The Italian era of the Renaissance gave birth to many outstanding creative figures, yet the most influential quartet of them hardly ever gets disputed. Polymath Leonardo da Vinci, painters and architects Raphael and Michelangelo, and sculptor Donatello formed the visual culture and our contemporary understanding of the era. Read on to learn more about the four greatest figures of the Renaissance.

The Hierarchy of Renaissance Masters: From Raphael to Leonardo

The Renaissance era was a time of great scientific and cultural development, which in many ways defined the trajectory of the Western world for centuries to come. In Italy, it was the era when the most outstanding art was created, generously sponsored not only by the Church but by private patrons and art collectors. Despite thousands of creatives who functioned at that time, four names were and remain specifically important: Donatello, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Leonardo da Vinci.

Of these four great figures, Donatello was the only one who was always appreciated but never achieved truly cult status. Mostly focused on sculpture, he was the least diverse of the four. Still, the status of the four greatest creators was never truly equal, with their importance and reception varying according to the era. The most prominent of them during their lifetimes was Michelangelo, known as The Divine One. However, as the 17th century unfolded, the drama and dynamism of Michelangelo became overwhelming and tiresome, and Raphael’s balanced harmony became the new standard. Admiring Michelangelo for a long time was a marker of avant-garde thinking and unconventional tastes. The 1780 self-portrait of the famous English portraitist Joshua Reynolds included a bust of Michelangelo instead of the expected Raphael. This gesture was interpreted as a provocative proclamation of Reynold’s non-traditional outlook on art.

Leonardo da Vinci was long primarily known as an art theorist and author of scientific treatises rather than an artist. However, in the 20th and 21st centuries, his figure rose to the top, making him the quintessential Western painter. Part of the reason for the formation of the Leonardo cult was the 19th-century era of Romantic literature and art. The Romantic stereotype of a tormented genius who never got to finish any of his ambitious plans proclaimed the superiority of a dream over its realization.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

