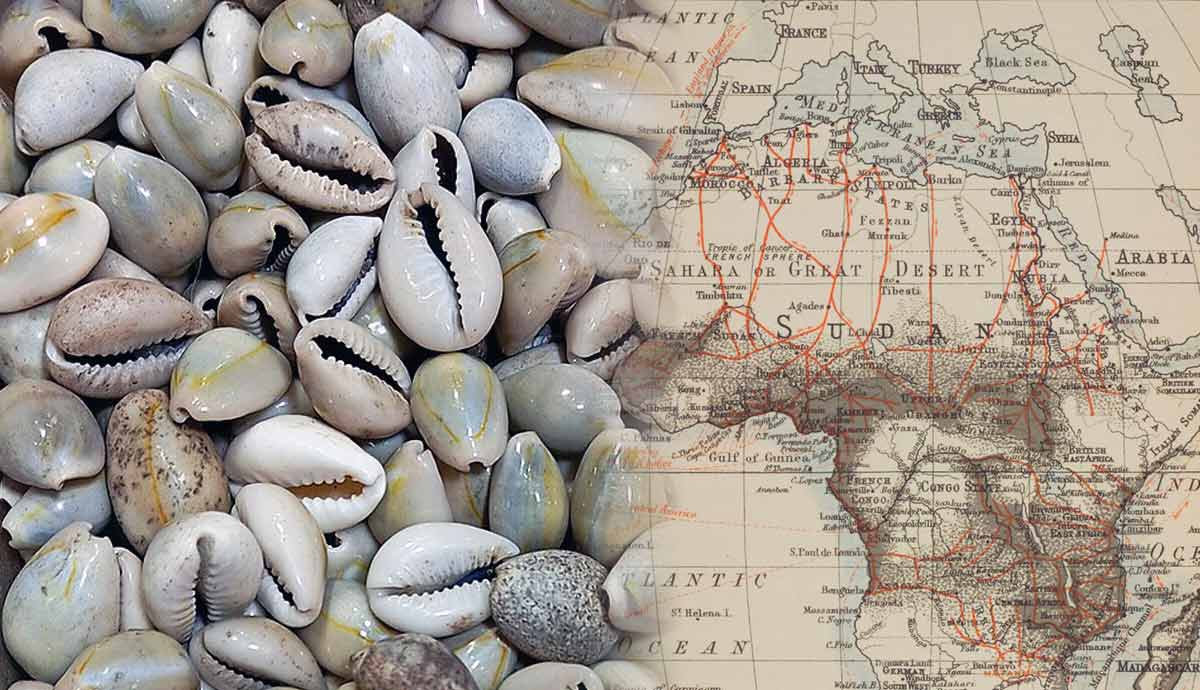

There are over 250 different species of cowrie shells around the globe. However, two species in particular became woven into various Asian and African societies both as a form of currency and an object with ceremonial, cultural, and ritualistic significance. From the 17th century, cowries, gold, and tobacco became entwined in the Atlantic, playing an integral role in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. In North America, cowries even found a place within the 17th and 18th century fur trade. From the beaches of the Maldives, cowries transformed into a cornerstone of the modern world.

Monetaria Moneta: The ‘Money Cowrie’

Cowries can be found in the waters of Central Mexico, coastal East Africa, and areas of South and Southeast Asia. However, one species of cowrie in particular gained significance as a form of currency to the extent its Latin name, monetaria moneta, literally translates to ‘money cowrie.’ It is found only in the Maldives, an archipelago (island group) off the coast of present-day Sri Lanka. It is here that the cowrie snail plays a role in the underwater ecosystem, eating algae to maintain the health of surrounding coral reefs and other habitats.

Above water, however, cowries came to be valued for their visual appearance. Their milky-smooth surfaces have been likened to porcelain and vice versa. In fact, the word porcelain comes from the word porcellana—during Marco Polo’s travels to China in the 13th century, he came across cowrie shells in various parts of Asia, particularly in trade settings. To him, the rounded backs of the shells bore similarities to a porcellus, or piglet. It is no wonder that Marco Polo saw similarities between porcelain and cowrie shells, as both had a polished glow and snow white surfaces.

