The ultimate intent of the leader of the Jacobins, Maximilien Robespierre, was to establish the Republic of Virtue in post-Revolution France. For him, the entire apex of the Revolution was to create virtuous men full of sincere civic morality, a new Republican morality. In a proclamation on May 7, 1794 (Floréal 18 on the Revolutionary calendar), he called for the inauguration of the Cult of the Supreme Being in the form of a grand festival. A transcendent cult could catalyze the Republic to greater glory.

The Enlightenment and a New Republican Morality

The notion of a civic religion dates back even further than the 1789 French Revolution. Its roots lie in Enlightenment principles.

In France, bouts of civic religions popped up during this period, like the Cult of Reason in 1792, which had an atheistic character despised by Maximilien Robespierre. He strongly believed in the Voltairean necessity of belief in a higher being for moral virtuosity,

“Republican virtue can be considered in relation to the people and in relation to the government; it is necessary in both. When only the government lacks virtue, there remains a resource in the people’s virtue; but when the people itself is corrupted, liberty is already lost” (On the Moral and Political Principles of Domestic Policy, 1794).

The Cult of the Supreme Being was a rival religion to the reactionary irreligion of the Cult of Reason. After the downfall of Robespierre and his Cult, Theophilanthropy was introduced by Chemin-Dupontès in 1796, who had similar ideas.

Rousseau’s Influence on the Cult of Supreme Being

There is little doubt that Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s political philosophy influenced the idea behind the Cult of the Supreme Being.

Rousseau’s deism is the foundation of Robespierre’s perfect religion. Robespierre was referencing Rousseau’s deism when he wrote, “I myself uphold those eternal principles by which human frailty can find strength to make the leap to virtue” (Smyth, 19).

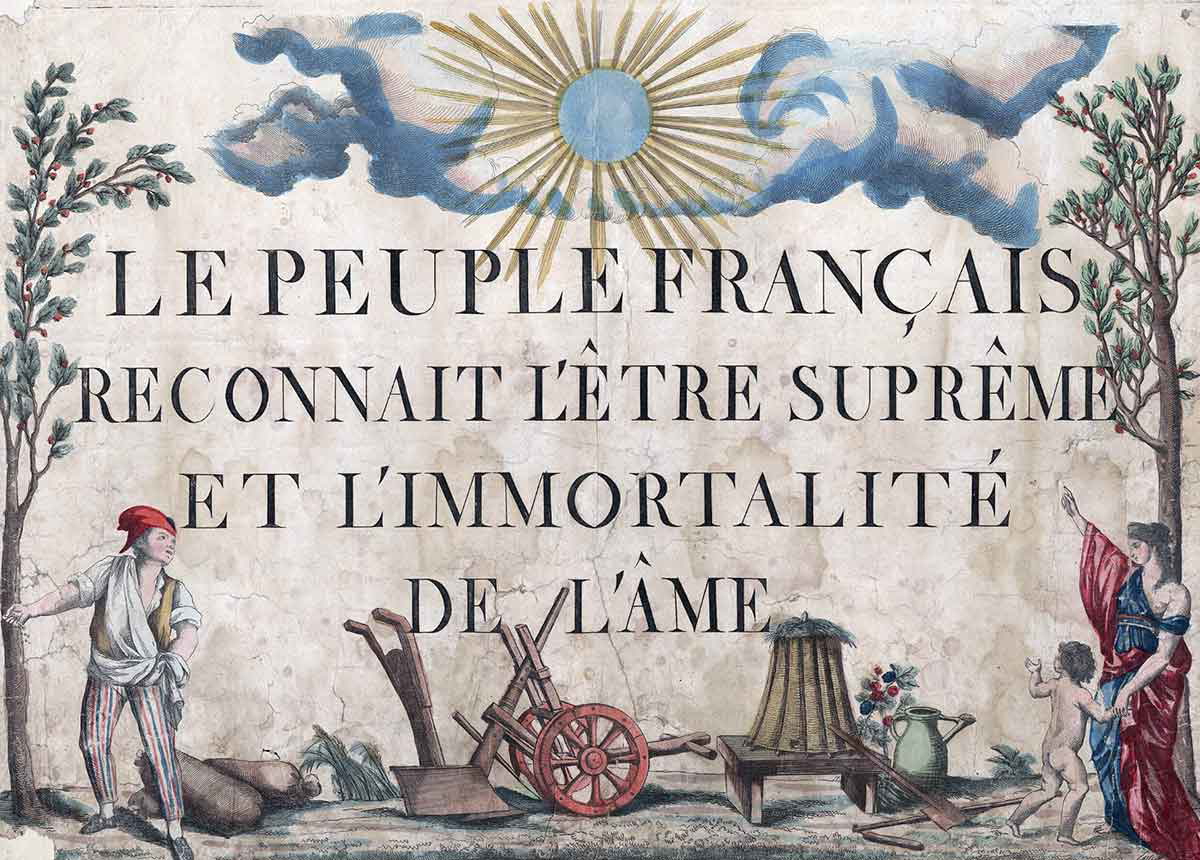

The shared assumption of the Enlightenment view of religion was that it was man-made and was contingent upon human intervention and configuration. This led to the popularization of a secular state in the French Revolution. Many of these philosophers and scientists had seen the brunt of religious wars in the 16th and 17th centuries and wanted a new, secular world order.

