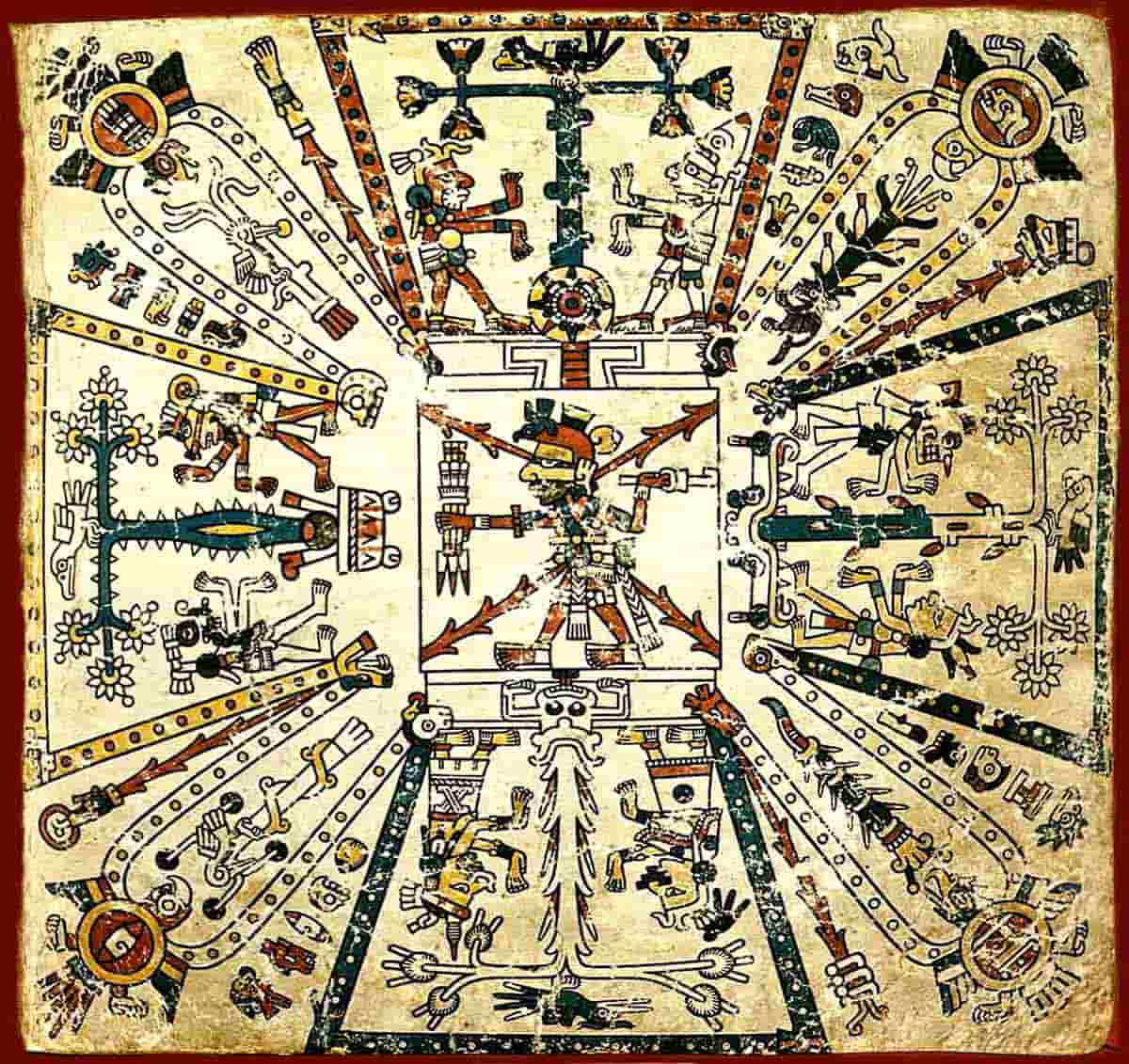

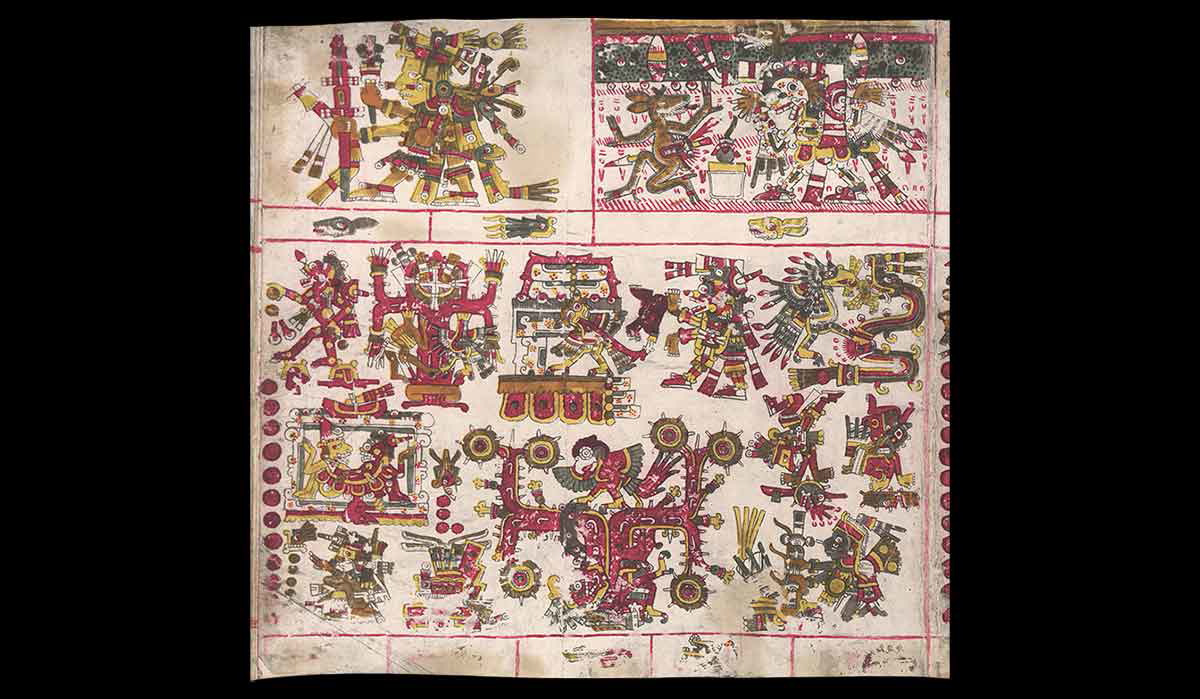

The Mesoamerican worldview, cyclical and dualistic, understood the universe as a system in constant renewal. The cosmos was organized into 13 heavens and nine underworlds arranged along a central axis, with the earth in the middle. Mictlan was the place where those who died in any way not associated with war, water, or premature birth would go. For four years, the dead would descend through nine levels, facing difficulties that would purify them until finally, they would come to rest in the final level of Mictlan.

First Level: The Separation

In some versions of the codices (pre-Hispanic records), Tlaltipac means “upon the earth” and must be understood as the outermost layer of the underworld. It is the first level of the journey toward Mictlan but is still within the world of the living, as it is the same physical space where life takes place. It symbolizes the moment when the soul leaves behind its body, marking the beginning of the separation between the material and spiritual worlds. In the Mesoamerican worldview, there was a belief that caves were entrances to the underworld.

