It is not uncommon to hear the claim that the Vikings practiced human sacrifice, and evidence supports that the practice existed. But how prevalent was it among the ancient warriors, and in what situations was it considered appropriate or desirable? This article will discuss the literary, visual, and archaeological evidence for the practice of human sacrifice among the Vikings.

Sacrifices to the Gods

It is important to remember that the Vikings were not a unified people who followed a single religious canon. They were divided into many groups, identifying with their local tribe led by a local chief. It took centuries for them to form into the larger nations that we are familiar with today. The people we call Vikings—people from Scandinavia who also settled in other parts of Europe such as Iceland, Greenland, England, and Russia—shared language, cultural practices, and religious beliefs, but it is important to note that they were not a homogenous people. What happened in one place may not have happened in another.

That said, religious rituals in many ancient pagan cultures involved blood sacrifices, usually of animals. We know that the Vikings made animal sacrifices to their gods from several sources. The best description probably comes from the Saga of Hakon the Good, written by Snorri Sturluson in the early 13th century.

He explains how an earl named Sigurd was known for being diligent in his sacrifices and always presided over sacrifices at festivals. He says that during festivals, the people of the area would come together and bring with them animals, such as cattle and horses, for sacrifice. The animals were killed, their blood let, and collected in special vessels. Brushes were then used to sprinkle the blood over the altar and temple walls. The meat from the animals was used in the festival feast, with modest portions offered to the gods (Saga of Hakon the Good, 16).

While this passage makes no mention of human sacrifice, that does not mean that it did not take place. However, it does probably indicate that human sacrifice was a relatively rare phenomenon, reserved for special occasions or circumstances.

Human Sacrifices to Odin

The Romans, no strangers to animal sacrifice, recorded that the Germanic tribes they encountered, considered ancestors of the Vikings, made human sacrifices to their chief god. The historian Tacitus, writing in the 1st century CE, calls this principal god Mercury, using the name of a familiar Roman god to identify Odin. Tacitus implies that he is the only god who demands human sacrifices, suggesting that the other chief gods, Thor identified as Hercules, and Tyr identified as Mars, accepted more usual sacrifices.

Later accounts also suggest that human sacrifice took place on certain occasions during the Viking Age. The German bishop Thietmar Merseburg, writing between 908 and 1018, records that Vikings met at Lejre in Zeeland every nine years in January and sacrificed 99 humans to the gods, alongside an equal number of horses, dogs, and hens or hawks.

This story is matched by another Christian author, a monk called Adam of Bremen, writing in 1072. He records a similar tradition at Gammel Uppsala in Sweden, where there was a temple of Thor, Odin, and Freyr. He said that they met every nine years to ensure the goodwill of the gods by sacrificing nine males of all kinds, including dogs, horses, and humans. They were all hung from trees around the sanctuary grove.

Both of these authors were Christians reporting on things that they had heard that the “barbaric” Vikings did, and not things that they had seen themselves. But elements of their accounts ring true. The number nine was sacred to the Vikings and appeared in many of their myths. Hanging victims from trees also seems to be a likely ritual. Odin famously hung himself from the world tree Yggdrasil for nine days and nights while pierced by his own spear to learn the secrets of the runes, which he then shared with mankind.

