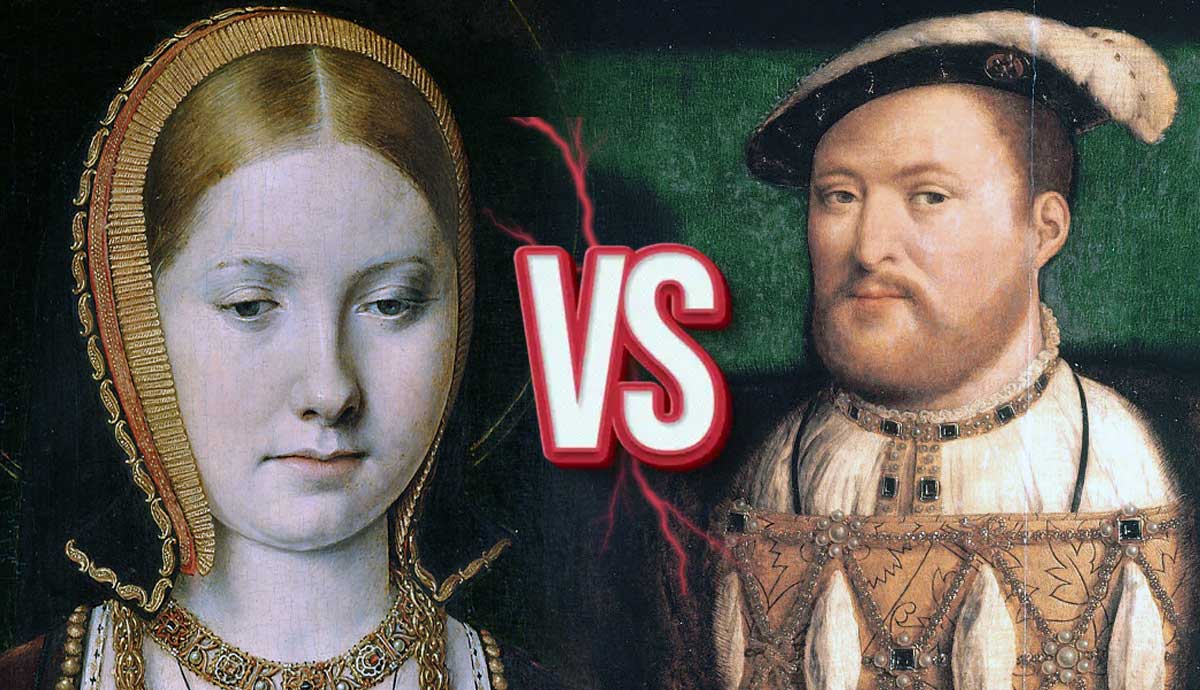

It is easy to overlook or forget, amid the notorious “divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived” rhyme and the glamorization of the Six Wives, that Catherine of Aragon was married to Henry VIII for longer than all his other wives put together. Lasting nearly 25 years, Henry and Catherine’s marriage was harmonious much of the time, with the king doting and relying upon his consort, who could easily have made a formidable ruler in her own right. What made Catherine a match for Henry—and where did it go wrong?

