Born in Arezzo, Italy, in 1304, Francesco Petrarch devoted his life to the study of Classical authors and literature. A frequent traveler throughout Europe due to his diplomatic activities, Petrarch came into contact with several men of learning and became a leading scholar and poet. In 1341, he was crowned as poet laureate in Rome. Petrarch’s Il Canzoniere, a collection of poems focusing on his love for Laura, had a lasting impact on European literature, influencing Renaissance lyric poetry with its form and language.

Quick Facts About Petrarch

| Fact | Detail |

| Full name | Francesco Petrarca (anglicized as Petrarch) |

| Born | 1304 – Arezzo, Tuscany, Italy |

| Family | Father – Ser Petracco (Pietro); mother – Eletta Canigiani; one younger brother – Gherardo |

| Education | Studied law at Carpentras, Montpellier, and the University of Bologna before turning to Classical literature |

| Early patron | Cardinal Giovanni Colonna in Avignon (from 1326) |

| Church career | Took minor ecclesiastical vows in 1333 for financial independence |

| Major works | Il Canzoniere (366 poems), Secretum meum, De viris illustribus |

| Scholarly achievements | Rediscovered lost works of Cicero (incl. letters to Atticus, Brutus, Quintus) and assembled the era’s finest private library |

| Peak honor | Crowned Poet Laureate of Rome in 1341—the first since antiquity |

| Legacy | Key figure of early Humanism; bridged Middle Ages and Renaissance; inspired “Petrarchism” across Europe |

| Died | July 1374 at Arquà (today Arquà Petrarca), Veneto, Italy |

Francesco Petrarch’s Early Years

Petrarch was born Francesco Petrarca in 1304 in Arezzo, Tuscany. Three years later, when the family was living in Incisa in Val d’Arno, Petrarch’s parents had another son, Gherardo. His father, Ser Petracco (a nickname for Pietro), had to leave his hometown of Florence in 1302 after the White Guelfs, the political faction he supported, were ousted by the opposing Black Guelfs. In the same year, poet Dante Alighieri, also a supporter of the White Guelfs, was similarly exiled from Florence, never to return.

In 1312, Ser Petracco left Italy for Avignon, taking his wife and two children with him. In Avignon, the southern French city where the papacy had relocated in 1309, Petrarch’s father secured a place as a notary at the papal court and encouraged his sons to follow in his footsteps. Thus, Francesco was sent to Carpentras and then Montpellier to study law. In 1320, Petrarch and his brother Gherardo returned to Italy to continue their studies at the renowned University of Bologna.

While young Francesco enjoyed his time in Bologna (“I do not think that one could find a more beautiful or more free place in all the world”), he was not passionate about his studies, preferring Classical texts and literature to law books. During this period, he also began collecting books and manuscripts, a habit that would ultimately lead him to own the most extensive and remarkable private library of his time.

In 1326, after his father’s death, Francesco Petrarch abandoned his law studies to focus on literature and the humanities. In need of financial stability, he left Bologna for Avignon, where he managed to secure the patronage of the wealthy and influential Cardinal Giovanni Colonna. In 1333, Petrarch took minor ecclesiastical vows, a decision that would allow him to gain a greater financial independence and pursue a career in the Catholic Church.

Taking the orders did not prevent Petrarch from enjoying the earthly pleasures offered by the polished papal court of Avignon. For the rest of his life, the poet would be torn between his religious faith and his desire for prestige.

A Love for Classical Culture: Petrarch & Humanism

In the 1330s, Francesco Petrarch traveled extensively throughout Europe, visiting France, Flanders, Brabant, and the Rhineland. Unlike Dante, who was deeply involved with the political life of his hometown and spent his life yearning to return to the “bell’ovile” (beloved fold), Petrarch described himself as rootless: “I am a citizen of no place, everywhere I am a stranger.”

While the lack of a stable homeland left the poet feeling restless (Jacob Burckhardt called him “the first truly modern man”), the constant wandering allowed Petrarch to come in contact with the most influential men of learning of his time and search for “lost” classical manuscripts in libraries. In Liège, for example, he recovered copies of two speeches penned by Cicero. In 1345, while residing in Verona, he discovered Cicero’s letters to Atticus, Brutus, and Quintus.

