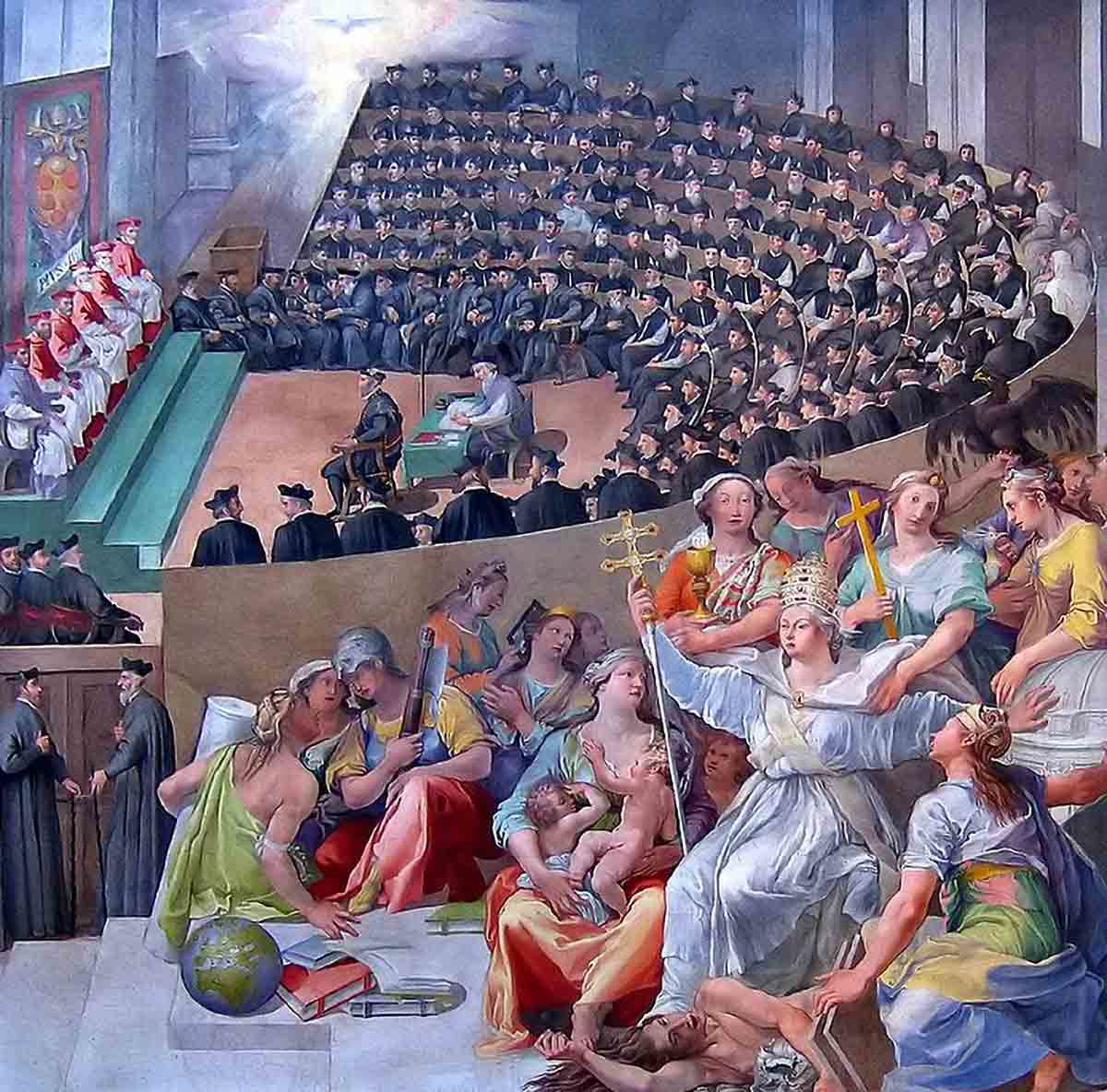

The Council of Trent (1545-63) was one of the most important parts of the Counter-Reformation movement. It was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, and was largely prompted by the Protestant Reformation. Held in Trento, Italy, it was also the last time that such a council was held outside of Rome, the home of the Catholic Church. In this article, we will explore the details of the council and the impact that it had on European society at the time, and since.