Rousseau’s view of nature transcended beyond his society’s religious mold and conflicts. In his novel Émile, he proposed a new concept of all religions as variegated external expressions of a universal essence of nature. Thus, no religion was “false,” and there was a converging “natural religion” at the heart of all religions. Various religions were malleable to human imagination and could be constructed to improve a civic polity.

This is where Robesierre’s rejection of the dogmas of Catholicism and its clergy meets his deep abhorrence of rising atheism in the new French Republic: “We do not claim to cast the French Republic in the Spartan mold; we want neither the austerity nor the corruption of a cloister.” The answer inevitably was Republican Deism.

The Festival of the Cult of the Supreme Being

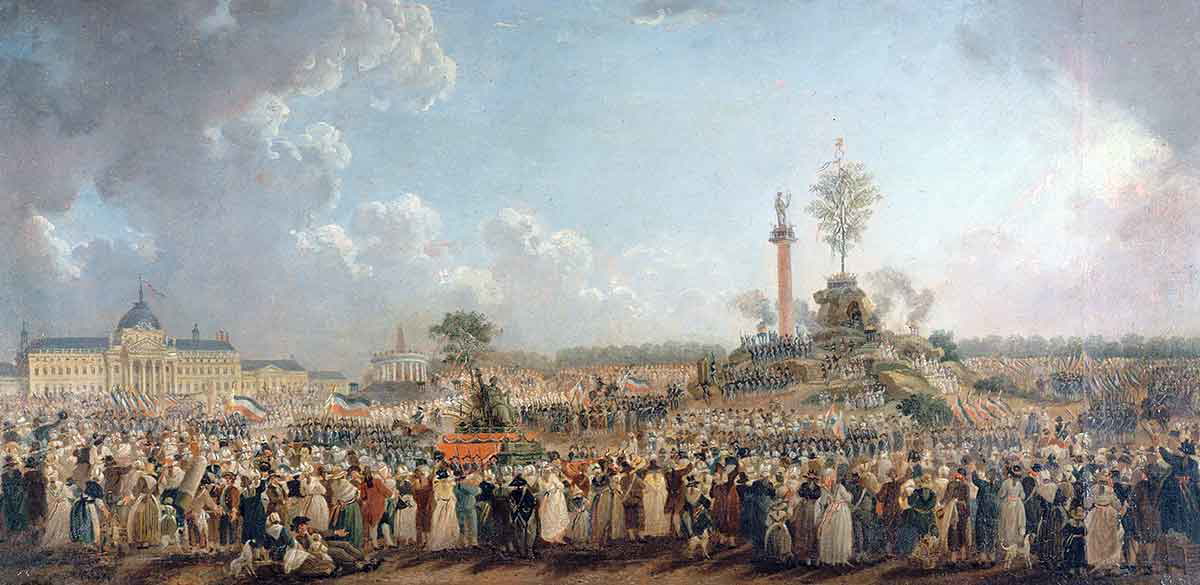

The Festival of the Supreme Being was held on June 8, 1794, on 20 Prairial Year II in the Jacobins’ Revolutionary calendar.

This festival was incredibly significant for Robespierre’s overarching political philosophy, as he indicated in his speech:

“There is one type of institution which must be considered an integral part of public education, by which I mean the national festivals. Bring men together and you make them better…give a great moral or political meaning to their meeting and love of the truth will fill their hearts” (Smyth, 19).

The individual’s venerated love of patriae by way of the Supreme Being in a festival setting would lead to soaring unity and morality. The festival took place in Paris, with many spin-offs throughout France. Its popularity was undeniable.

One of the most celebrated and famous French artists, Jacques-Louis David, was tasked with creating a detailed, grand plan for the festival along with the actor François-Joseph Talma. It took place at the apt location of an artificial mountain at Champ de Mars. There was classical Republican symbology everywhere with methodical requirements for men, women, children, and the elderly, just like a true religion. The Festival was a visionary spectacle, captured so wholesomely by patriotic artists of the time. It had a theatrical quality, with many actors and performers participating.

