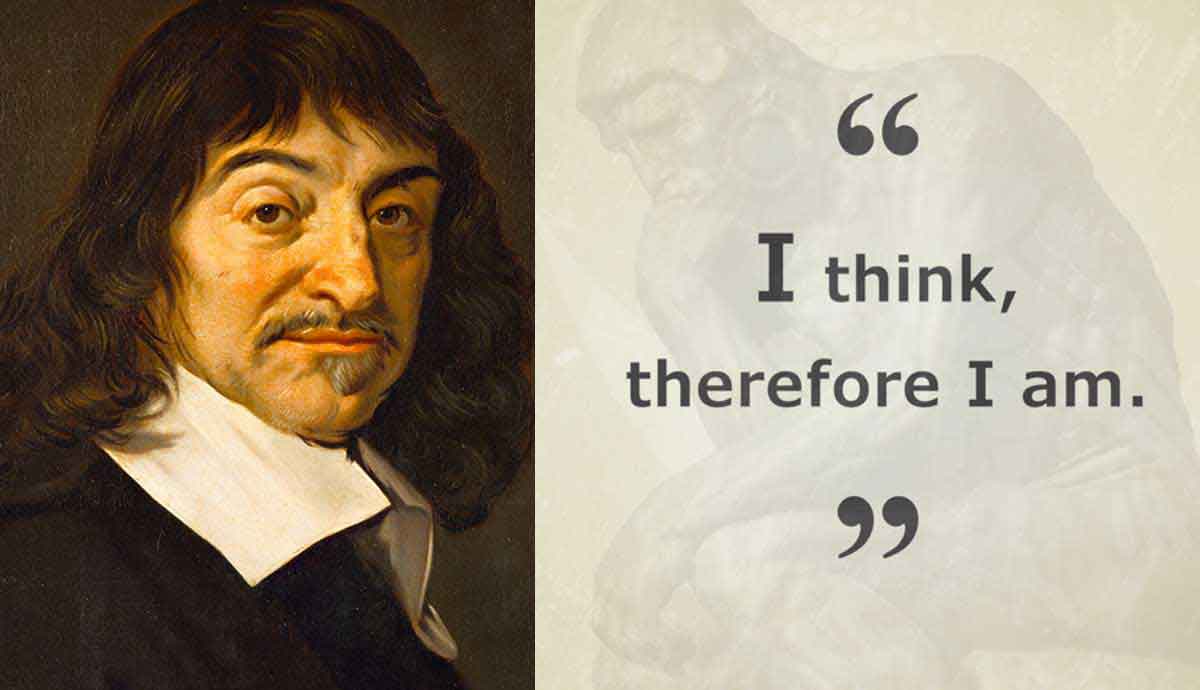

René Descartes (1596-1650), the philosopher and mathematician whom many say is the father of modern philosophy, sought to secure the ultimate foundations of knowledge. But this ambition arguably traps him in the “Cartesian Circle:” To have a secure foundation for knowledge, Descartes must first know God exists; but to know God exists, Descartes must first have a secure foundation for knowledge. His epistemological project appears to assume what it wants to prove. In this article, we will trace the origin of this “circle” and how Descartes might escape it.

René Descartes’ Method of Doubt: In Search For Knowledge

In his Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes finds himself troubled that much of what he once took himself to know is false. So he decides to “demolish everything completely and start again right from the foundations,” rebuilding the edifice of knowledge from the ground up (Descartes, 12).

This is surely impossible if Descartes must inspect each belief, one by one, for its merits. So he proposes the method of doubt instead: he will inspect the ‘basic principles’ on which his beliefs rest, and if he finds any reason whatsoever to doubt these principles, the entire structure built upon them will fall.

Doubting the senses—what one sees, hears, smells—is an easy first step. Descartes remembers they have deceived him in the past, which raises the possibility they will deceive him again in the future (Descartes, 12). Even worse, at any moment, Descartes could be dreaming, a possibility he cannot eliminate using the senses because this would require him to ‘step outside’ the dream—and to assume just what he wants to prove.

