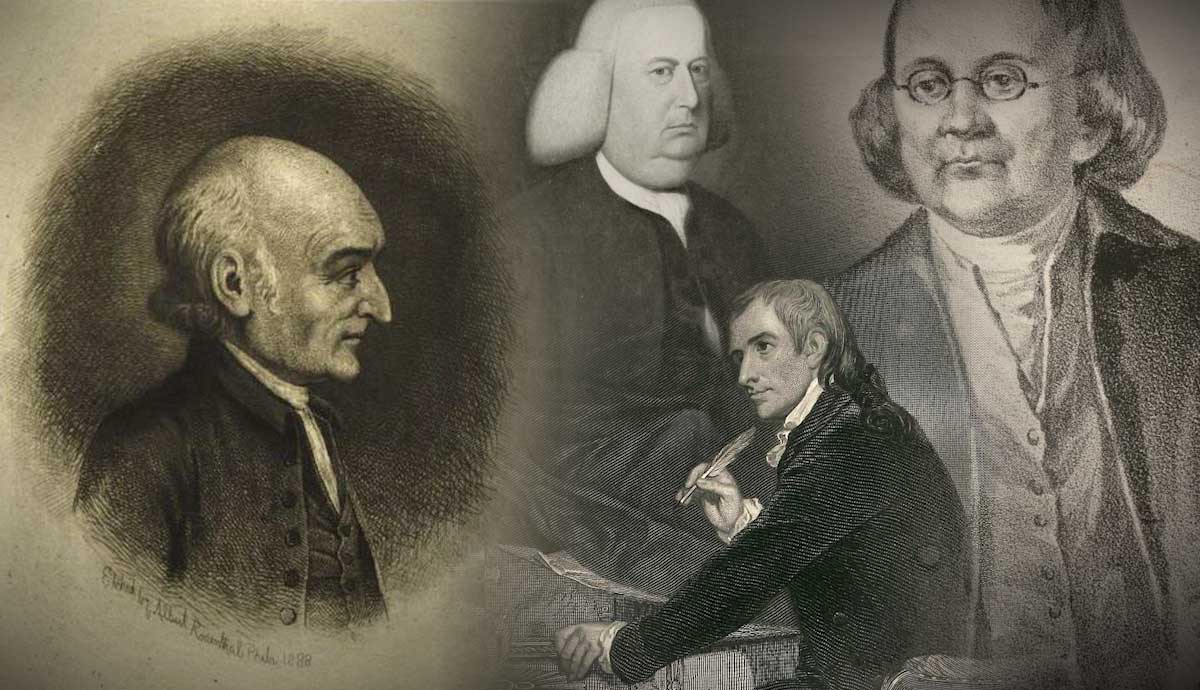

The American Revolution uncovered many determined and dedicated colonists ready to help the colonies break away from Britain. From soldiers to politicians to influential rabble-rousers, there was no shortage of colonists ready to sacrifice their lives for the chance to gain freedom from the Tyranny of King George in Great Britain. Here are four more of the lesser-known founding fathers who signed the Declaration of Independence.

1. Francis Hopkinson – New Jersey

Hopkinson was born to a judge from London named Thomas Hopkinson and his wife Mary, a native of Philadelphia. Francis was a smart and artistic young man, becoming the first graduate of the Academy of Philadelphia in 1757 at the age of 20. Hopkinson’s artistic talents were plentiful, and he flourished in the arts at a young age. He was a musician, composer, author, poet, artist, and inventor–even learning to play the harpsichord at age 17. He studied art under the famous British-American artist Benjamin West and was described as a talented painter by John Adams.

After the loss of his father in his teen years, Francis began to look up to Benjamin Franklin, a close family friend, as a mentor and a role model. And while Francis could have had a successful career serving the crown, Franklin convinced him otherwise. Instead, he joined the Patriot cause in the mid-1770s and, as a result, was elected to the Second Continental Congress as a delegate of New Jersey in June 1776. He served on the Continental Marine Committee before leaving Congress to head the Continental Navy. During this time, he was also chosen to design the Great Seal of New Jersey. In 1778, he was named the Treasurer of the Loans for the newly formed US as well as a judge of the Admiralty Court of Pennsylvania. Soon after, he helped to ratify the Constitution in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and was appointed by President Washington to be the first federal judge of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania in 1789. Shortly thereafter, Hopkinson was chosen as a consultant on the Second Committee on the Great Seal of the United States.

While Hopkinson was serving as a consultant to the second US Great Seal Committee in the spring of 1780, the Continental Admiralty Board accepted a seal that he had designed for them, whereupon Hopkinson wrote the board a letter seeking compensation for flag and seal designs, among other services. His requested payment: a quarter cask, or about 28 gallons, of “the public wine” (See Further Reading: Smith, 2022).

Ultimately, Francis Hopkinson would bill Congress three additional times for the Flag in 1780, which he called the Naval flag of the United States. This flag had more red stripes for visibility and became the preferred national flag, according to historian Earl P. Williams Jr., who wrote his dissertation, and eventually a biography, on Francis Hopkinson.

