The deep connection between walking and thinking recurs throughout human history. For Aristotle, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Jane Jacobs, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Nan Shepherd, walking was not simply a mode of travel—it was a crucial aspect of the life of the mind.

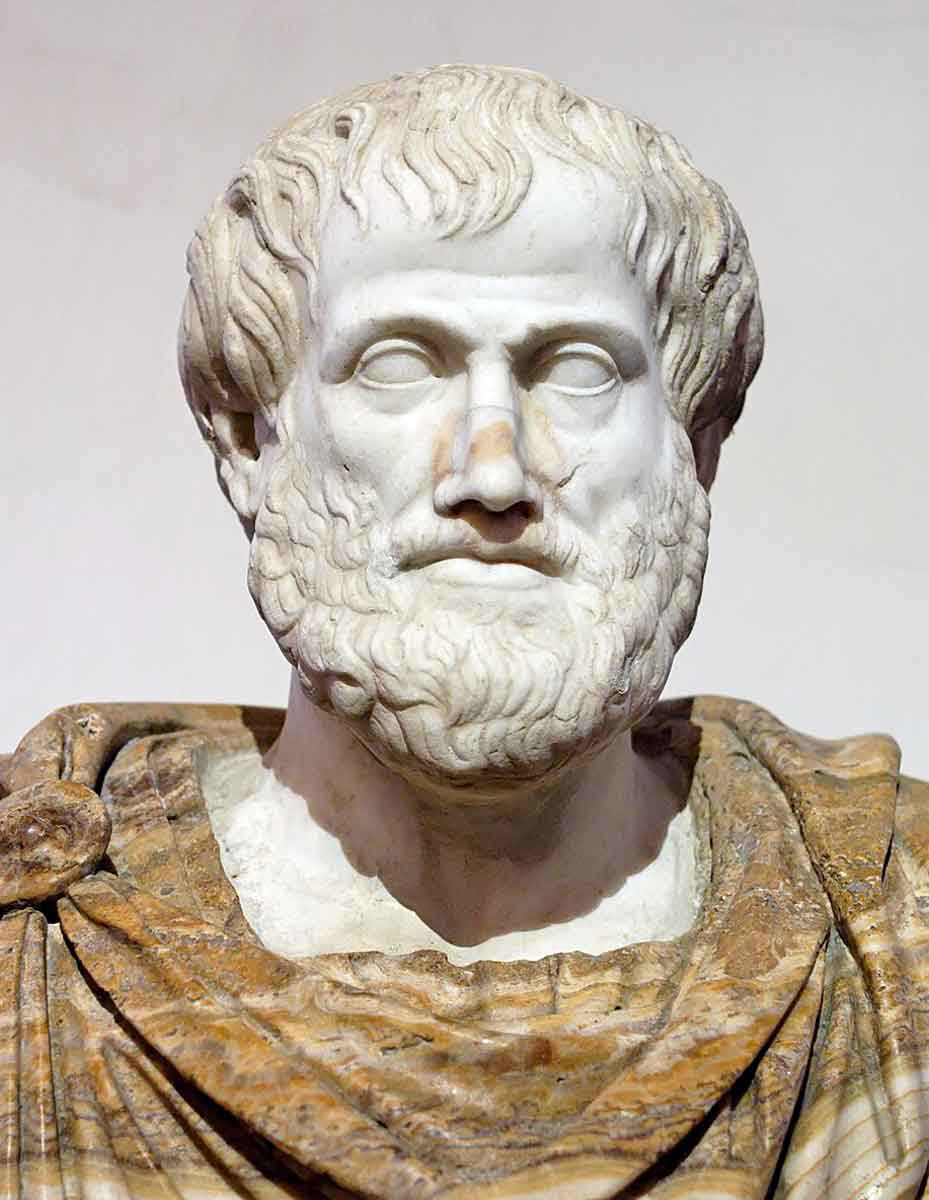

Aristotle: Peripatetic Philosopher

Aristotle, one of the most influential thinkers in the history of philosophy, laid the foundations of Western philosophy. A natural polymath, his contributions spanned an astonishing range of subjects—from logic, ethics, and politics to linguistics and the natural sciences. He was also a legendary walker.

