Glass is an ancient artistic material, used by artists of all cultures for millennia. Despite its fragility, it managed to preserve quite well, with traditions and artifacts being passed down from generation to generation of artists. Read on to take a look at the long history of glass art and the tradition of glassmaking from the masters of Antiquity to contemporary artists.

Glass Art in Antiquity

Glass is an ancient material that has been used by humans for millennia. Initially, the first contact of mankind with glass-like materials came through volcanic activity. Obsidian, a naturally occurring glass that is essentially a hardened lava, was used by our ancestors as a base material for making sharp tools. In Ancient Egypt, people learned to create glass beads and small objects by melting quartz sand.

The tradition of glassblowing allegedly formed in the 1 century BCE and has developed ever since. In Ancient Rome, masters developed numerous techniques and styles of glassware, launching the widespread tradition and expectations of form and design. The Venetian island of Murano became the center of European glass production in the 13th century after a vast group of Byzantine glassmakers moved their workshop to the island. Even today, Murano glass is valued for its intricate designs and complex technologies, still made by the human hand.

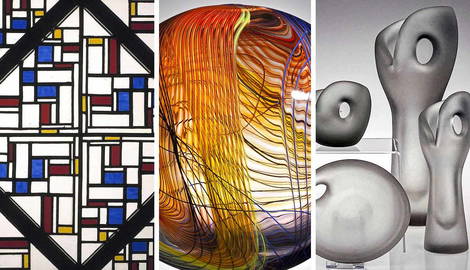

Stained Glass Windows

Perhaps the most stunning and well-remembered form of glass art is stained-glass windows, which were mostly placed in places of worship such as synagogues, cathedrals, or mosques. The most famous and impressive examples can be found in Western Gothic churches such as the famous Sainte-Chapelle with its remarkable stained-glass windows illustrating the Passions of Christ.

The technique of using colored glass to create panels was developed in the Middle Ages. The technology was conceptually simple but difficult to master. After coming up with an original design, an artist asked the glassmaker to cut or crack pieces of colored glass that would later be assembled into a mosaic-like image using an iron base and melted lead to fix it. The principal issue was the distribution of the weight of metal and glass, which allowed the structure to remain vertically stable without cracking.

Sunlight coming through stained-glass windows created a mystical impression of the Holy Spirit’s presence, filling the churchgoers with religious awe. In the 20th century, the tradition of stained-glass windows was revived by avant-garde artists who introduced elements of abstraction or Expressionism into the pieces. Henri Matisse, Theo van Doesburg, and Marc Chagall are among artists who worked with stained glass, combining Medieval tradition with modernity. Today, the tradition of stained glass for churches remains alive: recently, Notre-Dame Cathedral commissioned a contemporary glass artist, Claire Tabouret, to create new designs to be installed after extensive restoration of the building.

Thomas Gainsborough’s Glass Paintings

Thomas Gainsborough was a revolutionary artist of the British 18th century who was born too early to be fully appreciated by his contemporaries. Gainsborough was mostly known for his society portraits of the British elites, which had a surprisingly fluid and airy style similar to that of the Impressionists a century later. However, he also extensively experimented with materials and techniques and created glass paintings that he then integrated into dark showboxes with candles inside. Burning candles lit up the glass panel from the inside, creating a magical, soft glow.

Gainsborough’s technique of glass painting was complex and completely determined by his material. His glass panels were supposed to be viewed from the back, and thus, he had to completely reverse the painting process, applying shades and highlights first and slowly moving back to larger color fields and backgrounds. The glass panels Gainsborough used were much more fragile than today and thus require special conditions for their preservation.

Art Meets Science: Blaschka’s Glass Models

One of the most remarkable cases of glass used in artistic production was triggered not by the need for artistic expression but by a scientific need. In the 19th century, scientists who wanted to study marine biology had to travel to the sea and ocean coasts and settle nearby. Preservation of fish and marine vertebrates was impossible, as marvelous molluscs, medusas, and actinias turned into piles of smelly mucus minutes after they were removed from their natural habitat.

The person who found the solution was Dresden-born glassmaker Leopold Blaschka. During his trip to the US, Blaschka sketched dozens of images of various marine fauna and later turned them into glass models. Outstandingly precise and lifelike, these models were purchased by Harvard University to train their marine biologists. Museum curators complain that the technology Blaschka used is almost impossible to replicate today, which makes the pieces’ restoration an incredibly challenging task.

Art Nouveau & Art Deco Glass

Art Nouveau as an aesthetic movement relied heavily on applied arts and affordable materials, at the same time producing pieces of astonishing complexity. Their main inspiration came from natural forms and images of plants, insects, and animals. Glass was one of the most popular materials for Art Nouveau designers, used for vases, windows, and accessories. One of the most influential glass designers of the Art Nouveau era was Louis Comfort Tiffany, the man behind the famous Tiffany lamps. Tiffany took traditional techniques and launched complex experiments with oxides and acids in order to create unique tones and textures.