Extracting the Cowrie

According to various Arab, Portuguese, British, and Dutch sources, cowries were extracted using several methods. Cowries washed up on shore were considered low quality. This was due to surface weathering after being continuously rolled on the beach, causing them to lose their shine and luster. The small animal inside needed to be living in order for cowrie shells to be of any value. Cowries were also mainly found in the atolls, or islands surrounded by coral reefs, of Ari, Huvadhu, and Haddhunmathi.

Although several methods of cowrie extraction have been recorded, the one used most frequently was the ‘wading’ method. This involved going into sea at about hip-level and pulling cowries off stones beneath the shallow surface. With this method, around 12,000 could be gathered by a single person in a day. Notably, this labor would be done primarily by Maldivian women. However, this changed in the 19th century to include men, most likely due to high demand.

10th century Muslim traveler and historian al-Mas’udi records that from the sea, shells would be placed on shore, where the unfortunate inhabitants of these shells would be dried out under the heat of the sun. Four centuries later, however, one of the most famous Muslim travellers, Ibn Battuta, records that shells would be buried underground in pits instead. After an intensive cleaning process with both sea and freshwater, they would be wrapped into bundles made from coconut leaves called kotta, which numbered 12,000 shells.

Whichever method was used, the result was the same—once the animal was dried out, the shell transformed from a part of the Maldivian biological ecosystem into a commodity ready to be exchanged between merchants operating in the Indian Ocean trade network.

Ancient Cowries

Cowries have been found at archaeological sites associated with the Shang Dynasty in China (1600-1046 BCE), the Indus Valley Civilization (3300-1300 BCE), and the Mauryan Empire (322-185 BCE). The 1250 BCE tomb of Lady Hao (or Fu Hao), the favorite wife of Shang emperor Wu Ding, revealed over 6,800 cowries alongside jade, various metals, and other important objects. The cowries were definitely imports, and their presence within such a sacred space as an elite burial speaks to the high value ancient Chinese society placed on cowries.

This also seeped into currency—due to the distance between China and the Maldives, cowries were not easily incorporated into the monetary system. Yet, they did not abandon the idea of cowries as money completely. Although the role of cowries within as currency in ancient China is much debated, cowrie-shaped objects were carved from materials such as stone, jade, metal, and bone. However, by the end of the Han Dynasty, these faux cowries would become replaced entirely by metal money in the form of coins.

