The American nation under the US Constitution began with a compromise that, among other things, quelled the founding fathers’ anxieties over slavery and racial equality before the law. As the United States grew in size and influence, the very same issue would bring future leaders of America back to the compromising table—and even the end of slavery could not stop the nation’s further need for concessions.

1. The Great Compromise

When fifty-five white male landowning delegates converged on Philadelphia in 1787 to correct the federal government’s perceived weaknesses under the Articles of Confederation, it became evident that if they were to save their new nation, the men would need to form an entirely new national government that would stabilize the country’s faltering political, diplomatic, and economic situation after the American Revolutionary War. The proposed Constitution would grant more power to the federal government and strengthen a new nation from threats foreign and domestic. But first, the delegates and the people they represented from their respective states needed to get past the deep geographical and social divide that hindered national progress. Apart from the small states demanding changes that would protect their voting power against their larger counterparts, the Northern and Southern states could not agree on how the proposed US Constitution should treat slavery.

In what history would remember as the Great Compromise, the delegates settled on the ideas of Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut to balance the interests of states with large populations against those with smaller representation. Initially, the Virginia Plan proposed by James Madison favored the larger states when it called for a bicameral or two-chamber legislature with representation in both houses based on state population numbers, which granted more influence to those with more significant numbers of people residing within their borders.

William Paterson of New Jersey suggested a counter-proposal to Madison with a plan bearing his state’s name. This plan supported smaller states, calling for a unicameral or one-chamber legislature with equal representation for each state. Just as the impasse threatened to derail the entire convention and the creation of the new Constitution, Sherman and Ellsworth’s Connecticut compromise saved the day by blending elements of the Virginia and New Jersey proposals.

The Great Compromise, which allowed the Constitutional Convention to continue, settled on a bicameral legislature. The House of Representatives would be based on population, hence appealing to the larger states, and the Senate would call for each state to send two representatives, which appeased the smaller states. Without jumping over the hurdle of representation in the new federal government’s lawmaking body, the United States Constitution’s ratification would likely never have occurred. Still, the success of the Great Compromise did not immediately resolve all of the issues the convention laid before its representatives. Although the founders showed their ability to find practical solutions to complex problems, this next one would prove even more difficult.

2. The Three-Fifths Compromise

The founding fathers knew better than to debate the moral implications of slavery, all unwilling to even call it by what it was and instead referring to it as the “peculiar institution.” Having to discuss the issue on moral grounds would no doubt leave the two vastly different geographical regions of the North and South unable ever to come together and form a unified nation; the delegates instead chose to tackle slavery as a calculated statistic.

The main issue was how to count enslaved people when determining a state’s total population for legislative representation and tax purposes. The argument that ensued and threatened to disrupt the proceedings showed the profound division between delegates from Northern states, where slavery was less prevalent or being abolished, and the Southern states, whose economy was heavily dependent on slave labor.

The delegates finally reached the Three-Fifths Compromise, which stipulated that each enslaved person be counted as three-fifths of a person for both representation and taxation purposes—a ratio previously used for tax assessments under the previous governing document, the Articles of Confederation.

While the compromise temporarily balanced the power between Northern and Southern States in the House of Representatives and allowed the eventual ratification of the Constitution, the incorporation of the three-fifths rule within the document implicitly acknowledged and legitimized the institution within the new government. In fact, the compromise only highlighted the deep-seated sectional divisions over slavery that would continue to plague the nation. It proved to be a temporary solution that did not address the moral and human rights issues at the heart of slavery. Yet, as far as the fifty-five delegates were concerned, their ability to compromise on complex issues had saved the day; the states ratified the US Constitution in 1788.

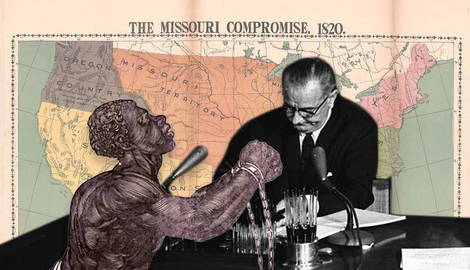

3. The Missouri Compromise

By 1819, even the so-called “Era of Good Feelings” following the War of 1812 could not deter the United States’ growing sectional disputes and conflicting opinions about slavery and its westward spread. Tensions finally reached a boiling point in 1819 when Missouri applied for statehood as a slave state, which threatened to disrupt the balance of power in the Senate, where, at the time, there was an equal number of free and slave states.

