Gangrene was a terrifying disease that caused many deaths during the American Civil War. The miserable, cramped, and dirty conditions on the front lines made a perfect breeding ground for the disease. If gangrene wasn’t effectively cured with one of the various painful and often harmful treatments battlefield surgeons used, it commonly resulted in amputation, which in itself could be incredibly painful and traumatic.

What is Gangrene?

According to the NHS, “gangrene is a serious condition which occurs when an excessive loss of blood causes body tissue to die.” It attacks the toes, feet, fingers, and hands most commonly, but it can also affect other body parts.

Gangrene is caused by serious infection or injury, and the symptoms include but are not limited to discolored skin, swelling of the infected area, numbness or severe pain, and sores and blisters.

Today, gangrene is treated with antibiotics and/or surgery. The former fights off the infection, and the latter is either to remove the dead tissue or, in more extreme cases, to remove an entire limb.

What were American Civil War Hospitals Like?

The highly unsanitary living conditions on the front lines meant that disease was rife for the soldiers of the American Civil War. The hospitals were much the same and incredibly overcrowded, meaning diseases spread like wildfire. Two-thirds of the 750,000 soldiers who died in the Civil War died from diseases.

Many British surgeons who had experience from the Crimean War, where conditions were very similar, provided the Americans with advice on how to prevent the spread of gangrene. In their hospitals, the British had allowed each individual their own 1600 cubic feet (45.3 meters) of space, and this had stopped gangrene from spreading. However, the situation in America was so dire that in some Union hospitals, patients had as little as 175 cubic feet (4.9 cubic meters) each. This created the perfect conditions for spreading gangrene (and other diseases) between patients.

Another factor that contributed to the spread of disease in American Civil War hospitals was the general lack of medical and surgical knowledge at the time. Of course, surgeons and doctors in the past cannot be blamed for what they did not know; however, they did unknowingly create the perfect conditions for diseases to thrive.

This was because many did not understand how or why diseases spread and did not understand how to prevent them from doing so. Therefore, in many cases, what began as a minor battlefield injury quickly progressed into a devastating infection which often resulted in death.

Despite this, Civil War surgeons did take some steps in the right direction, even if they were somewhat misguided. For example, some noted the importance of ventilation and cut holes in the ceilings and walls of hospitals. But what these surgeons did not realize was that they were not just allowing fresh air into their wards but all the bacteria from the outside world and other parts of the hospital as well. Naturally, this only encouraged more infections among patients with compromised immune systems.

How was Gangrene Treated During the American Civil War?

To treat gangrene, doctors used a variety of substances, including:

“poultices of mud, flaxseed, slippery elm or charcoal…chlorinated soda water, extremely strong sodium hypochlorite solutions, nitric acid, tinctures of iodine and iron and turpentine…”

(Anna Comeaux).

These substances were often used mixed together and were both painful and ineffective. Some were so ineffective that they attacked not only gangrenous tissue but also attacked normal, healthy tissue, thus creating more problems.