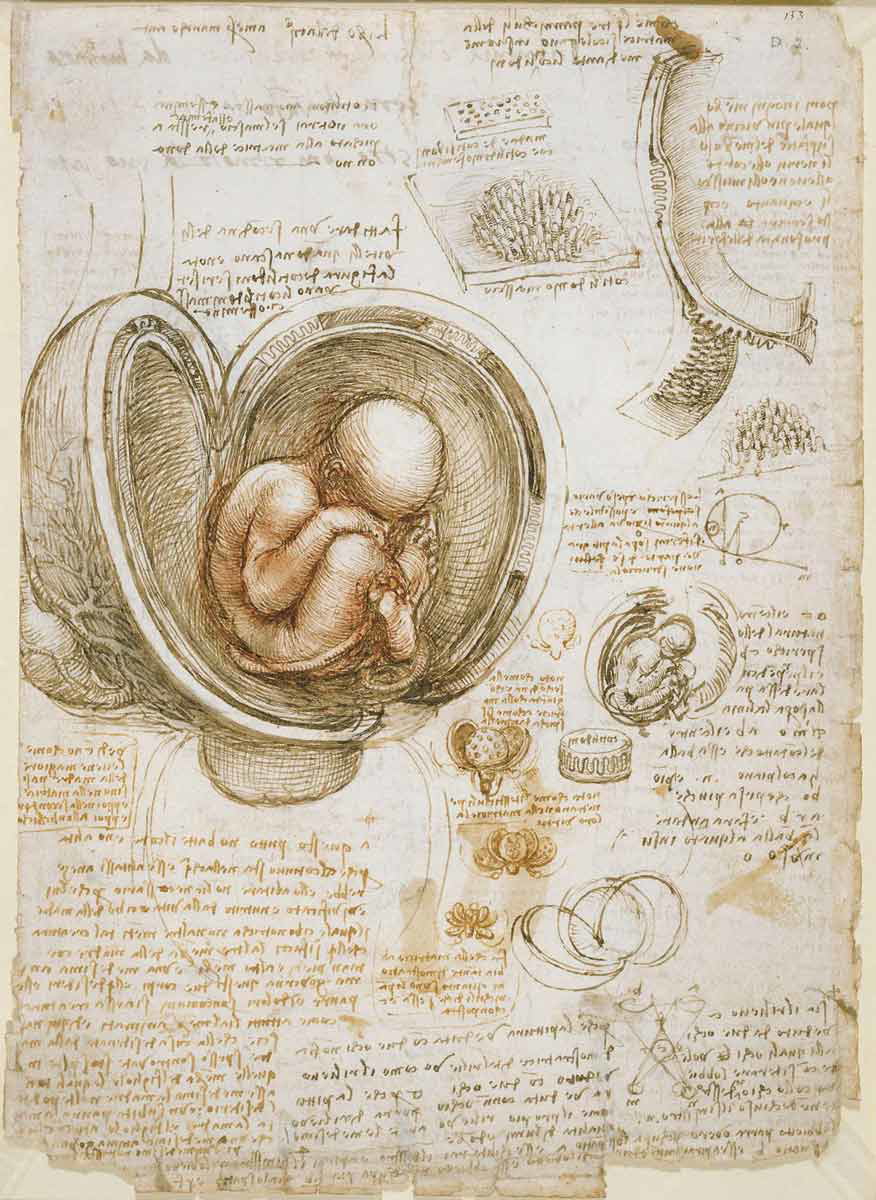

The undisputed hero of the past centuries and possibly one of the most famous artists who ever lived, Leonardo da Vinci still manages to remain mysterious and complex even to those who devote their entire lives to studying his art and notes. He was primarily interested in science rather than in art and let this interest fully consume him during the last years of his career. He designed flying machines and submarines, studied human anatomy and the structure of light, drew maps, and dissected cadavers.

One of Leonardo’s innovations was the transformation of the painted portrait genre into something we are familiar with today. The dominant style of portraits in the 15th century was an image in profile, reminiscent of Ancient Roman reliefs and medals. Such portraits had no intention of recording the model’s unique character and personality but rather aimed at adding them to the pantheon of heroic and respected types. Leonardo da Vinci was the first artist to introduce a new goal and a new structure of portrait painting that would be centered around the model’s individuality.

Moreover, da Vinci’s painted works were incomparably more complex in technical terms than the works of his contemporaries. Almost every portrait by da Vinci included a specific angle or a compositional challenge that required original thinking and a good understanding of perspective, mathematics, and the construction of space.