Born in the northern Greek city of Stagira during the classical period, Aristotle moved to Athens around the age of 18 to study at Plato’s Academy, where he remained for nearly two decades. After Plato’s death, around 348/347 BCE, Aristotle eventually founded his own school in 335 BCE: the “Peripatetic School.”

Aristotle’s school became renowned not only for the quality and depth of philosophical inquiry but also for the distinctive method through which instruction was delivered. The name “Peripatetic” derives from the Greek word peripatētikos, meaning “given to walking about”—a reference to Aristotle’s habit of walking with his students as they engaged in deep philosophical discussion.

As a non-Athenian and thus unable to own property, Aristotle established his school in the public gymnasium and sanctuary known as the Lyceum, located on the city’s outskirts. The school quickly became known as the Peripatos, “the Walk,” due to its covered walkways and cloisters (Furley, 1999). According to the great biographer of Greek philosophers, Diogenes Laërtius, Aristotle would stroll these paths while engaging his students in philosophical dialogue.

It is thought that walking for Aristotle was more than a pedagogical style—it mirrored his method of inquiry, rooted in observation, continuous movement, and the pursuit of truth through dialogue. In this regard, over time, the term Peripatetic has come to refer not just to Aristotle’s teaching style, his famous school, and its architecture, but also to the practice of walking while engaging in philosophical thought itself.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Solitary Walker

Unlike Aristotle’s celebration of dialogue in motion, walking was more of a personal, introspective act for Jean-Jacques Rousseau. A hugely influential political philosopher, founding father of the romantic movement, and Enlightenment thinker, Rousseau produced highly influential works on inequality (Discourse on Inequality, 1754), education (Emile, 1762), and political legitimacy (The Social Contract, 1762).

However, his ideas were as controversial as they were influential. His critiques of organized religion, traditional education, and social inequality were seen as radical and potentially dangerous. In Emile, his vision of a “natural religion” free from church dogma led to charges of blasphemy. The Social Contract, with its argument that sovereignty belongs to the people, was viewed as subversive and dangerous by the political authorities of both church and state.

The backlash was swift and severe. Rousseau was condemned in France, where his books were banned and publicly burned. He faced arrest, was stripped of his citizenship in his native Geneva, and was forced into exile in Switzerland and later England. Isolated, denounced, and pursued by authorities, Rousseau lived much of his later life in a state of emotional and social exile.

Banned, exiled, publicly denounced, and forced into a life of instability and paranoia, he found refuge in a habitual fondness for long, introspective, solitary walks. His reflections were published posthumously as The Reveries of the Solitary Walker (1782).

In the ten essays that comprise the book, Rousseau reflects on his life, his thoughts, and a deep connection with the natural world. He found that in the rhythm of walking and deep silence of solitude, uninterrupted immersion in nature gained one access to a more authentic self, a pathway to clarity and emotional truth—unshaped by social artifice and free from the corrupting influence of civilization (Venkataraman, 2015).

Jane Jacobs: Walking in the City

Jane Jacobs was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1916. After moving to New York City during the Great Depression, she began professional life as a freelance journalist and rose to become one of the most influential urban thinkers of the 20th century. In 1961, she published her groundbreaking book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, a seminal critique of the prevailing wisdom of postwar urban planning.

Through her involvement in grassroots activism and her numerous writings, Jacobs famously took on the dominant paradigm of 1950s urbanism, represented by the Chairman of the New York State Council of Parks, Robert Moses—the urban planner behind New York’s mid-century redevelopment and the embodiment of modernist, grand-scale, car-centric urban design.

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs argued that modernist urban planning—dominated by highways, zoning, and uniformity—was destroying the social and economic fabric of cities. In several subsequent works, she redefined the conventional view of what makes cities thrive: urban space should be haphazard, diverse, and ultimately, walkable (Weingarten, 2016). For Jacobs, walking wasn’t just a personal or philosophical exercise; it was a vital component of modern urban life.

From her own neighborhood, Greenwich Village, Jacobs observed how the steady flow of pedestrians functioned like a kind of informal civic choreography, a “sidewalk ballet”—people watching one another, intervening when needed, and collectively shaping the social fabric of urban space (Jacobs, 1961). She viewed urban neighborhoods not as static zones defined by infrastructure or economic output, but as living ecosystems—complex, adaptive, and shaped from the ground up through the rhythms of everyday life.

