The second of the Ten Commandments states “You shall not make for yourself a carved image or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.” How believers have interpreted this commandment in different traditions has had a significant influence on their attitudes toward art and its use in religious practice. On the one hand, certain art forms have been interpreted as graven images, becoming taboo, while on the other, art has been embraced and has featured prominently in places of worship, playing a central role in the religious experience.

Art in Early Christian Antiquity

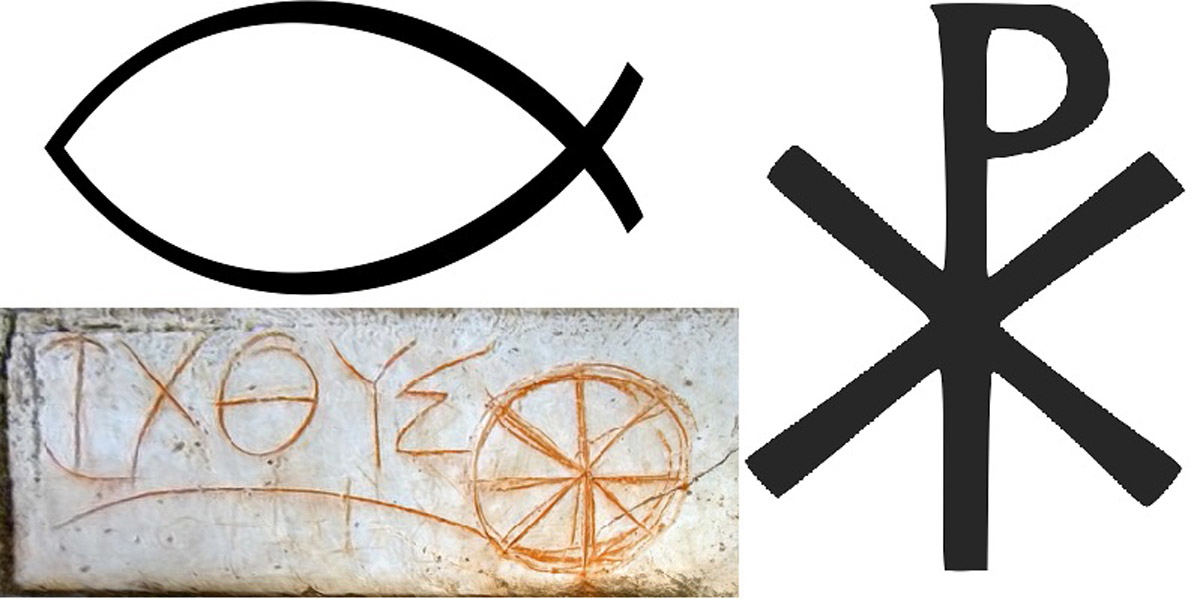

Early Christianity grew from a Jewish context in which the Ten Commandments were a non-negotiable set of laws to be interpreted and practiced literally. As such, Christians from the 1st to the 4th century tended to only make use of symbols that represented their faith. Two symbols from the early days of Christianity are widely recognized to this day. The first is the sign of the fish, which in Greek is the word ICHTHUS (ΙΧΘΥΣ), and served as an acronym for “Jesus Christ God’s Son Savior” (Ἰησοῦς Χριστός θεοῦ Υἱός Σωτήρ). It was a symbol that expressed the core beliefs they held dear. The second is the two Greek letters Chi (X) and Rho (P), superimposed on one another. These are the first two letters of the title “Christ.” In both instances, the uses were symbolic and pointed to Christ.

Christianity, as a new religion, would be distinct from paganism, which venerated statues of the gods and emperors. Their temples and places of meeting were elaborately decorated with depictions and sculptures of the deities they adored. Many pagan households would have small figurines of the gods they looked to for provision, protection, and healing. Originating in Judaism, Christianity continued the practice of not using statues or images in its religious practices.

Another likely contributor to the absence of Christian art during this early phase of Christianity was persecution. Because Christians mostly gathered in secret, the open and bold display of Christian art would put these faith communities at risk.

When Christianity was legalized in the 4th century under Constantine, a shift in the attitude towards Christian art occurred. Whether this was due to a pagan influx into Christianity, the emergence of Christian houses of worship, or both, is debatable. What is clear is that history shows evidence of an increase in depictions of Mary, Jesus, and the biblical narrative.

