Sun worship was particularly important to the early Romans, who were mostly an agrarian society. There is evidence of a cult of Sol among the Romans from the mid-Republican Period onward. However, it was a minor cult, and during the early Roman Empire, it fell into obscurity. As early as the 2nd century CE, the epithet Invictus was added to Sol’s name. Emperor Aurelian (270-275) established the cult of Sol Invictus as the supreme Roman deity, and it continued to play an important role even after his death. The identity of Aurelian’s Sol Invictus is a matter of debate. Some scholars have identified it with an eastern solar deity, either Elagabal of Emesa or Belos of Palmyra. The most recent theory suggests that Aurelian’s Sol Invictus was simply a continuation of the earlier Greco-Roman Sol.

What Are the Origins of Sol Invictus’ Cult?

According to Roman tradition, the cult of the god Sol was introduced by the Sabine king Titus Tatius, Romulus’s co-ruler, shortly after the founding of the city of Rome. This, like all other stories related to the oldest history of Rome, most likely came later and belongs to the domain of legend. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that the worship of the solar deity is one of the most ancient aspects of Roman religion.

The Romans classified Sol among the Di Indigetes, that is, among the original Roman deities, and he was often revered together with Luna, the personification of the moon. Based on the available sources, we can trace the cult of Sol from the mid-Republican Era onward. Earlier scholars believed that Sol was actually just the Roman version of the Greek god Helios. However, recent scholarship rejects this theory, and today it is considered that Sol was one of the oldest Roman gods.

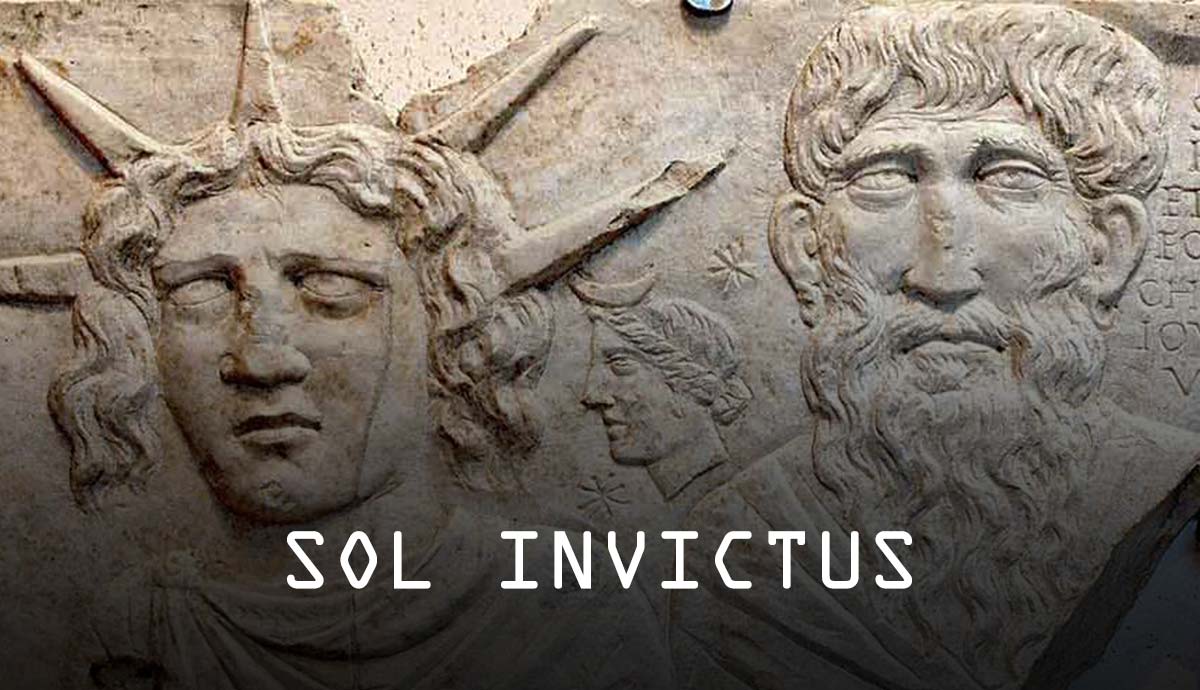

Among the early Romans, the cult of the sun played a very important role because of the special function of the solar deity in ensuring the fertility of the fields. The iconography of Sol, on the other hand, is taken from the Greek Helios. Sol was generally depicted with a radiating crown and in a chariot (quadriga).

