Cartography, the science and practice of drawing maps, both reflects and shapes our perception of the world. Over the millennia, many maps have been produced, ranging from basic sketches to detailed manifestations of both science and art. The evolution of the maps we use reflects the evolution of our understanding of our world. Here are five fascinating maps that captured our view of the world at a certain point in time, which also shaped history.

1. Ptolemy’s Geographia (Ptolemy’s World Map)

Not to be confused with Ptolemy I, Alexander the Great’s successor and founder of Egypt’s Ptolemaic dynasty, Claudius Ptolemy was an ancient mathematician, astronomer, and geographer. Born in Alexandria, Egypt, under the rule of the Romans, Ptolemy is believed to have been ethnically Greek or a Hellenized Egyptian. He used both Greek and Babylonian knowledge in his work, which was extensively used or commented upon in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Ptolemy’s world map is a title given to any map based on Ptolemy’s description of the known world of the Greco-Romans in the 2nd century CE in his Geographia. Thus, there are many maps in a variety of styles, but they are all based on Ptolemy’s atlas, originally based on an atlas created by Marinus of Tyre, his geographical dictionary, and his treatise on cartography.

The map depicts three continents: Europe, Asia, and Africa, then known as Libya. For its time, Ptolemy’s world map was greatly detailed and surprisingly accurate. Such was its value that the Roman Empire presumably used it to support its imperial expansion. The Romans traded throughout the Indian Ocean and even reached China.

2. Mapamundi de los Cresques (The Catalan Atlas)

Created almost at the end of the European Middle Ages in 1375, the Catalan Atlas is often considered the most important map of the medieval period. Much like other major cartographic works, the Catalan Atlas was the immediate product of its context. The atlas was created on the island of Majorca, which had a long history of seafaring and trade. Thus, there was a keen interest in perfecting the cartographic craft to aid commerce and navigation. The Majorcan cartographic school was a successful endeavor that rivaled its contemporary counterpart, the Italian cartographic school.

The Catalan Atlas depicts the known world with great detail and incredible artistry. It begins with Catalan texts and illustrations on cosmography, astronomy, and astrology, plus information on the tides and sailing. The rest of the document is the actual map. It depicts Europe, the Far East, North and West Africa, and Jerusalem and its surroundings. The map is both an innovative piece and is conscious of past cartographic traditions and discoveries.

The map includes a particular reference to the legendary ruler of the Mali Empire, Mansa Musa, in the western part of Africa, right at the bottom of the map. He is depicted crowned, sitting on his throne while holding a golden nugget in one hand and a scepter in the other. Mansa Musa is famous for his incredible riches and is believed to be the richest man in history.

