During the Hellenistic and Classical periods, ancient Greek sculpture aimed to depict the human form realistically, but in an idealized and harmonious state. Greek Sculptors studied anatomy and sought to capture physical perfection and inner vitality. They believed that the human body reflected divine beauty, and sculpture was a medium through which to express this belief. Let’s explore how sculpture evolved and highlight some key masterpieces.

Attic Grave Monuments

Attica, the region surrounding Athens, developed distinctive burial rites and intricate grave markers. In the 5th and 4th centuries BCE, Attic grave monuments honored the deceased, reflected social status, and marked burial sites with artistry. The most common type in the 5th century BCE was the stele—a tall, upright slab of stone or marble. These stelae showcased artistic skill and detailed motifs like farewells, children with pets, and battle scenes, all celebrating the virtues and legacy of the deceased and their families.

In the 4th century BCE, a shift occurred in the design of Attic grave monuments. The stelae began to incorporate architectural elements, such as triangular pediments, columns, and small temples. This architectural approach created an even more elaborate and exquisite appearance for the grave monuments. The sculptural decoration also became more complex. Artists began to depict scenes from everyday life, such as banquets, hunting scenes, or the deceased engaging in athletic activities. These scenes aimed to reflect the interests and accomplishments of the dead and provide a glimpse into their idealized lives.

Architectural Sculpture

Architectural sculpture played a central role in ancient Greek art and architecture. Found on temples, public buildings, and homes, sculptors used it to beautify structures, tell mythological stories, and express religious and cultural values.

Key architectural elements with sculptural decoration included:

- Metopes are rectangular spaces between the triglyphs on the Doric frieze of a temple. They were often decorated with relief sculptures depicting various mythological or historical scenes. Metopes were typically carved in high relief, creating a sense of depth, narrativity, and three-dimensionality.

- Pediments are the triangular spaces at the ends of a temple. Pediments were excellent locations for sculptural compositions. The pediments featured complex relief sculptures portraying mythological narratives or significant events related to the temple. The sculptures in pediments often pictured gods, goddesses, heroes, and mythological figures.