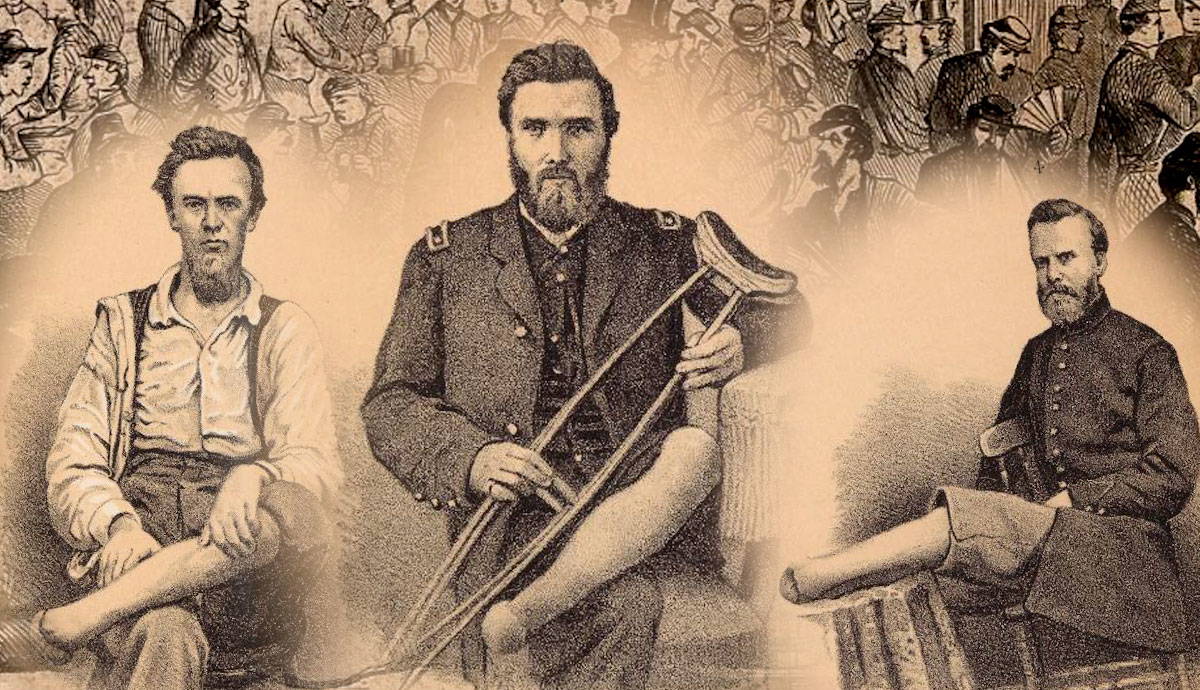

Another, more drastic way of treating gangrene was to amputate the affected limb. This was by far the most common method of treatment, and as a consequence, many surgeons became highly skilled at performing the surgery.

However, besides being extremely painful, these amputations could also increase the chance of infection. Not only did they leave an open wound exposed to bacteria in an already filthy environment, but the general lack of clean water at many sites meant that equipment could not be washed, nor could wounds or surgeons’ hands.

The incredibly unsanitary conditions in hospitals increased the chance of infection both before and after amputation. While surgical methods were primitive, surgeons did attempt to sedate their patients, often using chloroform or alcohol. However, these methods were only partially effective, and many patients were not completely unconscious during the surgery.

For example, Confederate general Stonewall Jackson noted that he could hear the cutting of the saw as it severed his arm from his body but did not feel the pain. Despite the pain and the danger, however, 75% of soldiers survived these amputations, and not all treatment was as horrific or primitive.

Some surgeons (when they could access water) recognized the importance of keeping their equipment, themselves, and their patients clean. Some even recommended healthy, balanced diets to their patients as a way to recover and ensured the affected area was kept clean and clear of any debris.

Furthermore, by the end of the war, surgery as a profession had come a long way, for it had provided many surgeons with a large amount of experience they would otherwise not have had.

Did Any Historical Treatments Actually Work? Goldsmith & Bromine

Middleton Goldsmith, a surgeon who served in the Union Army and worked in Louisville, Kentucky, made significant steps to effectively treat people with gangrene. Despite beginning as a Brigade Surgeon, Goldsmith climbed the ranks and became Surgeon-in-Chief of all the military hospitals in Kentucky.

Noting gangrene’s devastating effect on soldiers, he investigated the treatments used in the hospitals under his jurisdiction and documented his findings. Goldsmith concluded that while acids (like the nitric acid mentioned above) could be effective in treating gangrene, they were impossible to use because of the way they attacked healthy tissue.

However, he did notice patients who had been treated with bromine had higher recovery rates. Even though it could be highly volatile, Goldsmith recommended using bromine in all his hospitals. Acknowledging the issues with the aerosolized deodorant form of bromine (which was being used at the time of his study), Goldsmith developed a way to apply the substance, which was more predictable and involved injecting the substance directly into the patient’s muscles. He also recommended applying bromine directly to any exposed areas too; both methods were extremely painful.

Goldsmith recorded his findings in a report entitled A Report on Hospital Gangrene, Erysipelas and Pyaemia, as observed in the departments of the Ohio and the Cumberland, with cases appended (1863). The report included accounts of his cases as well as the data he had collected, which he presented in tables, and the records of conversations he had had with other surgeons on the subject.

The method gained attention, and eventually, a surgeon named G.R. Weeks conducted a study of Goldsmith’s methods. Weeks concluded only three of the 104 patients treated in the above manner died.

Weeks also noted that the three patients who had passed away had succumbed to pyemia and cellulitis, not gangrene. In fact, before their deaths, their gangrene had improved. Weeks was so impressed by what he saw that he concluded that bromine could be 100% effective in preventing death caused by gangrene.

Those who received pure bromine in this way recovered in two days, and those who did not recovered in about 15 days. Of the 304 patients to receive bromine treatment under Goldsmith’s jurisdiction, only eight died.

The method was eventually used across many of the field hospitals in America, but despite being effective in treating gangrene, it remained dangerous. Depending on the dosage and the nature of the exposure, bromine can irritate the skin, cause coughing, dizziness, watery eyes, and skin burns, and ingesting it can cause nausea and vomiting. Inhaling bromine gas for an extended period of time could cause long-term lung problems.

In addition to the dangers of poisoning, it was also excruciating both when applied topically and injected, and although bromine prevented the spread of gangrene, it could also harm healthy cells too.

To conclude, gangrene caused many soldiers a lot of pain and fear during the Civil War. Despite efforts to improve conditions and develop effective treatments, the disease still claimed many lives and caused a lot of suffering.

Gangrene still exists today; however, with a modern understanding of how infections spread and how to treat them, not to mention antibiotics, it is much easier to treat and ultimately cure.