After centuries of progress and development, Greek sculpture reached its “final” form during the Hellenistic Age, usually dated from Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BCE. Around the 1st century BCE, Greece was incorporated into the Roman Empire, ushering in a new period of Greco-Roman art, which was largely a continuation of the Hellenistic form. During the Hellenistic period, the Greek worldview on art shifted from the perfect ideal of the Classical period to more realistic and mundane subjects, a move that is highly influential in modern art.

What Is the Hellenistic Age?

In 336 BCE, Alexander the Great ascended to the throne of Macedon upon the death of his father, Philip II. The next 13 years of his reign were spent on a meteoric rise in power and prestige, conquering the Persian Empire and expanding Greek culture and influence east. Upon his death in 323, the Macedonian kingdom stretched from the Balkans to India.

The Hellenistic Age is generally believed to have begun with Alexander’s death. The lands brought to heel by the Macedonian phalanxes fractured without a strong central leader, and the territories were broken up into several smaller successor states. These kingdoms maintained the Greek cultural sphere over vast territories, and while they influenced the local culture, this was far from a one-way cultural exchange.

Greek art during this era evolved dramatically. The first Greek art form to emerge after the Bronze Age Collapse was the Geometric period, which featured highly stylized depictions of human and mythological forms. This gave way to more naturalistic statues during the Archaic Era, which saw the emergence of more realistic but still unnaturally rigid human forms. During the Classical Era, the emphasis was more on anatomical realism, but this realism was tempered by the subject matter. Classical Greek art almost exclusively depicted humans in the most ideal form, with the primary subject being fit young men in the heroic nude. During the Hellenistic era, statues exhibited a wide array of subjects, such as young and old men, women, and common people, all experiencing extremes in emotion that had not been seen before in Greek art.

Extremes of Emotion on Display

During the Classical era, Greece was at its highest point in terms of cultural expression. After throwing off the Persian threat, the Greek world was buoyed by a newfound optimism, leading to a golden age of culture. Their art reflected this, and the main theme of their work was that of the ideal. With few exceptions, statues were of young men at the peak of human perfection, their faces blank yet serene, avoiding any extremes in emotion. By the end of the era, right before Macedonian domination, this was already beginning to shift.

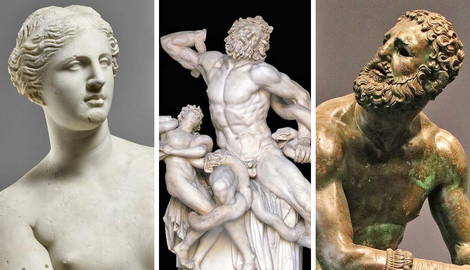

Statues with emotionless expressions continued to be made, though, in the Hellenistic era, these were soon joined by statues that expressed a wide range of human feelings. These could be joy, sorrow, anger, agony, or contentment, all of which were reflected in not only expression but also posture. Faces were captured at the height of emotional moments. This was the first true attempt to convey this part of the human experience in Greek history, outside of the vague Archaic smile found on Kouroi and Korai. Statues were also painted and decorated with gems, mother of pearl, or bone inlays for eyes, and given jewelry, wreaths, or weapons, which only accentuated the lifelike quality of the piece.

The Boxer at Rest is a rare surviving bronze statue, since the metal was often melted down and reused. Discovered in 1885, it shows an older athlete, nude except for his leather hand wraps, in a posture of exhaustion and resignation. His face is one of agony, with bruises, sunken lips, and a slightly open mouth, combined with his seated position and slumped shoulders, expressing a combination of exhaustion, pain, and vulnerability. His cauliflower ears, a common affliction among combat athletes even to this day, imply that this is an aging athlete at the twilight of his career, not an idealized boxer in the flower of youth, themes unheard of in earlier eras.

Attention to Detail and Anatomy

As the ages passed, Greek artists perfected the depiction of the human form with increasingly greater detail. Geometric era art was too stylized for any detail, and the Archaic era was more naturalistic but still too rigid for the statue to appear lifelike. During the Classical era, the art of nearly anatomically accurate figures began to be developed, showing the musculature and posture of the subject as realistically as possible. One key feature of the Classical era that was copied and perfected during the Hellenistic era was the concept of contrapposto.

Contrapposto, an Italian word meaning counterpoise, was a term coined centuries later to describe a human figure that is standing rigid but has most of its weight on one leg, twisting the hips, shoulders, and spine while also staggering the legs in a fluid way. This can be found in sculptures, statues, paintings, or any other medium where the human body is depicted. There were some examples in the Archaic era, though it became an established trait during the Classical era. During the Hellenistic era, contrapposto became the standard by which virtually all statues were made.