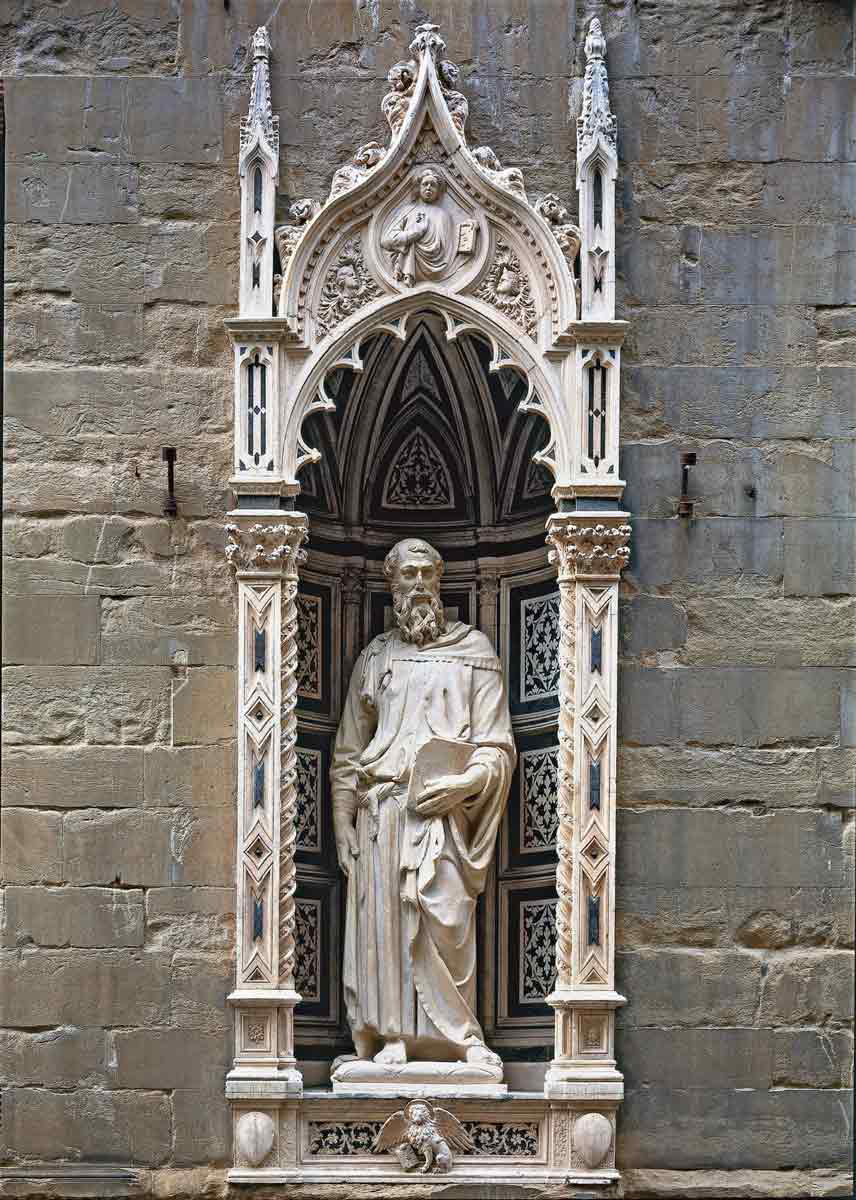

Donatello (c. 1386-1466)

Donatello is often unfairly overlooked in comparison with giants like Michelangelo and Raphael. Unlike them, he focused his efforts only on sculpture, yet he mastered his art way earlier than the others and paved the way for their compositional and narrative innovation. Donatello’s first appearance in public records could hardly hint at the fate of a great artist: in 1401, he was arrested for beating a German named Anichinus Pieri with a stick. Unfortunately, the cause of the conflict remained unspecified. However, only a few years later Donatello would become known as an innovative and daring sculptor. He was one of the first creators not only to become interested in Roman art but also to start excavating it together with his friend Filippo Brunelleschi.

Donatello combined mathematical solutions for artists that originated in his time (such as linear perspective) with styles and realism found in the art of Antiquity. His David, which may seem boring and ordinary to us today, was actually groundbreaking for his time: this was the first freestanding sculpture created since the Roman era. As some contemporary sources stated, Donatello was rather critical of the teachings of the Catholic church and even questioned the existence of God. For that reason, he was probably able to leave the constraints of canonical depictions of saints and Biblical events and invent something innovative.

