The Arts and Crafts Movement was one of the most significant movements in interior design, architecture, and decorative arts that arose in Great Britain in the 19th century. Defined by its celebration of harmonious interior spaces and individual craftsmanship, it was born from a preexisting culture of fascination with medieval history and aesthetics. This fascination was manifested particularly strongly through the Gothic Revival, which had shaped British architecture throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Many key moments in the Arts and Crafts Movement intersected with the Gothic Revival.

Setting the Stage for the Arts and Crafts Movement

While a variety of revivalist movements in architecture arose in Great Britain in the 19th century, one of the most impactful was the Gothic Revival. The Gothic Revival had actually originated in the 18th century, with early structures such as Strawberry Hill House striving to recreate the beauty and drama of historic Gothic architecture. By the 19th century, Gothic Revival architecture had taken on patriotic connotations for Great Britain, with many feeling that it was a representation of British history and national identity.

This attitude was reflected in the prominence and cultural significance of the types of structures that came to be associated with 19th-century Gothic Revival architecture, such as the Houses of Parliament in London and the Scott Monument in Edinburgh. Not only was the Gothic Revival expressed through architecture, but it also made its presence known in interior design and decorative arts. Indeed, an entire room could be furnished and decorated in a Gothic Revival manner, resulting in a style that often felt truly all-encompassing.

Many of these concepts were formative for the Arts and Crafts Movement, which came into its own towards the end of the 19th century. A reverence for the Middle Ages in which Gothic architecture had arisen was at the heart of the Arts and Crafts Movement, with medieval aesthetics influencing much of its output. Similar to the architects and designers of the Gothic Revival, leaders in the Arts and Crafts Movement, such as William Morris, oversaw the creation of entire rooms that reflected the ideals of the movement. With so many foundational principles in common, it is hardly surprising that the two movements intersected in many unprecedented ways throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

An Intergenerational Transition: The Pugin Family

One of the most influential instances of intersection between the Gothic Revival and the Arts and Crafts Movement occurred in the Pugin family. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin was born in 1812 to a father who had fled France during the French Revolution. Pugin was fascinated by Gothic architecture from a young age, particularly the way it had manifested itself in the 14th century, and had already become a designer of silver and furniture by the age of fifteen.

Pugin eventually became one of the most prominent leaders of the Gothic Revival in Great Britain in the 19th century. He was even involved in the integration of Gothic design elements into the aforementioned Houses of Parliament. In his writings, Pugin put forth the idea that Gothic architecture had a religious dimension that set it apart from other architectural styles. At the same time, Pugin argued that every aspect of a design should have a function and purpose, which was extremely important for the later development of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