Catherine of Aragon Before Henry

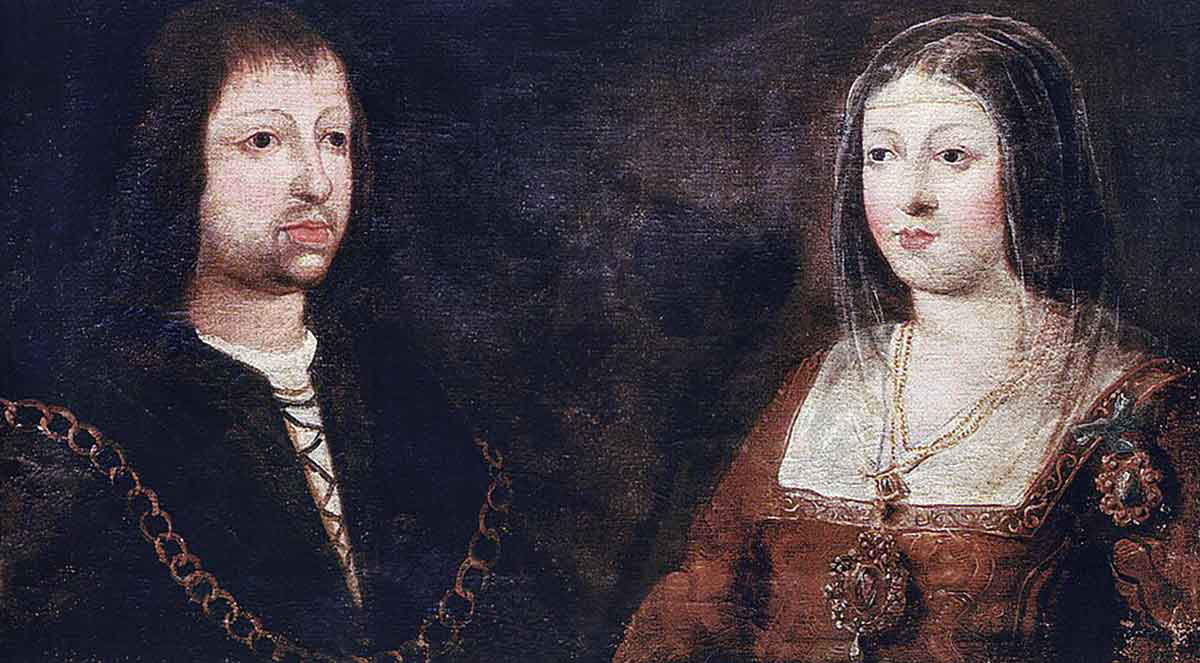

Born in 1485, Catherine’s patronymic (“of Aragon”) belies the importance of her parentage as a child of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. Ferdinand and Isabella, before the marriage, were heirs presumptive to the separate kingdoms of Aragon and Castile. Their union provided a de facto unification of the two kingdoms, which together accounted for the majority of the land on the Iberian peninsula and what would, some two centuries later, be called Spain.

Jointly, the couple oversaw a consolidation of Spanish territories, the promotion of Catholicism as the sole religion (including the expulsion of Muslims and Jews), and the beginnings of Spain’s colonial exploits across the Atlantic.

With this family background, Catherine unsurprisingly received the best education available. She was an eligible marriage prospect for members of other European dynasties looking to strengthen their alliance with the new, formidable power of a united Aragon and Castile. She was a particularly attractive option for Henry Tudor, or Henry VII of England, when in the late 1490s, he sought a match for his heir, Prince Arthur. Indeed, Catherine descended, on her mother’s side, from the House of Lancaster, which had ruled England intermittently for the last two centuries.

Henry VII’s accession to the throne, following the Battle of Bosworth, had ended the Wars of the Roses, in which the House of York had challenged the House of Lancaster, both claiming legitimacy via their common ancestor, John of Gaunt (son of Edward III and father of Henry IV).

Catherine of Aragon was also descended from John of Gaunt. Thus, a marriage between her and Arthur would provide the same kind of dynastic strengthening that Henry VII himself had achieved by marrying Elizabeth of York, making it harder for dissenters to challenge the Tudors’ claim to the throne.

Catherine and Arthur were married by proxy (meaning that the ceremony was performed in their absence, with stand-ins of marriageable age) in 1499 when both were 13 years old. They were married in person two years later when Catherine moved to England, where she would spend the rest of her life. Within less than a year, however, Arthur died of some form of plague or fever, and Catherine became a widow aged just 16.

Hers was not an ordinary widowhood but instead a time of political limbo. Catherine had brought a sizable dowry on her marriage to Arthur, only half of which Ferdinand had paid. Allowing her to return to Spain would have meant rescinding the claim to the other half and paying back the first half.

Always financially conscious, Henry VII was reluctant to let this happen, but by 1504, the advantages brought by Catherine’s parental connections to Aragon and Castile were reduced. Isabella of Castile died, and Catherine now provided merely a connection to the smaller, less prosperous kingdom of Aragon. Castile passed to Catherine’s older sister Juana, who was married to Philip, Duke of Burgundy—meaning a new set of alliance negotiations for Henry.

Keeping Catherine in somewhat restricted conditions in London, Henry VII allegedly pondered marrying her himself (his wife Elizabeth had died in 1503) but instead chose to betroth her to his younger son, the future Henry VIII. In this period, Catherine also acted as Spanish ambassador to England, corresponding with her father, Ferdinand, and meeting with Henry VII: her first taste of diplomacy and the first time a woman had acted as ambassador in Europe.