So Descartes must discard every sensory belief, dooming all the sciences studying ‘corporeal nature’ (such as biology, chemistry, and physics) as a result.

What about mathematics and geometry? Dreaming or not, two and two equals four, and squares have four sides, right? But Descartes maintains even these kinds of beliefs are in jeopardy. For an evil demon could conceivably exist who, as if we were brains in vats, may be able to ‘shock’ us into unwittingly believing mathematical falsehoods.

This possibility is slim, even outlandish. But the method of doubt leaves Descartes no alternative: in addition to sensory beliefs, he must discard all mathematical and logical beliefs, plus all the sciences they comprise.

Rebuilding Knowledge: Clear and Distinct Perception

Descartes now doubts what philosophers call a posteriori and a priori beliefs, respectively. What remains? His next move traces the first steps of the Cartesian Circle.

Notice that even if Descartes is deceived by an evil demon, this demon cannot make him doubt his own existence. To be deceived at all, Descartes must be the subject of that deception. Drawing from this insight, he writes: “So after considering everything very thoroughly, I must finally conclude this proposition, I am, I exist, is necessarily true whenever it is put forward by me or conceived by my mind” (Descartes, 17). ‘I am, I exist’, commonly known as the cogito, is therefore a foundational piece of knowledge because it passes the method of doubt.

But now things get tricky.

On one hand, because the cogito is a foundational piece of knowledge, Descartes can inspect it for a ‘mark’ that other pieces of knowledge might share; something that would make them safe. He finds that clear and distinct perception is this mark, writing: “In [the cogito] there is simply a clear and distinct perception of what I am asserting” (Descartes, 24).

On the other hand, Descartes notes that this mark is not sufficient for all knowledge because he “previously accepted as wholly certain and evident many things which [he] afterwards realized were doubtful” (Descartes, 24). Indeed, basic claims of mathematics seem as clear and distinct as anything, but Descartes’ evil demon hypothesis shows even these are doubtful. Clarity and distinctness are necessary for foundational knowledge, but not sufficient.

What’s the next move?

Descartes’ Strike: God is Essential to Knowledge

Descartes now makes a striking claim. He says he “must examine whether there is a God, and, if there is, whether he can be a deceiver. For if I do not know this, it seems that I can never be quite certain about anything else” (Descartes, 25).

That sounds alarming. To get a handle on it, let’s untangle two threads.

First, why is it important God is not a deceiver? The answer is actually straightforward. If God is not a deceiver, then Descartes can trust clear and distinct perceptions beyond the cogito. This is because a non-deceiving God eliminates the possibility an evil demon exists to make these perceptions untrustworthy.

This does not explain why God is not in fact a deceiver, however. So consider the second thread. Descartes maintains God is “the possessor of all…perfections” and “…it is manifest by the natural light that all fraud and deception depend on some defect” (Descartes, 35). God is not a deceiver, in other words, because this would force the contradiction of an imperfect perfect being.

So Descartes believes God is essential to knowledge because otherwise, he cannot securely rebuild his knowledge beyond the solipsism of the cogito. He needs an additional guarantee that his clear and distinct perceptions beyond the cogito are reliable.

The Cartesian Circle

The idea that we need a God to make sure we know anything at all is striking. In fact, it invites disbelief. But beneath it lurks a still more pressing question: why believe God exists at all?

Descartes gives a few arguments that God exists. Analyzing these requires an article (and much more) of its own. Because of this, it’s best to make a broader point here. Any argument that God exists risks assuming just what it wants ultimately to prove: that clear and distinct perceptions are reliable. So Descartes might be caught in a circle.

Here’s why.

Assume Descartes provides an argument that God exists. This argument will be comprised of premises and a conclusion. The conclusion will say God exists. The premises will be reasons to believe God exists. And these reasons must be good ones—we must have justification to believe them, as philosophers say—because otherwise, they will not justify the conclusion.