Second Level: The Dog in the River

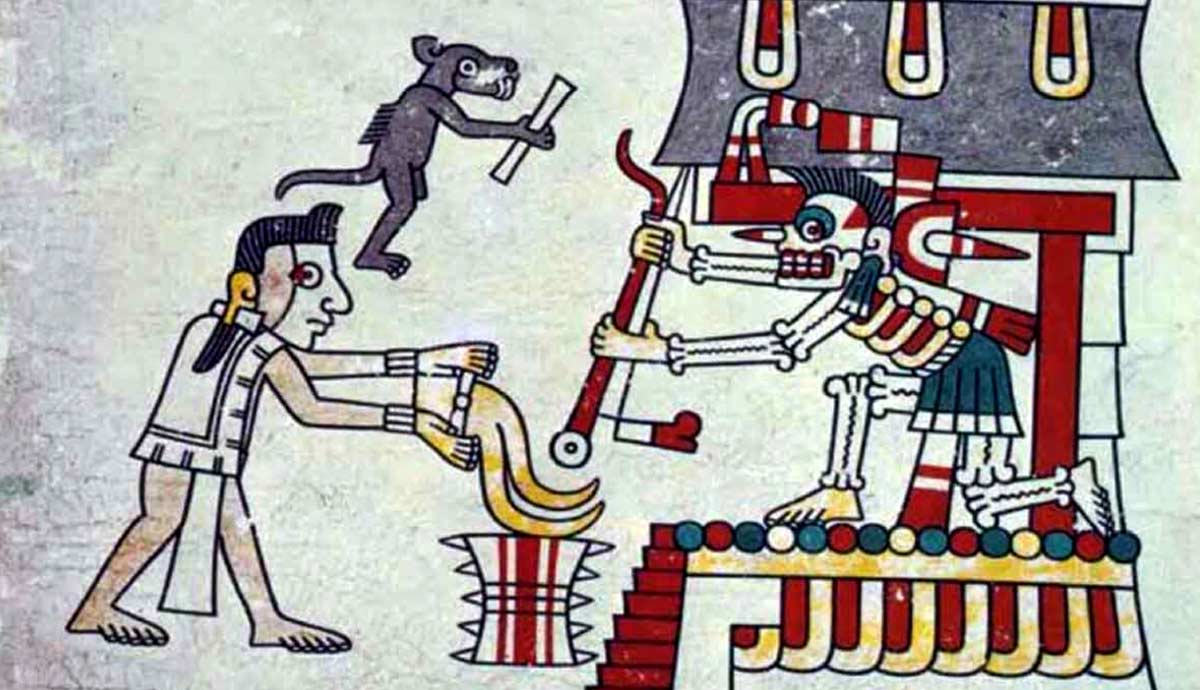

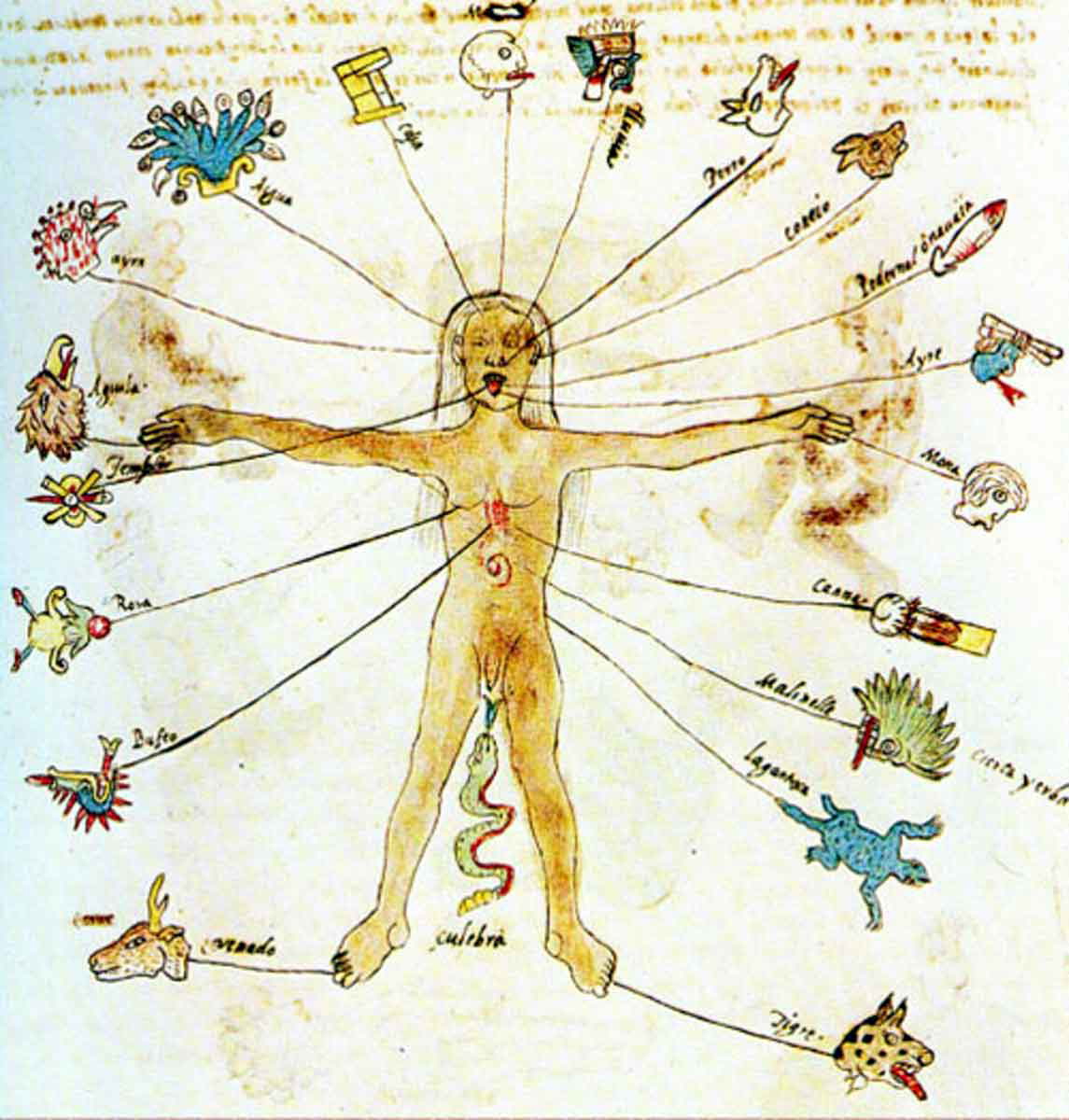

This level represented the border between the living and the dead. It was necessary to cross the river Apanohuaya with the help of a Xoloitzcuintle dog. These hairless dogs were considered sacred because it was believed that they could represent men in sacrifice and guide their spirits to the underworld. They were also linked to the god Xolotl, twin brother of Quetzalcoatl. While the latter, god of the morning star, of light, of the sky, of life, announces the rising of the star, Xolotl, the evening star, of darkness, the underworld, and death, takes care of transporting it in the afternoon and accompanying it on its daily journey through the realm of death, in the same way that the spirit of the Xoloitzcuintle dog transports that of men to Mictlan.

It was common to sacrifice a dog and bury it with the deceased; it was believed that preferably it had to be reddish in color because when its color was very dark, it meant that it could no longer carry souls since it had submerged many times in the river that leads to Mictlan, but if it was a very light color, it meant that it still lacked the maturity to be able to carry souls.

