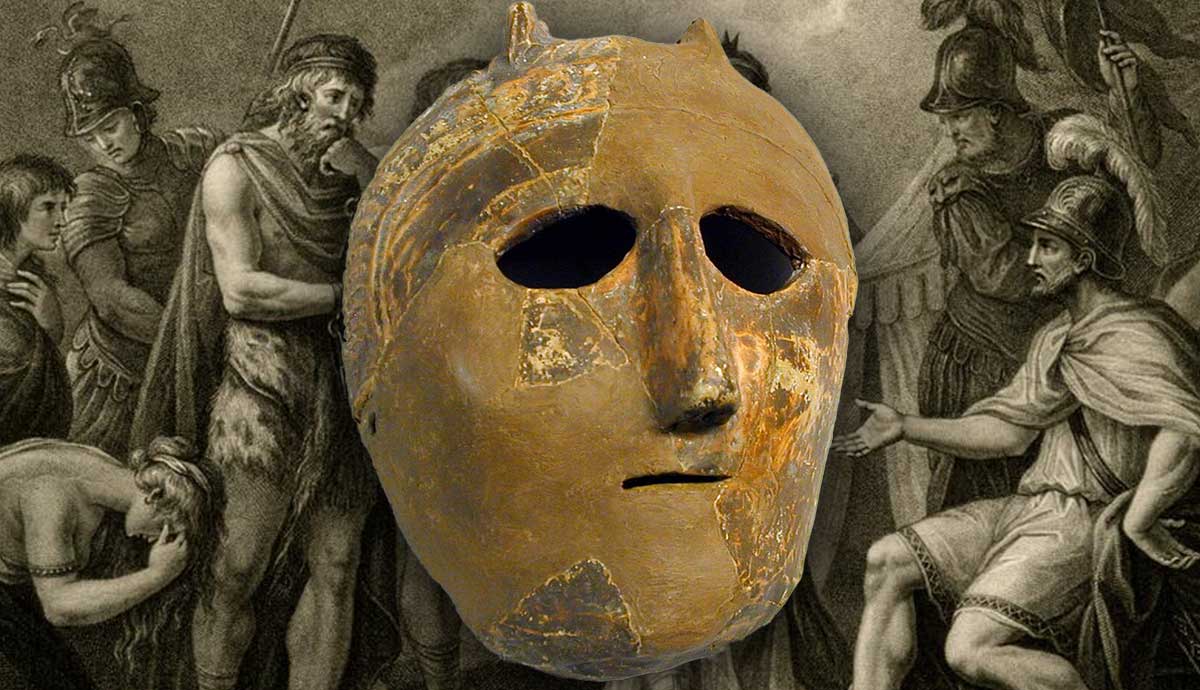

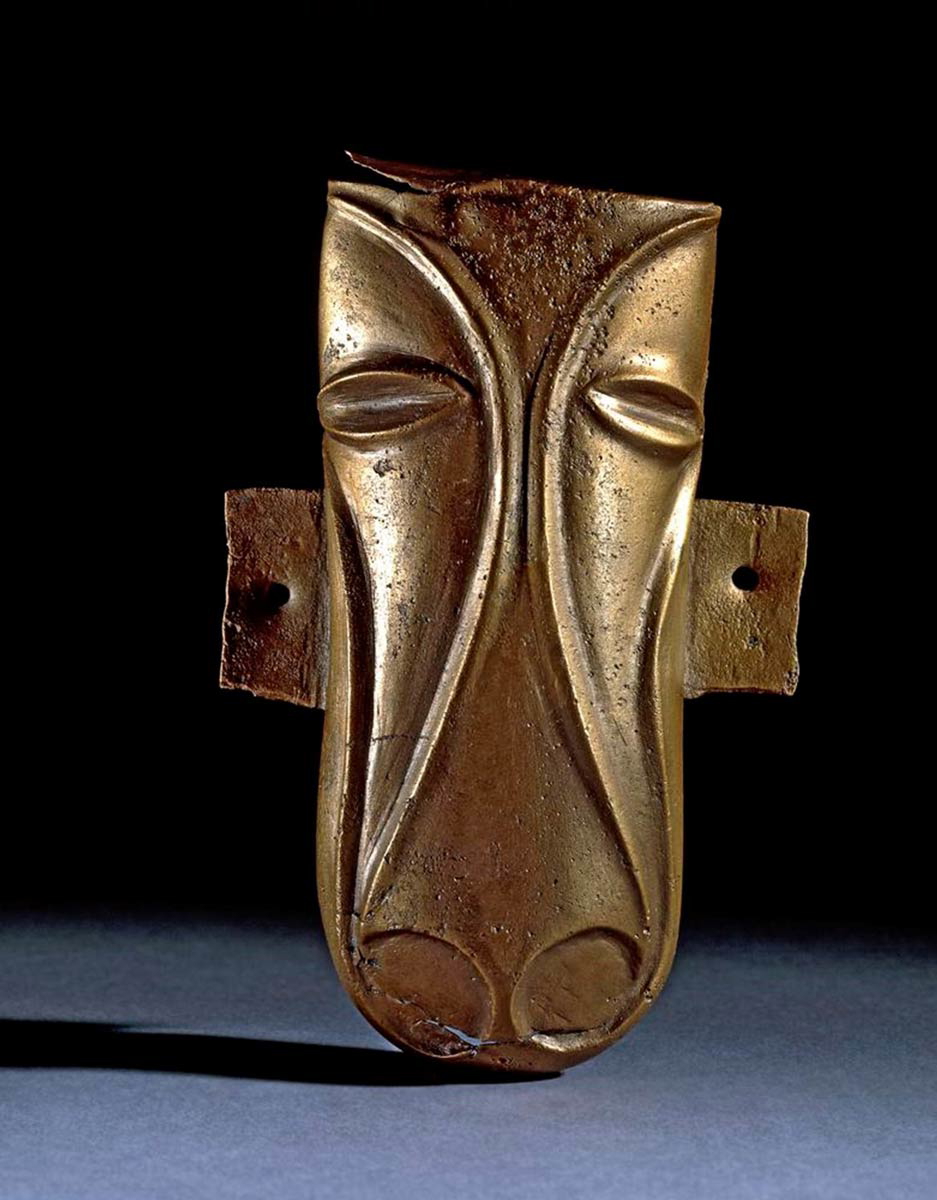

Though there are not many surviving written records about the Brigantes, there is much archaeological evidence of their existence in Britain. In 1845, a hoard of 140 objects known as the Stanwick Hoard was discovered at Stanwick, which is now believed to have been an important stronghold and royal center for the Brigantes. These objects, primarily metal, are believed to have been buried for religious reasons.

Queenship in the Celtic World

The role of Celtic women in Iron Age society is unclear, with questions about their potential upward social mobility. Those who were born to elite families certainly had more opportunities than elite women in other European societies. Many of the richest grave deposits that have been uncovered clearly belonged to women, which indicates that they could amass their own wealth. There is some suggestion of Celtic women being afforded military training, and Roman accounts of the Celts indicate some level of equality between men and women. However, it is unclear whether this was true or if Roman writers simply wished to differentiate the Celts from themselves.

However, the possibility of women holding meaningful positions of high status without a familial or marital connection to a man is unclear (Green 1995). The two known examples of Celtic queens, Boudica and Cartimandua, were married to equally powerful men, Prasutagus and Venutius, respectively. Both women lived during the 1st century CE and ruled around the same time. It is quite possible that they were not the only examples of Celtic queens and that we simply do not have a written record of the others.

