Like real-life Red Sparrows, Cold War female spies danced across the male-dominated stage of espionage to their spymasters’ tune. From courting Einstein to killing Hitler, discover the dangerous missions and treacherous twists and turns that these women’s double lives took when they accepted the Kremlin’s call to fight a psychological war in the shadows.

1. Red Nightingale: Nadezhda Plevitskaya

Singer. Actress. Spy.

Imperial audiences greeted Nadezhda Plevitskaya’s appearances with standing ovations. So, how did Nicholas II’s favorite folk singer end up on trial in a French court as a Soviet spy?

Born in Kursk to a family of twelve children, Nadezhda Plevitskaya (1884-1940) started life as a peasant girl with a voice like a nightingale. She soon enchanted audiences in Moscow and Kyiv. By 1909, she performed in high society salons and for Tsar Nicholas II. Her repertoire of folk songs appealed to aristocrats and workers, turning her into a popular icon. Before long, Nadezhda only entertained the elite, as ticket prices for her concerts were out of reach for the masses.

Before political events thrust her into the whirlwind of revolution, Nadezhda had already conquered hearts, giving 40 music tours in Russia, Western Europe, and America. With her new wealth, the singer bought luxury apartments and supported numerous charities.

Married four times, first to a Polish dance master, then to two Russian officers, and finally to a White Army general, Nadezhda led a tumultuous life ruled by music, money, and love. When World War I engulfed Europe, Nadezhda followed her husband, Lieutenant Vladimir Shangin, to the front, where she joined the Red Cross. Five months later, tragedy struck when Shangin died on the battlefield. When the Bolshevik Revolution came, Nadezhda started singing for the Red Army. She also remarried, this time to Lieutenant Yuri Levitsky, an officer mobilized into the Red Army during the Soviet occupation of Kursk.

