Even though they have been linked together by history, the English artists John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti were two very different artists with two very different personalities. While Rossetti’s artistic output conveyed sweeping emotion and mystical fantasy, Millais’ works seemed to grow simpler and more direct as his career progressed. In spite of the different directions in which their careers took them, in 1848, a mutual dissatisfaction with the direction of British art brought them together to form the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

The Roots of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais

Both Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais claimed heritage outside of the British mainland. The patriarch of the Rossetti family, Gabriele Rossetti, ultimately settled in England after being forced to leave his homeland of Italy due to his Bonapartist political views. Millais’ family roots, in turn, came from the island of Jersey off the coast of France. Both men felt a deep sense of pride in the origins of their families that lasted throughout their lives, with Rossetti preferring to be called by his middle name, Dante, out of pride for the poet who shared his heritage. Similarly, Millais was deeply interested in his own family’s Norman origins and how they related to the island’s history.

From an early age, it was apparent that both children had great artistic potential. In the case of Millais, it was his mother who initially observed that he had a gift and helped to prepare him for his destined career. His talent was soon acknowledged publicly, as he was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools at the age of just eleven years. Rossetti’s early education was also prestigious. By the early 1840s, he was a student at the respected Sass’s Drawing Academy, in the hopes of being admitted to the Royal Academy Schools. His early works, such as his ink drawing Ulalume, show a natural talent for scenes that convey deep and powerful emotion. Nurtured by their families, the early lives of both Millais and Rossetti eventually led them both to the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

The Founding of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Rossetti and Millais met while both young men were studying at the Royal Academy. In September 1848, along with their friend and fellow student William Holman Hunt, the three artists studied a book of medieval Italian frescoes and became convinced that European art had fallen into decline since the career of Raphael, the great master of Renaissance painting. This conclusion was what inspired the formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the artists’ subsequent rebellion against the Renaissance-inspired art the Academy promoted. In their manifesto, these artists stated their desire to express “what is direct and serious and heartfelt…to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote.” Both Rossetti and Millais spent the following years struggling to determine what art committed to this noble but elusive ideal would look like.

Rossetti, for instance, was deeply hurt by the poor reception to his 1850 painting Ecce Ancilla Domini!. This scene, depicting the Christian scene of the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary, seems to have set the precedent for future Pre-Raphaelite depictions of red-haired women in ethereal settings. Shortly afterward, Millais completed another extremely influential work for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, known as A Huguenot, on St. Bartholomew’s Day, refusing to shield himself from danger by wearing the Roman Catholic badge. This work depicts a Huguenot, a French Protestant of the sixteenth century, gently resisting the attempts of his Catholic sweetheart to attach an armband worn solely by Catholics to his arm. The young man, about to face death because of his Protestant religious convictions, exemplifies the medieval ideal of steadfast courage in the face of danger that would come to exemplify the heroes of Pre-Raphaelite art.

Collaboration on “The Germ”

The early members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood did not solely create separate works of art. Throughout the movement’s history, artists worked together on collaborative projects in which they presented their shared vision. In the early stages of the Brotherhood, Millais and Rossetti worked together, along with other artists who shared their ideals, to create the magazine The Germ. This magazine largely consisted of poetry written by the group and often set the tone for future works of art, perhaps most effectively in the case of Rossetti’s famous poem The Blessed Damozel. The poem is filled with evocative language, vividly describing heavenly imagery associated with the poem’s heroine. For instance, the opening stanza describes the heroine’s appearance, stating:

Her blue grave eyes were deeper much

Than a deep water, even.

She had three lilies in her hand,

And the stars in her hair were seven.

This type of language appears to have set the precedent for the mystical and otherworldly paintings the group later created. Indeed, Rossetti himself created a work sharing the same title as the poem that was defined by its emphasis on surreal imagery, such as visions of the poem’s central couple embracing and the solemn angels directly below the heroine. The magazine’s sketches also assisted in setting the tone for the group’s overall artistic output.

An unused sketch by Millais inspired by one of Rossetti’s narratives, called St. Agnes of Intercession, transports the viewer to a medieval world, much like the world that initially inspired the group in 1848. With their somewhat awkward limbs and simple peasant garments, Millais’ work of art demonstrates the type of “heartfelt” and sincere vision that the Pre-Raphaelites aspired to illustrate. Although unused, it captured a sentiment that Millais, Rossetti, and all of their followers emulated in their later works.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Later Pre-Raphaelites

Both Rossetti and Millais went on to have a lasting and palpable influence on Victorian art. In the case of Rossetti, this influence was most strongly felt by younger generations of Pre-Raphaelites. As the 1850s progressed, two students from Oxford University, namely William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, felt drawn to Rossetti’s unique vision and even collaborated with him on a series of murals for the Debating Hall of the Oxford Union. Due to technical issues with the production of the murals, they are difficult to make out today. Nevertheless, their production seemed an extension of the course that Pre-Raphaelite art had begun to take in Millais and Rossetti’s early works. Inspired by the legendary tales of King Arthur and his knights, these murals celebrate medieval ideals of chivalry and valor, thereby returning to the Pre-Raphaelites’ initial goal of lifting up the “heartfelt” in art.