Boudica was born in Camulodunum and was married to Prasutagus by age 18. Unlike Cartimandua, who is believed to have been the hereditary ruler of the Brigantes, Prasutagus was likely the official ruler, and Boudica became the singular ruler of the Iceni after Prasutagus’s death. Prasutagus was loyal to Rome, and Boudica only revolted after Rome ignored his wishes for part of his kingdom to go to their daughters. If this had not been the case, it is unclear whether Boudica would have held any anti-Roman sentiment. Her reign was short-lived and only lasted for the few years that her rebellion did. By contrast, Cartimandua may have ruled for over two decades.

Who Was Cartimandua?

Not much is known about Cartimandua’s life outside of her marriage to Venutius and betrayal of Caratacus. It is thought that she was of very high birth, and it is unclear whether her rulership over the Brigantes was hereditary or not. There is evidence to suggest that she was the granddaughter of King Bellnorix, which would indicate that she was from the ruling family and Venutius married in. He is often referred to as her “consort” in writings from the period, which offers more evidence that she was the rightful ruler of the two.

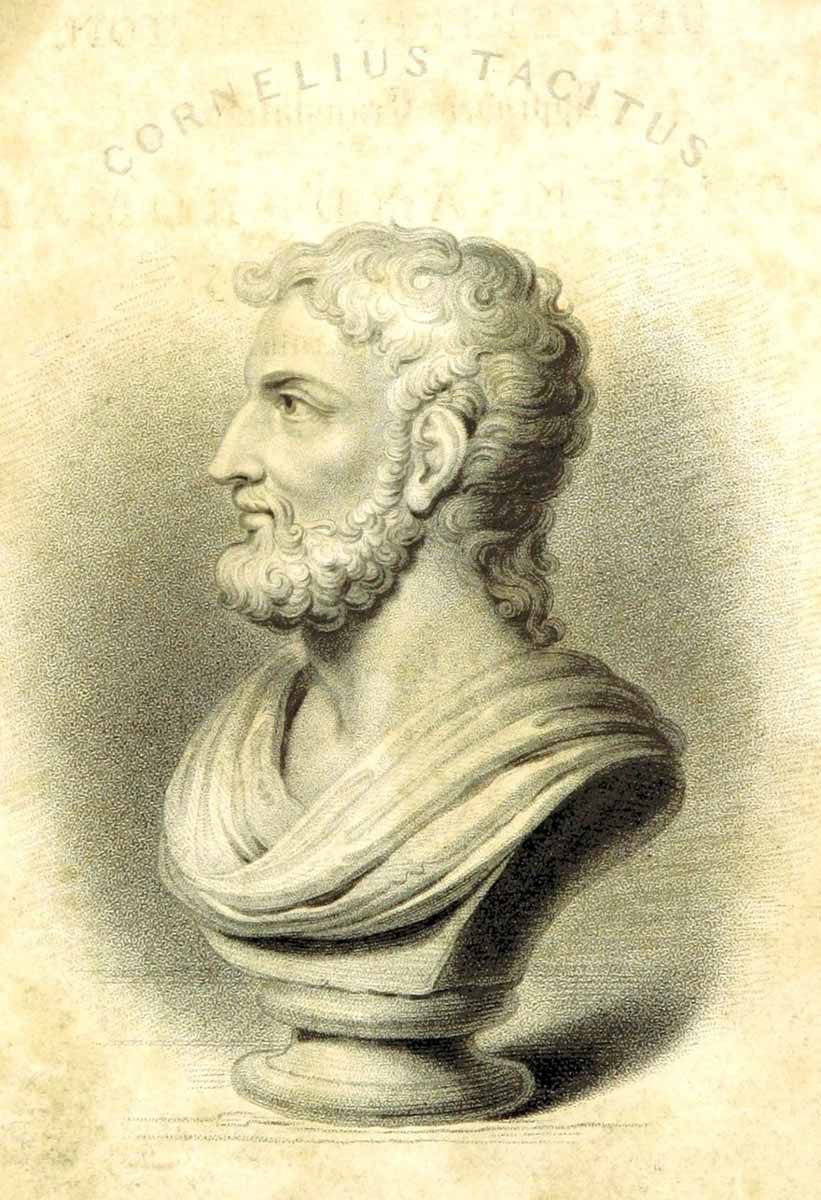

There is not much written about Bellnorix aside from his relation to Cartimandua, so as with many of the finer details about Iron Age Celtic figures, this family tree is murky at best. It is not recorded whether Cartimandua had any children with Venutius. Much of what is known about her comes from the writings of the Roman historian Tacitus, and according to him, she was an influential leader.

