The art of ancient Rome stands as a testament to the power of cultural exchange, particularly in the realm of sculpture. From lifelike portraits of emperors to mythological statues adorning luxurious villas, Roman artists borrowed, adapted, and transformed Greek style into something uniquely their own, achieving a seamless fusion of idealism and realism that not only defined Roman art but also served their own cultural and political needs. This article explores the Greek origins of classical Roman statues, examining their impact on Roman portraiture and sculptural representations of villas.

Greek Influence on Roman Art of Portraiture

The Greeks, particularly during the Classical period (5th–4th century BCE), developed an artistic tradition that celebrated idealized human forms. Statues of gods, athletes, and philosophers embodied a high level of physical and psychological balance through a strict adherence to symmetrical proportions, harmonious compositions, and a pursuit of beauty and inner equilibrium rendered through mathematical precision. This approach was meant to convey the concept of arete (ἀρετή), or excellence, embodying both physical perfection and intellectual virtue.

Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) is one of the most influential sculptures from the Classical Greek period. Created around 440 BCE, this statue represents a young, athletic male figure who epitomizes the Greek ideal of physical perfection and mathematical harmony. Polykleitos, indeed, designed the Doryphoros based on the principles and ideal proportions established in his treatise, the Canon, according to which the ideal human can be represented using accurate mathematical ratios. This sculpture not only became the quintessential example of Greek art but also became a foundational model for Roman copies and adaptations. In particular, Romans were inspired by its contrapposto stance, where the weight is shifted onto one leg, as this pose added to the sculpture a naturalistic sense of balanced movement.

In the realm of portraiture, Roman sculptors adapted this Greek tradition and progressively increased the element of realism to reflect their own societal values and agendas. While the early Roman Republic adhered more closely to Greek-inspired idealism, the late Republic progressively enhanced the realistic element of the representation, insofar as reaching a style known as verism. This hyper-realistic style emphasized individual characteristics, including wrinkles, scars, and imperfections, to facilitate recognition, to convey wisdom, experience, and virtue—key attributes of Roman leadership. Towards the Imperial period, instead, a blend of the two was used to create portraits that balanced idealized features with individualized details.

Political Propaganda in Busts and Statues

Roman portraiture had a distinct political function, often serving as propaganda for leaders and aristocrats. Unlike the Greeks, who sculpted generalized and deified representations of human figures, Romans, particularly during the late Republic, developed a tradition of commissioning lifelike busts that showcased their distinct features, personality, and achievements, serving as political tools to secure authority, legitimacy, and legacy.

The facial features of the Tivoli General by Phidias, for instance, exemplify the veristic style that characterized late-Republican sculpture. The figure is represented with deeply etched wrinkles, sunken cheeks, and a receding hairline; features that emphasize his age, experience, and military leadership. His body, however, displays the blend of Greek idealism and Roman realism that will become even more prominent in the Augustan age, when features were increasingly individualized yet idealized at once.

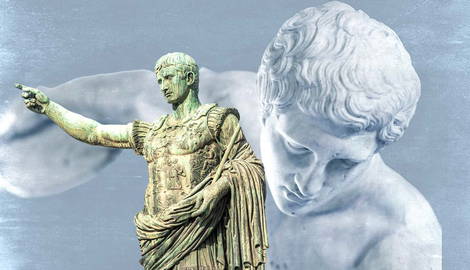

Augustus himself was frequently depicted with personal, yet always youthful and flawless features, a deliberate departure from the detailed verism of earlier Republican leaders. The Augustus of Prima Porta is one of the most iconic statues of the first Roman emperor to showcase this stylistic blend. The emperor is represented at the peak of his youth as a powerful, godlike ruler of Rome. His detailed cuirass (breastplate) portraying a diplomatic victory reinforces his role as a military leader and bringer of peace, while the small figure of Cupid at his feet symbolizes his divine lineage, linking him to Venus and legitimizing his divinely ordained rule. These details reinforced the ideal state of Augustus’s divine status and positioned him as the inheritor of Greek knowledge while establishing a unique precedent for the artistic identity of Imperial Rome.