These depictions did not serve an aesthetic purpose alone. They also served as a tool to allow a largely illiterate populace to engage with and learn about their faith and the Biblical narrative. Christian art became commonplace in churches and the way in which scenes from the Bible were portrayed became more vivid. This trend lasted until the 7th century CE.

The Byzantine Iconoclasm (8th-9th centuries)

In the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire, tensions between the interpretation of the Second Commandment and how Christian art had permeated Christian places of worship reached a boiling point. Some clergy claimed that Christian art constituted “graven images” and led to idolatry. Others considered the art a “window to the divine” and a useful tool to educate and instruct the masses. The conflict led to the Iconoclast Controversy (726-843) which saw Emperor Leo III order the destruction of icons and other works of Christian art.

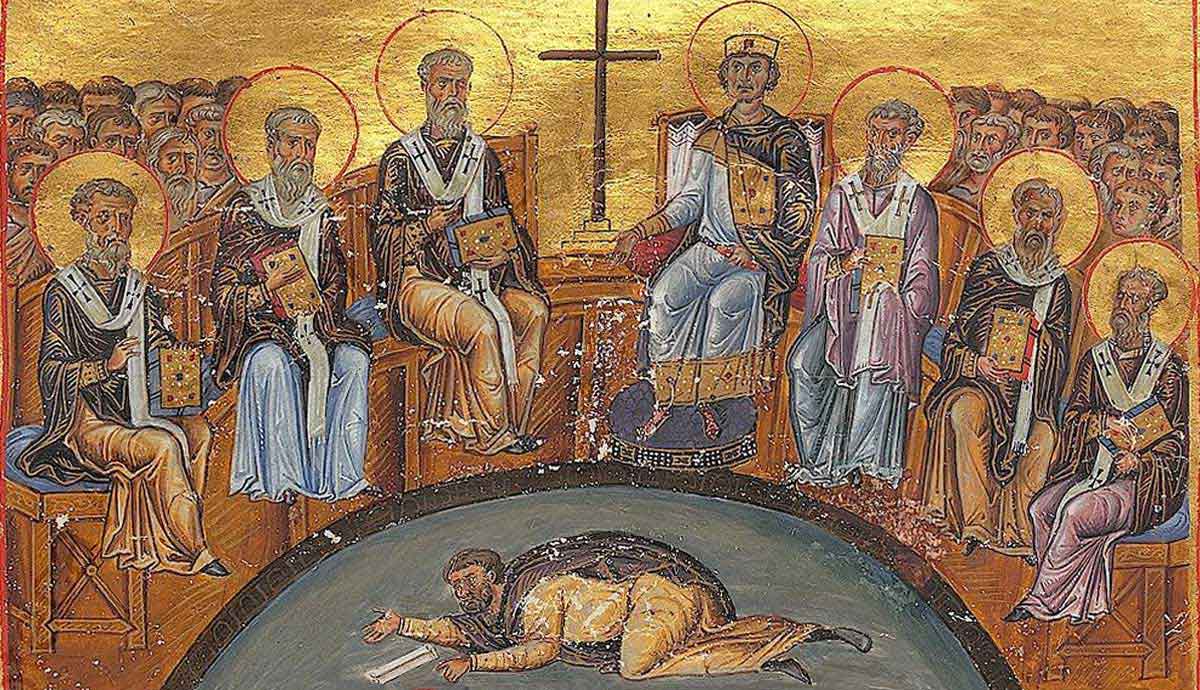

Some years later, the matter was discussed during the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 CE under Empress Irene, where several sessions in October considered the pros and cons, and a proper response to resolve the tension.

The result was that veneration of Christian art and depictions of the Biblical narrative was permitted, but only if it did not extend to the point of idol worship. The council declared:

“As the sacred and life-giving cross is everywhere set up as a symbol, so also should the images of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, the holy angels, as well as those of the saints and other pious and holy men be embodied in the manufacture of sacred vessels, tapestries, vestments, etc., and exhibited on the walls of churches, in the homes, and in all conspicuous places, by the roadside and everywhere, to be revered by all who might see them. For the more they are contemplated, the more they move to fervent memory of their prototypes. Therefore, it is proper to accord to them a fervent and reverent veneration, not, however, the veritable adoration which, according to our faith, belongs to the Divine Being alone—for the honor accorded to the image passes over to its prototype, and whoever venerate the image venerated in it the reality of what is there represented.”