When Did Cartimandua Form Her Alliance With Rome?

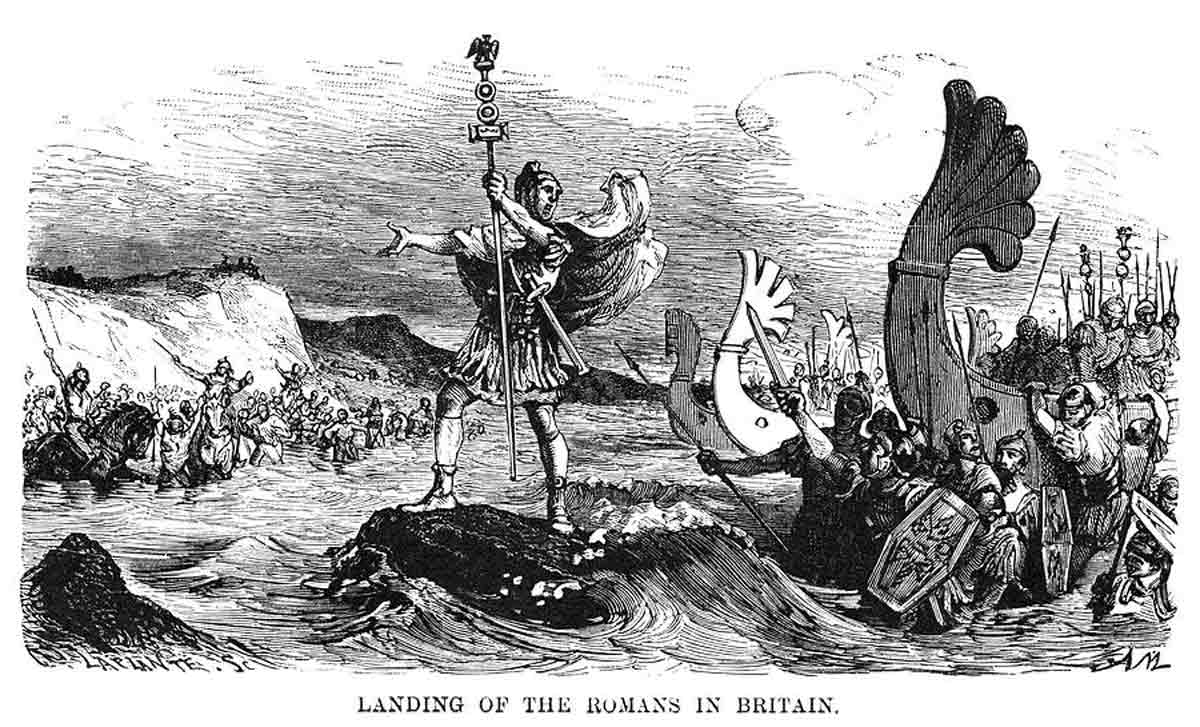

It is unclear exactly when Cartimandua came to power. She became queen either before the Roman invasion of Britain in 43 CE or soon afterward. When Claudius invaded Britain in 43, eleven Celtic kings surrendered to him at Camulodunum. Either Cartimandua or a family member was probably among this group, though the presence of a woman is not noted in the sources.