Background to the Council of Trent

Despite the first meeting not being held until 1545, the background to the council itself can be traced as far back as 1517, when Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Church in Wittenberg, calling for reform of the Catholic Church and ultimately sparking the Protestant movement.

In 1520, Luther himself appealed to the German princes to oppose the papal church through the form of a council in Germany, free of the Papacy. After Pope Leo X had issued a papal bull condemning 52 of Luther’s 95 theses as heretical, the princes somewhat agreed with Luther in thinking that a council might be the best way to restore good relations between the Papacy and the German states. Similarly, German Catholics also hoped for a council to rectify their issues.

It would take another 25 years for a council to materialize, but there were valid reasons for this. Geopolitical, religious, socio-economic, and cultural problems in Europe all seemed to merge together in the early to mid-16th century. King Henry VIII had been excommunicated and had gone on to form the Church of England, turning one of the Catholic Church’s biggest supporters anti-Pope. It was also not received well in England, where many latched onto Catholicism, only to see their beloved monasteries stripped in the 1530s by Henry’s men.

Moreover, King Francis I of France and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, were at each other’s throats, while the threat from Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent from the Ottoman Empire was creeping ever closer to Central Europe.

In 1527, a new sack of Rome had taken place, with Charles V’s mutinous troops (many of whom identified as Lutherans) attacking Rome, pillaging and raping as they went and even going as far as to use St Peter’s Basilica and the Sistine Chapel for stabling their horses.

Interestingly, Charles V actually favored a council, but to do so, he needed the support of Francis I, with whom he was at war. Francis, on the other hand, was not too keen on a council, partly because it meant supporting his main military rival, Charles, but also because he actually partially supported the Protestant cause in France.

Interestingly, it was actually Charles V’s younger brother, Ferdinand of Austria, who would get the ball rolling with the Council. In 1532, Ferdinand, who ruled a huge amount of territory in Central Europe, agreed to grant religious liberty to Protestants as part of the Nuremberg Religious Peace. This was followed a year later by Ferdinand suggesting that a general council should include both Catholic and Protestant European rulers to come to a theological compromise between the two belief systems.

Naturally, the Pope at the time (Pope Clement VII) opposed this because it meant acknowledging that the European rulers were more powerful and held more sway than the Pope himself, while also acknowledging that Protestantism was a belief system worth debating. Eventually, the Council would take place, and its first session began in 1545.

The Early Council Organization

Following Pope Clement VII’s death in 1534, a new Pope was elected: Pope Paul III. Paul would be the Pope to open the Council formally, although when he suggested the idea to his cardinals, it was vehemently opposed.

By 1537, Paul had acknowledged what Clement could not bear to—that Protestantism was not just a passing phase, or a cult followed by random outcrops of European groups, but a full-blown religion in its own right. He issued a decree for the council to be held the very same year.

Similarly, Martin Luther wrote the Smalcald Articles in preparation for the Council, outlining what Lutherans could and could not compromise on. The Council was agreed to commence in Mantua, Italy, on May 23, 1537.

However, another war broke out between Charles V and France. As such, the French prelates refused to attend, as did many Protestants. The Council was instead moved to Vicenza, before being completely postponed on May 21, 1539, due to poor attendance.

In the meantime, Pope Paul III began to look at internal Church reforms, while Charles V made peace with Protestants and Catholics alike at the Diet of Regensburg in 1541.

The First Sessions (1545-49)

The Council ended up taking place in 1545, just a year before Martin Luther’s death. During the Council sessions, none of the three Popes who reigned (Paul III, Julius III, and Pius IV) ever attended any of the sessions, instead being represented by papal legates, as requested by Charles V.