Greek Influence on the Sculptures for Roman Villas

Greek influence extended beyond portraiture. For instance, its influence can be noticed in the architectural and decorative schemes of Roman villas. In particular, during the Imperial period, a Greek artistic revival known as the Neo-Attic style emerged, which sought to directly imitate Greek Classical and Hellenistic art, producing sculptures that closely resembled earlier Greek works. Wealthy Romans were integrating Greek artistic motifs into their residences and gardens. These sculptures—representing athletes, gods, mythological heroes, and legendary figures—were generally placed in the peristyle garden, a common feature in Greek homes that was widely adopted in Roman villas. These sculptures served both a decorative and symbolic function, reinforcing the cultural and intellectual aspirations of the villa’s owner.

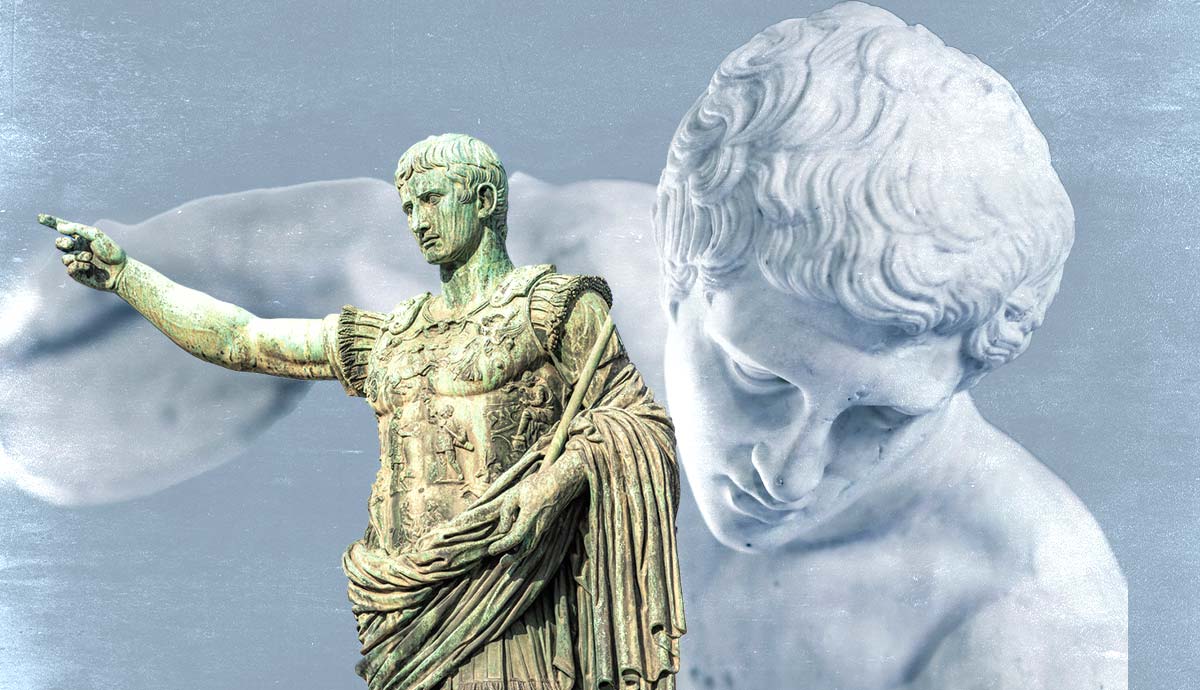

Roman emperors such as Hadrian (117–138 CE) were particularly enamored with Greek culture. They sought to emulate the sophistication of Greek aristocracy by commissioning extensive collections of Greek-inspired sculptures for their villas. His Villa at Tivoli, one of the most famous Roman estates, is a prime example of Greek influence on Roman villa decoration.

Mythological Sculptures

Sculptures for the Roman Villa frequently depicted Greek deities and mythological themes, reflecting both admiration for Hellenistic culture and a desire to project sophistication and erudition. Statues of Apollo, Venus, and Hermes, among others, were commonly found in gardens, fountains, and atriums, serving not only as decorations but also as cultural symbols linking the homeowner to the ideals of beauty, intellect, and divine favor. These sculptures paid homage to the Greek pantheon and its rich, symbolic mythology.