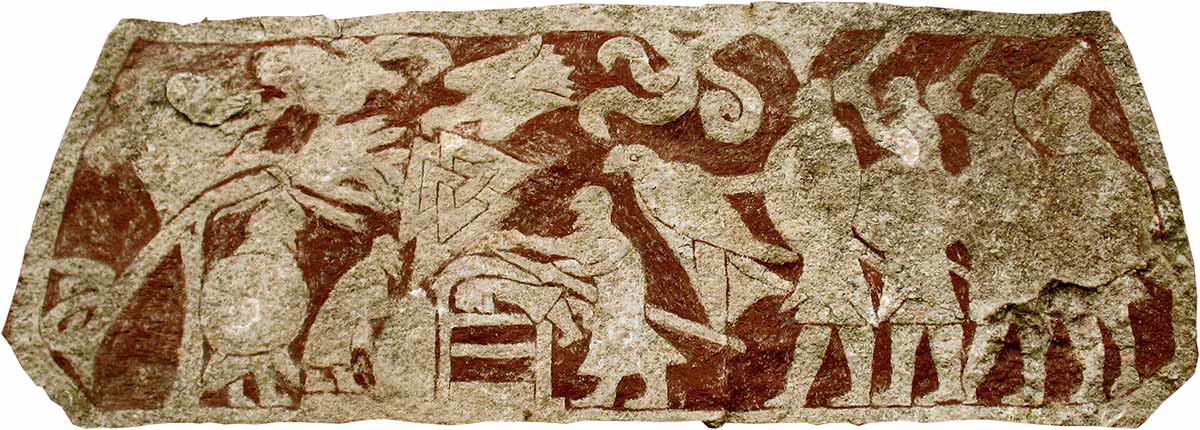

One of the Stora Hammars runestones from Sweden, probably dating to the 7th century CE, also appears to depict such a scene. In the middle, it shows a person who appears to be being sacrificed on an altar. Overhead, there is a large bird of prey, assumed to be a raven, a bird sacred to Odin. To the left is another person who appears to have a noose around their neck and is hanging from a tree. If this is a scene of human sacrifice, it aligns closely with the above stories.

Nevertheless, both of these accounts are often taken with a grain of salt because they are also full of Christian criticism of the practice. While Adam of Bremen acknowledges that the purpose of the ritual was purification, he also describes the bodies as hanging “promiscuously” and refers to the gods as “demons.” Reading through cultural perspective is always a challenge when analyzing comments made by members of one culture about another.

Human Sacrifice in the Sagas

While the descriptions are less detailed, there are also references to human sacrifice in the Norse sagas, mostly written by Christian Vikings after conversion, but drawing on older Norse texts.