Jane Jacobs viewed walking the city as the heartbeat of civic life, a way to keep the city honest, connected, and alive (Sassen, 2016). No matter how technologically advanced and digitally orientated our modern cities become, walking for Jacobs wasn’t just how we move through a city, but the way through which we come to know it, shape it, and ultimately, belong to it.

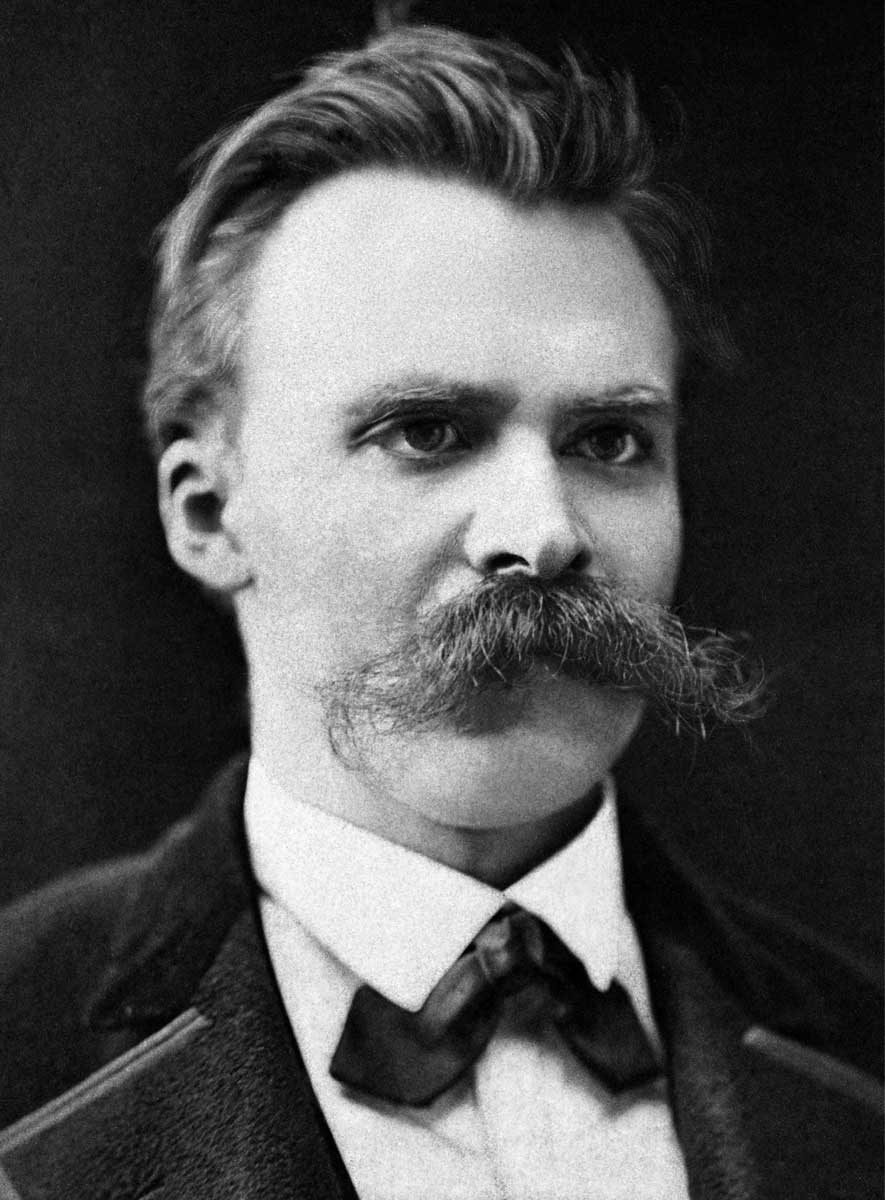

Nietzsche: Wandering Philosopher

Friedrich Nietzsche was a totemic philosopher of extraordinary influence. Yet he suffered from poor health most of his adult life. From his early 20s, he suffered from chronic migraines, visual disturbances, extreme fatigue, and severe gastrointestinal issues. Frequently bedridden for days, the intense physical suffering he endured deeply shaped his worldview.