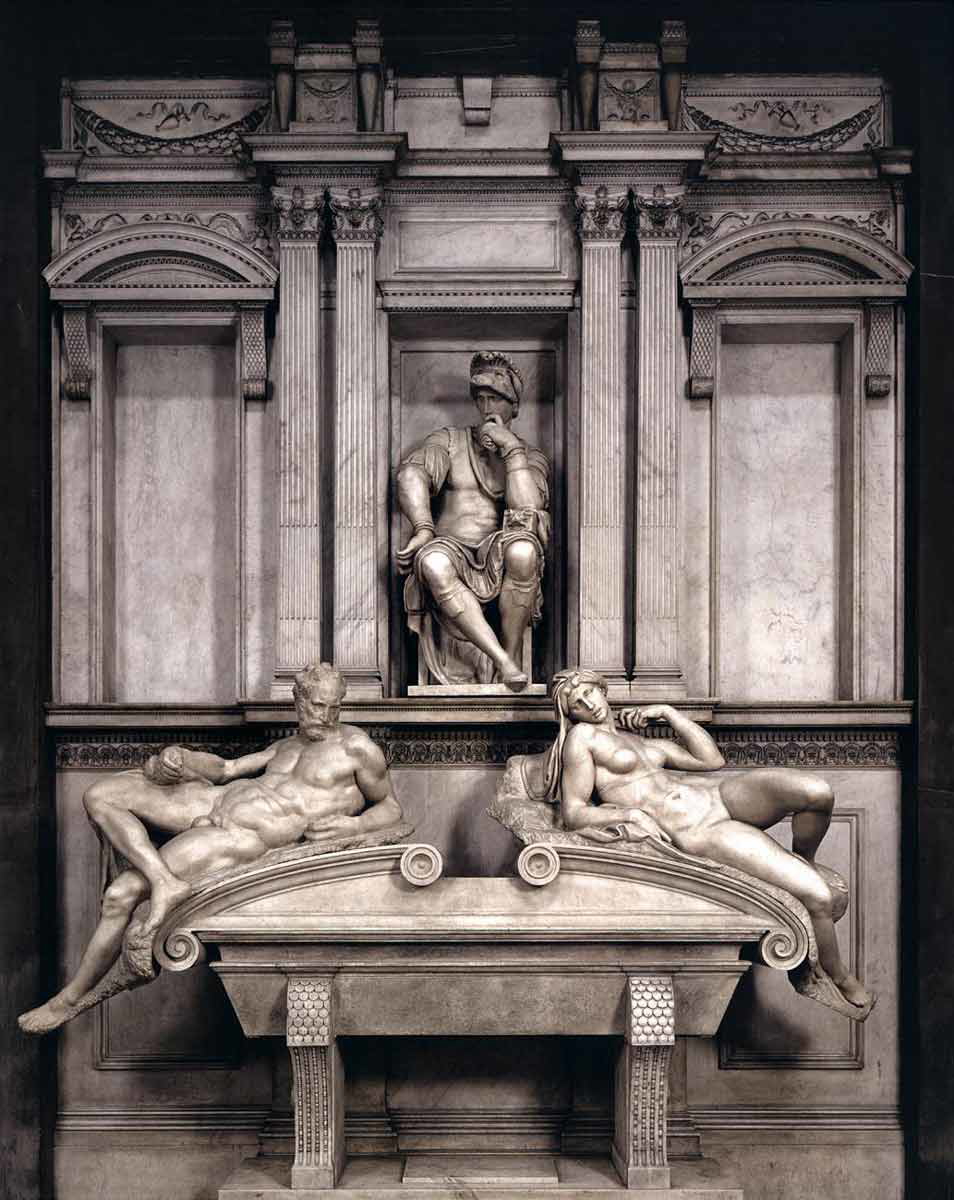

Michelangelo (1475-1564)