Yet, most do not know of his role in the creation of the American flag due to many of his historical papers being hidden away within the Library of Congress books and documents. When Williams Jr. located them in 1917, he wrote a biography on Hopkinson; however, few copies were made, leaving his role largely unknown to most Americans. Thanks to his fifth great-granddaughter, Sarah Jenkins Smith, a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution Chapter in Maryland, much of the information was able to be retrieved and shared.

2. Philip Livingston – New York

Philip was born into a well-to-do family from Albany and graduated from Yale in 1737, becoming a merchant. In 1754, he attended the Colonial Convention in Albany and helped organize the New York Public Library. During this time, he also was one of the founders of Kings College, which eventually became Columbia University. He was a fervent promoter of higher education.

Shortly thereafter, Livingston was elected to the New York House of Representatives. Philip continued to grow into an important political figure, representing New York at the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, the precursor to the American Revolution. When New York established a rebel government in 1775, Livingston became the President of the Provincial Convention and a delegate to the Continental Congress. He strongly supported separation from Britain and remained active as a promoter of efforts to fund and raise troops for the War of Independence.

Philip, known as “Philip the Signer,” was one of three Livingstons to serve as members of the Continental Congress. Although Philip was the only one to sign the Declaration of Independence, his brother William, an attorney and future first governor of New Jersey, and his first cousin Robert R. Livingston, who later became the chancellor of New York, were both active contributors during the sessions of the Continental Congress.

During the Revolution, Philip’s youngest son, Henry Philip Livingston, served as a captain in George Washington’s Guard. He remained a constant contributor to the Continental Congress even after the Declaration was signed, and concurrently served in the New York State Senate in 1777. Philip died a year later before the Revolution was completed. Thus, he was never able to see the fruits of his labor in the fight for independence.

3. George Wythe – Virginia

George Wythe was an academic and a scholar, educated by a widowed mother, who made a name for himself as a professor at the College of William & Mary. Wythe was known for his lifelong pursuit of virtue, holding his government, particularly the legal system and those who worked within it, to a high moral standard. He studied Enlightenment philosophy, emphasizing reason and individualism. At the school, Wythe taught Greek, Latin, Mathematics, Literature, and Science. He is well known as a legal mentor for Thomas Jefferson, but he also taught and mentored future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall and future President James Monroe.

In 1748, Wythe passed the bar and was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, and then appointed to the office of Attorney General. He helped to create the Virginia State Constitution and sat on a committee with Thomas Jefferson and Edmund Pendleton to review and codify Virginia’s laws. During this time, he also designed the official seal of Virginia, The College of William & Mary’s second official seal, as well as the seal for the High Court Chancery of Virginia.

Wythe attended the first Continental Congress in 1775 and joined fellow Virginians Thomas Jefferson, Richard Henry Lee, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, and Carter Braxton as an official delegate. He was also elected as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention but had to resign from that post due to his wife’s illness. Throughout his political and academic career, he argued publicly and privately against slavery, urging the emancipation of enslaved people.

Strangely, Wythe died in 1806 by apparent poison by his grandnephew, George Wythe Sweeney, who was boarding with him. It is believed that he and his household staff were poisoned with arsenic placed in the coffee they drank. Sweeney would face trial for murder as well as for check forgery after he was caught cashing forged checks on George Wythe’s accounts. Yet he was acquitted of murder, his forgery conviction was overturned, and he was released a free man. He fled to Tennessee, where he encountered more run-ins with the law before disappearing completely. George Wythe had the last word, though, as his new will disinherited Sweeney.

4. William Ellery – Rhode Island

William Ellery was a smart child. Initially homeschooled by his highly educated father, he attended Harvard College and graduated at the age of 15. He began work as a merchant, customs collector, and then a Clerk for the Rhode Island General Assembly before beginning to practice law in 1770. He was active in the Rhode Island chapter of the Sons of Liberty, stating, “To be ruled by Tories (supporters of England) when you may be ruled by the Sons of Liberty is debasing.”

Due to the sudden death of Samuel Ward, there became a vacancy within the Rhode Island delegates. Ellery was quickly slotted into that role and appointed to the Marine Committee along with many others, later participating in the foreign relations committee as well. While serving as a delegate to the Continental Congress, he also held the office of Supreme Court judge of Rhode Island.

Unfortunately for Ellery, his involvement in the revolutionary cause cost him quite a bit of money. When the British captured Newport in 1778, they sought out Ellery’s home and burned it to the ground. This incident is a reminder of what many of the founders of the US sacrificed in the fight for independence.

Like many of his fellow Continental Congress delegates, Ellery strongly opposed slavery and advocated for abolition. After the Revolution, he was appointed the First Customs Collector for the port of Newport, Rhode Island and served there until his death in 1820 at the age of 92. When he died in 1820, he was only one of three signers to live into their 90s. (John Adams and Charles Carroll of Carrollton were the other two signers). He had outlived two wives, fathered 19 children, and served under five different presidents as a dutiful public servant.

Further Reading:

Smith, S. J. (2022, July/August). American Spirit Magazine. Designer of the Stars and Stripes. The Forgotten Legacy of Francis Hopkinson, pp. 46-48.