Cowries as Currency: Bengal and Thailand

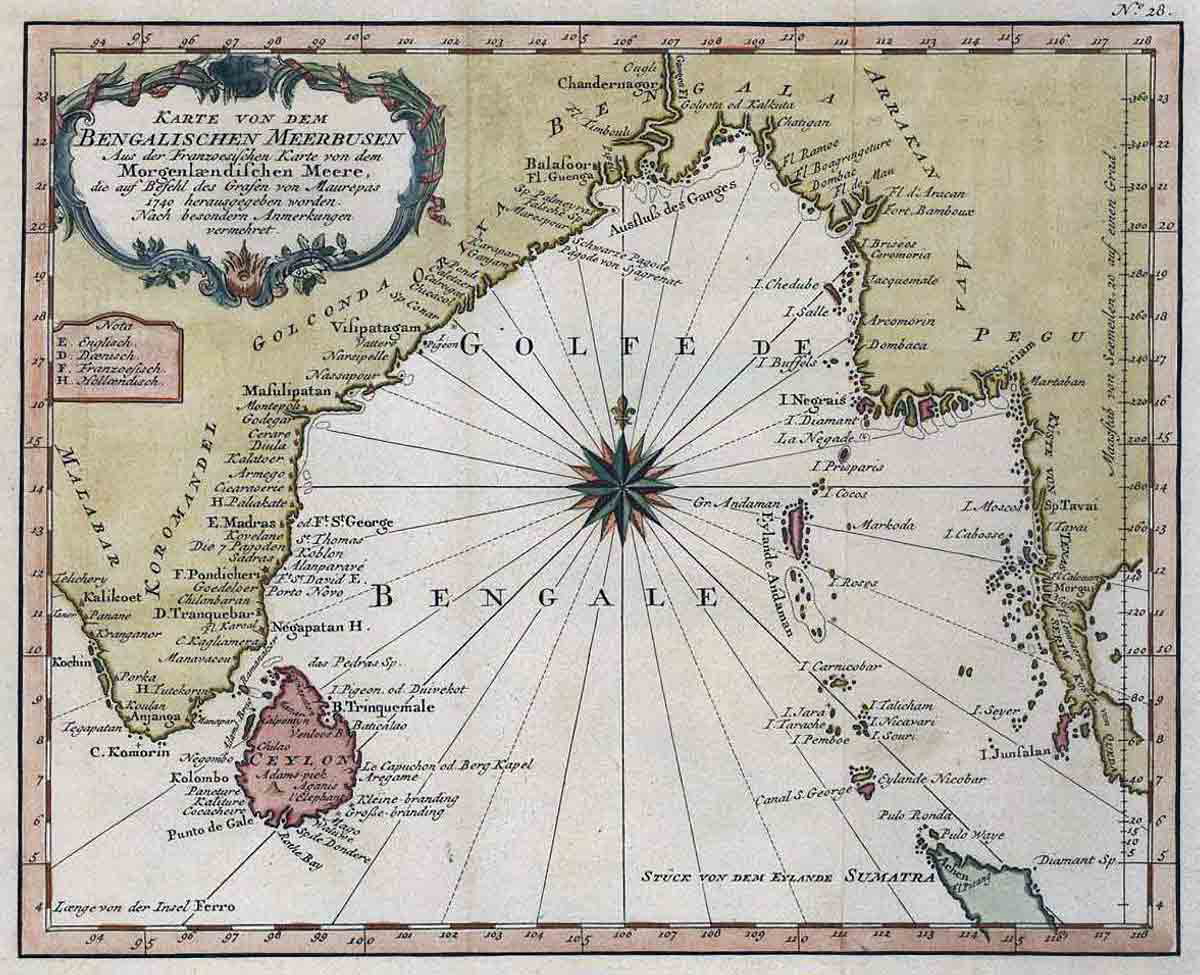

After being plucked out of Maldivian beaches, cowries would await export. Notably, cowries were not used as a form of currency within the Maldives itself, which used silver coins. The Bay of Bengal was one of the main export regions for cowries. This could have been due to the abundance of rice in this region, a diet staple of Maldivians. 14th century Chinese traveller Wang Dayuan even noted that one shipload of cowries would be sent in exchange for a shipload of rice.

Through this exchange, the Bay of Bengal gained a steady influx of cowrie shells. By the 7th century CE, these were incorporated into their monetary system, alongside gold, silver, and also pearls. Over time, cowries began to be used for small transactions, followed by silver, then gold for larger transactions. In the Bay of Bengal’s Odisha province, Wang Dayuan recorded that 250 cowries could be exchanged for one basket of rice.

Bengal also became an exporter of cowries to regions in the east, specifically on the monsoon trade routes to Southeast Asia. In present-day Thailand, cowrie shells were used as a form of currency. The Mangrayathammasart, a 13th century legal code promulgated by King Mangrai of Chiang Mai in present-day north Thailand, listed cowries as a form of payment for fines, alongside silver coins. Cowries would also be used for purchasing clothes, animals, tools, enslaved people, and even land. Cowrie shells were even used to incentivize soldiers. Allegedly, King Mangrai would provide soldiers with cowries and silver before battle, enticing members of Chiang Mai society to serve in his army (Baker and Phongpaichit, p. 98). Cowries were later used by the Kingdom of Ayutthaya in central Thailand, a major node in the Indian Ocean trade.