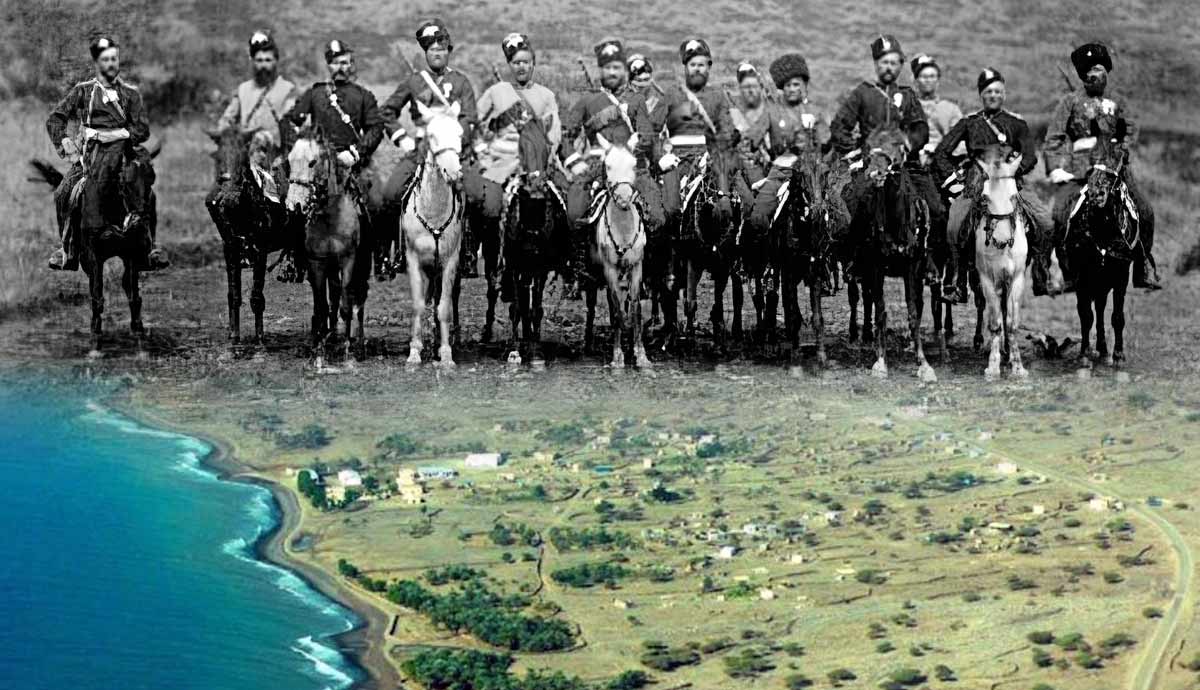

In 1919, she switched sides when she was captured with her new husband by the White Army. There, she fell in love again, this time with handsome, emaciated Nikolai Skoblin, an aristocratic cavalry officer eight years her junior and the youngest general in the White Army. Ignoring their political differences, a smitten Nikolai saved Nadezhda from the firing squad. After a secret engagement, an escape from Russia, and time spent nursing Skoblin back to health, the singer married the general in exile.

Despite popular music tours in Paris and New York in the early 1920s, Plevitskaya struggled to adapt to life outside of her homeland. When the initial “Russian craze” plummeted, so did her finances. In France, the former Red Army darling pursued her singing career as well as a taste for jewelry and furs, which neither she nor her husband, a Russian All-Military Union (ROVS) intelligence chief, could afford.

Founded by Baron Pyotr Wrangel, ROVS functioned as a support system for émigré soldiers. It also fomented anti-Soviet uprisings in Russia. Soviet intelligence services kept a close eye on the organization, which boasted 20,000 members, fearing that if war broke out in Europe, the anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army would join forces with Germany.

In 1930, a homesick Skoblin and Plevitskaya petitioned the Soviets for amnesty to enable them to return to their country.

The Soviets saw their chance. In return for restored civil rights, a country-wide tour for Nadezhda and a position on the Red Army General Staff for Nikolai, Soviet intelligence recruited the couple into their ranks. For the next seven years, they spied on their friends, reporting ROVS’ every move to the Soviets. Under the code names “Farmer” and “Farmer’s Wife,” they helped neutralize 17 anti-Soviet agents smuggled into Russia and demolish 11 safe houses in Leningrad, Moscow, and the Transcaucasia region.

In 1937, the NKVD (Soviet secret police) hatched a plot to kidnap the head of ROVS, General Yevgeny Miller. The plan would only work if Skoblin lured Miller into a trap. Miller had previously appointed Skoblin head of the “Inner Line,” a secret intelligence sector within ROVS that focused on targeting the Bolsheviks. In this role, Skoblin accessed key information about internal sabotage operations.

By 1936, General Miller removed Skoblin from his leadership role. Skoblin and several other officers then declared open war on Miller. Tense relations between the two men escalated from a power struggle to betrayal. Although he remained in the dark about Skoblin’s Moscow handlers, the general began to suspect a conspiracy.

On September 22, 1937, Miller left his office at 12:30 p.m. to attend a lunchtime meeting that Skoblin arranged between two officers from the German embassy in Paris. These officers wanted to harvest intelligence from ROVS to use against the Soviets. They encouraged ROVS to join forces with Hitler to beat the Soviet Union. Unbeknownst to Skoblin, the general, suspecting a trap, left a note behind as a safeguard. This note played a key role in the subsequent high-profile trial. After arriving at the rendezvous point at the corner of Rue Jasmin and Rue Raffa, Miller stepped into Skoblin’s car and disappeared.

Skoblin drove Miller to a villa rented by the NKVD on the outskirts of Paris. Then Skoblin left the general with the two alleged German officers. Inside the villa, the officers suddenly revealed themselves as NKVD agents. Overpowering Miller, they drugged him with sedatives and stuffed him into a wooden shipping container punched with air holes to keep him alive.