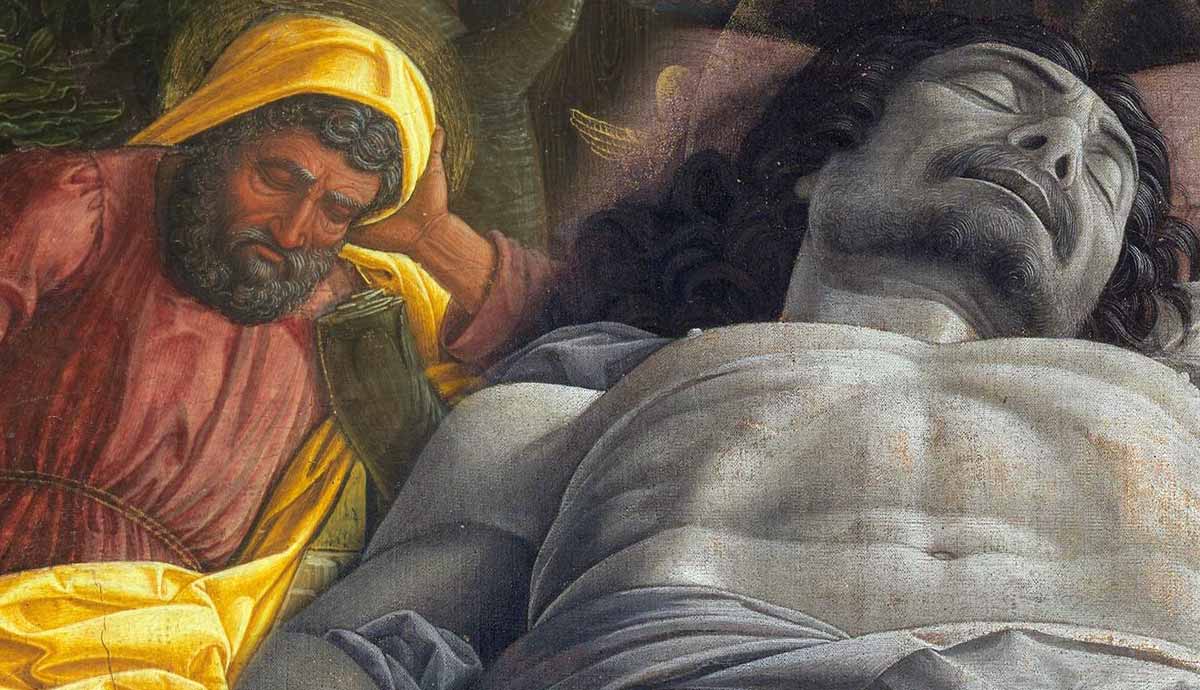

Michelangelo, primarily known as a sculptor, was an extremely gifted architect and one of the most gifted poets of his generation. Unlike Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo did not apply art as a tool for research and studying the world. For him, art and life were emotional expressions, drama, tension, and an endless quest toward a spiritual revelation. His expressive means was the human body in its entirety, and not merely an individualistic portrait or a symbolic landscape.

Compared to most of his contemporaries, Michelangelo lived a remarkably long life of 88 years and kept working until his last days. He was one of the rare artists of his era who saw their biography published during their lifetime. The first edition of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of The Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, which included an entry on Michelangelo, was published in 1550, when the sculptor was still alive and active.

Michelangelo was never supposed to become an artist due to his privileged aristocratic background. However, his family had lost its generational wealth, and his father was forced to temporarily give Michelangelo away to a family of a local stonemason, who taught him to work with clay. Michelangelo’s privileged background was noticeable from the presence of a last name, Buonarroti. In most cases, the artists were known either by nicknames (like the Venetian Canaletto), or by their place of birth, like Leonardo da Vinci (literally translated as Leonardo from Vinci).

Raphael (1483-1520)

