Shaped by a flurry of influences, including Greek, Roman, Arab, Norman, and Spanish, Sicily has long been one of the most contested lands in the Mediterranean. That history is visible and palpable everywhere, from the island’s crumbling temples to its glittering cathedrals and the bustling markets selling foods not found anywhere else in Italy. Each empire left snippets of itself behind, embedded in the landscape and carried on by its people. To explore Sicily is to travel through centuries of cultural exchange shaped by geography and the powers that fought to control it.

When Geography Dictates History

If history has taught us anything, it is that any land “between” empires is destined to be fervently contested. And so it was with Sicily, whose history proves to be no accident. Centrally located in the heart of the Mediterranean, the island became a natural hub for seafaring routes that connected the ancient world. Looking at a map, it is easy to see how ships could sail toward the Greek mainland, the Levant, North Africa, or the Italian peninsula from one central location. Yet Sicily did not just control important maritime choke points; it also boasted fertile plains that were prime for agriculture. Because of that, it became a highly coveted prize for any power seeking dominance in the region.

And emperors were not the only ones seeking fortune here. Sicily offered traders convenient ports that linked markets across continents, so it eventually attracted migrants and exiles alike. They came from every corner of the Mediterranean: from the shores of modern-day Lebanon and Syria to Tunisia, Morocco, and Spain. Some arrived by choice, others by force, each new wave adding to the island’s evolving identity.