During her reign, Cartimandua chose to ally with Rome and cooperate with them, in contrast to other groups that chose to rebel against them and were subsequently killed. Though it is easy to imagine that a revolt, such as that led by Boudica in 60/61 CE, was the more honorable choice, one could argue that Cartimandua merely saw allying with Rome as the easiest way to protect her people.

Why Did Cartimandua Betray Caratacus?

The most significant event of Cartimandua’s reign was her betrayal of Caratacus c. 51 CE. Caratacus, son of the Celtic king Cunobelinus and king of the Catuvellauni, had been leading a rebellion against Rome, primarily leading his opposition from Wales. He was defeated by Roman governor Ostorius Scapula in 51 and, according to records, sought sanctuary with Cartimandua and the Brigantes.

Instead of helping Caratacus, Cartimandua turned him and his family over to the Romans. They were taken to Rome and “paraded in Claudius’s triumph” as a “spectacle of victory” over the Celtic Britons. Caratacus asked for clemency before Rome, which Claudius granted it. Caratacus lived out the rest of his life in Italy. Though Cartimandua was rewarded for her betrayal, it is believed that the act turned her people against her.

How Did Cartimandua’s Reign End?

Furthermore, Cartimandua had a messy divorce from Venutius during her reign. In 57 CE, Venutius led an anti-Roman faction against Cartimandua and attempted to seize power. It is unclear whether this event was the cause of the divorce or was spurred because of it. Cartimandua and Venutius clearly had differing views on handling the alliance with Rome. Cartimandua took several members of Venutius’s family hostage, provoking another attack, but Rome came to her aid and upheld her rule in Brigantia.

Cartimandua also took Venutius’s former armor-bearer, Vellocatus, as her new lover during this time (Green 1995). This development is said to have angered her people further after the events with Caratacus. Again, it is unclear whether this relationship had any bearing on Venutius’s rebellion, but according to Tacitus, it is at least believed to have been a factor in another attempt of his to seize power in 69 CE. This time, Venutius was successful. Rome was enduring a civil war after the death of the emperor Nero and was unable to send aid to Cartimandua. Venutius replaced her as ruler of the Brigantes, and what happened to her after is unknown.

How Did Tacitus Shape Cartimandua’s Legacy?

As mentioned, much of what we know about Cartimandua comes from the writings of Tacitus. More broadly, much of what we know about Iron Age Celtic Britons comes from Roman writings, which were intended to characterize the Celts as barbarians on the periphery and to justify Roman imperial efforts to conquer the island of Britain. Therefore, Roman writings about the Celts, though useful, when the Celts left no written sources of their own, must always be taken with a grain of salt.

It seems evident from his writing that Tacitus maintained prejudices against women in power, and Cartimandua was no exception. The way that he wrote about her was impacted by such prejudices, and subsequently, her legacy has been shaped by them. Tacitus wrote that Cartimandua was lustful and was rejected as a ruler because of her gender. However, the archaeological evidence suggests that Celts had little issue with powerful women and that there were many throughout Celtic society. It also seems, from the written record, that Boudica was well-received by her people. If the Brigantes disliked Cartimandua, it was likely not because of her gender but because of her loyalties to Rome and her divorce from Venutius.

Tacitus also characterized Cartimandua as treacherous for her role in handing Caratacus over to Rome. While those Britons who were anti-Roman would absolutely agree, as discussed, Cartimandua clearly felt that it was more advantageous to be allied with Rome than to fight against them and saw it as a better solution for her people. Allying with conquered peoples was a part of Roman strategy, as they could use their land as an outpost. The people living there received benefits as a result. This was the case for Cartimandua when she sought aid during Venutius’s initial rebellion.

Though it seems odd that Tacitus would write about Cartimandua in such a negative way when she was clearly pro-Rome, or at the very least not anti-Rome, he was likely interested in undermining her role as a woman queen. Such a role went against Roman conventions and highlighted the barbaric “otherness” of Celtic Britain.

Bibliography

Green, M. (1995) The Celtic World, London: Routledge.