Burne-Jones and Morris, both influential Victorian artists in their own right, took up these themes throughout the works of art that they created throughout the rest of their lives. They can be particularly strongly felt in the projects that Morris and Burne-Jones worked on together, such as a pair of tapestries the two collaborated to design for their interior design firm, Morris & Co.

The tapestry from this pair featured above, depicting the Greek goddess of fruitfulness, strongly evokes medieval tapestry through its emphasis on the detailed array of flowers and fruit surrounding the central figure. The goddess’ long, rose-colored gown also assists in transporting her into a medieval setting in which she dwells in harmony with nature. This heavy emphasis on detail to create an immersive world was a key source of inspiration for many generations of British artists to come, including Arts and Crafts artists such as Walter Crane and Art Nouveau artists such as Margaret MacDonald.

John Everett Millais and the Future of Modern Art

Towards the end of the year 1853, John Everett Millais was voted to receive a position at the Royal Academy, prompting Rossetti to bemoan in a letter, “the whole Round Table is dissolved.” Millais’ work appeared to drift farther and farther away from the initial forays into Pre-Raphaelitism he made between 1848 and 1853 in the following years. His later work did play a major role in the development of a movement that later attracted Rossetti himself, known as Aestheticism. A particularly important work in this shift that was highly influential on Aestheticism was his 1856 painting Autumn Leaves. Autumn Leaves depicts a group of young girls piling a stack of dead leaves in the English countryside on a beautiful fall evening. The painting has less to do with encapsulating an ideal of authenticity than Millais’ earlier work. Instead, it is about capturing a beautiful moment.

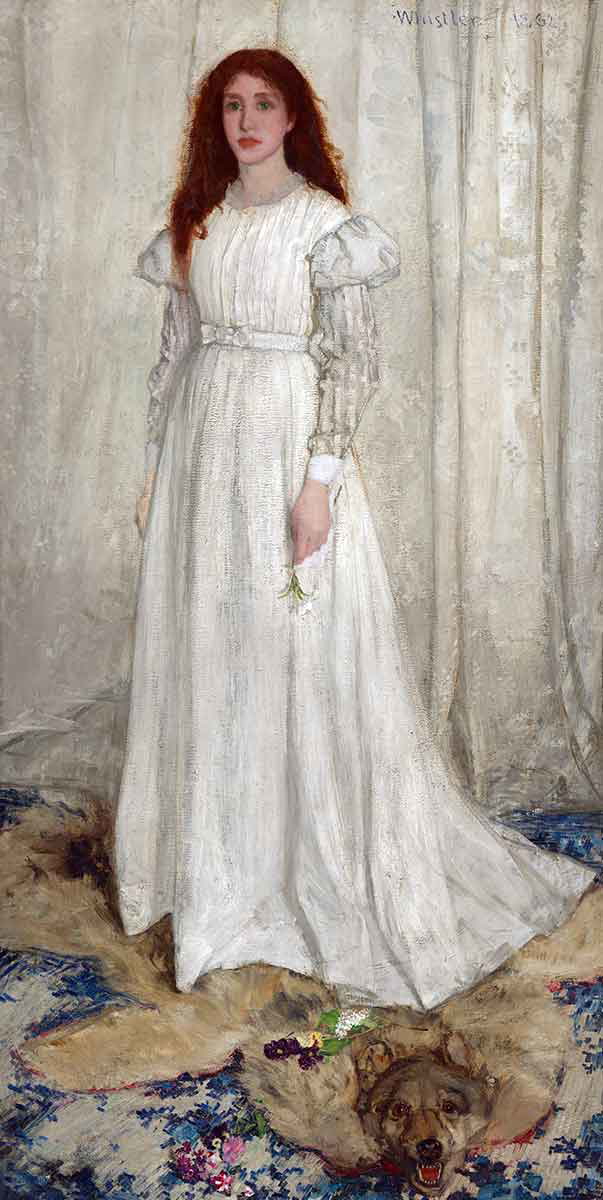

The reverberations of this approach can be felt in the works of artists associated with the Aesthetic Movement, such as Symphony in White No. 1: The White Girl by James Abbott McNeill Whistler. In this work of art, the artist swathes his subject in a white dress against a white background, resulting in a simple painting that encourages a viewer to interact with it on a sensory level rather than an intellectual one. This new approach was a seminal one in the development of modern art in the twentieth century. Interestingly, the attire and expression of the model for Whistler’s painting evoke the central figure, young Sophie Gray, in Autumn Leaves. These similarities seem to be evidence of the significant foundational role of Millais, both within the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and in the world of Victorian art at large.