3. The Waldsemüller Map (Waldsemüller’s Universalis Cosmographia)

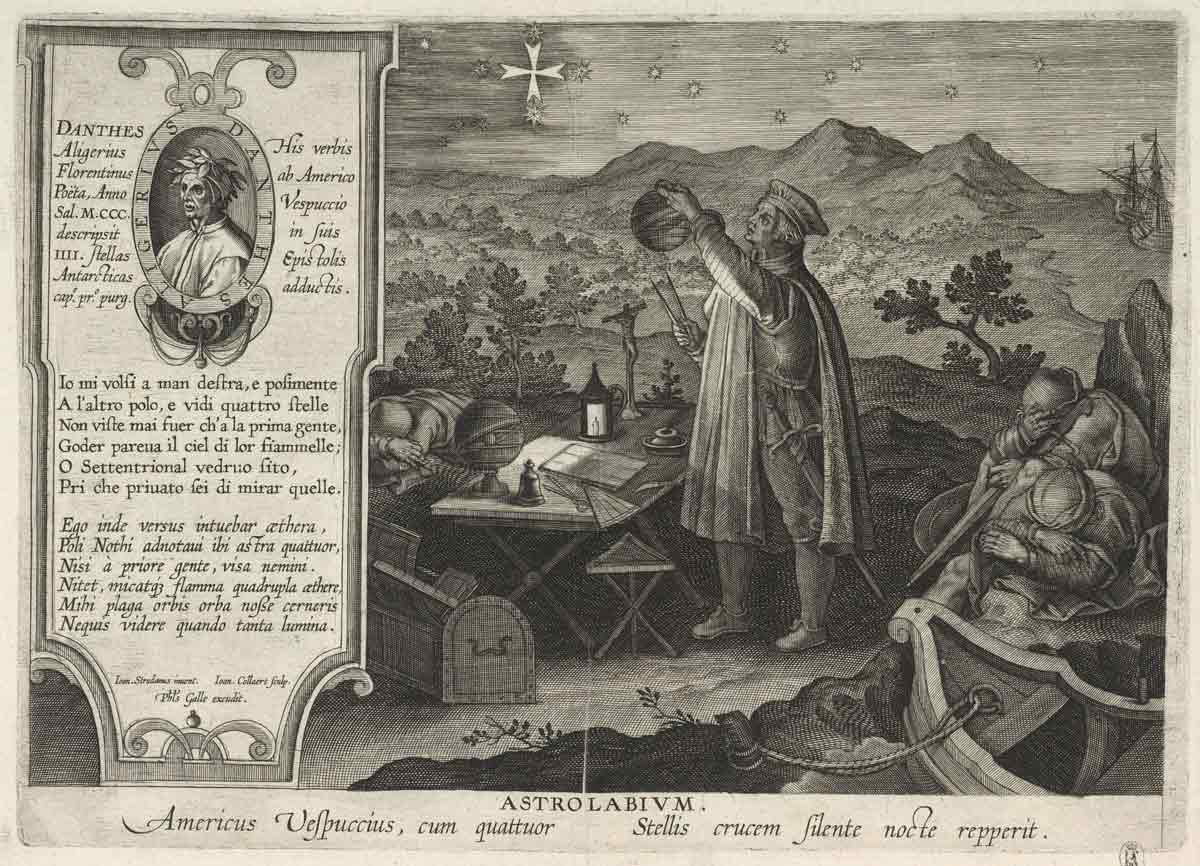

Martin Waldsemüller’s Universalis cosmographia is one of the maps that changed our perspective of the world. Often just called Waldsemüller’s map, Universalis cosmographia is a testament to major changes in understanding the world during the Age of Exploration. Based on the explorations and accounts of Florentine merchant Amerigo Vespucci, the map includes a raw depiction of the Americas and, for the first time, gives the land the name “America.”

Waldsemüller’s map is a mappa mundi that follows the traditions of preceding cartography but adds key new elements that make it a worthy standalone piece. Waldsemüller named the New World in honor of Vespucci, believing him to be the first to define said land as a new, previously unknown continent. However, Vespucci never truly expressed that what he had explored was part of a truly distinct continent. Instead, Christopher Columbus was believed to be the true discoverer, yet he also never thought he had reached a new continent.

Waldsemüller later corrected himself and, on a new version of his map, gave the new continent the title of Terra Incognita. He also recognized Columbus as responsible for the discovery, not Vespucci. Still, Vespucci’s legacy as the bearer of the New World’s name was greater than Columbus’. Replication of the map boosted familiarity with the new name, which aligned well with existing terms (Asia, Europa, Africa), and meant that the name was adopted.

4. The First Atlas (Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum)

Although maybe not as famous as some of the other maps on this list, Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum is considered the first modern atlas. The atlas was first published in 1570, but Ortelius would make changes to it throughout his life, up until his death in 1598. Growing into more than 31 editions in seven languages and more than one hundred maps, Ortelius’ atlas was highly consequential. Decades after Ortelius’ death, Dutch cartographer Willem Blaeu continued Ortelius’ work and created his own atlas. This would reach a final version under the name of Atlas Maior, possibly the largest and most expensive book published in the 17th century.

Both Ortelius’ Atlas and the Atlas Maior are considered masterpieces of Dutch cartography. The Theatrum Orbis Terrarum consisted of a series of uniform map sheets and a supporting text bound, forming a proper book. By the last edition edited by Ortelius himself, the atlas had detailed maps of their known world, including most of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, the Middle East, Russia, China, Southeast Asia, the Americas, and Europe. The atlas was very quickly a successful endeavor, becoming a popular item among the wealthy elites of the time.

In addition to being considered the first true modern atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum is also considered the official beginning of the Dutch Golden Age of Cartography, a period of great cartographic production and innovation. The first atlas, the use of triangulation, and the first atlas of nautical charts were all examples of successful innovation during the Dutch Golden Age. Many famous cartographers, such as Ortelius, Gerardus Mercator, and Johannes Janssonius, enjoyed success during this period.

5. The Mercator Projection (Mercator’s 1569 World Map)

Perhaps the most recognizable map in this list, Gerardus Mercator’s 1569 World Map, set in motion one of the most consequential cartographic traditions in history: the Mercator Projection. Much has been said about this map, but little is known about its creator and its first incarnation. For starters, the Mercator projection isn’t a map per se but rather a projection.

Instead of just being a standalone map, a projection is a cartographic element that precedes any two-dimensional map. Given that the world is spherical, the translation from a three-dimensional representation into a two-dimensional one requires certain transformations. These transformations are nothing more than decisions taken to portray the world in a particular manner. Mercator’s 1569 World Map, with its incredibly long complete title, “New and more complete representation of the terrestrial globe properly adapted for use in navigation,” is the first map created from this type of projection. The projection is known for inflating the size of objects away from the equator, making certain landmasses like Greenland appear much larger than they truly are.

The Mercator projection is somewhat infamous for its arguably exaggerated distortion. All three-dimensional objects will have some sort of distortion when represented on a plane. Yet the Mercator projection has been accused of being unsuitable for general world maps, biased towards the northern hemisphere, and responsible for influencing people’s worldviews. Mercator originally devised the projection to provide a uniquely favorable perspective for navigation, which it did successfully. Still, the criticisms towards the projection remain valid; its overall dominance in the 19th and 20th centuries made it difficult to escape the particular perspective provided by the projection.