This declaration seems to recognize the essence of the Second Commandment. Its intention was not to restrict or prohibit art but to forbid the worship of idols as Exodus 20:5-6 indicates. Yet, it recognized Christian art for its aesthetic and educational value.

The Golden Age of Christian Art

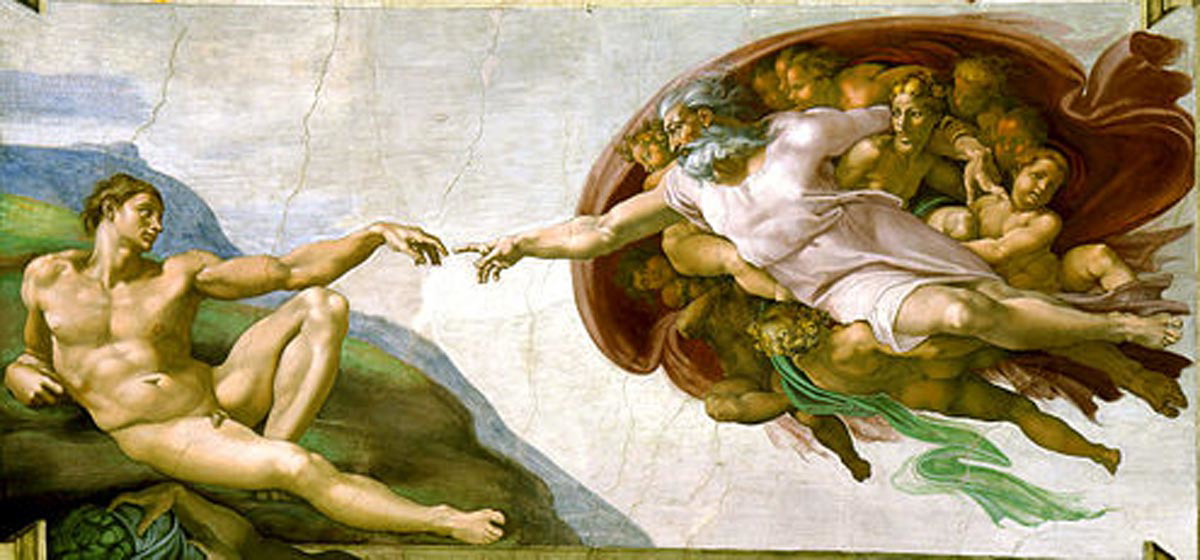

The Medieval Period is considered a golden age of Christian art by many. It is known for its increase in frescoes in cathedrals, sculptures, illuminated manuscripts, and stained-glass windows, all highlighting biblical narratives and bringing them to life in artistic and exciting new ways. In a sense, the honing of creative arts reflected the creative image of God in the artists.

At the end of this period in the Renaissance, Christian art reached its peak with works by Da Vinci and Michaelangelo. Arguably one of the best examples of Christian art from this era is the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican City. It depicts the most iconic narratives from the Bible. The Church embraced Christian art as a tool to reinforce teaching and emphasized its use as an aid rather than an object of worship.

Christian Art and the Reformation

The pendulum swung on Christian art again with the onset of the Protestant Reformation. The critique of the Catholic tradition reignited the debate on the use of images for worship in the light of the Second Commandment. Protestant regions saw a drastic rise in iconoclastic events where statues and works of art were removed from churches and destroyed. Protestantism desired a focus on scripture and preaching rather than on visual arts.

These differences in approach are clearly visible in the adornment of cathedrals and churches of the Catholic and Protestant traditions. Protestants opted for a more austere interior for their churches. Some Protestant traditions followed a moderate approach to the use of Christian art in their structures, allowing limited artistic expression.

Christian Art and the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation’s response to Protestant attitudes toward Christian art was dealt with largely at the Council of Trent (1545-1563). It reaffirmed the role of art in promoting devotion and teaching in the Catholic tradition and ushered in the Baroque Period. This timeframe is recognized for its exuberant use of imagery designed to inspire awe, instruct, and draw worshippers closer to God.