Now the problem arises.

If Descartes’ reasons to believe God exists are good, they should pass his method of doubt. But Descartes has argued that just his clear and distinct perception of the cogito passes the method of doubt. All other such perceptions pass only if one more condition is met: God is not a deceiver. But now, any argument that God exists must assume in its premises the primary consequence of its very conclusion: that clear and distinct perceptions are reliable. Otherwise, Descartes is stuck with the cogito and nothing else.

This is the infamous Cartesian Circle: to prove a God exists who would not deceive Descartes about his clear and distinct perceptions, Descartes must assume clear and distinct perceptions are already not deceptive.

Breaking out of the Cartesian Circle

Not all philosophers believe the Cartesian Circle dooms Descartes’ epistemology. Consider one attempt to break out of it.

The Cartesian Circle surely dooms Descartes’ epistemology if it is a logical circle. In this case, Descartes would assume as a premise in his arguments for God’s existence that clear and distinct perceptions are reliable to ultimately prove that (because God could not be a deceiver) clear and distinct perceptions are reliable. He would be assuming precisely what he wants to prove.

But it’s not obvious this is what Descartes does. Yes, his conclusion that God exists entails that clear and distinct perceptions are reliable. But he does not necessarily use this very same claim as a premise, tacit or otherwise, in his arguments for this conclusion.

Consider this difference (Van Cleve, 1979):

- If Descartes clearly and distinctly perceives something is true, then Descartes knows it is true.

- Descartes knows that if he clearly and distinctly perceives something is true, then it is true.

(1) says whatever Descartes clearly and distinctly perceives is true. (2) says Descartes knows that what he clearly and distinctly perceives is true. In the first case, Descartes has knowledge in virtue of a clear and distinct perception. In the second, he knows something about clear and distinct perception: that it gives him knowledge.

The distinction is subtle. Consider an analogy.

An infant might know his mother in virtue of seeing her, but not know that seeing her gives him knowledge. In the first case he knows his mother, in the second he knows (or, in this case, does not know) something about knowledge itself.

If Descartes’ premises in his arguments for the existence of God assume (2), then the Cartesian Circle is a logical circle. If they assume (1), then it’s not.

If Descartes’ circle is not a logical circle, then what kind of circle is it?

Is Descartes’ Circle an Epistemic Circle?

Readers might find the difference between (1) and (2) thin.

Fine, they might say, Descartes does not literally state as a premise in his arguments for the existence of God that clear and distinct perceptions are reliable. So, he is not guilty of logical circularity. But he still assumes this because if clear and distinct perceptions are not reliable, then he cannot know these premises anyways. So what’s the difference?

The difference is between what philosophers call logical and epistemic circularity. Unlike a logically circular argument, an epistemically circular argument does not literally assume what it wants to prove. Instead, it uses as premises specific claims that are justified if its conclusion, which is distinct from these specific claims, is true.

In Descartes’ case, he would know the premises of his arguments for the existence of God in virtue of clear and distinct perceptions, but not on the basis of clear and distinct perceptions.

So where does this leave us? Does Descartes believe God is essential to knowledge?

The answer appears to be ‘yes,’ but in a way that is much subtler than it first appears. To know something, Descartes does not think we must first know that God exists. But he does appear to think that God must exist in order for us to know something. Otherwise, there is no guarantee our clear and distinct perceptions are reliable beyond the cogito.

In more modern parlance, the philosophical lesson is that there is a difference between ordinary knowledge, say of mathematics, and knowledge of knowledge. Defanging the Cartesian Circle requires only the former.

Sources:

René Descartes, Cottingham, J., & Arthur, B. (1996). Rene Descartes : meditation on first philosophy : with selections from the Objections and Replies. Cambridge University Press.

Van Cleve, James (1979), “Foundationalism, Epistemic Principles, and the Cartesian Circle,”

The Philosophical Review 88: 55-91.