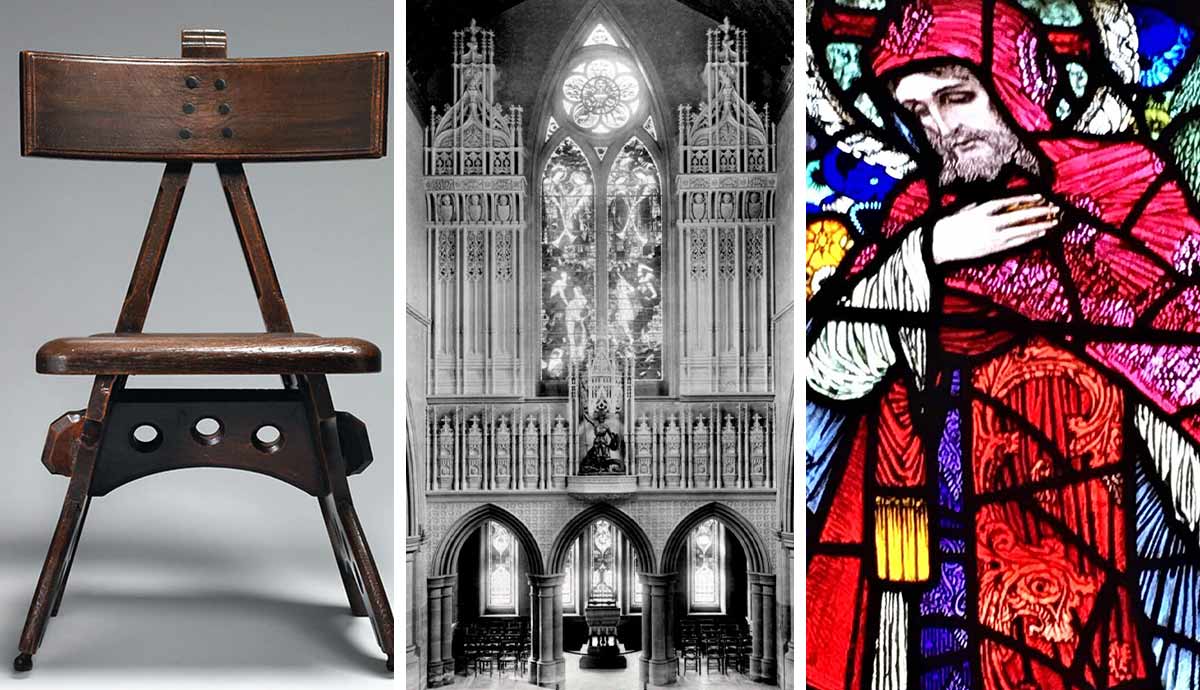

Pugin’s oldest son, Edward Welby Pugin, also became an architect of repute. Mainly associated with the Catholic churches he constructed throughout Britain and Ireland, Edward Welby Pugin’s most ambitious project was the Granville Hotel, which he designed at the end of his career. As Edward Welby Pugin envisioned it, the Granville Hotel’s architecture and interior design in many ways followed the Gothic Revival. Interestingly, one of the most widely reproduced elements of the hotel was a side chair design he created for it that came to be known as the Granville Chair.

Edward Welby Pugin created the chair in line with his father’s vision that the substance a piece of furniture was constructed from should not be masked as another substance. With its exposed nails and simple design, the chair comes across as a distinctly Arts and Crafts piece. The older Pugin’s advice, therefore, can be said to have led his son down the path of Arts and Crafts furniture production, cementing Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin’s status as a true progenitor of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Red House

The architecture and interior design of the Granville Hotel reveal that key Arts and Crafts features often emerged within structures where they coexisted with the Gothic Revival. The Granville Hotel, constructed in the late 1860s, was not the first structure in 19th-century Britain in which this coexistence could be found. One of the earliest of these was Red House, whose planning began in 1859.

Red House was constructed for William Morris as a family home at an early phase in his career. Its construction was led by Morris’ friend Philip Webb, who had previously studied under Gothic Revival architect George Edmund Street. Webb similarly added many Gothic features to Red House. The roof of the house, for instance, is steeply slanted, echoing 13th-century roofs. In this way, the house drew from a specific era of Gothic architecture in the manner of many Gothic Revival structures that had come before it. Also, the porch of the house is dominated by a Gothic arch, and even the main staircase bears spires evocative of those seen on Gothic cathedrals.

Interspersed amidst the Gothic details is an emphasis on materiality, felt through features such as exposed beams and wooden joints easily located throughout the structure. Morris and his inner circle personally worked on the decoration of the house, creating murals, cloth wall hangings, and other additions that made the home feel more inviting. The strong sense of the craftsman’s hand that these elements created went on to become one of the Arts and Crafts Movement’s defining traits. Indeed, Red House is generally perceived as a seminal work of Arts and Crafts architecture, laying the groundwork for future developments in the movement. The Gothic Revival architectural features of the house blend seamlessly into its Arts and Crafts aesthetic, demonstrating that in its earliest phases, the Arts and Crafts Movement often intersected and merged with the Gothic Revival that had come before it.