Third Level: Where the Mountains Meet

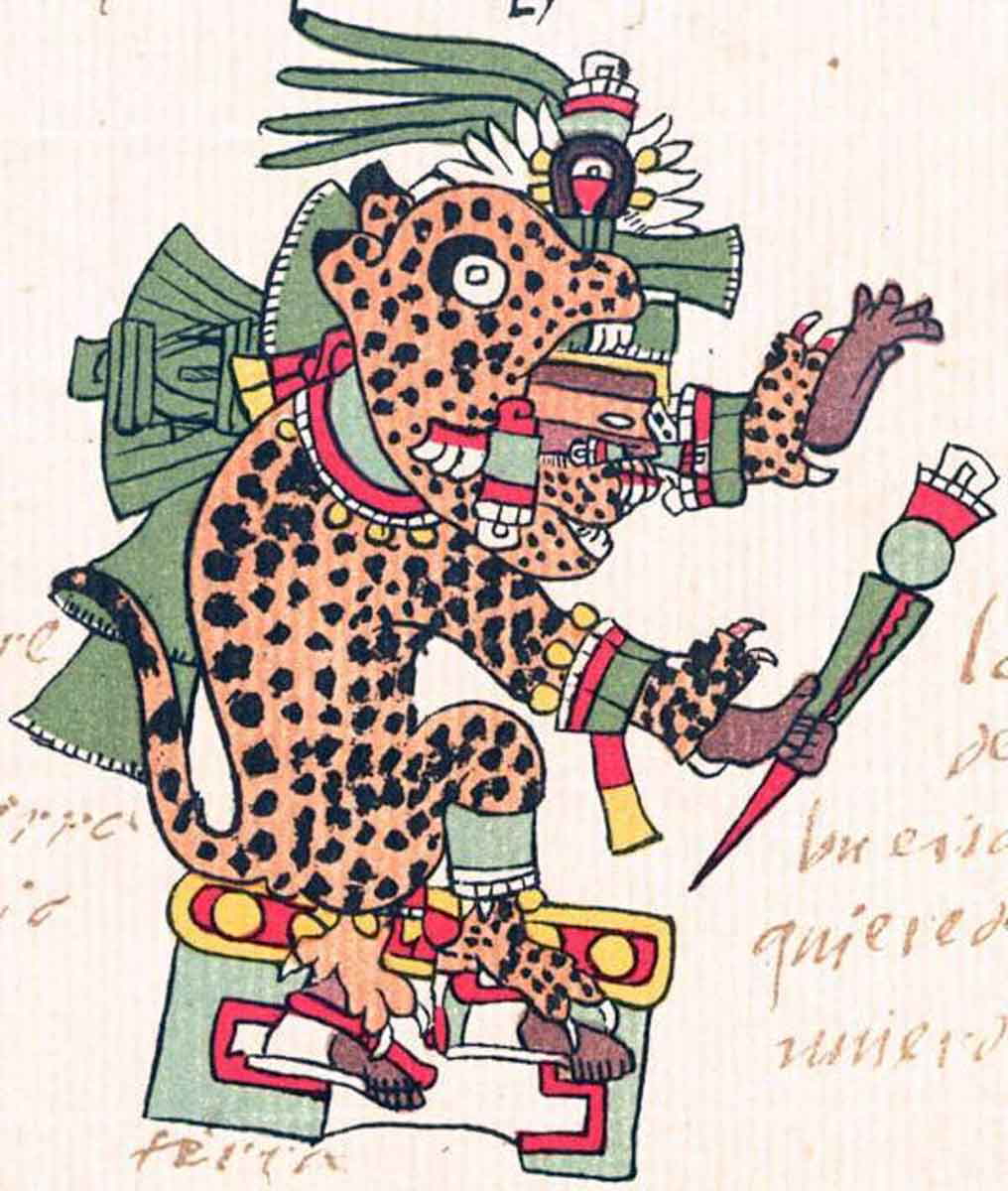

In this region, there were two enormous mountains that opened and closed, crashing into each other. Therefore, the dead had to find the precise moment to cross the mountains without being crushed. Possibly, the two mountains can be interpreted from Mesoamerican dichotomous thinking, in which one would represent life and the other, death. The action of them coming together may have been a symbol of the reflection that the dead person had to make about their new condition of “death” and accept it. Tepeyóllotl, god of the mountains and echoes, lord of the jaguars, reigned over this level.

Fourth Level: Obsidian Mountains

Continuing with the interpretation that the journey through the levels of the underworld served to decompose the human body, these obsidian mountains tore off the flesh, which would no longer be needed since it was only a vehicle animated by the three soul entities that dwelled in the body: the tonalli, housed in the head; the ihiyotl, in the liver; and the teyolia, in the heart. The teyolia was the essence that, once death occurred, after some time would manage to reach the end of the path.