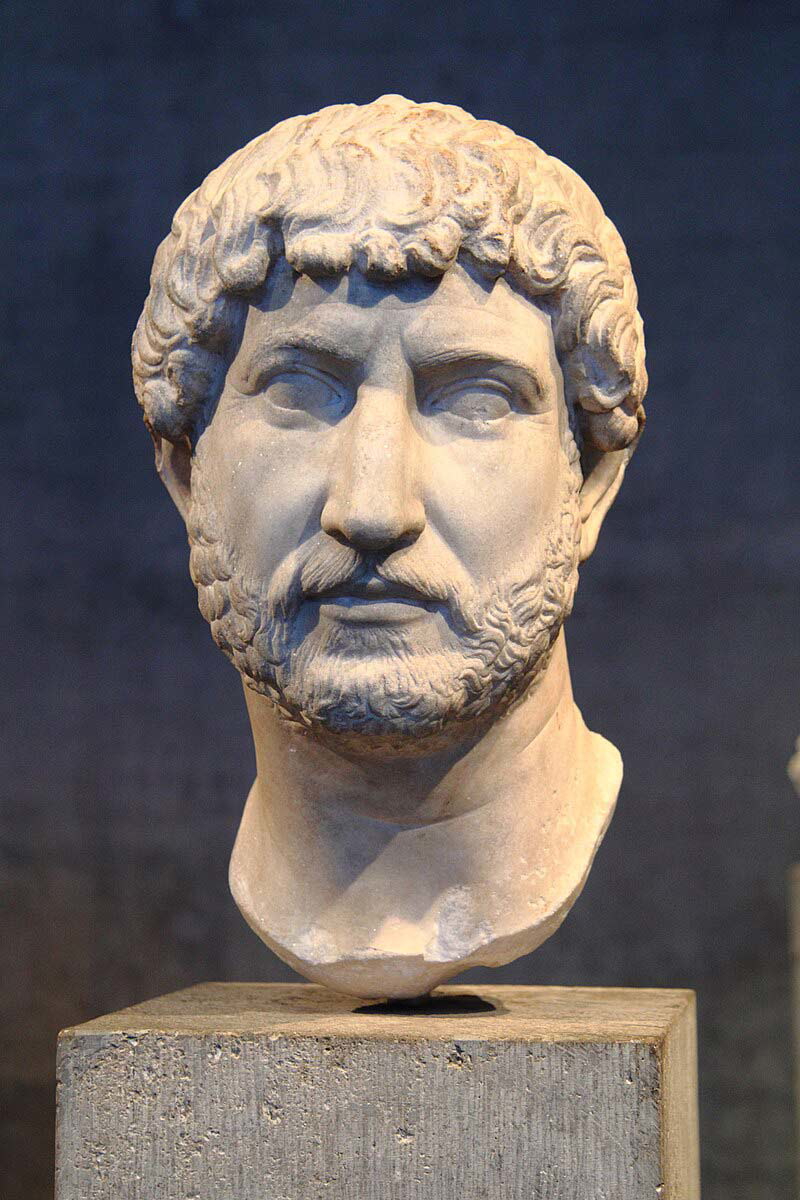

In addition to traditional gods and heroes, Romans were deeply fascinated by mythological hybrids. Creatures such as centaurs, satyrs, sphinxes, and the Hermaphroditus, a figure embodying both male and female characteristics. These fantastical beings, or dual-sexed bodies, symbolized themes of transformation, duality, and the boundaries of human experience. For the Romans, such figures were not only exotic and visually striking but also intellectually stimulating, offering a way to explore deeper philosophical and cultural questions about identity and a way to explore philosophical and moral themes within the safe context of mythology.

Mythological sculptures were strategically placed to reinforce the purpose of the space in which they were displayed. For instance, statues of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and revelry, were often placed in dining rooms, whilst depictions of nymphs, tritons, and sea creatures were often used to adorn fountains and enhance the dynamism of the water.