How the First Powers Shaped Sicily’s Coasts

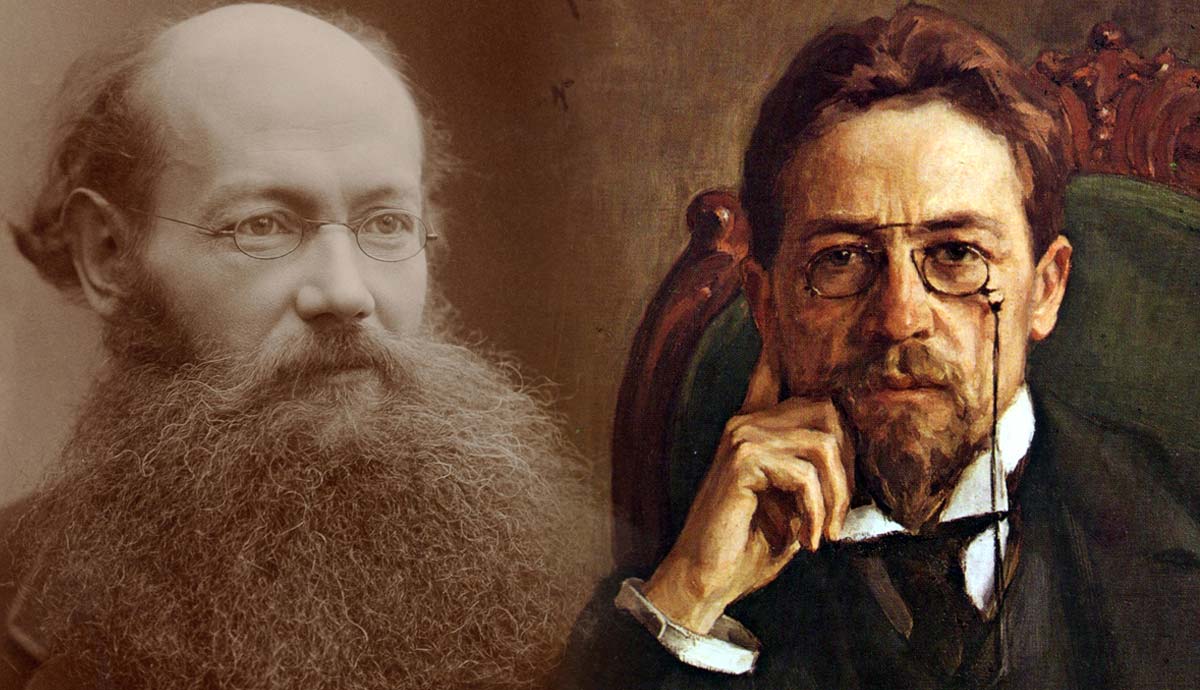

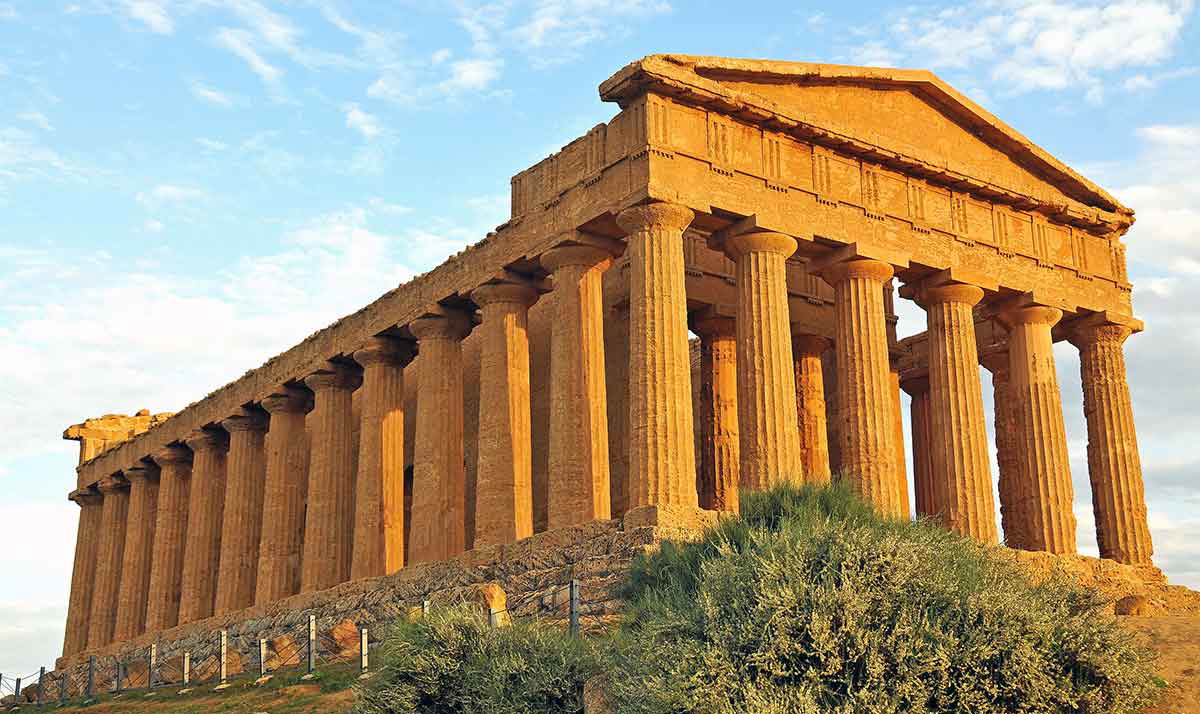

The first major powers to stake a claim in Sicily were the Phoenicians and the Greeks. Skilled sailors from modern-day Lebanon and Syria, the Phoenicians settled in the west around the 9th century BCE, founding places like Motya and Panormus, now Palermo. Not long after, Greek colonists arrived and established cities such as Naxos, Catania, and Syracuse.

The two seafaring cultures arrived with more than ships and ambition. They also brought language, beliefs, architecture, and ideas that took root in Sicilian soil and shaped the island for generations. At first, the Phoenician and Greek “worlds” barely overlapped, yet as their settlements grew, so did the rivalry. Carthage, a rising Phoenician power, and Syracuse, the jewel of Greek Sicily, became bitter opponents, frequently clashing over control.

Sicily didn’t resist or choose sides. It simply absorbed everything.

Syracuse would become one of the most important cities in the Greek world, known for its thinkers, builders, and mighty rulers. The Phoenician heritage, by contrast, was not quite as long-lasting. Traces remain in sites like Motya, but their influence feels more archaeological than cultural. Reasons for this abound. Firstly, the Phoenicians landed in Sicily with trade on their mind, not expansion. They built fewer and much smaller settlements than the Greeks, and used less durable material, so little has endured above ground.