Catherine now faced a further trial: special dispensation from the Vatican would be required to allow the young Henry to marry his brother’s widow. Requiring papal dispensation was fairly common in royal families at this time. Catherine’s own parents had required dispensation to marry because, as second cousins, they were within the prohibited degrees of consanguinity. But Catherine’s case required her to make a testimony that would later become highly contentious. As she swore, her marriage to Arthur was never consummated and, therefore, could be considered not to have taken place.

Queen Catherine: Partnership, Patronage, and Politics

Catherine and Henry VIII were finally married shortly after he came to the throne in 1509 on the death of his father. They were crowned in a lavish ceremony that celebrated the heritage of both monarchs, proudly displaying their emblems: for Henry, the Tudor rose, which combined Lancaster white and York red; for Catherine, the pomegranate, a reminder of her Spanish roots and a symbol of fertility.

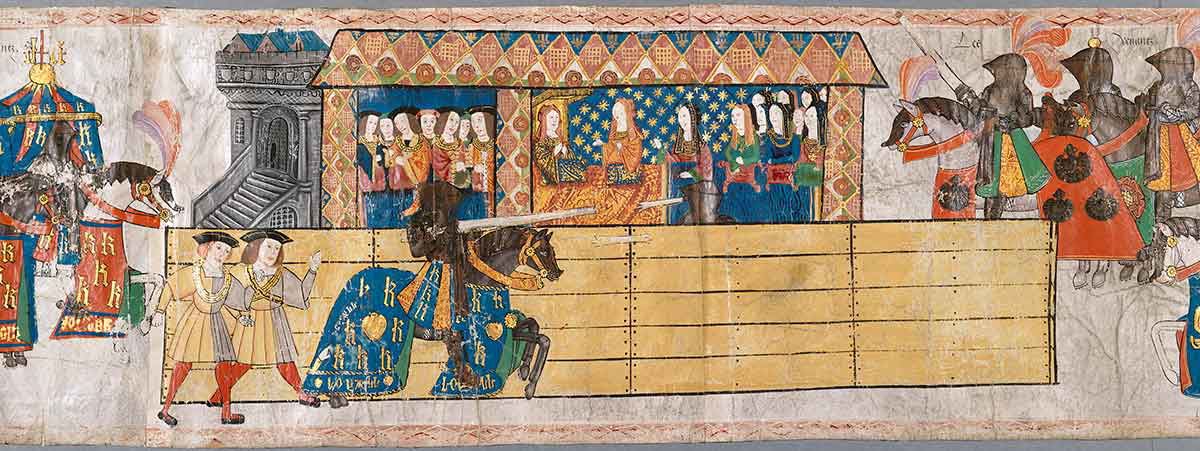

At the start of Henry VIII’s reign, ambassadors and chroniclers noted his possession of all the qualities befitting a Renaissance man: he was accomplished in several languages, a devoted scholar, especially of theology, and enjoyed poetry and music. He was also an avid jouster and rode in Catherine’s colors, with H&C on his armor and a pomegranate on his shield.

Although confined to the role of spectator at jousts, Catherine shared in Henry’s other pursuits as an intellectual equal. She, too, had had a thorough humanist education and was devoted to promoting education in her new role as queen consort. Scholars such as Erasmus and Thomas More found in her a willing patron, and in 1523, she commissioned Juan Luis Vives to write the treatise Education of a Christian Woman. Dedicated to Catherine, the text argued that women ought to be educated the same way as men because they were just as capable and the state as a whole would benefit from a fully educated populace.

These were radical ideas, especially since Vives advocated educating women regardless of their position in society. They presaged the emphasis placed on women’s education by Henry VIII’s sixth wife, Catherine Parr. Unlike Parr, though, Catherine of Aragon held these ideals within a Catholic framework. Parr might, for instance, have objected to Vives’s presentation of his egalitarian ideas entirely in Latin, which vast swathes of the population could not understand.

Education of a Christian Woman was principally written for Catherine and Henry’s daughter Mary, born in 1516. Mary was not their first child, but the first and only one to survive beyond just a few weeks. Beginning in 1510, Catherine had at least six pregnancies. Most were stillborn or miscarried. A son, born in 1511, was named Henry and celebrated as the longed-for heir, but he died suddenly a few weeks later.