The Soviets smuggled Miller onto a cargo ship, the Marya Ulyanova, which sailed from the French port of Le Havre to the USSR via the Baltic. When Miller did not return from the meeting, his secretary discovered the note. Instead of calling the police, two ROVS generals went to confront Skoblin. Skoblin claimed he did not see Miller that day. While the generals discussed how to handle the situation, Skoblin exited the office and vanished.

Meanwhile, NKVD agents took Miller to Moscow, where they interrogated him for two years before his execution. Meanwhile, the Soviets spirited Skoblin to Spain, where they killed the general and tossed his body out of an airplane during an air raid over Barcelona.

Despite her claims that the Soviets also kidnapped Nikolai, Nadezhda was arrested and sentenced to 20 years of penal labor. The folk singer died in prison two years later, during the Nazi occupation of France. According to one story, NKVD agents poisoned Plevitskaya in her cell, while another version claimed that the Nazis eliminated her as a suspected Soviet spy. One thing remains clear: both the Germans and the Soviets believed that Nadezhda knew too much. After Nadezhda’s death, the Nazis exhumed her body, possibly to verify her identity, and then reburied her in a common grave.

Today, the full story of Nadezhda and Nikolai’s role as Russian spies remains sealed inside the archives of the Russian Federation.

2. Fraternizing With Hitler: Olga Chekhova

It’s a provocative picture. A beautiful blonde movie star smiling next to one of the most brutal dictators of the twentieth century.

Born into a Russianized German family in 1897, Olga Knipper, the niece and namesake of Anton Chekhov’s wife, would later hit English tabloid headlines as “the spy who vamped Hitler.”

In 1920, Olga escaped war-torn Russia while smuggling out a single diamond ring. Her brother Lev, who had opposed Bolsheviks during the Civil War, returned to work as a composer and a possibly reluctant Soviet spy. His previous service for the White Army marked him for death if he failed to cooperate with the new regime.

Meanwhile, Olga found her way into the German movie industry, making a name for herself in the 1930s as the favorite film star of dictator Adolf Hitler. Under this glamorous cover, the actress also allegedly worked for Soviet intelligence. Recruited by her brother, Olga memorized secret codes, learned encryption techniques, and mapped safe houses while preparing to go deep into the ranks of the Third Reich.

After dazzling Hollywood in a Hitchcock film, Olga starred in 150 films and played erotic roles in Berlin’s postwar theaters. No wonder she became the Führer’s favorite by 1933, the year that Hitler was appointed German chancellor. After Hitler met Olga, he showered her with notes and presents. Hitler wasn’t the only one smitten with the woman he soon dubbed the state actress of the Third Reich. German soldiers and airmen also tacked up Olga’s photo in their quarters and throughout the Luftwaffe barracks.

As Europe headed towards war, Olga reveled as a Nazi socialite, cozying up to Hitler, Göring, and Goebbels. During her double life, she rubbed elbows with the Führer at diplomatic receptions. She slept with Nazi flying aces, danced on the table at a Third Reich New Year’s Eve party, and even became friends with Hitler’s mistress, Eva Braun. Embedded in the Nazi hierarchy, this Soviet asset became a part of the Nazi propaganda machine. Her proximity eventually placed her at the center of a Soviet intelligence plan to assassinate Hitler.

Although Olga posed for photographs with Hitler, it is unknown whether she discussed secret state matters with him. What is known is that she warned Goebbels in 1941, in a show of undisguised patriotism, that Germany would never defeat Russia.

Whether a Soviet agent or a wartime opportunist, Olga lived a charmed life, fêted by the Third Reich, while juggling a relationship with Viktor Abkumov, the brutal director of the Soviet counterintelligence agency, SMERSH. In April 1945, Olga escaped to a secret retreat in the forests outside Berlin as the Red Army marched on the city. One day, Soviet soldiers burst through the door of her house. An enemy actress alone in hostile territory could have spelled disaster. But when Olga began speaking Russian, the situation changed fast. A senior officer, called to the scene, recognized her famous surname, and contacted the NKVD.