Throughout his life, Petrarch repeatedly drew on Classical authors and works as a source of literary and, most importantly, moral inspiration. While Dante also turned to Classical culture as a basis for his Commedia (the Latin scholar Virgil served as a guide during his journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise), the Florentine poet, like his fellow medieval scholars, did not view the Classical world as a historical period distinct from his own. Thus, he assimilated tropes and figures of Classical culture directly into his Christian worldview, presenting them as allegories or metaphors of the Christian message.

Petrarch’s attitude to the Classics significantly differed from that of Dante. A deeply humanist scholar, Petrarch promoted the continuity between antiquity and 14th-century society. However, he approached the Classical texts as a philologue, recovering, editing, transcribing, annotating, and stripping them of their religious allegorical readings. In this sense, Petrarch’s study of the Classical authors laid the foundations for the Renaissance movement. Rejecting the sterile arguments of medieval Scholasticism, he promoted the values of Classical culture in an attempt to reconcile the pagan world with Christian doctrine.

The idea of continuity between the two worlds is evident in his De viris illustribus (On Illustrious Men), a collection of biographies (written in Latin) of heroes of Greek and Roman history as well as Biblical figures.

A Modern Man: Crisis & Self-Discovery

While Petrarch managed to reconcile his admiration for the pagan Classical culture with Christianity, the poet experienced a profound moral crisis born from his pursuit of earthly pleasures and the inability to lead his life according to his religious faith, rejecting worldly affairs to find peace in God. Likely precipitated by his brother’s decision to enter monastic life, Petrarch’s inner conflict underlies his theological and literary works.