There are many possible explanations for the fertility problems which became such an obsession for Henry. It is doubtful that the issues were solely on Catherine’s side because we know that Henry and his next wife, Anne Boleyn, had a similar series of miscarriages and stillbirths, also resulting in just one living daughter. Then again, Henry did have sons, not only with his third wife, Jane Seymour, but also with his mistress, Elizabeth Blount, in 1519. Henry Fitzroy (the surname means “son of the king”) was openly recognized by Henry and accepted at court, though he could not be officially made the heir. He died in 1536.

Catherine’s response to Henry’s infidelities is, perhaps unsurprisingly, not recorded. Only when things became more extreme—when he began to talk of putting her aside in favor of Anne Boleyn—was she obliged to react.

Before this, though, there were few signs of any obstacles in Catherine and Henry’s relationship, even despite their difficulty in producing an heir. Henry continued to value her highly, leaning on her more than many prior monarchs had leaned on their consorts. Perhaps inspired by the marriage of equals of her parents, Catherine actively supported Henry in a political capacity.

Most famously, she organized troops to send to Scotland in 1513 while Henry was away fighting another military campaign in France. Having gathered an army, she rode under the royal banner to address them with a rousing speech. The English troops went on to defeat the Scots at the Battle of Flodden, at which the Scottish king himself, James IV, was killed.

Reporting the news to Henry in France, Catherine enclosed a piece of James’s bloodied coat to use as a banner. It was perhaps this aptitude for the art of war that made Thomas Cromwell, later Henry’s most prominent minister, reportedly say of Catherine: “if not for her sex, she could have defied all the heroes of History.”

Queen Catherine’s Portraits Decoded

Like many people in positions of power throughout the ages, Catherine used portraiture to advance a chosen image of herself. Catherine’s portraits are particularly interesting for the insights they give into how she viewed her marriage with Henry, as it evolved over two decades and eventually soured.

Naturally, Catherine is always pictured in clothes and jewelry indicative of her status as one of the richest women in Europe. But there were occasional touches of symbolism, too: a portrait thought to be an eleven-year-old Catherine shows her holding a Lancaster rose, indicating the dynastic path she was soon to follow.

A portrait from 1520 shows the queen in a rich red gown with gold sleeves patterned with pomegranates. This symbol, which also appeared on royal buildings (and can still be seen on a doorway at Hampton Court), connotes Catherine’s devotion to her marriage and her hopes for fertility, in spite of the numerous problems she and Henry had had by this time.

Another symbol Catherine used, and a more surprising one, was a monkey. Traditionally, monkeys in art could stand for mischief, evil spirits, and even the Devil. In a miniature from 1525, around the time Henry was beginning proceedings to annul his marriage to Catherine, she is pictured holding a monkey, which holds a rose in one hand and grasps, with the other, a crucifix hanging from Catherine’s dress.

The monkey itself is probably present simply because it was a fairly common pet for people of high status and possibly a reminder of Catherine’s native Spain. However, its positioning is the most important part of the portrait. Clutching a rose signifies unswerving loyalty to the Tudor dynasty, and pointing at the crucifix underlines devotion to faith. As what would become known as “The King’s Great Matter” unfurled, Catherine was determined to uphold these two qualities: steadfast loyalty to Henry and her role as his wife and a pious devotion to God’s will.

The King’s Great Matter

Having joined the royal court as one of Catherine’s ladies-in-waiting in 1522, Anne Boleyn was by 1525 the object of a protracted and persistent pursuit by Henry—protracted mostly because Anne would not settle for being his mistress, but sought to become his wife. She may well have encouraged Henry’s belief that his marriage to Catherine was unlawful in the eyes of God and that this was why it had not led to a male heir.

In religious terms, Henry’s case for annulling his marriage to Catherine was based on the fact that she had been married to his brother Arthur first. Consulting the Old Testament, he found in Leviticus, chapter 20, verse 21: “If a man takes his brother’s wife, it is impurity. He has uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless.”

Those who opposed the annulment, which included not just Catholic supporters such as Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher but also the Protestant monk Martin Luther, could have pointed to a contradictory passage from chapter 25 of Deuteronomy, verse 5, which actually obliges a man to marry his brother’s widow if their marriage has been childless.