In this level resides Itztlacoliuhqui, god of obsidian, punishment, sacrifice, disasters, and frost. In the past, he had been the guardian of the sun during dawn; however, in an attack of rage, he assaulted the god Tonatiuh and shot an arrow that pierced his head, and he was punished and consequently became this dark and cold god.

Obsidian, a volcanic glass formed from lava at temperatures above 600°C, was perhaps the most important raw material of Mesoamerica due to its physical qualities; every fragment of the material was used to create domestic, medicinal, artisanal, military, and religious tools. Moreover, it had great symbolic value; itztli, as it was called, was formed when lightning struck the earth: it was the synthesis of the celestial and the terrestrial.

Fifth Level: The Obsidian Winds

Continuing along the journey, the dead arrived at a frozen region with strong winds. These currents were essential for the travelers to throw away all their belongings, such as clothes, jewels, weapons, and personal remains. In the first part of this place, called Itzehecayan, the winds were so strong that they lifted the obsidian stones that cut the corpses. This place was also the residence of Mictlanpachécatl, the god of the cold northern winds, who brought winter from Mictlan to the earth.

Sixth Level: Place Where It Fluttered Like Flags

Beyond Itzehecayan and the home of Mictlanpachécatl began an extensive desert area of difficult movement, including eight wastelands where gravity did not exist. The dead were at the mercy of the winds, which, just when they were about to leave, would return them, carrying them from one side to another like flags, until they finally managed to get out of the path. This can be interpreted as a metaphor: the deceased, by being turned around, detach themselves from the values, customs, and experiences learned in life so that their animistic entity, the teyolia, would arrive at the Mictlan.

Seventh Level: Place Where People Are Pierced By Arrows

Here there was an extensive path on the sides of which invisible hands sent sharp arrows to riddle the corpses of the dead who tried to cross it. The dead had to avoid the arrows so as not to be hurt, bleed out, and be unable to continue the journey. It was also the dwelling place of the god Temiminatecuhtli, the lord of the archers and guardian of the sixth level of Mictlan, the Temiminaloyan. He had hundreds of helpers who were in charge of collecting all the missed arrows and darts wasted in wars, to later use them in the underworld to shoot at the dead while they traveled through his domains.

Eighth Level: Where the Hearts Of People Are Consumed

This was the last level before the body decomposed and separated from the teyolia soul entity, which would later be deposited in Mictlan. This was the dwelling place of an enormous jaguar that devoured hearts. It is important to note that the jaguar had great significance, as it was considered the lord of animals, in the same way that a ruler was for men, so it was highly associated with power and authority. Its strength, ferocity, and agility made it an emblem of royalty. Moreover, for its bravery and pride, it also served as a model and warrior ideal; the image of this animal appears represented in codices in contexts of combat and sacrifice.