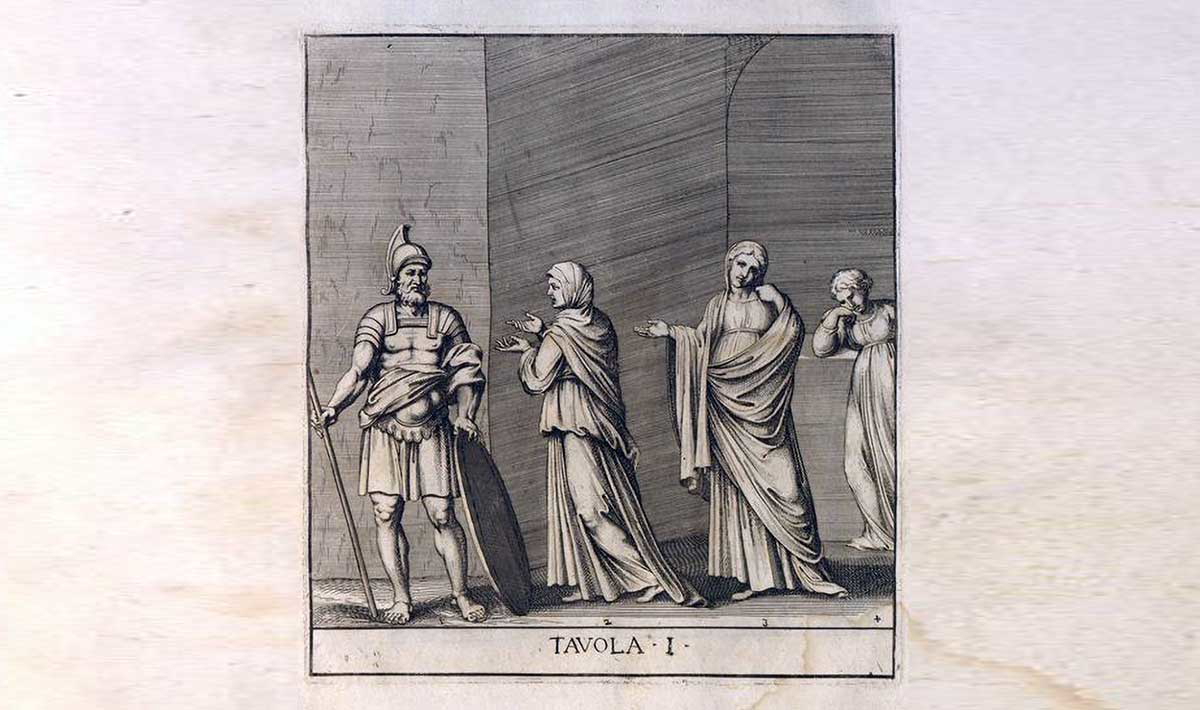

At the height of his crisis, around 1342 and 1343, shortly after being crowned poet laureate in Rome, Petrarch addressed his inner duality in Secretum meum, a treatise consisting of three imaginary dialogues between the poet and St. Augustine in the presence of a beautiful woman, an allegory of the Truth.

Despite the Father of the Church’s guidance, however, Petrarch’s anguish and feelings remain unresolved. The inner peace the poet yearns for, ultimately, remains beyond his reach. In his self-awareness and crisis, Petrarch is no longer a medieval man. He foreshadows the Renaissance movement and, even, modernity.

Critics have seen traces of Petrarch’s shift away from the medieval way of thinking in a letter written by the poet to his friend, supposedly in 1336. In the missive, Petrarch described his and Gherardo’s ascent to Mount Ventoux. In particular, the act of climbing to the top of the mountain to admire the surrounding vast landscape and admire the beauty of nature is often cited as a mark of Petrarch’s Humanism and a prefiguration of the Renaissance.

In the letter, however, the ascent to the mountain is less a premonition of things to come and more an allegory of Petrarch’s inner crisis. While his brother takes a path leading straight to the peak, the poet’s chosen path is more tortuous, causing him to descend to valleys and to lose his way several times—a clear allegory to Petrarch’s inability to resist temptation.

The conflict between the two opposing forces coexisting in his psyche is directly referenced in the letter: “These two adversaries have joined in close combat for the supremacy, and for a long time now a harassing and doubtful war has been waged in the field of my thoughts.”