In political terms, various factors complicated “The King’s Great Matter.” In 1527, Henry’s minister, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, convened an ecclesiastical court. The hearing would give Henry the opportunity to explain his conviction that he had married Catherine unlawfully, Catherine the opportunity to maintain that she and Arthur had not consummated their marriage, and theological and legal experts, including a papal legate, the opportunity to offer their opinions.

But events outside England overshadowed these proceedings. Also, in 1527, Rome was sacked by forces belonging to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, who happened to be Catherine of Aragon’s nephew. Charles had acceded to the title in 1519, gaining the vast territories of the Holy Roman Empire, which included swathes of Germany, the Low Countries, Austria, and Italy. He also, as the son of Catherine’s sister Juana, ruled most of Spain.

The Sack of Rome in 1527 forced the pope, Clement VII, into captivity in the city’s Castel Sant’Angelo. Practically, it was now difficult for envoys from England to gain access to the pope to consult on Henry’s case. In terms of international relations, it was highly unlikely that the pope was going to allow Henry to annul his marriage to the aunt of the immensely powerful ruler who currently held him prisoner.

By the early 1530s, Henry could endure the stalemate no longer and began to believe that, as a divinely ordained monarch, he should not be impeded by papal authority. He took steps towards proclaiming himself the head of the Church of England and obtaining a divorce from Catherine, banishing her from court in 1531.

In late 1532 or early 1533, Henry privately married Anne Boleyn. Supporters of Catherine, such as More and Fisher, grew even more dissenting when Henry’s Act of Succession in 1534 required them to repudiate Henry’s marriage to Catherine, invalidate Mary’s claim to the throne, recognize Henry’s marriage to Anne, and confirm that the pope had no authority in England. When More and Fisher refused to sign, they were imprisoned and executed for treason.

All this time, Catherine, despite her powerful supporters, had no political sway of her own. There was little she could do other than write to these supporters, including her nephew Charles V, describing Henry’s poor treatment of her and affirming her continued belief that she was his wife, legally and morally. It was reported that Catherine, throughout Henry’s flirtation with Anne and the gradual institution of Anne as the new queen, continued to make and embroider Henry’s shirts.

Catherine of Aragon After Henry VIII

Catherine had been a key figure in the series of events precipitating the English Reformation. But after she was banished from court and Henry married Anne, Catherine resolutely continued to follow her Catholic faith and was now completely sidelined. Whereas Anne of Cleves, Henry’s other “divorced” wife, would, the following decade, live in prosperity after the marriage ended, gaining the honor of being treated as the king’s sister, Catherine of Aragon was only granted the right to the title “Dowager Princess of Wales” (as the widow of Arthur, former Prince of Wales).

The remainder of Catherine’s life was peripatetic: she was transferred around a series of royal castles, mostly in the Home Counties around London. She had rejected the idea of entering a convent (as some consorts, such as Elizabeth Woodville, did following the death of the king) because she maintained that she still had a husband living and had sworn before God to uphold her duty to him. Her life at these castles, though, was not dissimilar to convent life. By the time she was living at Kimbolton Castle (Cambridgeshire) in 1534, she lived a life of prayer and fasting, confining herself to one room except to attend Mass.

She was not permitted to see her daughter, Mary, communicating with her by secret letters. She also communicated with her nephew, Emperor Charles V, asking him to protect Mary after she died. This was, it turned out, not long coming. In January 1536, she died at Kimbolton aged 50, possibly from cancer. In a curious and dark turn of events, Anne Boleyn miscarried on the day of Catherine’s funeral: a child who would have been the long-desired male heir. Neither she, Henry, nor Mary attended the funeral at Peterborough Cathedral.

At the time, Catherine’s supporters celebrated her as a paragon of wifely devotion and piety, lamenting she had been one of the first victims of Henry’s ruthlessness as he pursued a break with Rome at all costs. Quite understandably, this aspect of Catherine’s legacy has overshadowed all that she achieved and stood for as queen before, around 1525, when there was no sign that Henry would take a second wife, let alone six in total.

Her role in shaping England immediately prior to the Reformation was significant, matching the young Henry VIII’s humanist and Renaissance values, as well as his aims on the battlefield and in diplomacy. Her refusal to give in to Henry’s will and cooperate with the annulment proceedings had an even more significant impact on English history, albeit one unintended by her: leading to the Reformation and a legacy of religious uncertainty throughout the Tudor period and beyond.