Cowries, Culture, and Currency: Pre-1500’s West Africa

In an age of paper money, metal coins, and cards as common means of exchange, the concept of shells as currency may sound inefficient. However, cowrie shells were impossible to forge, were not easily broken, could not be melted down into something else, and were always of a similar size, shape, and weight. Besides currency, they could be easily incorporated into any ritual, ceremonial, or everyday object. This was especially the case in many regions throughout East, Central, and West Africa.

The eastern coast of Africa, specifically from southern Somalia to Mozambique, is often referred to as the Swahili coast due to the presence of a unified Swahili culture. The Swahili coast was home to its own species of cowrie, the monetaria annulus, which were mainly from the Zanzibar archipelago off the coast of present-day Tanzania. Although cowries also circulated in West Africa, these were typically from the Maldives, and arrived in West Africa after a one-year journey through the trans-Saharan trade network.

Maldivian cowries were present in West Africa at least by the 7th century CE. They were used as adornments in certain communities in the form of jewelry, headpieces, and as decorations tied into women’s hair. A 7th century burial at the site of Kissi (present-day Burkina Faso) revealed several cowries drilled with holes, strung together and placed in the location of the head, possibly a woman, as a form of a headpiece.

Cowries were also embedded with meaning exceeding the bounds of decoration—they were incorporated into rituals, ceremonies, objects, and became affiliated with symbols of fertility and protection. They also functioned as objects whose ownership demonstrated power and status. Further, at least by the 14th century, cowries were being used as currency in places like Gao (an inland city in present-day Mali).

“Sine Qua Non”: Cowries as the ‘Absolute Condition’