Frequently confused with Art Nouveau due to a similar name and adjacent epochs, Art Deco nonetheless had a radically different aesthetic. Instead of fluid organic forms of Art Nouveau, Art Deco designs relied on geometry and angles, celebrating the high-tech aesthetic of the 1930s. It relied heavily on synthetic materials but also actively used glass for design. Art Deco glass is thick, framed with bold cuts into expressive geometric forms. A popular trend of the time was Uranium glass, produced with the addition of oxide diuranate into the mixture. The slightly radioactive substance made glass vases and sculptures glow under UV light.

Timo Sarpaneva

Timo Sarpaneva was a Finnish artist and one of the pioneers in introducing glassworks to contemporary design. Sarpaneva blended the aesthetic and practical functions of objects, forging the now-signature minimalism of Finnish design. He developed a new method of creating spherical spaces inside glass bodies: instead of blowing through a tube, he inserted a wet stick into a hot glass mass, causing evaporating liquid to widen the space. From the mid-1960s, Sarpaneva moved from making practical glass vessels like vases to glass sculptures. According to police data, Sarpaneva is one of the most frequently forged Finnish artists.

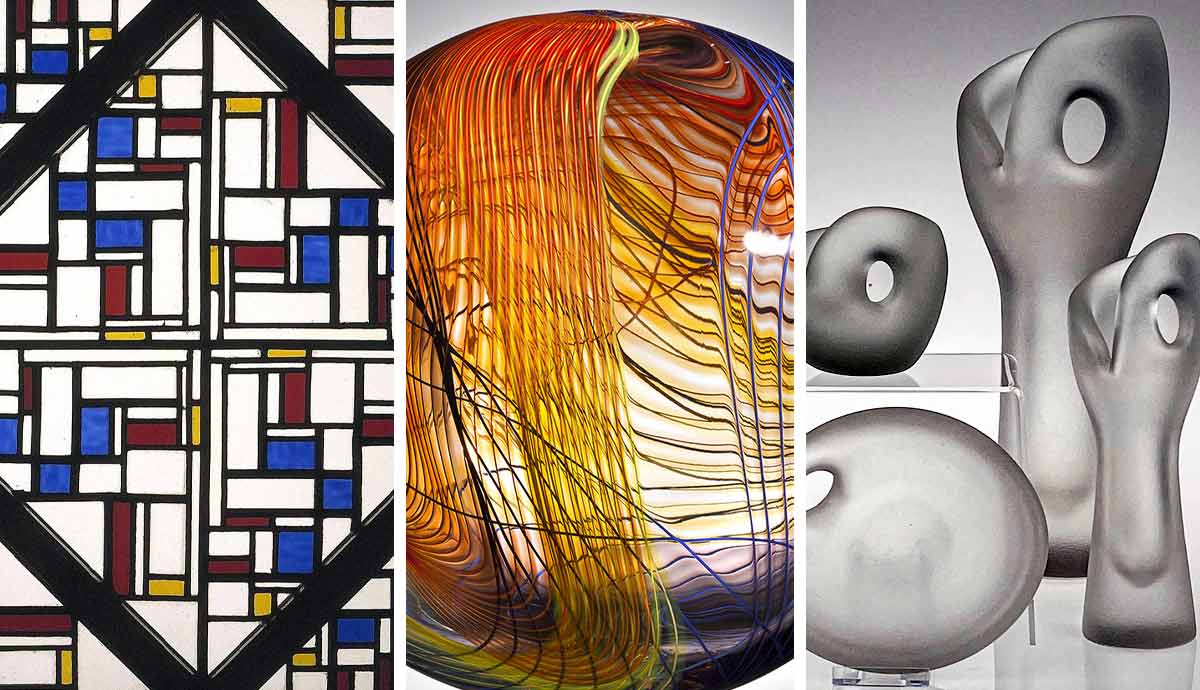

Lino Tagliapietra

Lino Tagliapietra is one of the legendary figures in contemporary glassmaking. Born in Murano, he became an apprentice to a famous local glass master before his teens. From the centuries-long Venetian tradition, Tagliapietra developed an expressive language of form and pattern, valued worldwide. He became a well-known master when he was only 25. Tagliapietra helped give new life to the wavering tradition not only in his native Italy but also in the US. Apart from creating unique and intricate glass forms, Tagliapietra is famous for his masterful manipulation of air. He skillfully incorporates air bubbles of various sizes and forms into his pieces in a way that they create additional patterns.

Dale Chihuly, the Contemporary Glass Art Master

One of the most famous and influential artists of contemporary glass making is not an Italian, but an American, Dale Chihuly. As a young man, Chihuly studied interior design but abandoned his studies to focus on glassmaking. He traveled to Italy and the Czech Republic to study local glass traditions and learn from masters. Unfortunately, after a 1979 shoulder trauma, Chihuly lost the ability to make glass himself, so he employs trained assistants who apply his technologies. Chihuly’s glass works are not objects to put on display but complex installations that create environments within themselves. Complex and dynamic, they create an impression of living organic matter.