Unable to write for long periods, Nietzsche composed much of his work in short bursts and aphorisms, between bouts of illness. When he felt well enough, he would walk prolifically—sometimes up to eight hours a day—both as a means of therapy and for purposes of creative stimulation.

Using his alpine cabin in the village of Sils-Maria in the Swiss Alps as a base, he regularly hiked for hours with his notebook and duly composed many of his greatest works on foot. Nietzsche saw walking not just as a habit, but as a means of achieving clarity of thought, living fully, and transcending conventional wisdom. “All great thoughts,” he wrote in Twilight of the Idols, “are conceived when walking.”

This belief finds its fullest expression in Thus Spake Zarathustra, where his protagonist, Zarathustra, repeatedly ascends and descends a mountain in his quest to become a sage, moving between the solitude of his cave and the bustle of human society. After ten years of reflective solitude, Zarathrustra chooses to wander from town to town, rather than settle in one place, engaging in dialogue, questioning, and observing before retreating again into the wilderness.

Accordingly, Nietzsche presents life as a Weg—a path one must walk individually. His concept of the Übermensch (Overman) is not a final destination but a direction of growth. Walking, in this regard, symbolizes the noble refusal to be fixed in place—the refusal to remain stationary, both physically and philosophically. Moreover, as a metaphor for life, it represents the courage to forge one’s own path, unbound by custom and the inherited values of civilization.

Nan Shepherd: Literary Rambler

Anna “Nan” Shepherd was born in a small cottage near Aberdeen, Scotland. She began her career as a writer with a trilogy of three novels: The Quarry Wood (1928), The Weatherhouse (1930), and A Pass in the Grampians (1933), establishing herself as a key figure in the development of 20th-century Scottish literary modernism.

She spent most of her working life as a lecturer of English at the Aberdeen College of Education, while spending as much time as she physically could, immersed in the landscapes of the Scottish Highlands. A formidable hill walker, “rambling” through nature was central to Nan Shepherd’s life, writing, and thought. It enabled her to enter into a deeper relationship with the natural world—and with herself.

As a woman walking and writing about nature in the 1940s, she was unusual—the field being dominated by male explorers. Yet, as early as 1940, she journeyed on foot deep into the Cairngorms. She spent decades on and off, merely walking, observing, and listening. Shepherd claimed above all to explore the mountains not as a conquest, but as an intimate companion.

Deeply attentive to nature and landscape, she described her routes through the ancient Caledonian forest as an “unpath,” of wind and mist, lichen-slick granite and purple heather. The great outdoors, for Shepherd, was a profoundly sensual experience: not just an external terrain but an inner landscape (Bell, 2013).

In 1945, she wrote The Living Mountain, part memoir, part field study of her experiences. A true masterpiece of nature writing, travel writing, and philosophical reflection (Bell, 2013), her prose mimics the rhythm of walking: measured, attentive, lyrical. The way she writes mirrors the way she moves: slow, thoughtful, observant.

Nan Shepherd wrote beautifully of “being with” the mountain rather than ascending it—inviting the reader to see the mountain not as an object to be understood, but as a relationship to be entered into and discovered. She walked “not to escape the world, but to join it” (Shepherd, 1977).

Bibliography

Bell, E., 2013. Into the Centre of Things: Poetic Travel Narratives in the Work of Kathleen Jamie and Nan Shepherd. In: R. Falconer, ed. Kathleen Jamie: Essays and Poems on Her Work. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp.126–133.

Furley, D., ed., 1999. From Aristotle to Augustine: Routledge History of Philosophy Volume 2. London: Routledge.

Jacobs, J., 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Sassen, S., 2016. How Jane Jacobs changed the way we look at cities. The Guardian, [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/may/04/jane-jacobs-100th-birthday-saskia-sassen [Accessed 28 May 2025].

Shepherd, N., 1977. The Living Mountain. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press.

Venkataraman, P., 2015. Romanticism, Nature, and Self-Reflection in Rousseau’s Reveries of a Solitary Walker. Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, 11(1), pp.327–341.

Weingarten, M., 2016. Jane Jacobs, the writer who changed the face of the modern city. The Guardian, [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/sep/21/jane-jacobs-modern-city-biography-new-york-greenwich-village [Accessed 28 May 2025].