While the Southerners argued that the new states should have the right to determine for themselves whether to permit slavery and viewed the restriction of slavery’s expansion as a threat to their economic interests and social system, the Northern states foresaw more significant issues at hand. To representatives from the North, this was a question of whether slavery should expand westward into previously unoccupied lands. Admitting Missouri as a slave state would extend the institution of slavery into the Louisiana Territory and give the slaveholding South greater political power in the Senate, which would undoubtedly hinder any efforts to limit or abolish slavery further down the line.

Engineered by Henry Clay, a representative of Kentucky known to history as the “Great Compromiser,” the Missouri Compromise put a band-aid on the issue that threatened to split the nation apart. Missouri would be admitted to the Union as a slave state, but Maine was also admitted as a free state to maintain the balance in the Senate. This way, Clay ensured that the number of free and slave states remained equal and prevented either region from gaining a legislative advantage. The compromise also established a geographical boundary at latitude 36’30” north, the southern border of Missouri, which prohibited slavery in all territories of the Louisiana Purchase north of this line, except the just-added state.

The Missouri Compromise would have profound implications for the United States going forward. There is no denying that by maintaining the balance of power in the Senate, Clay’s plan set a clear line for the expansion of slavery, eased the ever-growing sectional tensions between the North and South, and addressed future admissions of states. Like the proceeding compromises of the Constitutional Convention, the Missouri Compromise demonstrated that compromise was not only possible but also necessary to maintain the Union. Still, while Clay managed to temporarily quell tensions, his plan only highlighted the deep and enduring divisions over the “peculiar institution.” The geographic line drawn by the compromise would come to symbolize the growing sectional divide, which would only deepen in the decades to come. Within thirty years, Congress would once more call on the elderly Henry Clay to try and mend the divided nation.

4. The Compromise of 1850

As the United States acquired new western territories following the Mexican-American War, the issue of slavery’s expansion once more threatened to tear the nation apart. Slavery took center stage in 1849, a year after gold was discovered in the newly acquired territory of California. Due to the region’s subsequent rapid population growth, the local legislation applied for statehood as a free state. The balance of power between free and slave states in the Senate once more hung in the balance.

Ever since the US Congress called upon Henry Clay to come up with a compromise in 1820, the situation surrounding the “peculiar institution” had become more complicated through the North’s growing anti-slavery (Abolitionist) movement. While the Southern states demanded stronger federal enforcement of laws to return escaped enslaved people, Abolitionist Movement proponents countered with the desire to see slavery eradicated not only in the nation’s capital but also disallowed in any new Western lands altogether, namely New Mexico and Utah.

Having quasi-retired seven years prior, Clay returned to Washington at the age of seventy-four, plagued with a terrible cough and early onset of tuberculosis, to once again mend the great divide between the two sections of what he called “this distracted and unhappy country.” So sick was the politician that it would be his colleagues who read his proposed compromise to the American Representatives. In what would become known as the Compromise of 1850, neither of the sides got what they truly wanted.

As future President James A. Garfield would remark about the event years later, “unsettled questions have no pity for the repose of a nation,” with the “good feeling” of the nation about its ability to compromise being as hollow and deceptive as it was in the 1820s.

The compromise saw California admitted to the Union as a free state, tipping the balance in the Senate in the free states’ favor—a victory for the anti-slavery North. The slave trade—albeit not slavery itself—was also deemed illegal in the nation’s capital. As for the territories of New Mexico and Utah, Congress permitted them to organize without restrictions on slavery. Instead, the settlers themselves would decide the issue of whether to allow slavery at a later date, a process known as popular sovereignty.

In return for the various concessions, the Southern states received a new, stricter Fugitive Slave Law that required citizens to assist in the recovery of escaped enslaved people and deny alleged fugitives the right to a jury trial. The law indirectly made slavery an American institution and not just a Southern one by stating that the North was no longer a place of refuge for escaped enslaved people as the Federal government would now ensure severe penalties on those who aided escapees and would have direct involvement in the capture and return of fugitives.