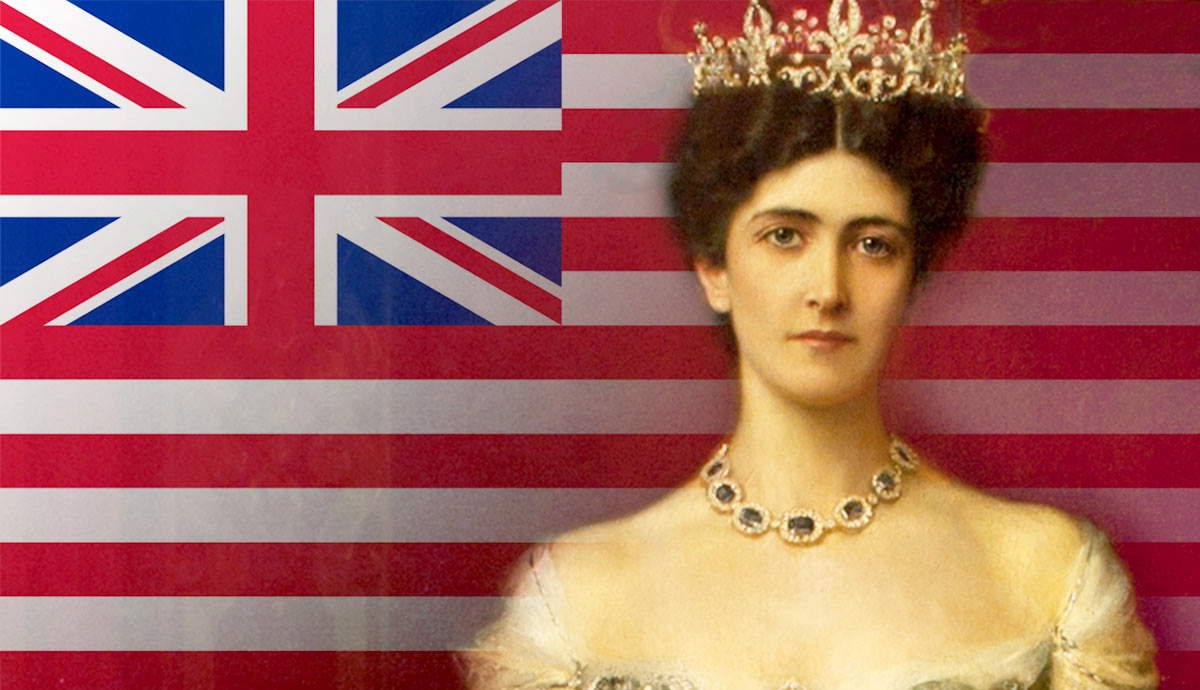

Raphael was the youngest of the four great artists, yet was equally, if not more, influential at several points in history. Born Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, he was the son of a court painter in Urbino, a small yet culturally significant city. From his early childhood, he demonstrated great artistic talent and worked in his father’s workshop. Orphaned at the age of eleven, Raphael entered a workshop of the painter Pietro Perugino. Perugino was an outstanding master and one of the earliest proponents of oil painting in the Italian history of art. With Perugino, Raphael occasionally traveled to Florence, the cultural center of the time, and saw the works of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and other great masters.

Raphael started to work on his own outstandingly early. The earliest surviving contract signed by him and his commissioner indicated that Raphael was only seventeen at the time. However, the complexity of the commission (this was an altarpiece with several figures on it) indicates that Raphael was already an experienced painter with an established reputation. If Michelangelo’s driving force was drama, Raphael’s was the quest for perfect harmony in form, color, composition, and life, all at once.

As a Renaissance artist, Raphael worked in several different domains of art, not limiting himself to painting. He was an architect, a sculptor, a tapestry designer, and a talented poet. In opposition to the brooding and aggressive Michelangelo, he was friendly and charming. The influence of Raphael’s creative harmony and personality extended much further than his lifetime. For centuries, he was the principal role model for European painters. In the 19th century, a group of young artists dissatisfied with their contemporary artistic conventions adopted his name as a sign of protest, becoming known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

The Sistine Chapel: The Most Famous Clash of Renaissance Men

Contrary to the expectations of many historians, Raphael and Michelangelo apparently had no rivalry between them. Both were invited to work by the Pope, and both worked simultaneously in their own manner. They were strikingly different: Michelangelo, with his difficult personality and explosive temper, preferred to stay further from the crowds and work alone. Raphael, a prominent social figure, was always surrounded by friends, assistants, and apprentices and ran an enormous workshop with branches in several locations. Generally, Raphael was not prone to conflict and did not suffer from the presence of other talented painters around him. While Michelangelo was busy painting the chapel’s ceiling, Raphael designed a series of sixteen tapestries, woven from gold and silver threads, to decorate the walls.

Another occasion when the two great Renaissance figures worked together—or, in this particular case, against each other—was the clash between Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. Both artists were in high demand, and both could not stand each other. Nonetheless, the Florentine state asked both artists to paint a battle scene for the town hall Palazzo Vecchio, working next to one another. Neither of them had finished the job. Leonardo made a tragic mistake in the paint formula so the mural peeled off the wall, and Michelangelo was urgently called away on another commission.