The Cult of Sol Invictus

There were several temples in the city of Rome dedicated to Sol. The most important were the temple dedicated to Sol on the Quirinal and the temple of Sol on the Circus Maximus. In the temple at the Circus Maximus, there was a statue of Sol in his chariot. Sol had a special function as the patron of the circus, while Luna was the patron of circus chariots (bigae).

In the last decades of the Roman Republic, the restoration of old and forgotten cults became popular, among which was Sol. For example, Mark Antony gave great importance to the cult of Sol and represented it on his coins. Emperor Augustus continued this religious policy. After the conquest of Egypt, Augustus brought two obelisks to Rome. One was placed in the Circus Maximus, and the other in the Fields of Mars. Both were dedicated to Sol. In the temple of Sol on the Quirinal, the annual public sacrifice to Sol was most likely performed on August 9. In one calendar from the Augustan era (Fasti of Philocalus), August 9 is recorded as: Soli indigiti in colle Quirinali.

There were also priests of Sol, Sacerdotes Soli, whose existence is also recorded in several inscriptions from the era of the Principate. However, since the cult of Sol was minor, they did not belong to the upper social classes and probably did not have much influence.

Although the cult of Sol was minor, he occasionally appeared on Roman coins during the Empire. This shows that there was a clear continuity of the cult of Roman Sol during the Republic and the Empire. In the early Imperial Period, Sol mainly appears on the coins of Emperor Augustus. With the exception of Vespasian, he reappeared on coins only during the Antonine dynasty in the 2nd century CE.

Sol appears more often from the time of Septimius Severus (193-211). Usually, in older theories, the epithet invictus was considered to be of Eastern origin. However, the epithet invictus was used in Roman tradition for a number of deities, such as Apollo, Jupiter, Hercules, Mercurius, Saturnus, and Silvanus. The origin of the epithet invictus most likely dates back to the time of Alexander the Great, who was called “invincible” (ανίκητος) by the Pythia in Delphi in 336 BCE.

In the Roman world, Invictus was first used by Scipio Africanus and was also used in the time of Julius Caesar. The first emperor to use the epithet was Commodus, who called himself “the new Hercules.” The epithet was used for the god Sol from the middle of the 2nd century CE. The oldest inscription that mentions Sol Invictus dates from 158 CE.

Sol Invictus and the Cult of Elagabal

The assassination of Emperor Caracalla in 217 was followed briefly by the reign of Praetorian Prefect Macrinus. The plot against him was hatched by Julia Maesa, the sister of Septimius Severus’s wife, Julia Domna. She brought to power her fourteen-year-old grandson, Bassianus, who became emperor in 218. Bassianus came from a famous Arab family from Emesa in Syria. He, like his ancestors before him, served as priest of Elagabal, the Phoenician sun deity. After coming to power, he took the name Elagabalus and transferred the cult of Elagabal from Emesa to Rome.

The cult of Elagabal was known in the West even before Elagabalus came to power. For example, a dedication to Elagabal erected by a soldier in the middle of the 2nd century CE was found in Woerden (today’s Netherlands). However, Emperor Elagabalus elevated the god Elagabal above the traditional Roman deities and tried to impose him as the supreme god of the Roman Empire. This alienated the traditionally minded senators from him and eventually resulted in a conspiracy and his assassination in 222.

The central part of Elagabal’s cult was the sacred black stone (baetyl), which the emperor brought from the temple in Emesa to Rome. On the Palatine, near the imperial palace, a temple was built, which was known as the Elagaballium. In it, the young emperor performed all the rituals related to this deity. This included wearing make-up and exotic silk dresses, which further alienated the senators from him.

The senators themselves were forced to participate in these ceremonies and Elagabalus attempted to connect the cult of Elagabal with traditional Roman cults. He transferred to the Elagaballium a large number of important Roman religious artifacts, such as Vesta’s fire, the Magna Mater stone, and the Palladium. His most controversial act was marrying a Vestal Virgin, which was considered a great sin.

The official name of the cult was Sol Invictus Elagabal. However, this does not mean that the earlier mentions of Sol Invictus are connected to the cult of Elagabal or some other Eastern cult, as earlier researchers believed. As already noted, the appearance of Sol Invictus did not mark a new deity; the epithet was merely added to the Roman Sol.

The identification of Elagabal with Sol Invictus was an attempt by Emperor Elagabalus to create a syncretistic form of religion. Shortly after Elagabalus’s murder in 222, his religious reforms were reversed, and the cult of Elagabal soon disappeared from Rome.

