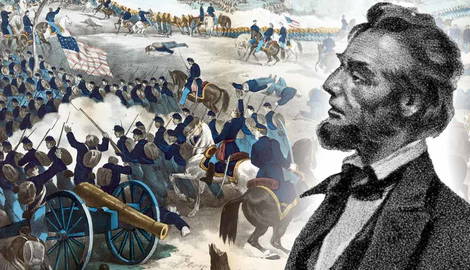

The Gettysburg Address stands out as one of the most iconic speeches, if not moments, in US history. At a critical point in the country’s history, Abraham Lincoln managed to summarize the principles on which the United States was founded in a dedication that has echoed through the ages. Surprisingly, though, Lincoln’s speech did not find much traction at the time, and it was only in the subsequent century that it began to gain prominence. Nevertheless, the events surrounding the Gettysburg Address deserve further exploration.

The Background: When Was the Gettysburg Address?

The Gettysburg Address was delivered in 1863, a few months after the titanic Battle of Gettysburg. Commonly regarded as the most pivotal battle in the American Civil War, it saw Union forces halt Confederate advances northwards. The Union victory in the fight began to turn the tide of the war, ultimately leading to the surrender of the Confederacy at Appomattox. One of the bloodiest days in US history, Gettysburg saw over 50,000 casualties.

Months after the battle, a ceremony was planned to consecrate the new National Cemetery at Gettysburg. The site of the cemetery was purchased by the government of Pennsylvania on the location of the original battlefield. Planned for November 19, 1863, the event was expected to draw a crowd of around 15,000, a slew of reporters, and six state governors.

Only invited a few weeks beforehand, Abraham Lincoln was in a poor state of health in the days leading up to the address he would give. Suffering from what would eventually be diagnosed as smallpox, the president felt dizzy throughout the day. He was unable to talk to a crowd that had gathered outside his room the night before, and his aides were unsure if he would be able to deliver the speech.

The day was planned as mostly a mix of music by various bands and choirs, as well as prayers led by religious leaders. Lincoln’s speech was not the major event of the day, however. That was an oration led by Edward Everett. Everett was a former senator and secretary of state from Massachusetts who had worked diligently to keep the Union together during its time of crisis. Regarded as one of the best speakers in the country, Everett planned to recount the battle and lay out the future of the United States.

In a two-hour address (which was typical for the time), Everett totaled 13,000 words without any notes to draw from. His address mentioned a variety of conflicts throughout history, primarily from the English Civil War, as well as from other civil wars in Europe. The Battle of Gettysburg was also described in vivid, meticulous detail. After Everett had finished, there was a short hymn before it was time for Abraham Lincoln to take to the podium.

The Gettysburg Address: Facts & Debates

Like Everett’s speech, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address also drew from historical sources and biblical references. This time, he went even further back. Scholars have compared Lincoln’s speech to Pericles’ Oration (recorded by Thucydides) during the Peloponnesian War.

Indeed, the Gettysburg Address follows a similar path to Pericles. It acknowledges the events leading up to the speech, emphasizes the democracy being fought for, reaffirms the need to honor the sacrifice of those who died in battle, and then commits to continuing the fight. “This nation,” declared the US president, “under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.”

Then, Lincoln concluded the speech with potentially the most famous quote in any American speech, asserting that “a government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

There is a dispute amongst historians as to what Lincoln said exactly. Five copies of the speech were given out, each slightly differing from the others. Two were given to Lincoln’s secretaries around the day of the speech, and three were sent afterwards to those who requested them.

The biggest debate centers on whether Lincoln used the words “Under God,” indicating a direct religious influence behind his speech, or, conversely, he sought to maintain the separation between church and state. The two early copies of the speech do not include them, yet they do appear in the later versions. Reporters at the event confirmed that he did, in fact, pronounce those words, yet the debate still remains.

What has emerged as the most popular version of the address is the Bliss copy (each version is named after the person who received it). Alexander Bliss was a colonel in the Union Army who wanted to add the speech to a collection aimed at raising money for veterans. The Bliss copy is the only one that Lincoln himself signed. We will not know for certain exactly what Lincoln said at Gettysburg, but the following is a rough consensus amongst modern-day historians (taken from the Library of Congress):

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The Fallout From the Gettysburg Address

In the context of the American Civil War, the Gettysburg Address had little impact. The Union was already in the ascendancy and continued to press into the South. A few Confederate victories would slow their advance, but the overwhelming force of the Union was too much for the rebels.

As for the speech itself, it was not received that well. Reports from the event highlight muted applause and surprise at the brevity of the president’s remarks. Broader reception for the speech fell along partisan lines.

Those who loved Lincoln praised it, saying it was a testament to the United States. Those critical of the president said it embarrassed the United States and was not becoming of the time. Foreign media were also critical of the Gettysburg Address, arguing that the short speech did not live up to their expectations of the president as the totemic figure he was said to be.

The strongest praise for the speech came from Edward Everett, who requested a personal copy from Lincoln. Despite being the main speaker for the event, Everett highlighted how Lincoln’s short oration managed to summarize everything he had wanted to deliver. However, reflections on the consecration still focused on Everett.

It was only after the Union was victorious in the Civil War and Lincoln’s assassination that the speech started to gain international prominence. Lincoln’s dramatic murder enshrined him in American consciousness, so that by the turn of the century, the Gettysburg Address was one of the mainstays of US political culture.

Many tried to recreate the titanic overtones of the speech, particularly during the crisis periods of the First and Second World Wars. The speech would even gain fame abroad, with much of its language being incorporated in the Constitution of Japan in 1947.

The Legacy of the Address

More political turmoil in the 1960s would further catapult Lincoln’s address into the consciousness of the American public. Martin Luther King Jr. was clearly influenced in his speech at the Washington Monument, beginning with a similar reference to time, “five score years ago,” a clear indication that Lincoln’s address had now become a centerpiece of US political culture.

John F. Kennedy would also use similar language in his inaugural address and in subsequent speeches. This again highlights how the Gettysburg Address came to be a common theme for groundbreaking political movements.

Even today, there still exists confusion about the information surrounding the Gettysburg Address. Multiple attempts have been undertaken to recreate the site from where Lincoln gave the speech. Limited photographic evidence has made this difficult, and therefore, several different locations have been proposed.

Despite some murkiness surrounding the speech itself and its muted reception in the immediate aftermath, the Gettysburg Address stands today as one of the greatest presidential addresses. In the context of a raging civil war, it helped outline the democratic principles of the United States and justify the Union cause, all within two minutes.