Despite proposing that the Council meet at Mantua, it eventually met at Trent instead, which was interestingly under the control of the Holy Roman Empire at the time. Pope Paul III wanted to move the Council to Bologna in 1547 to avoid a bout of plague, but this never materialized. The Council was eventually prorogued on September 17, 1549.

The Second Sessions (1551-52)

The Council reopened in Trent on May 1, 1551, by the convocation of Pope Julius III. It was closed just under a year later (April 28, 1552) after a surprise victory by Maurice, Elector of Saxony, against Charles V, who had marched into the state of Tyrol.

The reason that the third session did not open for another decade was that the very anti-Protestant Pope Paul IV had been elected, and there was no chance of him acknowledging that such a council should even exist.

The Third Session (1562-63)

By the time the third (and final) session came around, there was no hope of conciliating the Protestants. In the meantime, the Jesuits had become a major force to be reckoned with, particularly in the New World, where they were competing with Catholic missionaries in the Caribbean.

Pope Pius IV opened the Council on January 18, 1562, for the final time and closed on December 4, 1563. It was in this final session that arguably the most important work was undertaken. Some sort of conclusion was reached (which will be discussed later), as the Council closed with acclamations for the reigning Pope, the emperors and kings who had supported it, cardinals, ambassadors, papal legates, and those who had attended and contributed.

Interestingly, the French monarchy had boycotted the entire Council until November 1562, which was shortly after the French Wars of Religion had broken out. During these Wars of Religion, the French Church experienced iconoclastic violence from a strong and significant Protestant minority. This had not been an issue in other European churches, particularly in Spain and Italy, so it was the French who added the last-minute decree on the protection of sacred images.

What Did the Council of Trent Achieve?

Firstly, the objectives of the Council need to be looked at. There were two primary objectives. The first one was to condemn the principles and doctrine of Protestantism and to clarify the doctrine of the Catholic Church on all disputed points. The second objective was to effect a reformation (or rather, a Counter-Reformation) in discipline or administration.

For the first objective, Charles V had expected Protestants to be given fair input at the Council, and he secured an invitation for the Protestants to be present and to be protected during the Council during the Second Session in 1551-52.

However, upon their arrival, the Protestants were not given a vote. Some had not even found out that they had been invited until 1552, and never even reached Trent. This refusal, combined with Maurice, Elector of Saxony’s victory against Charles V in the same year, effectively put an end to any form of Protestant cooperation, as many realized the Council was just a farce from their perspective.

As for the second objective, one of the main thought processes behind how the European and English Protestant Reformations started was due to the seemingly obvious corruption in the administration of the Catholic Church in the early 16th century.

When looking at its own corruption, many Catholic Church senior members refused to acknowledge that this was a problem. A remarkable 25 public sessions were held, but most were spent simply going through formalities, achieving nothing.

While some abuses were brought up and abolished, absolutely no concession at all was made to Protestantism.

Legacy and Conclusions

While the initial objectives may not have been met from a Protestant perspective, it is important to look at the broader picture when analyzing the Council of Trent. The fact that this council lasted for almost 20 years across three distinct sessions is enough to prove that it certainly had a lasting legacy.

In fact, the Council of Trent ultimately helped to shape the future of the Catholic Church for the next 400 years. The Council helped to solidify Catholic doctrine at the height of the Protestant Reformation, which was gripping Europe in its vices at the time.

Furthermore, the fact that the Wars of Religion had erupted in Europe over Catholicism vs Protestantism—something which would dominate the 17th century during the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48) also goes to show how serious and much-needed the Council was.

The Council was also a good move at the time from both a political and religious point of view. Had the abuses in the Catholic Church not been addressed at the time, Protestantism would undoubtedly have taken over the entire continent as the dominant religious force, and the fact that the Catholic Church recognized these abuses goes to show that the Council was indeed necessary at the time.

Overall, the Council of Trent helped to shape the future of the Catholic Church and, for better or for worse, kick-started the Counter-Reformation in Europe, which would dominate the continent for the next 200 years.