St. George’s Church

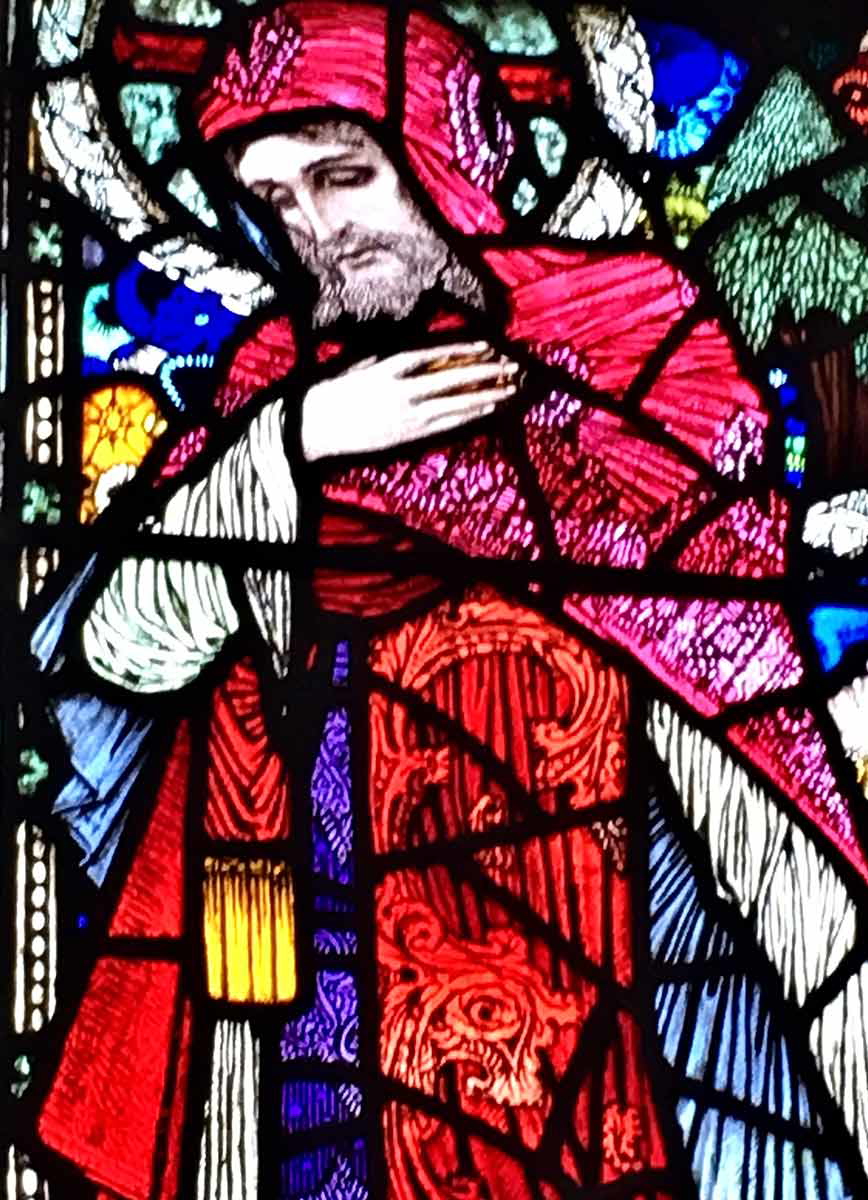

The Arts and Crafts Movement did not solely intersect with the Gothic Revival within secular structures, but within religious structures as well. One of the most striking examples of this phenomenon occurred when the Anglican St. George’s Church, Jesmond, in Newcastle, finished construction in 1891. Charles Mitchell, a Scotsman who had made his fortune in the shipbuilding industry, commissioned St. George’s. North Yorkshire architect and painter Thomas Ralph Spence was responsible for its architecture. Like Red House, St. George’s incorporates many elements in its architecture that are derived from specific Gothic prototypes, in the vein of the Gothic Revivalism that has been described thus far.

Charles Mitchell was a great admirer of French art and architecture, and Spence seems to have specifically referenced French prototypes for the church in order to suit his tastes. For example, the rounded columns holding up the arches in the church’s interior are reminiscent of those seen in French churches towards the end of the Middle Ages. Also, the church’s tower employs tracery in the French Flamboyant Gothic style. At the same time, the external decoration of the church was rendered in an early style of Gothic architecture known as First Pointed Gothic.

It is in the decoration of the church where its Arts and Crafts flair can be felt. Thomas Ralph Spence was a member of the Art Workers’ Guild, an organization that aligned itself with the ideals that Arts and Crafts leaders like William Morris celebrated. For this reason, the church excels in its handcrafted details, such as delicate mosaic patterns and ornate carvings. Furthermore, much of the work on the church as a whole was completed by other members of the Art Workers’ Guild, firmly ensconcing the church within the realm of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Given its unusual application of Arts and Crafts sensibilities into a religious setting, the church was considered extremely innovative for its time, with some of its details even appearing to formulate into their own variant of Art Nouveau. In its own creative way, St. George’s united the ideals of skilled craftsmanship and medieval authenticity that connected the Gothic Revival and the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Gothic Revival and the Arts and Crafts Movement in Ireland

