As a site of great significance for three world religions, the Levant has been subject to brutal wars over the centuries. When Pope Urban II launched the First Crusade in 1095, the main target was Jerusalem and the Holy Land. During the First Crusade, the Christians successfully established four Crusader states, known collectively as Outremer. While the Christian territory shrank over time, they maintained a presence in the Holy Land for almost two centuries until what remained of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was conquered by the Egyptian Mamluks in 1291.

The Four Crusader States in the Holy Land

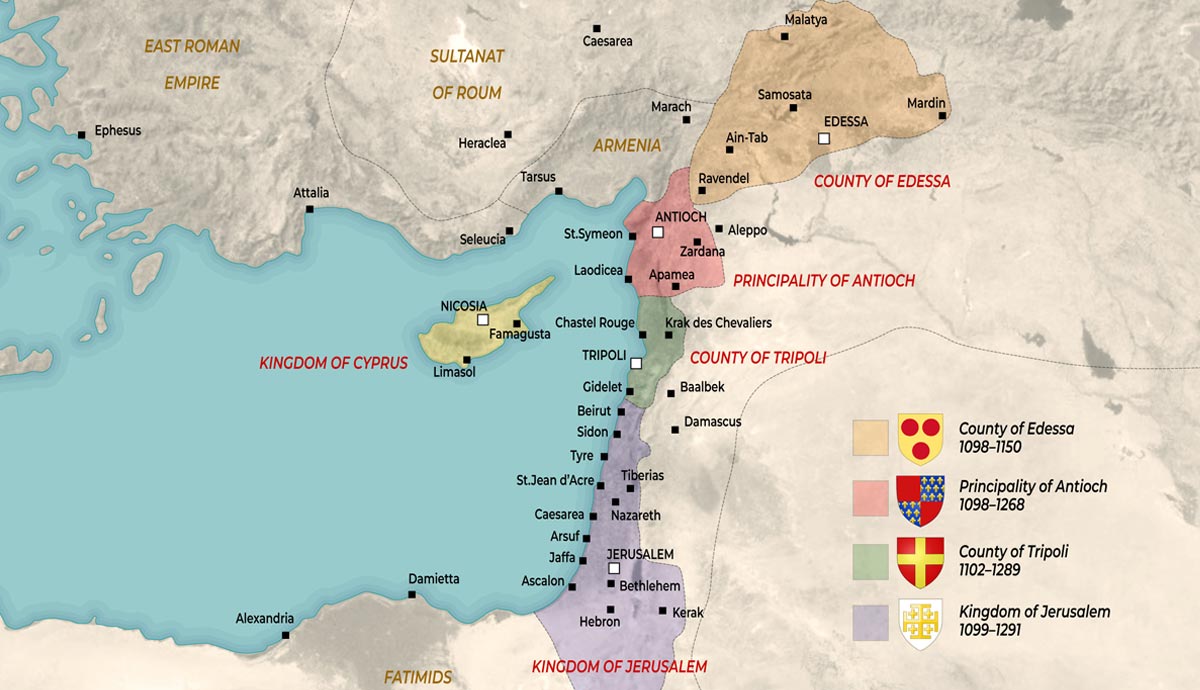

| Kingdom | Year of Establishment | Year of Collapse | Cause of collapse |

| County of Edessa | 1098 | 1144 | Conquered by the Zengids |

| Principality of Antioch | 1098 | 1268 | Conquered by the Mamluk Sultanate |

| County of Tripoli | 1102 | 1289 | Conquered by the Mamluk Sultanate |

| Kingdom of Jerusalem | 1099 | 1291 | Conquered by the Mamluk Sultanate |

Pope Urban II and the First Crusade

The Holy Land had been under Islamic rule ever since the Arab conquests of the 7th century CE. They generally left Jews and Christians alone, but the rise of the Seljuk Turks concerned Christian leaders in Europe. The Byzantine Empire, under the leadership of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, began a war with the Seljuks to push them out of Anatolia and requested support from the Papacy. Notwithstanding his prior conflicts with the Normans, Alexios’s plea was earnestly received by the Council of Piacenza, which heard reports of the brutal massacres of Levantine Christians by the Seljuks.

In 1095, Pope Urban hosted the Council of Clermont and called for an army of Christians to march on the Holy Land and drive out the Seljuks. Urban’s motivations were varied: he wished to cement Rome’s authority over European Christianity and he hoped that, by coming to the aid of Eastern churches, he could heal the Great Schism between Roman Catholicism and Byzantine Orthodoxy. Urban was a Frenchman and he began touring his homeland seeking French nobles to lead this expedition.

The First Crusade also became known as the People’s Crusade because of the large-scale involvement of Commoners in its ranks. A French priest from Amiens known as Pierre l’Ermite, or Peter the Hermite, led an army through the Holy Roman Empire and southeastern Europe. Another more professional force led by the leading knights of Europe also marched on a similar path.

Establishment of the Crusader States

One of the principal goals of the Council of Clermont was to establish Christian kingdoms in the Levant and Anatolia to counteract the Seljuk advances and the spread of Islam.

After advancing into Anatolia along with the Byzantine army, the Crusaders turned southwards and rapidly advanced against major Seljuk strongholds. Nicaea was captured in 1097, Edessa in March 1098, and Antioch shortly after in June. The main target of the Crusaders, Jerusalem, was taken in a siege in 1099.

Reinforcements ferried to the Levant by the Italian city-states of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa assisted the Christian advances. By 1109, they controlled Tripoli and seized several more Levantine cities in subsequent years.

The successes of the Crusaders were stunning considering that they were hundreds of miles from home. Local Christian communities varied in their reaction to these advances. For instance, some Armenians helped the Crusaders capture Antioch. In other cases, local Christian communities allied with the Seljuks. This created some tensions between these communities and the Crusaders. Once the conquests were complete, the Christian nobles who led their followers to the Levant started to establish various different feudal states.