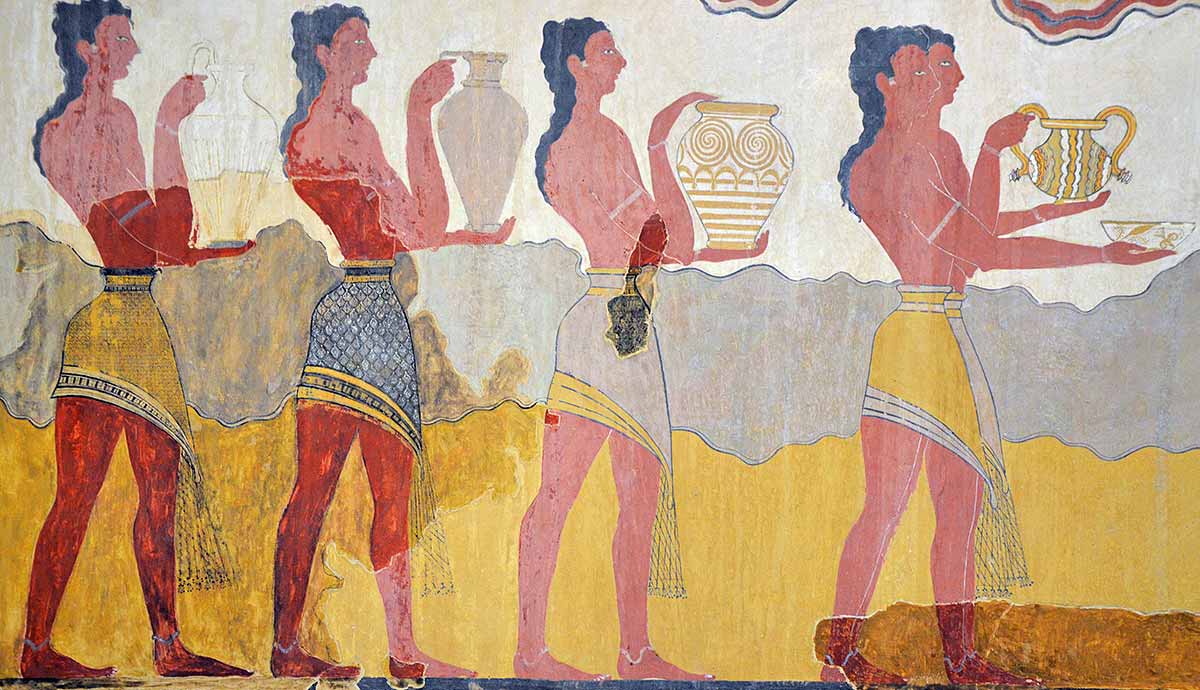

- Friezes are decorative bands located above the architrave of a temple. There were two main types: the Doric frieze and the Ionic frieze. The Doric frieze was characterized by alternating triglyphs and metopes. The metopes could contain relief sculptures, as mentioned earlier. The Ionic frieze, found in Ionic order temples, was a continuous band of relief sculptures depicting various subjects, including processions, rituals, and scenes from daily life. The Parthenon of the Acropolis had a frieze depicting a Panathenaic procession, which circled the temple.

- Caryatids are sculpted female figures used as architectural supports, often as columns. They were typically depicted wearing draped clothing and standing in a contrapposto stance, which created a sense of movement and grace. Caryatids were commonly found in the Ionic order and were named after the city of Caryae.

- Acroteria are decorative elements placed on the corners of pediments, as well as on the corners of roofs. Later, Gothic architects copied them, so they now appear on buildings from different eras.

Honorific Statues

Honorific statues and their bases are an important aspect of ancient Greek art and culture. They commemorated prominent citizens, military leaders, athletes, and other individuals who made significant contributions to society. These statues stood in sanctuary courtyards and city squares, symbolizing honor, prestige, and the pursuit of excellence.

Crafted in marble or bronze, these statues emphasized idealized versions of the honored individuals rather than realistic likenesses. Sculptors used the lost-wax technique for bronze and hand-carving for marble.

Honorific Statue Bases: Important Clues

Far more bases survive today than the honorific statues they once supported. These square or rectangular platforms raised statues for visibility and often held multiple figures as a visual ensemble. Their inscriptions name individuals, detail accomplishments, and credit sculptors, patrons, and divine dedications. They offer critical insights into personal histories and ancient Greek social dynamics.

Honorific statue bases can also feature decorative elements such as relief sculptures or architectural embellishments. These decorative elements could include scenes related to the honored person, symbols of their achievements, or mythological motifs. Artists added these embellishments to enhance the beauty and significance of the monuments, which visitors often overlook during their museum visits.

Roman Copies: Not Always Replicas

Most original Greek statues were lost over time. Fortunately, Roman artists preserved them by creating copies. These versions covered gods, athletes, heroes, and everyday people, ensuring Greek artistic traditions endured. Often carved in marble, Roman copies survived longer than the bronze originals, which were commonly melted down for coins or weapons. Roman artists didn’t always make exact replicas. Emperors and elites often commissioned them to display cultural refinement and reinforce their status. Over time, Roman sculpture evolved toward naturalism, with subtle shifts in expression, posture, and texture marking a departure from Classical idealism.

Greek Sculpture of the Classical Era

The Classical era of the 5th century BCE emphasized harmony, ideal beauty, and perfect proportions—principles that deeply influenced Western art. Greek sculptors combined realism and anatomical precision to portray the human form in its most balanced, ideal state. One defining technique was contrapposto, where a figure’s weight rested on one leg, creating a natural, relaxed stance. These sculptures conveyed calmness and dignity. Serene facial expressions, detailed musculature, and fluid drapery all showcased technical skill.

Sculptors carved gods, heroes, and notable citizens—mostly in marble, although bronze was also commonly used. These statues filled temples and public spaces, expressing civic pride and religious devotion. Renowned sculptors like Phidias, Myron, and Polykleitos set the artistic standard. Works like the Parthenon sculptures and the Discobolus (also known as the Discus Thrower) are iconic representations of Classical Greek art.