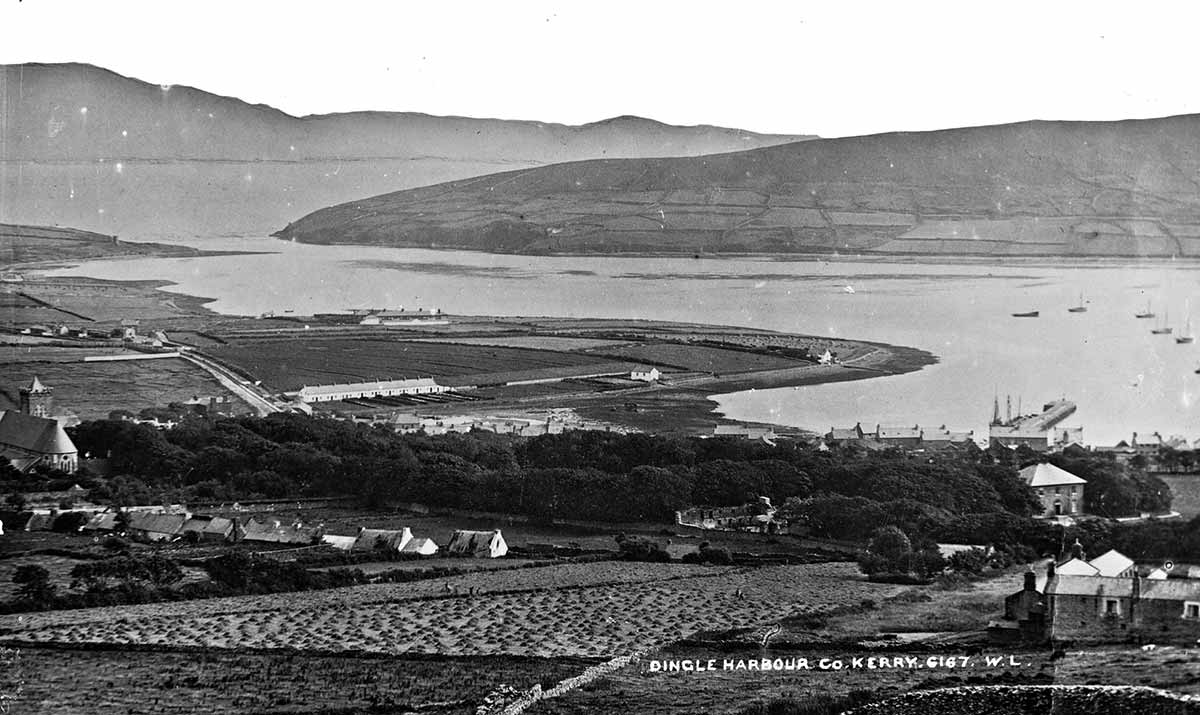

The Arts and Crafts Movement continued to intersect with the Gothic Revival in the 20th century. In the early 1920s, for instance, a series of stained glass windows by Arts and Crafts artist Harry Clarke was added to the Gothic Revival Chapel of the Sacred Heart in Dingle, Ireland. This Catholic chapel had originally been constructed in the 19th century by architect J.J. McCarthy. It was in 1922, when the chapel was being renovated, that Clarke was brought in to create the new windows by Mother Ita Macken. These windows depicted six different scenes from Jesus Christ’s story, namely The Visit of the Magi, The Baptism of Jesus, Let the little children come to me, The Sermon on the Mount, The Agony in the Garden, and Jesus appears to Mary Magdalene.

The decision to hire Harry Clarke as the artist for the commission was a significant one. A native of Dublin born in the late 1880s, Clarke was building a reputation as a prolific artist in the realm of both stained glass windows and illustration. Culturally, Clarke was an extremely important individual, as he was one of the most influential artists of the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement of the early 20th century. Similar to its English equivalent, the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement celebrated Ireland’s medieval heritage of art and design.

In the context of the Ireland of 1922, which was emerging from the Irish War of Independence, the movement was also deeply symbolic of Ireland’s future and national identity. Through Clarke’s Arts and Crafts interpretation of the life of Christ, therefore, the Chapel of the Sacred Heart symbolically embraced Ireland’s future. At the same time, it is important to note that the chapel maintained Gothic Revival architectural features throughout the renovation. By allowing this historic architecture to remain in place, Mother Macken ensured that the chapel’s ties to Ireland’s past were preserved.