Setting a Grand Scene

2,400 deployed delegates from different sections of Paris gathered as a vast chorus group. At the crescendo of the drama, they sang in unison the “Marseillaise,” or the new “Hymn of the Supreme Being,” written primarily for the Festival.

The parade had a massive crowd that formed a long procession. In the center was a triumphal chariot drawn by eight oxen with golden horns. The wagon bore the symbols of labor, such as a printing press and a plow. Blind children sang a “Hymn to Divinity.” Later, mothers marched with roses, and fathers led their sons armed with swords.

There was a towering plaster-and-cardboard mountain. On its peak, standing on a fifty-foot column, was a colossal Hercules, sculpted with miniature figurines of Liberty and Equality in his hands. The three statues represented truth, courage, strength, and labor.

An enormous tree also symbolized the Republic’s ever-present growth and unity. Nature and its interconnection with the civic polity were the celebrated protagonists of the Festival of the Supreme Being. The ceremony climaxed with Robespierre descending the large mountain like the Jacobin prophet of the Supreme Being.

Symbols of the Cult

Many crucial symbols of the Cult and the Festival shaped the larger image and thought of Robespierre’s idea of the Republic. One doesn’t have to dig deep to discover that Robespierre’s revolutionary polity didn’t include virtue as a preeminent characteristic but rather virtue and terror.

His now famous speech is effervescent to this day:

“If the spring of popular government in time of peace is a virtue, the springs of popular government in revolution are at once virtue and terror: virtue, without which terror is fatal; terror, without which virtue is powerless. Terror is nothing other than justice, prompt, severe, and inflexible; it is, therefore, an emanation of virtue; it is not so much a special principle as it is a consequence of the general principle of democracy applied to our country’s most urgent needs” (On the Moral and Political Principles of Domestic Policy, 1794).

This is what the figures of Hercules or Liberty and the Hymns all amount to. There was a need for virtue and terror in mass politics. We observe this in the design of the costumes as well.

The festival celebrations inspired the national costume, including the red bonnets and striped trousers emblematic of the lower-class proletariats, sans-culottes. They were the prominent radical supporters and fighters of the French Revolution. The working class typified the working class, the majority in attendance at the festival. The message was clear: the embodiment of civic virtue is the people, while its metaphysical representation was the theistic Supreme Being.

The French Citizenry at the Festival

The festival’s arrangement looked like a Jacques-Louis David canvas, a painting completed by the post-Revolutionary people. The spectacle was littered with classical Republican ideals and symbols.

As discussed above, Hercules was an important mythic hero for the French Republic. He represented unity, crushing the monarchical powers of the old world. The image was stark and spellbinding. One of the most important symbols for Robespierre was categorizing gender roles.

A plan was meticulously created for the requirements of men, women, youth, elderly men, and even blind children, as delineated in the procession above. However, there was no role for older women.

In the festival plan, men and boys carried an oak branch, representing strength, morale, and knowledge. They were the foundation of this idealized society and perfect civic religion. Citizens wore the Liberty red cap, the official Jacobin freedom symbol. Historically, it was the Phrygian (Greek) cap or the Pileus (Roman) cap, illustrating freedom from the shackles of slavery. This came to signify the French Revolution, and Robespierre wanted that to be clearly shown in the festival.

Several of the tri-colored flags could be seen throughout the festival, too. The red, white, and blue flag had become France’s national flag after the Revolution. It concretised the three ideas of the revolution: liberté, égalité, et fraternité. The colors of clothes and flags showed the citizens what Robespierre hoped for his Cult and reassured their place in France.

Demise of Robespierre and the Cult

As history shows, the Cult of the Supreme Being was a short-lived, failed project. Even though victorious in many parts of France, the Festival ended up being the final nail in the coffin of Robbespierre’s demise. This was also happening at a time in his life when he was quite ill, and a short while after the Festival, Robespierre stopped making public appearances. Seeing this as an opportunity, his political opponents lead the public astray from the Supreme Being while campaigning against Robespierre’s vision. The fraternal joy the people had felt during the Festival also subsided.

Robespierre was in tense political trouble with his Committee of Public Safety colleagues. Since the Cult of Supreme Being had no godhead or prophet, interest in it waned after his execution on July 28, 1794. Napoleon Bonaparte, who seized power on 18 Brumaire Year VIII (November 9, 1799), banned the Cult and instituted the Catholic Church as the state church in 1801.

Bibliography

Smyth, Jonathan. Robespierre and the Festival of the Supreme Being: The search for a republican morality. Manchester University Press, 2016.

Robespierre, Maximilien and Žižek, Slavoj (Intro). Virtue and Terror. Verso, 2008.

Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Vintage Books, 1989.

Ozouf, Mona. Festivals and the French Revolution. Translated by Alan Sheridan. Harvard University Press, 1988.