The NKVD airlifted Olga to Moscow for debriefing as the Nazi regime collapsed. For two months, she stayed in a covert apartment, guarded by Soviet officers who drove her to the Kremlin for secret meetings. When Chekhova moved to West Germany after the war, the Soviets rewarded her with a comfortable lifestyle.

Driven by ideology, fear, or the complex loyalties of a totalitarian age, Olga’s role as a Kremlin spy within the Third Reich remains a legendary tale of opportunism that adds an intriguing footnote to the history of World War II.

3. Spying for Stalin: Elena Ferrari

Being a Russian spy meant navigating changing political winds, and not everyone who spied for the Cold War bugbear made it out alive.

Born Olga Fedorovna Revzina to a family of Jewish origins, Elena Konstantinovna Ferrari (1899-1938) became a career spy for the Red Army. As a teenager, Elena spoke fluent English, German, French, Italian, and Turkish. In 1916, she joined the Bolshevik Party before defecting to the anarchists during the Russian Civil War. By 1918, she changed allegiance and joined the Red Army. During a fierce battle in Ukraine, she lost a finger on one hand, which gave her a distinctive appearance.

When the war ended in 1920, she trained as a spy at the future GRU academy in Moscow. After her graduation, Ferrari participated in an assassination attempt against General Pyotr Wrangel. In October 1921, she and other agents steered the Italian steamship Adria into the general’s yacht, Lukullus, moored at Constantinople. The boat sank within minutes, along with three sailors, the White Army’s records, and a treasury of 40,000 francs.

Before the crash occurred, Wrangel and his family went ashore, enabling them to escape the assassination attempt. When Turkish authorities seized the Adria, they could not prove that the Soviets caused the disaster. Witnesses, however, claimed to spot a dark-haired woman with four fingers, later identified as Ferrari, aboard the Adria when it rammed into Wrangel’s yacht.

In 1922, Elena showed up in Germany, sporting a new surname, Ferrari. Painting herself as a refugee, she insinuated herself into émigré literary circles that included novelist Maxim Gorky and other important figures of 1920s Russian Berlin. Behind the scenes, however, Ferrari worked to dismantle anti-Soviet activities in Berlin.

Disaster struck in 1923 when Gorky discovered her Soviet connections and warned the others that Ferrari worked for the Bolsheviks. With her identity exposed, Elena returned to Moscow and initiated a new intelligence operation in Italy. Once again, she ingratiated herself into the émigré community and even published a collection of poems.

Next, Elena began undercover work in the United States. Under the code name “Vera,” Elena arrived in New York City to recruit new American agents. As a cover, she joined a local art studio and cozied her way into circles where prominent government officials ran. Her success brought more accolades, including the Order of the Red Banner award.

Just before her next mission, Ferrari’s ascent took a sudden nosedive. The Great Terror, which began devouring Communists once in favor with the regime, caught up to her. In December 1937, the Soviets charged Elena with treason for counterrevolutionary espionage. The Supreme Court sentenced its former spy to death on June 16, 1938. Elena Ferrari was executed by firing squad at the Kommunarka training ground outside Moscow on the same day as her arrest.

4. From Russia, With Love: Margarita Konenkova

When famous theoretical physicist Albert Einstein exchanged a flurry of intimate letters with a married socialite during the 1940s, he had no idea that he had just fallen in love with an alleged Soviet spy. Einstein first met Margarita Konenkova (code name “Lukas”) at Princeton during World War II. Among the circle of American scientists there, the two developed a close relationship. She was 51, and Einstein was 56.