Athletes

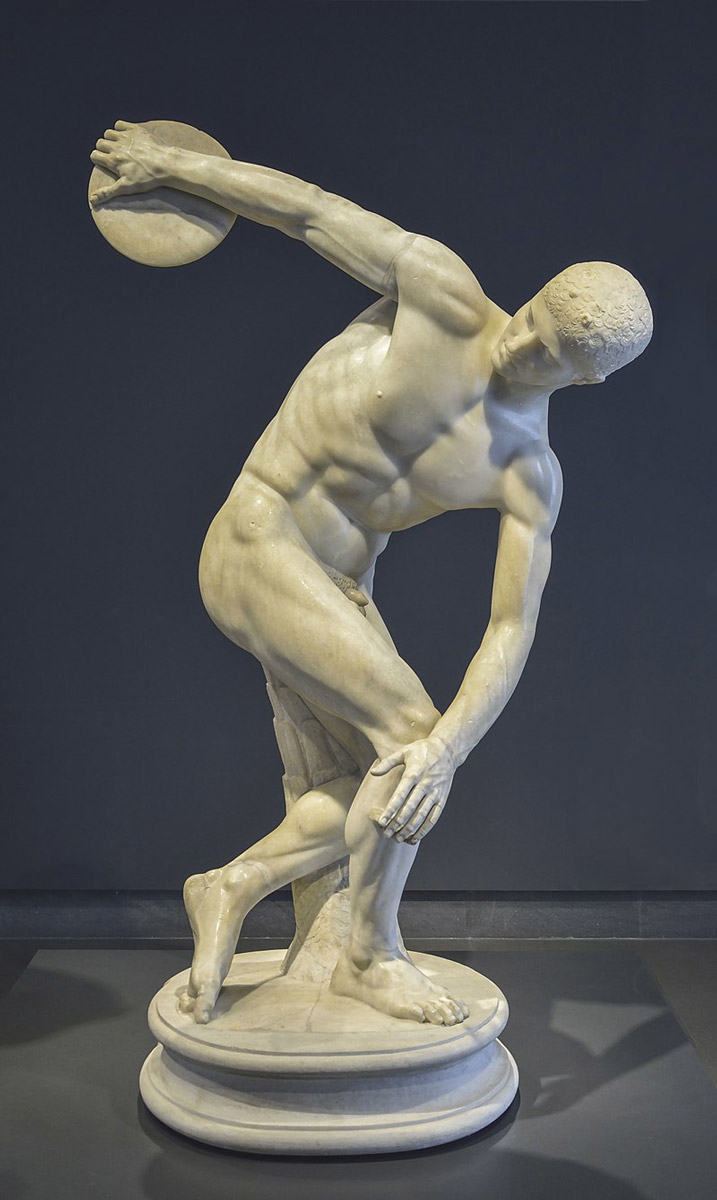

Greek-inspired representations of athletes were a prominent feature in Roman villa decoration, reflecting admiration for Greek physical ideals, competitive spirit, and philosophical associations with the disciplined body. Greek statues of athletes originally served to celebrate victory, virtue (aretē), and the divine harmony of the human form. The Romans, eager to connect themselves with this cultural heritage, brought such imagery into their private spaces.

In Roman villas, sculptures of discoboli (discus throwers), wrestlers, and runners were strategically placed in peristyles, baths, and gardens. These statues often echoed the dynamic yet balanced poses of Greek originals, such as Myron’s Discobolus or Lysippos’ agile figures, and conveyed not only physical strength but the inner discipline required of an athlete. They also served a didactic function, reminding viewers of the virtues of self-control, training, and moral integrity.

Philosophers

In addition to gods, heroes, and athletes, Roman villas often featured sculptures of Greek philosophers, underscoring the Roman elite’s admiration for Greek intellectual traditions. These statues were more than mere decorations. They served as powerful symbols of wisdom, moral virtue, and cultured identity. By surrounding themselves with the likenesses of revered thinkers such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Epicurus, Roman patrons aligned themselves with the ideals of rational thought, ethical living, and philosophical inquiry.

These sculptures typically depicted philosophers in a contemplative or teaching posture: seated or standing with scrolls, cloaks, and beards that marked them as wise intellectuals. Unlike the idealized physiques of gods and athletes, philosopher statues often portrayed aged figures with lined faces and thoughtful expressions, embodying a life of study and introspection. This deliberate realism conveyed gravitas, a Roman virtue that emphasized seriousness, dignity, and depth of character.

From Imitation to Innovation: How Greek Statues Shaped Roman Art

The Greek origins of classical statues profoundly shaped Roman artistic traditions, particularly in portraiture and in villa decorations. While Roman artists borrowed heavily from Greek ideals of beauty, they also adapted these influences to reflect their own cultural, political, and personal aspirations. By preserving and adapting Greek artistic principles, the Romans not only paid homage to their Hellenistic predecessors but also forged a distinctive artistic vocabulary that would influence Western art for centuries to come. The interplay between Greek and Roman artistic traditions remains a testament to the enduring power of classical aesthetics, reflecting a cultural dialogue that continues to inspire art and architecture to this day.