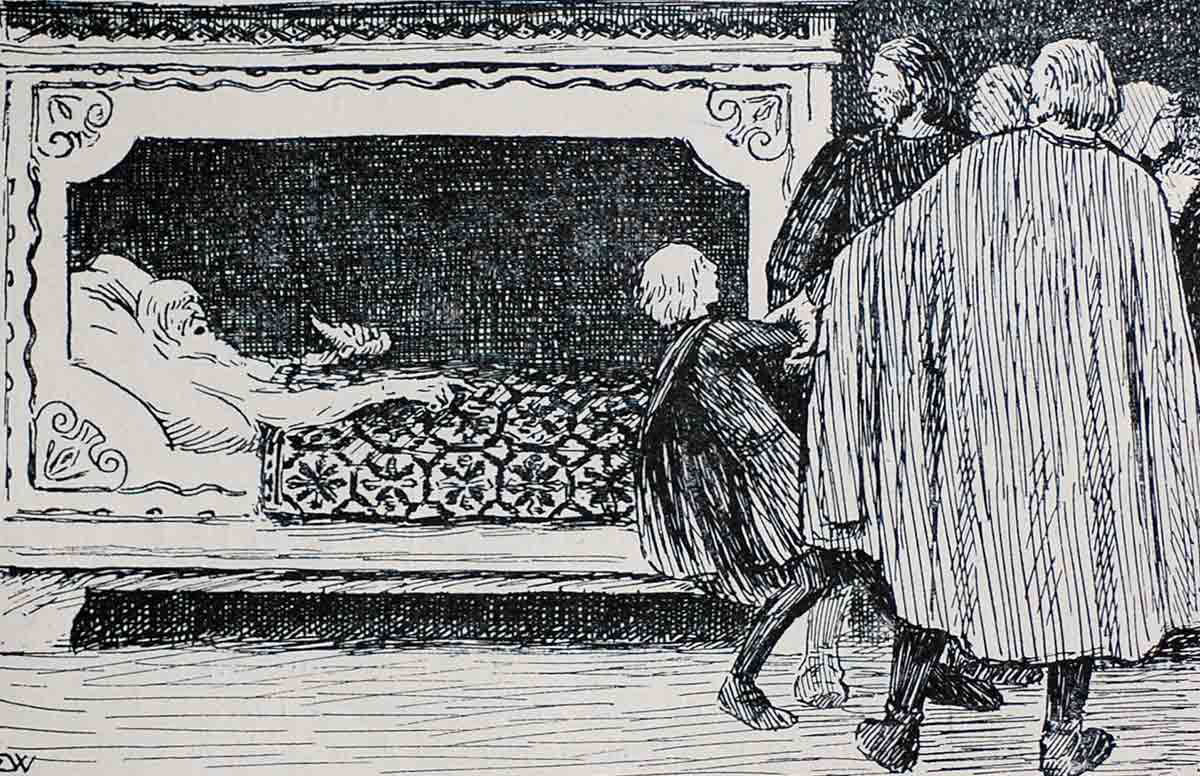

The Heimskingla, written in the early 13th century, records how King Aun of Sweden, when he was 60 years old, went to Uppsala and sacrificed his son to Odin, and in return, he would live for another 60 years. He then returned to Uppsala and sacrificed another one of his sons. He was told by Odin that he would receive another ten years for every son he sacrificed. He continued making the sacrifices even when he could no longer walk and was eventually bedbound. When he had sacrificed nine sons and still had one remaining, the Swedes would not let him make the final sacrifice because it was his time to die. While this is a fanciful but grizzly story, it seems to confirm an association between Odin and human sacrifice.

In the Ynglinga Saga, we meet the Swedish King Domalde, whose lands were suffering from bad harvests and starvation. Initially, the people sacrificed oxen at the temple at Uppsala, but nothing improved. The next year they sacrificed men, but the harvest was even worse. In the third year, they decide to sacrifice the king himself and sprinkle his blood on the statues of the gods. Good harvests returned to the people, and the region was prosperous during the reign of his son. The Historiae Norwegiae verifies this story and adds the detail that he was hanged, like many of the victims in other stories.

This tradition of making human sacrifices in times of dire need may also be preserved in a Swedish fairytale. It recalls an epidemic that killed thousands of people and saw the churches abandoned. To stop the plague, they first buried a cock alive, and then a goat, to no avail. In the end, they buried a poor young boy alive in a grave, but the storyteller is not sure whether this had the desired effect.

Evidence of this type of practice may also be preserved in the archaeological record. At Trelleborg in West Zealand, a Viking Age sacrificial site has been found, predating the fortress built there in 980/1. Human and animal bones, along with jewelry and other tools, were found in five wells, each around three meters deep. There were five human victims, four of them aged between four and seven. A small enclosure was also found nearby, which may have been used for the ritual preparation of the victims. This seems to parallel the story of the poor Swedish boy.

It also seems significant that the victims were interred in wells, which were sacred to the Vikings. The world tree Yggdrasil was believed to be fed by three wells, the boiling well, the well of fate, and the well of wisdom. Odin plucked out his own eye as a sacrifice to drink from the well of wisdom. Therefore, a well may have been considered a very fitting place for human sacrifice.

Human Sacrifice Observed as Funerary Rituals

In addition to the context of sacrifices to the gods, human sacrifice is also mentioned among the Vikings in relation to funerary practices. It is suggested that slaves, who were common in the Viking world, were often sacrificed and buried alongside their masters when they died.

The principal evidence comes from an Arab scholar and traveler called Ibn Fadlan, who was traveling in the early 10th century. He met a group of Rus, who were closely related to the Swedish Vikings, living on the Volga River. He recalls witnessing the funerary rituals for a dead chief, which involved the sacrifice of a slave girl to be burned beside him.