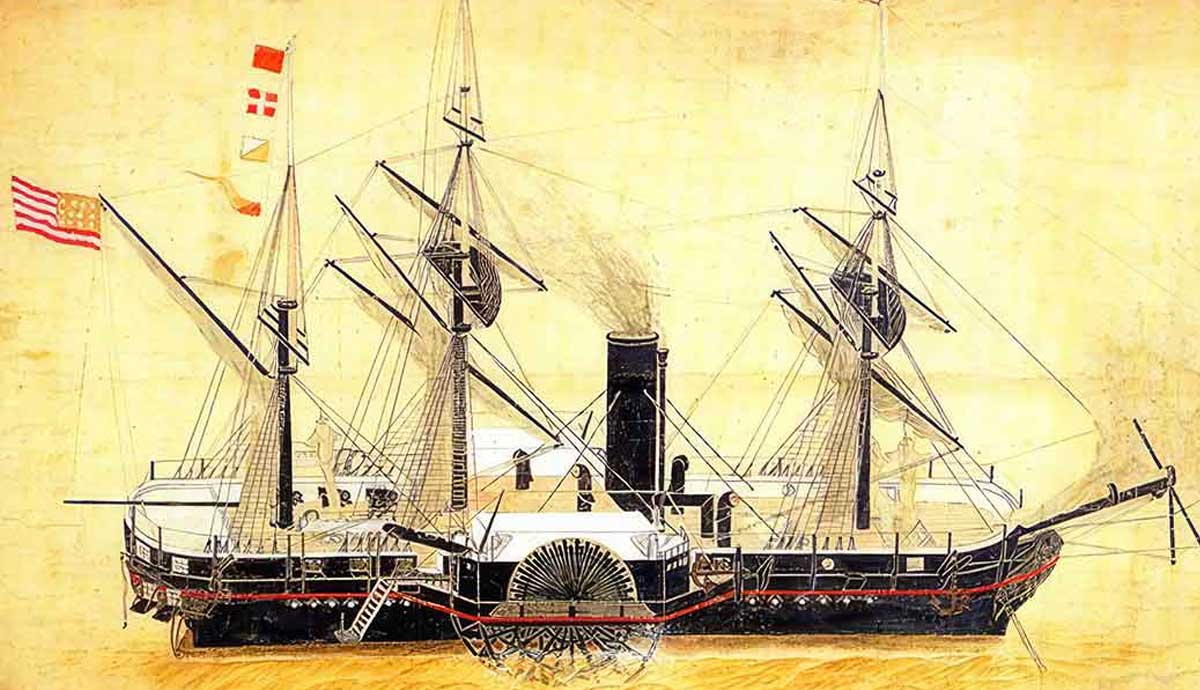

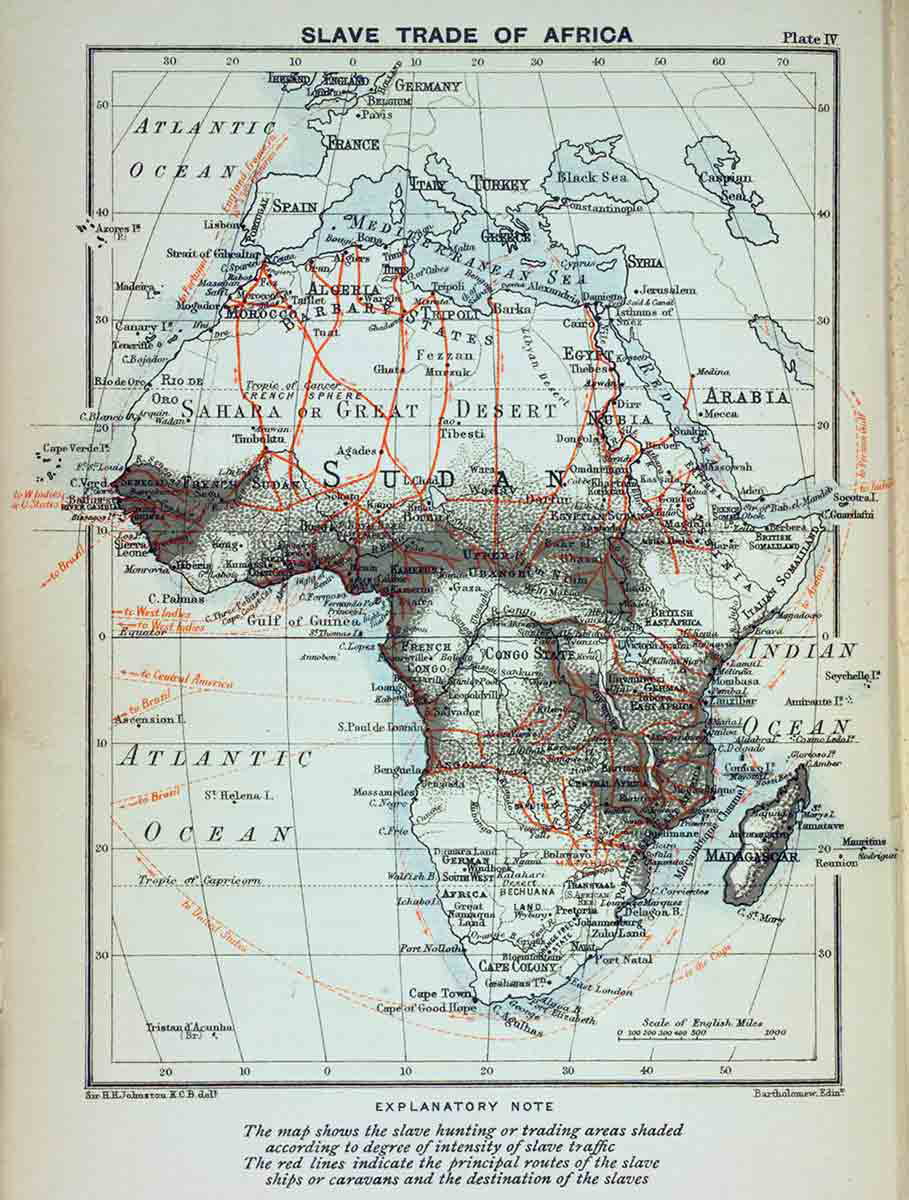

The longstanding history of cowries in West Africa was noted by the Portuguese in the 16th century, who understood that the societies they encountered on the West African coast, especially in the Bight of Benin (including present-day Nigeria, Ghana, Benin, and Togo), highly valued these objects and used them as a tool of monetary exchange. The Portuguese brought the first European shipment of cowries from the Maldives to the Bight of Benin in 1515. By 1690, cowries were an instrumental unit of exchange for European merchants to buy enslaved West Africans bound for the Americas.