A number of statues were also “draped” or depicted with clothing, and the clothing was carved in such a way to give a sense of movement or dynamism. The Winged Victory of Samothrace shows the goddess Nike landing on the prow of a ship. Her body is jutting forward, her clothing and wings being forced backward, giving a distinct impression of flight. The statute captures the instant she touched down on the ship’s deck. Though clothed, Nike’s anatomical details are still visible underneath the cloth, and the work showcases distinct attention to detail in both anatomy and movement.

A Wide Array of Subjects

The Classical era’s fixation on depicting their culture’s ideal limited the subject matter to young men heroically nude, triumphant after a glorious achievement, or simply reveling in their perfection of youth and beauty. The Hellenistic era changed this dramatically, with older men as the subject, as well as children, women, and mythological beings in various emotional and physical states. With the emphasis no longer on perfection but rather on reality as it was, some subjects, such as the old or crippled, were shown, their anatomical features showing the harsh realities of life. Likenesses of fishermen, peasants, craftsmen, beggars, drunkards, and other lower-class members of society were depicted in great detail.

Women were also depicted much more frequently than before. Female figures, usually goddesses, have always been depicted for religious devotion, and these were almost always clothed. The first nude female statue is believed to be the Aphrodite of Knidos, which was made at the end of the Classical era. During the Hellenistic era, nude female statues became much more common. Perhaps the most famous is the Venus de Milo, made in the 2nd century BCE. What makes this statue unique is the obvious erotic nature of the subject. The ancient Greek world viewed nudity much differently than the modern world, and even the Aphrodite of Knidos is far less sexualized. It is clear, though, by the posture and expression on the statue’s face, that the Venus de Milo is enticing the viewer with a degree of sexuality and eroticism that was unheard of in earlier eras. The erotic nature would have been accentuated with the sculpture painted and adorned with jewelry.

Telling a Story

Throughout history, statues were usually of individual figures. These could be deities, athletes, or some other singular figure for devotion or admiration. This practice continued in the Hellenistic era, but this was supplemented by the use of statues to tell a narrative. Statues would sometimes be displayed in groups, each one telling a segment of a larger story. The tales shown were often mythological in nature and included scenes from epic poetry, cautionary tales, or historical events.

One of the most famous masterworks of the era is Laocoon and his Sons, which depicts a scene from the Trojan War. Made from a single piece of marble, this work features three human figures, all of whom are in the throes of agony. In mythology, Laocoon was a priest of Troy who wanted to warn his fellow Trojans about the ruse that was the Trojan Horse. To prevent this warning, the gods sent serpents to kill him and his sons. The piece shows the three human figures, the mature Laocoon and his two youthful sons, desperately fighting off snakes that are both constricting and biting them. The agony and terror on their faces are evident and palpable; limbs are stretched, muscles tense, and bodies bent in torment. There is no ambiguity about what emotions or themes the artist was trying to convey.

Even moments of triumph are given more complexity than they may initially seem. The Dying Gaul is a statue commemorating a Greek victory against the Gallic barbarians. The Gaul is recumbent on his side, with a wound to the chest and blood spilling out. Another statue discovered at the same time was the Gaul Committing Suicide with his Wife, in which another Gallic warrior drives a blade into his shoulder, his wife slumped in his arm at his side. Though these were made to demonstrate the Greek world’s superiority against the Gallic barbarians, the viewer cannot help but be moved to pity seeing the men’s faces contorted in pain, resigned to their fate, yet still defiant in the face of inevitable death.

The End of the Hellenistic Era and Its Sculpture

The Hellenistic age began with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE and continued for about three hundred years. Most scholars date the end of the age to the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, when Octavian won the decisive battle of a Roman civil war and established control over the Hellenistic kingdom of Ptolemaic Egypt. Of course, history does not have such clearly defined turning points, and some scholars believe that the era lasted much longer, well into the 2nd century CE, at least in the realm of culture and artistic expression.

In an ironic twist of fate, the conquerors of the Greek world, the Romans, actually helped preserve the artistic achievements of their vanquished foes. The Romans loved Greek culture and adopted many aspects of Greek tradition, including art. Many of the surviving statues to this day are not originals, but rather much later copies made by the Romans. Though, officially, the Hellenistic age was at an end, and the dominance of Greek culture throughout the ancient world was replaced by Roman hegemony, the techniques mastered over the centuries continued on well into the Roman Empire. When Rome began to crumble, the artistic quality suffered as well, and the sophistication of Greek statue design fell by the wayside.

Greek art, as it is known today, began in the aftermath of the Greek Dark Ages, which occurred after the Bronze Age collapsed. When the Western Roman Empire fell in the late 5th century, Europe was likewise gripped with cultural stagnation. While it would be unfair to say that there were no cultural innovations, Western art was only able to reach levels of sophistication after the Renaissance, which saw a rediscovery of ancient techniques pioneered centuries prior, including those of the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic age Greece.