While Clay died only one year after his compromise, and while his newest band-aid temporarily resolved some issues, it ultimately intensified sectionalism beyond reproach. The strict Fugitive Slave Act particularly inflamed Northern public opinion against slavery. It led to increased support for the Abolitionist Movement and to significant political realignments that saw the weakening of the Whig Party and the creation of the newly dominant anti-slavery Republican party of the North, which got most of its votes from anti-Fugitive Slave Act proponents. Together with the failure of popular sovereignty in the Kansas territory, which led to bloodshed between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers, the effects of Clay’s compromise ultimately brought the nation to the Civil War in 1861.

5. The Compromise of 1877

A decade after the end of the Civil War and years since the passage of the 13th Amendment outlawing slavery, the nation was not yet done compromising on the long-debated question of what Thomas Jefferson meant when he wrote that “all men are created equal.” The Reconstruction Era, which followed the bloody conflict that pitted brother against brother, set off to rebuild the Southern states and integrate formerly enslaved African Americans into society as free citizens with equal rights.

The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 divided the South into military districts overseen by federal troops who enforced civil rights and ensured the protection of African Americans. Although the period saw the passage of both the 14th and 15th Amendments, the former granting African Americans citizenship rights and equal protection under the law and the latter granting African American men the right to vote, Reconstruction faced significant opposition from Southern whites who sought to maintain white supremacy and resist federal intervention.

Southern Democrats, known as “Redeemers,” set out to control state governments, restore pre-war social and political norms, and backtrack on the new rights and opportunities gained by African Americans. Their work of undermining federal policies, coupled with racial violence caused by new groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, received another boost in 1873 when the nation plunged into a severe post-war economic depression, which diverted attention and resources away from Reconstruction efforts. Over time, many Northerners, as much as most Southerners, grew weary of the ongoing political and social turmoil in the South and the financial cost associated with the military oversight needed to keep it going. The 1876 Presidential Election would become the harbinger of change—a time when it became evident that the pre-war, anti-slavery, and pro-Reconstruction Republican party had lost its sway with the American people.

The 1876 election saw Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes face off against the Democratic, anti-Reconstruction candidate Samuel J. Tilden in an election that saw the latter win the popular vote with 184 electoral votes, just one shy of the required 185, to the former’s 165 votes. To resolve the dispute, Congress established a bipartisan Electoral Commission consisting of fifteen members: seven Democrats and eight Republicans. When the dust settled, it would be another compromise over race and equality that saw the nation move forward, albeit, once again, not in the right direction.

The informal agreement between the leaders of the two political parties, later dubbed the Compromise of 1877, saw the Southern Democrats agree to accept Rutherford B. Hayes as the President of the United States in exchange for the withdrawal of federal troops from the South, effectively ending the federal government’s active enforcement of Reconstruction.

The nation was able to move on from sectionalist strife, all while leaving African Americans in the South vulnerable to disenfranchisement and racial violence without any federal protection. With the Republican Party no longer solely focusing on Southern issues, Southern states quickly enacted Jim Crow laws institutionalizing racial segregation and disenfranchising African Americans through methods such as literacy tests, poll taxes, and grandfather clauses.

The entrenched systemic racism and inequality that emerged from the time that followed the end of Reconstruction laid the groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement and the need for at least one more national compromise nearly a century later.