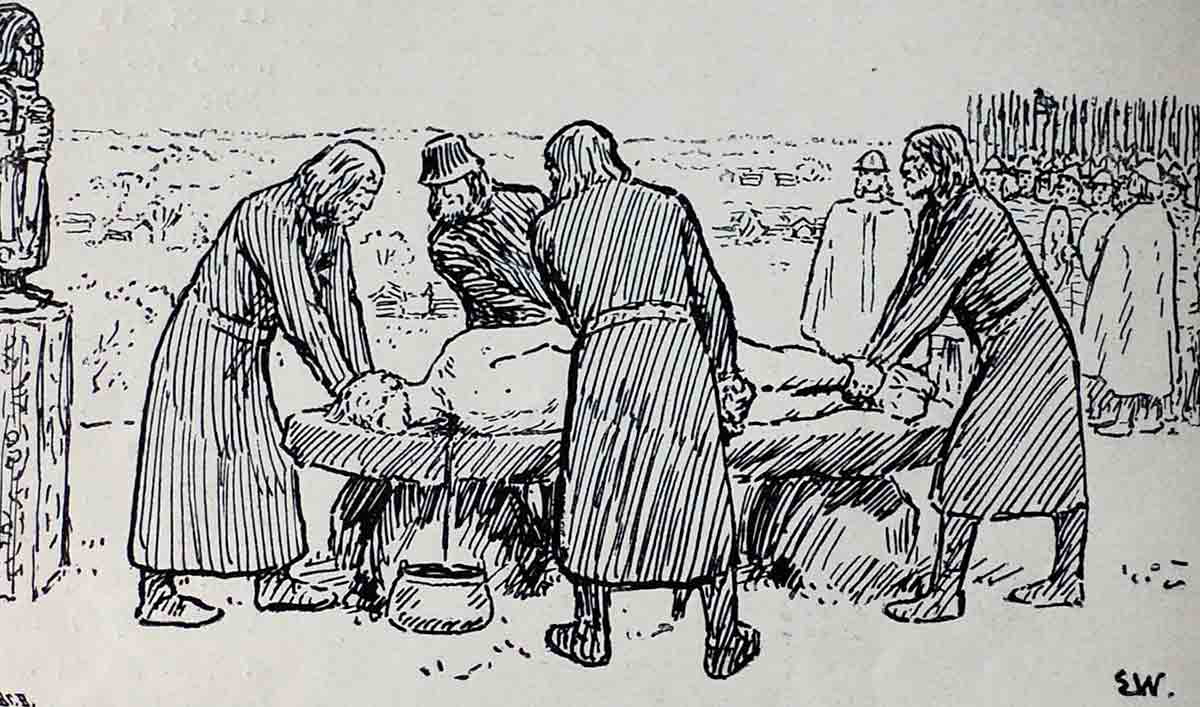

He describes rituals to prepare the girl, which included giving her intoxicating drinks and being raped by six men. He then says that four men held her down by her hands and feet next to the body of the dead chief. The presiding priestess, known as the “Angel of Death,” then wrapped a cord around her neck and gave the ends to another two men. She then proceeded to stab the girl in the ribs with a knife while they strangled her until she was dead. She was then burned on the funeral pyre alongside her master.

While this is a graphic firsthand account, on their own, the exact details cannot be trusted to be completely accurate. As an outsider, it is highly likely that Ibn Fadlan did not understand everything he saw, and he may also have had his own reasons to make the people he encountered seem “other” and “barbaric.” At the very end of the section discussing this ritual, he says that one of the Rus called the Arabs “fools” for burying rather than burning their dead, which again highlights this “otherness.”

Human Sacrifices as Burial Goods

The Norse sagas preserve stories of people choosing to die on the funeral pyres of their loved ones. When the god Balder died, his wife Nanna reportedly threw herself on his funeral pyre to join him. Similarly, in the Lay of Sigurd, when Brunhild caused the death of her love Sigurd, she said to ensure that his funeral pyre was big enough for the two of them. She also made other comments about the preparation of the pyre, including that slaves should be killed, with two placed at the feet of the dead man and two placed at his head.

There is also evidence of this type of human sacrifice in the archaeological record. There are many examples of more than one body in a grave, such as the famous Oseberg ship burial that contained the bodies of two women. These may be examples of master and slave burials. However, there are also a few specific examples that seem to provide more concrete evidence.

For example, a burial from the Vendel Era, just before the Viking Era between 550 and 800 CE, at Birka in Sweden is known as Elk Man. It is the grave of an older man buried with a spear, shield, arrows, and an elk antler next to him. Next to and partly on top of him is the skeleton of a decapitated younger man in a contorted position with his head next to him and no personal objects.

Another grave discovered at Bollstanas in Sweden contains two decapitated men buried belly down with no significant materials. They are buried on top of a layer of burned material rich with burial goods and the body of a third man.

At Flakstad in Norway, the remains of ten people have been found in multiple graves, and three of the bodies were decapitated. Analysis suggests differences between the decapitated individuals and the other people buried there. Analysis of carbon and nitrogen isotopes suggests that the decapitated individuals lived mainly on a diet of seafood, while the rest had a diet richer in land-based proteins such as meat and dairy products. This suggests a difference in social status between the different groups and could indicate slaves buried alongside their masters.

Placing individuals in the ground alongside other dead may have made sense in the Viking context. According to Odin’s Law, anything burned on a funeral pyre or personally placed into the ground could be taken into the afterlife (Ynglinga saga, 8). This is why burial goods were common in graves, as they were things that a person could use in the next life. It may have been believed that slaves could continue to serve. In addition, since the Vikings believed that only great warriors could make it to Valhalla, being buried with a great chief may sometimes have been an attractive prospect, as they could take you to Valhalla with them.