Aurelian’s Sol Invictus

At the time when Aurelian became Roman emperor in 270, the Roman Empire was at the height of the so-called Third Century Crisis. Economic crises, political instability, and civil wars raged in the Roman Empire for more than three decades. Aurelian had to deal with the danger that threatened from three sides. First, he defeated the Germanic and Sarmatian tribes that ravaged the Balkans and Italy. After that, he re-conquered two breakaway states: the Palmyrene Empire in the east and the Gallic Empire in the west. Due to the reunification of the Empire, he received the title restitutor orbis (“restorer of the world”).

In addition to his military successes, Aurelian is best known for his religious reforms. After the reunification of the Empire in 274, Aurelian established the cult of Sol Invictus as the supreme Roman deity. In the same year, the magnificent temple of Sol Invictus was built in Rome on the Campus Martius.

A new board of priests was introduced: Pontifices Dei Soli, who, unlike the earlier Sacerdotes Soli, had a more significant position. Every December 25, the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti (birthday of the invincible sun) was celebrated with thirty chariot races. This was most probably also the date when the temple was dedicated. Also, every four years, from October 19 to 22, games were held in honor of Aurelian’s triumph.

The true identity of Aurelian’s Sol Invictus has long been part of scholarly debate. Older theories, which are based mainly on the available written sources, speak of an Eastern origin of Sol Invictus. For example, according to the Historia Augusta, during the Battle of Emesa in 272 CE, Aurelian’s army was victorious thanks to a divine apparition. After the battle, Aurelian had the same vision in the temple of the Sun in Emesa and therefore established the cult of that deity in Rome. This was accepted by some historians who equated Aurelian’s Sol Invictus with Elagabalus’s Sol Invictus Elagabal. Others have identified Sol with Belos, the patron god of Palmyra, based on the historian Zosimos (late 5th or early 6th century).

According to a third theory, which is increasingly accepted today, Aurelian’s Sol Invictus represents the continuation of the Greco-Roman Sol and not some new Eastern deity. Proof of this is provided by the iconography of Sol Invictus, which is completely identical to earlier depictions of Sol. On Aurelian’s coins, Sol Invictus is represented in the traditional manner, with a radiate crown holding a globe or a whip. The only innovation was the representation of Sol Invictus with his right hand raised, which many historians considered to be evidence of a new, oriental deity. However, the raised right hand was simply a traditional symbol of power.

Sol Invictus continued to appear on imperial coins after Aurelian, during the Tetrarchy, and until the reign of Constantine the Great (306-337). Early in his reign, Constantine promoted an imperial ideology that associated him with Sol, who was often depicted on his coins. Even after Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in 312, Sol Invictus continued to appear on his coins until 320, when it ceased.

The board of priests of Sol Invictus continued to exist for a century after Aurelian’s reign. Based on data from inscriptions, we know the names of fourteen priests in the period from the end of the 3rd to the end of the 4th century. However, during that period, Sol Invictus did not have the same supreme status as during Aurelian’s reign. None of the inscriptions are directly related to the cult of Sol Invictus, they are lists of priestly and other functions that these people performed.

In relation to the priests of Sol before Aurelian (Sacerdotes Soli), these priests all belonged to the senatorial aristocracy and held many important political and priestly functions. One of these senator-priests, Titanius, built a temple of Sol in Como between 286 and 293 on the orders of the emperor. The last inscription that mentions Sol Invictus is dated to 387 CE. It is a dedication to Vettius Agorius Praetextatus, a wealthy Roman senator who was also a priest of Sol.

Sol Invictus’ Associations With Mithraism and Christianity

Mithras was originally an Indo-Iranian solar deity. The cult of Mithras, which turned into a mystery religion, greatly expanded in the Roman Empire in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE. Many aspects of Mithraism remain unknown to this day due to the restricted nature of the cult itself. Since it was a mystery religion, devotees had to go through an initiation process that was a closely guarded secret. A central aspect of Mithraism was the tauroctony (the slaying of the bull).

Devotees were arranged on seven different levels and Mithraism spread the most among soldiers. It had the support of certain Roman emperors as well, such as Septimius Severus and Diocletian. In iconography, Mithras is often represented with depictions of the Sun and the Moon. As early as the 2nd century CE, Mithra was associated with Sol Invictus, and in the 3rd century, he was completely identified with that deity. In reliefs, Sol is often shown enjoying a banquet together with Mithras. In inscriptions, Mithra often appears as Mithra Invictus or Mithra Sol Invictus. In 308, Diocletian, together with the ruling tetrarchs, rebuilt the Mithraeum at Carnuntum and dedicated it to Sol Invictus Mithras.

There are theories that the date of Christ’s birth, December 25, was deliberately chosen to reduce the popularity of the pagan holiday Dies Natalis Solis Invicti. Early Christians associated Jesus Christ with the Sun, and solar symbols played an important role in early Christian art.