Francesco Petrarch’s Il Canzoniere

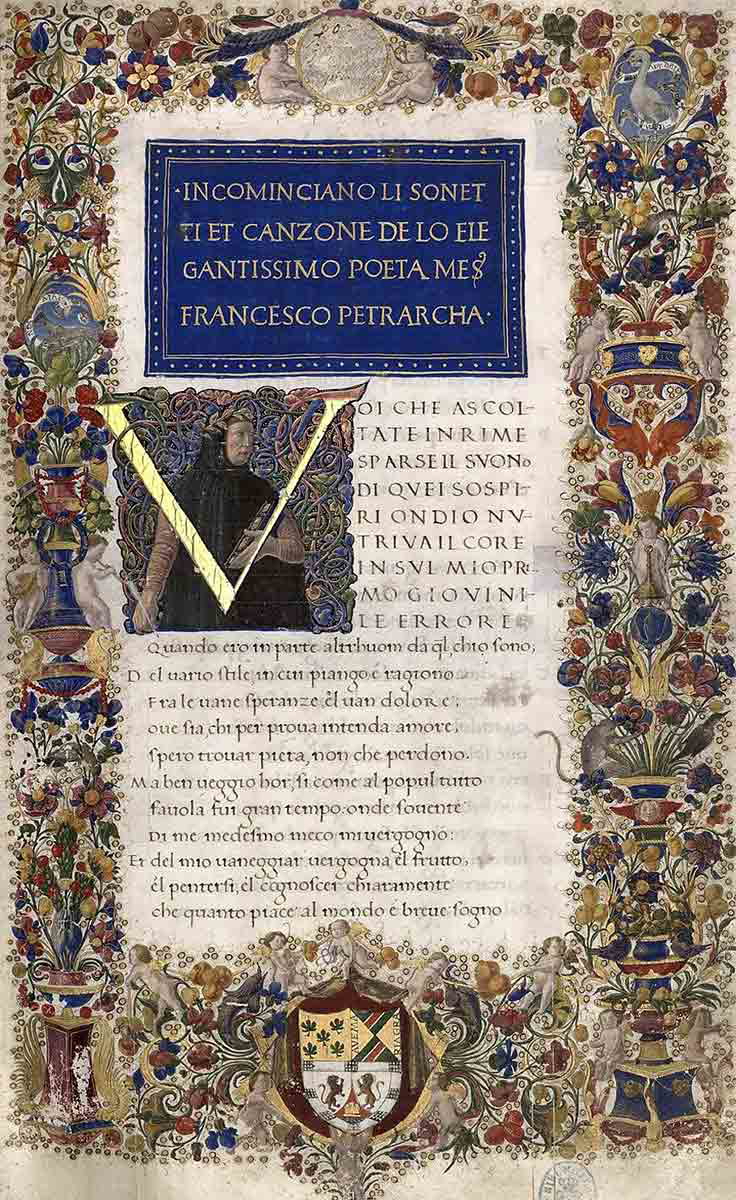

Petrarch’s inner conflict is also at the center of his most famous poetic work, Il Canzoniere. Also known as Rerum volgarium fragmenta (Fragments of Vernacular Matters) and Rime (from the first verse of its first poem), Il Canzoniere is a collection of 366 poems (songs, sestine, ballads, and madrigals), including 317 sonnets. Petrarch wrote the poems over a period of about forty years until his death in 1347, often revising and editing his verses.

The central theme in Il Canzoniere is Petrarch’s courtly love for Laura, a married woman he allegedly saw for the first time on April 26, 1327, in the church of St. Clair of Avignon, and loved from afar until her death in 1348 during the plague pandemic known as the Black Death. Little is known about Laura, as Petrarch offered only sparse information about her in his works. As a result, efforts to identify her have been unsuccessful. At the same time, the suggestion that she was a figment of Petrarch’s imagination has been discarded by most scholars.

In the final draft of Il Canzoniere, Petrarch arranged the poems chronologically and divided them into two parts: Rime in vita di Laura (Poems During Laura’s Life) and Rime in morte di Laura (Poems After Laura’s Death). Besides illustrating the evolution of his love for Laura, the chronological arrangement of the collection had the clear goal of serving as an allegory for the poet’s own inner journey, from the errors of his youth to the later asceticism, from the pursuit of worldly glory to the search for God.

Like in other works, however, Il Canzoniere does not offer a definitive solution to Petrarch’s split psyche. The poet, however, did not translate his sense of restlessness into his lyrics. Indeed, his poems are limpid and precise in both structure and language. The harmonious form and lyrics were the result of Petrarch’s careful avoidance of terms that may be too emotionally charged or sound harsh.

Francesco Petrarch’s Later Years & Legacy

Concentrated on his inner conflicts, Petrarch was not directly involved in the political landscape of the 14th-century Italian peninsula. In 1347, he lent his support to Cola di Rienzo’s unsuccessful attempt to restore Rome as the capital of Italy and reestablish a Roman Republic. His backing for Di Rienzo cost him the loss of the patronage of Cardinal Colonna, whose influential family firmly opposed Cola’s ambitious project.

Around the same years, tired of the constant maneuvering of the Avignon court, Petrarch moved to Padua, where his new patron, Jacopo II da Carrara, made him canon of the city’s cathedral. In the following years, he went to Milan, Parma, Verona, and Venice. Though he took part in various diplomatic missions, Petrarch longed for the quiet he found in his house in Arquà (now Arquà Petrarca), a small town on the Euganean Hills near Padua. It was in his Arquà residence that Francesco Petrarch died in July 1374. According to legend, he was found with his head reclining over a manuscript of Virgil.

For centuries after his death, Petrarch had a profound impact on European literature, not only in Italy but also in Spain, France, and England, where his legacy gave rise to a literary phenomenon known as Petrarchism. His poems and lyrical style influenced generations of poets and scholars, who accepted his Canzoniere as the standard by which other works would be judged.

Petrarch’s influence and legacy, however, were not merely a matter of form, but rather of a new way of thinking. Standing between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, he embodied the humanist spirit, foreshadowing a new era and a new attitude toward the past, religion, and the human experience.