Ninth Level: Mictlan’s Final Destination

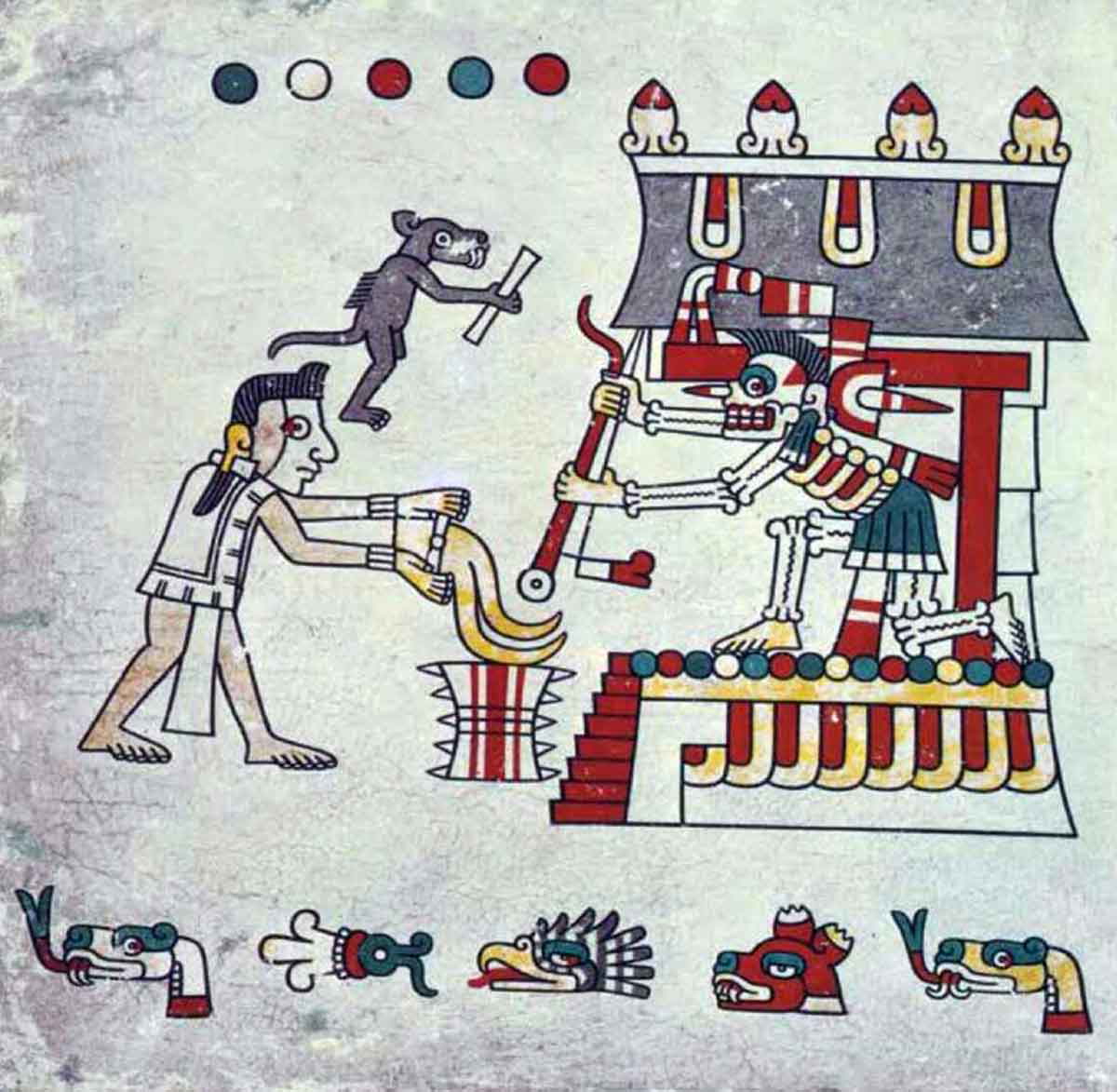

Finally, after four years of travel, the final dwelling place is reached, the place of eternal rest for the souls, the house of the gods Mictlantecuhtli and Mictlancihuatl, who represented the culmination of the vital process. This place was characterized by the fetid air, putrefaction, cold, and humidity, but these were also the symbolic characteristics of the transformation of the body and the separation of the soul. In this place, the body decomposes, and the teyolia, the vital essence, separates to return to the earth.

For the Mexica, Mictlantecuhtli, the lord of the place of the dead, was commonly represented as a skull with many teeth, retaining its eyeballs. He was also associated with animals like the bat, the spider, and the owl, as they were considered omens of death. However, no matter how eerie it may seem, he was not a feared figure; rather, he inspired respect.

Mictlan should not be understood as a moral punishment, similar to the Christian hell, where one goes to pay for sins in life. Rather, it should be understood as the culmination of a natural debt, where the human being who, during life, consumed the resources of the Earth, feeds that same Earth in death, reintegrating him into the vital cycle.