The first Crusader state established was the Country of Edessa under the leadership of Baldwin of Boulogne. The second one was the Principality of Antioch, led by Bohemund of Normandy. The most powerful of the four was the Kingdom of Jerusalem, founded by Godfrey of Bouillon. Lastly, the County of Tripoli was established after its capture by Raymond of Toulouse and was the most independent of all four states.

Governance in the Crusader States

All four Crusader states had a similar form of political administration: they based their leadership on European feudal hierarchies. At the top of the realm was a king or prince, depending on the state. They ruled over a court of nobles, known as the High Court or Haute Cour. This court had much more power than its European counterparts and could elect or depose a regent depending on the circumstances. Members of the court were in charge of separate fiefdoms similar to what existed in medieval Europe.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was the most powerful of the four kingdoms owing to the strength of its military and the symbolic significance of ruling over Jerusalem. However, all four states struggled with the lack of effective governing structures and internal chaos. They relied heavily on the support of the Papacy and European monarchies to keep them stable in the face of attacks by different Muslim states. Their economies existed due to limited trade ties facilitated by the Italian city-states and taxes collected by the various nobles from the residents of their feudatories.

The Catholic Church was the most powerful institution in medieval Europe and it had a strong influence in the Levant. Various popes sent money and resources to each of the four states and ensured that they received support from Europe. At the same time, it competed with the Eastern Church for followers in the region. When this support dried up, the polities in Outremer became more precarious.

Demographics of the Crusader States

The four Crusader states were characterized by diverse and often stratified populations. Though ruled by Western European Christian elites, the vast majority of inhabitants were local non-Latin peoples. Catholics, primarily from France, Italy, and the Holy Roman Empire, formed the military and political aristocracy but remained a small minority. They settled mostly in urban centers and fortified positions, often establishing separate quarters from the local population. Catholic settlers included knights, clergy, merchants, and pilgrims who arrived during or shortly after the First Crusade.

The majority population consisted of Eastern Christians, such as Greek Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, Syrian Orthodox, and Maronite Christians, Muslims (Sunni and Shi’a), and Jews. Eastern Christians often served as bureaucrats, merchants, and farmers. While relations with Latin rulers were sometimes strained, they were often co-opted into administrative roles. Muslims, who made up a large share of the rural and some urban population, were subject to higher taxes and at times legal restrictions, but many continued their lives under Crusader rule with a degree of continuity.

Armenians, particularly in the County of Edessa, were influential allies. Many of them were involved in state administration. Jews were a smaller group, often confined to specific towns or quarters. They often suffered from Christian persecution based on the idea that they were responsible for the death of Jesus. Overall, the Crusader states were complex, multilingual societies shaped by cooperation, coexistence, and periodic conflict among their many ethnic and religious communities.

The Crusading Orders

To maintain order and defend against Seljuk and Mamluk attacks on Outremer, each Crusader state developed armies and stationed them in castles and outposts on the periphery. Each ruler had barons under their command who had anywhere between 10 and 100 knights as subordinates.

Crusader knights formed several military orders, the most famous of which was called the Knights Templar. Most knights fought on horseback, creating a formidable cavalry force that often overwhelmed the poorly-equipped Seljuk armies. The infantry consisted of men armed with spears, short swords, or longbows/crossbows that sought to exploit any breach created by the cavalry.

Most crusader armies numbered only a couple of thousand men. Except for the First Crusade, their armies were often outnumbered by the larger Muslim armies that attacked them. For instance, the Muslim leader Saladin organized a force of 20,000 men after uniting the Muslims of Egypt, Syria, and parts of Iraq. The Kingdom of Jerusalem, being the most populous Crusader state, could field the largest force, but even that paled in comparison to the Seljuk or Mamluk forces.

While the barons and knights were generally European, much of the infantry and mounted archers (Turcopoles) were recruited from local Christian communities. Armenian, Syrian, Maronite, and Palestinian Christians contributed large numbers of men to the Crusader armies. They served alongside European Christians who traveled to the Levant to fight against the Muslim armies during subsequent crusades. By the end of the 12th century, the Crusader states had become reliant on local levies to address their manpower shortages; even this did not prove enough.

Collapse of the Four Kingdoms

The collapse of the four Crusader states was a gradual process driven by internal weakness, lack of support from Europe, and increasingly effective Muslim resistance. The first to fall was the County of Edessa, captured by Zengi of Mosul in 1144. This event shocked Europe and triggered the unsuccessful Second Crusade. Edessa’s position far from the coast made it especially vulnerable. The remaining states survived but were shaken.

Over the next century, the Kingdom of Jerusalem suffered from dynastic instability, overreliance on military orders like the Templars and Hospitallers, and the decline in crusading zeal in Europe. Its pivotal defeat came in 1187, when Saladin defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of Hattin and recaptured Jerusalem, leaving only a few coastal cities under Christian control.

Though the Christians recaptured some territory such as the port of Acre during the Third Crusade, the Kingdom of Jerusalem never fully recovered. The Principality of Antioch and County of Tripoli held on until the late 13th century but were weakened by Mongol invasions and increasing pressure from the Mamluk Sultanate, which became the dominant Muslim power in the region. Antioch fell in 1268 to Sultan Baibars, a Mamluk Sultan from Egypt, and Tripoli followed in 1289.

Finally, the once-mighty Crusader presence ended with the fall of Acre in 1291, marking the collapse of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the end of Crusader rule in the Levant. The remaining Catholic enclaves were evacuated, and the region returned to Muslim control. The four kingdoms left a mark on the Levant, and the imposing ruins of their castles and fortresses can still be seen today.