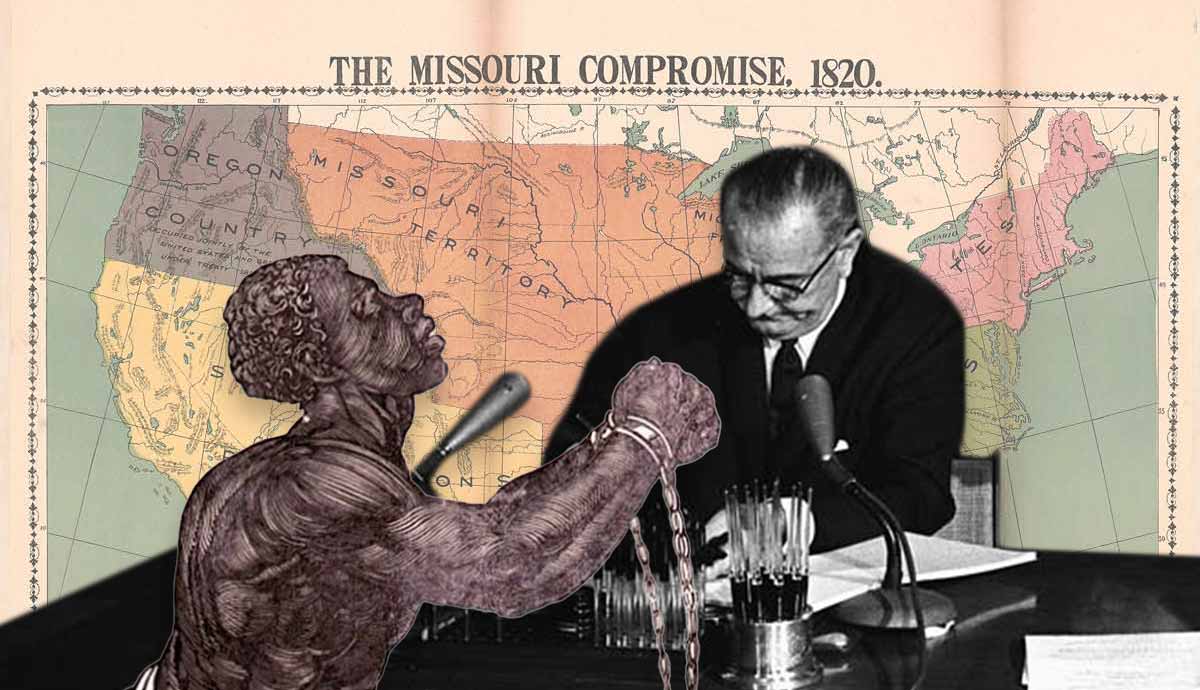

6. The 1964 Civil Rights Act Compromise

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s aimed to end racial segregation and discrimination against African Americans that stemmed from the Compromise of 1877 and the abandonment of the ideals championed by the Republican politicians of the time. Even though the court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954 declared separate schools for white and African American children illegal, segregation and discrimination persisted in all other aspects of southern life.

The now-famous Civil Rights Movement saw activists organizing protests, boycotts, and marches to demand equal rights and federal legislation to protect those rights. In response to the growing pressure from the movement, President John F. Kennedy introduced a comprehensive Civil Rights Act of 1964 to Congress shortly before his assassination. Once President Lyndon B. Johnson took over to see it come to fruition, it was evident that, like all other major political decisions in American history regarding race, this new one would once again require some political maneuvering and compromising.

Southern Democrats blocked the act’s journey through Congress through the usage of filibusters and other tactics to stifle it before it gained any traction. The legislation’s initial proposal addressed various forms of discrimination, including segregation in public places, unequal application of voter registration requirements, and discrimination in employment. While the bill passed the House of Representatives on February 10, 1964, it faced a formidable filibuster in the Senate. Southern Democrats, led by Senator Richard Russel of Georgia, argued that the bill infringed on states’ rights and individual liberties. The filibuster lasted seventy-five days, the longest in Senate history.

Its proponents agreed to several vital amendments and compromises to overcome the filibuster. Some provisions regarding public accommodations were modified and adjusted, and the bill’s provisions on employment discrimination were amended to include language to protect business groups against potential abuses of affirmative action. Lastly, amendments were made to the sections concerning desegregation of public schools and facilities, providing more time for compliance and addressing specific concerns from lawmakers.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, while undisputedly a step in the right direction, did not leave either party entirely satisfied. The act established important legal precedents for combating discrimination, provided a foundation for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and spurred further activism and advocacy for civil rights across various marginalized communities. It also contributed to a political realignment in the United States, with many Southern Democrats opposing the legislation, shifting allegiance to the Republican Party, and reshaping the political landscape for decades to come.

Like the compromises that came before it, all pivotal moments in American history that allowed the nation to move forward when the alternative spelled certain doom, the last political compromise about equality and justice never entirely closed the door on the issue. Yet, perhaps the Civil Rights Act of 1964’s most significant legacy is the reminder that even in modern times, the people of the United States of America are still capable of compromise.