Moreover, when the Romans arrived, they built directly on what the Greeks had started, absorbing their language and architecture. For all these reasons, Greek influence in Sicily enjoyed a continuity unlike the Phoenician influence.

Sicily Becomes the Breadbasket of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic, the predecessor of the Roman Empire, seized Sicily from the Phoenicians during the First Punic War. The Romans set their sights on Sicily more for practicality than prestige, since they needed new fertile plains to produce enormous quantities of grain to feed their growing capital, Rome, across the sea. Roman estates soon spread across the countryside, and with them came roads, aqueducts, and administrative control.

As we now know, the Romans, ever the pragmatic expansionists, built upon what was already there. Greek cities remained active, their culture still very dominant in the east. Sicily functioned as a bilingual province for generations, where Greek and Latin coexisted, and Roman governance rested on older Hellenistic foundations.

Nowhere is this layering more vivid than at the Villa Romana del Casale. Likely owned by an influential Roman aristocrat, the villa is famous for its spectacular mosaics, with sprawling floor scenes that cover entire rooms. The scenes captured here reflect the rhythms of elite Roman life in the provinces: hunting expeditions, banquets, chariot races, and myths, all rendered in astonishing detail.

Arab Control Ushers in Sicily’s Golden Age

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, Sicily passed from Roman to Byzantine control, continuing its connection to the eastern half of the empire. That chapter lasted until the 9th century, when Arab forces from North Africa arrived and took the island in a sweeping conquest.

What followed was a period of incredible cultural flourishing, one that is often lamentably overlooked in Western textbooks. The Arab rulers brought new crops, irrigation systems, and administrative reforms. They were also the ones to introduce citrus fruits, sugarcane, and cotton to the island, transforming its economy and cuisine in the most lasting fashion. Sicilian blood oranges are among the island’s most iconic crops. If not for the Arabs, they might never have taken root here.

Palermo, in particular, became a center of learning, poetry, and architectural creativity. Arabic became the language of administration, while Christians, Jews, and Muslims coexisted, for the most part, peacefully. Though conflict often flared, this golden period left behind a distinctive legacy that still shapes Sicilian identity, perhaps more than any other.

Some of the Arab-era infrastructure survived and was later adapted by the Normans. Remnants of this period are found in the markets of Palermo. Not just in their layout, but also in their flavor. Famous Sicilian dishes like arancini and cassata are delicious reminders of the heritage born of this cultural blending.

Here Come the Normans

The arrival of the Normans in the 11th century marked another sharp shift in Sicily’s history. Much like the Romans before them, the Normans absorbed what was there, keeping Arabic administrators and Greek traditions, building churches that reflected all three worlds.

This is most evident in Sicily’s Arab-Norman architecture, a style that is unique to the island. The Palatine Chapel in Palermo is a picture-book example. Its walls shimmer with Byzantine mosaics, while its ceilings feature Islamic-style muqarnas woodwork. You will find inscriptions in Latin, Greek, and Arabic throughout.

From Devastation to Rebirth Under Spanish Rule

Fast-forward to more recent times and we see Sicily suffer a cataclysmic event that would irrevocably alter its historic course. In 1693, one of the most powerful earthquakes to shake the island ravaged its southern regions. The devastation was catastrophic and widespread: dozens of cities were leveled to the ground, and tens of thousands died. The overwhelming extent of the damage led to a full-scale rebuilding effort. Yet the Spanish, who had been ruling over the island since the late Middle Ages, took the chance to start afresh. Cities like Noto, Ragusa, and Modica were rebuilt in the Baroque style that was popular across Europe at the time.

With their wide staircases, grand piazzas, and ornate churches, these new towns looked nothing like their medieval predecessors. Today, they form part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site and stand out as some of the most distinctive Baroque cities in Europe.

Few places in Europe claim the kind of complicated and colorful history that Sicily does. The legacies of conquest, migration, and exchange are still visible just about anywhere you go. From the dialects spoken to the ingredients used in cooking, the layout of old towns, and the multiple levels of religious architecture, every aspect of the island reflects a shared history that spans cultures and continents.

If you have ever wondered what thousands of years of cultural exchange can do to a place, visit Sicily and see it for yourself.