Although cowrie shells were used in West Africa prior to European arrival, following the establishment of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, cowries filtered into West Africa in unprecedented numbers. In the late 17th century, cowries were 20-50 percent of the ‘purchasing price’ of a person (Heath, p. 61). This was 10-30,000 shells. By 1770, it rose to 160-176,000 shells. Cowries became the “sine qua non,” the absolute condition, to carry out trade with coastal West African leaders (Hogendorn, p. 32).

Cowries weren’t the only “currency of the slave trade” (Heath, p. 61). Other objects, consumables, and materials desired by West Africans leading the slave trade were also incorporated into trade transactions. Many of these objects came from European colonies throughout the Americas and Caribbean, and were often produced by enslaved West African labor—these were items such as sugar, alcohol, gold, and tobacco processed with molasses from Bahia (present-day Brazil). Gold dust would usually remain in the hands of Dahomean kings, while cowries would circulate in local markets and all strata of West African society.

Counting the Cowrie

Between 1700 and 1790, 10 billion cowrie shells were shipped from British and Dutch ports, like London and Amsterdam, to West Africa. A 1780 settlement between the Yoruba Empire and Dahomey Kingdom was made in 400 bags of cowries, the equivalent of £1,600 at the time. Today, this is the same purchasing power as approximately £247,540. However, how would this amount of cowries be accounted for and organized in transactions?

Once in West Africa, cowries would often be drilled with holes and placed on string in units of 40. A similar method of drilling and stringing cowries would also appear in East Africa. In the Buganda Kingdom of present-day Uganda, East African cowries were put on strings of 100, but could be halved or even broken down to units of five per string. In doing so, they could be used for transactions of varying value. Even in the above photo of a Shang Dynasty cowrie carved from bone, a visible hole was drilled in the back. This could suggest a similar way of keeping cowries organized, as far back as 1200 BCE or even earlier.

North American Cowries

Cowries even travelled as far as North America, where they were also used as currency in the fur trade between European settlers and merchants with various indigenous groups. Cowries were present at several indigenous burials in Queens, New York and Long Island. It is possible they were brought to North America by both the Dutch and French. Trading in a natural currency like shells would not have been foreign to European settlers—transactions already taking place between themselves and various Cherokee, Algonquian, and Iroquois Confederacy peoples who used wampam as a currency, which were tiny shell beads. Burials of the Arikara in South Dakota have also revealed over 44 cowries of the Maldivian monetaria moneta species, indicative of the spread of the trade in cowries.

From the Maldives to the World

Cowries from the Maldives appear all across the globe. They are present in regions as far as China in the east, and North America in the west, not to mention all the cultures and regions in between. Cowries were, and still are, a commodity that connected many regions and cultures throughout both time and space. They were the currency for transactional exchange for anything from objects to people. Both an economic tool and a cultural object, their significance remains today, albeit in more opaque ways. In West Africa, although cowries are no longer used as currency, the Ghanaian one cedi coin bears an image of a cowrie.

Sources

Baker, C., & Phongpaichit, P. (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heath Barbara (2016). Commoditization, Consumption and Interpretive Complexity: The Contingent Role of Cowries in the Early Modern World. Presented at Society for Historical Archaeology, Washington, D.C.

Hogendorn, J. S. (1981). A ‘supply‐side’ aspect of the African slave trade: The cowrie production and exports of the Maldives. Slavery & Abolition, 2 (1), 31–52.