The letters that Einstein wrote to Margarita reveal a poetic side to the famous scientist. The couple exchanged multiple letters, nine of which survive today. What Einstein didn’t know was that the woman who loved him was a Russian agent tasked with influencing American scientists. Despite frosty relations between the Soviet Union and the United States, Konenkova introduced Einstein to Pavel Mikhailov, the Soviet consul and a Soviet military intelligence officer, and facilitated multiple meetings. After meeting in 1935, the couple spent several months together at Einstein’s home in Lake Saranac, New York. “Everything here reminds me of you,” Einstein later wrote Margarita from his Princeton home during the first postwar winter.

Despite Konenkova’s occupation and Einstein’s infatuation, no evidence exists that he passed classified information on to her. What is known is that she had relationships with important scientists such as Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb.

By 1945, Margarita returned to Russia. But distance didn’t stop their romance. Albert and Margarita kept their relationship secret the entire time. In 1994, a Russian newspaper exposed the affair. Former Soviet spymaster Pavel Sudoplatov backed up the claim that the Kremlin tasked Konenkova with pressuring Einstein for nuclear intelligence, although he had no direct link to the Manhattan Project. When Konenkova returned to Moscow in 1945, the state provided for her, suggesting that Stalin found her work in America useful.

While Einstein dropped no bombshell secrets, the letters provide an intriguing view into the lives of two people who found sanctuary in each other. Until the archives reveal the truth, whether Margarita had real feelings for Einstein or only viewed the scientist as a source of information remains a mystery.

5. The Housewife Who Almost Killed Hitler: Ursula Kuczynski

Planting a Soviet sleeper agent right under the noses of the British authorities became something of a scandal during the Cold War.

Spy, mother, and woman of many aliases, Ursula Kuczynski (1907-2000), born in Berlin to a left-wing Polish-Jewish family, became one of those deep-cover agents that the West feared.

Operating for over a decade, Ursula became a successful author, served as a colonel in the Red Army, and evaded suspicion as a Soviet operative-–all while raising three children. In the 1930s, her progressive politics led her into active espionage for the USSR. When Ursula moved to China, she was recruited by Richard Sorge, the Soviet spymaster in the Far East. Next, Ursula gained her spy bona fides at the GRU school outside Moscow. There, she learned Russian and Morse code while building radio transmitters and receivers designed to transmit information to her handlers. Afterward, the GRU deployed Ursula to operate spy rings in Britain, Poland, Switzerland, and China.

On the eve of the Second World War, the Soviets deployed Kuczynski to the German-occupied city of Danzig. Hot on a new spy ring mission, Ursula met an English Communist named Len Beurton there. In 1940, the GRU authorized Len and Ursula, who already had a husband, to marry. This act gave Ursula British citizenship, enabling her to work as a spy in England. A wave of clandestine transmissions followed, as she recruited multiple high-level agents including Klaus Fuchs, a German political exile, who worked in a secret atomic research facility near Harwell.

During World War II, Ursula sent Moscow important atomic bomb data, obtained from several nuclear physicists via radio transmissions. She often bicycled into the countryside to meet Fuchs, where he provided her with secret documents written in tiny script.

Time after time, Ursula escaped detection, even though counterintelligence operatives almost caught her several times. The Oxfordshire housewife even came close to helping assassinate Adolf Hitler. In 1939, the Soviets hatched a plot to kill Hitler as he ate dinner in a private dining room at one of his favorite restaurants, the Osteria Bavaria, in Munich. After scoping out the security guards, Len and his accomplices planted a bomb in a suitcase next to a wall partitioning the main restaurant from the dictator’s private dining space.

Right before springing the plot, Stalin, who had just signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, called off the operation. Stalin believed that with Hitler dead, the surviving German generals would join Britain and the United States in an anti-Soviet alliance.

After World War II, Kuczynski’s spy work ended without explanation. Moving to East Berlin, Ursula escaped detection and worked as a popular children’s author under the name Ruth Werner until her death at 93. Thanks to her mundane disguise as an apron-wearing, cake-baking housewife who took long bicycle rides in the countryside, Ursula Kuczynski became one of the 20th century’s most successful spies.