Baroque art is characterized by emotional expressiveness and dramatic use of light, drawing the observer into the religious experience. It stood as a stark witness to the different approaches the Catholic and Protestant traditions embraced until the latter part of the 19th Century.

Christian Art in the Modern and Contemporary Eras

The Enlightenment ushered in new approaches to art in general, which spilled over into the sphere of Christian art. With Protestantism splintering into many denominations, different groups adopted varying attitudes toward Christian art. Though the Catholic and Orthodox traditions remained true to their distinct artistic practices and use of sculptures and icons, many Protestant groups embraced more abstract works and, later, digital representations of art.

The expression of Christian art saw many cultural influences manifest themselves as people from different parts of the world created works from their native perspectives. It resulted in diverse reinterpretations of themes that have been the subject matter of artists throughout the Christian era. These reinterpretations have sought to bring the Biblical narrative to observers in ways that are culturally relevant, helping people to engage and understand the subject matter in ways that are significant to their context.

Lasting Tension and Dynamic Adaptation

From the time of the early Christian church to our day, attitudes toward Christian art have oscillated. Practices have ranged from iconoclasm to the opulent adornment of places of worship.

Today, groups like the Christadelphians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Amish, Old Order Mennonites, and some Puritan-inspired Christian denominations discourage the use of images in worship. They consider it a violation of the Second Commandment or at least a potential source of idol worship.

Some groups argue only against depicting the divine, whether it be God or the man Jesus, while others, like the Amish, avoid any depiction of created beings and the divine, including pictures or portraits of themselves and others.

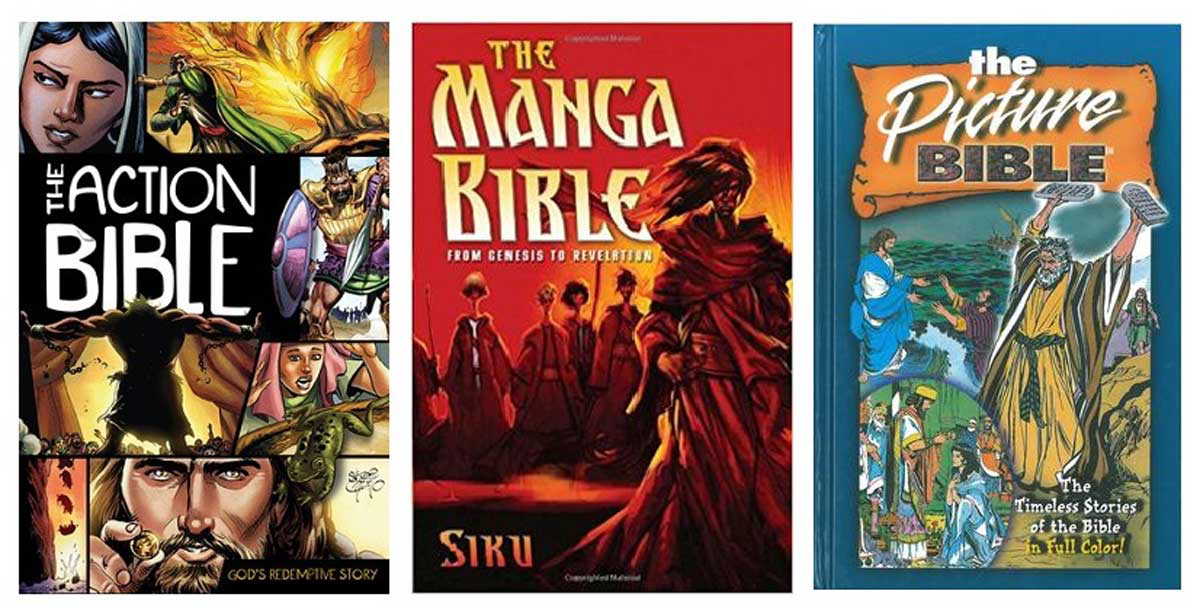

On the other side of the spectrum, comic book versions of the Bible have seen the light. The motivation for such a radically new presentation of the scriptures is to make the Bible accessible to younger audiences who may only be reached through innovative and creative artistic approaches that can compete with contemporary entertainment for youngsters. The result is visually stimulating Bibles, though they are textually poor versions of the original manuscripts.