Greek Sculpture of the Hellenistic Era

The Hellenistic era, which spanned from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE to the establishment of the Roman Empire in 31 BCE, witnessed a significant evolution in Greek sculpture. During this period, Greek art experienced a shift in style and subject matter, reflecting the cultural, political, and social changes of the time.

Hellenistic sculpture diverged from the idealized perfection of the Classical period, adopting a more emotional and dramatic approach. Sculptors sought to convey intense emotions, extreme narratives, and new levels of detail in their works. The statues often depicted dynamic poses, exaggerated gestures, and complex compositions that captured movement and energy.

One characteristic feature of Hellenistic sculpture is the exploration of diverse subjects and themes. Artists moved beyond the traditional focus on gods and heroes to depict ordinary people, children, elderly individuals, and animals. This expansion of subject matter allowed a greater range of expressions and emotions to be conveyed, making the sculptures more relatable and humanistic.

The Hellenistic period also saw advancements in sculptural techniques and materials. Sculptors experimented with new materials and explored their potential for realism and expressiveness. They excelled at bringing out details, such as skin, hair, and clothing textures, as well as the rendering of emotions through facial expressions and body language. Masters like Lysippus, Praxiteles, and Scopas pushed aesthetic boundaries, celebrating individuality, inner life, and the complexities of the human form.

9 Key Ancient Greek Sculptures

1. Nike of Samothrace

This stunning marble sculpture, dating from the 2nd century BCE, depicts Nike, the Greek goddess of victory. The statue captures the dynamic movement of Nike with her billowing drapery, conveying a sense of triumph and grace. The sculpture is now displayed in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

2. Aphrodite of Knidos

Created by the Greek sculptor Praxiteles in the 4th century BCE, this sculpture depicts the goddess Aphrodite, the embodiment of beauty and love. Art historians consider it one of the first significant depictions of a fully nude female form in Western art. Although the original is lost, several Roman copies and adaptations reveal its appearance and lasting influence. There are several copies in museums, such as the Louvre, the Uffizi Gallery, and the British Museum. Still, the one closest to the original is usually considered to be in the Vatican Museum.

3. Hermes of Praxiteles

Another work attributed to Praxiteles, this sculpture captures the god Hermes holding the infant Dionysus. The delicate forms and the tender interaction between the two figures make this sculpture a masterpiece. The statue was discovered during excavations of the Temple of Hera in Olympia in 1877 and is now on display at the Archaeological Museum of Olympia.

4. The Riace Bronzes

This pair of larger-than-life bronze sculptures, created around 460-450 BCE, depicts two ancient Greek warriors. The sculptures are magnificent examples of the sculptor’s ability to display details of the warriors’ anatomical features and facial expressions. Archaeologists discovered the statues in Riace, Italy, and the National Museum of Magna Grecia in Reggio Calabria now houses them.

5. Discobolus (Discus Thrower)

The artist Myron sculpted this bronze figure in the 5th century BCE. Although the original is now lost, it is recognized through several Roman copies. The copies include the Lancellotti Discobolus and the Townley Discobolus (seen in the painting above). The sculptor has taken the opportunity to showcase the dynamic pose and prowess of the athlete as he prepares to throw a discus.

6. Laocoön and His Sons

Artists created this Roman copy of a Greek Hellenistic sculpture from the 1st century BCE to represent the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons being attacked by sea serpents. Laocoön captures intense emotion, dramatic movement, and extreme details, highlighting the mastery of ancient Greek sculpture.

7. Venus de Milo

Also known as the Aphrodite of Milos, this iconic marble sculpture represents the goddess of love and beauty. Despite its missing arms, viewers continue to celebrate the statue for its graceful form, flowing drapery, and idealized depiction of female beauty. Venus de Milo has influenced how artists depict the female body for centuries. On display in the Louvre.

8. Apollo Belvedere

This Roman marble copy is an interesting example of Romans copying the Greek Hellenistic style. The statue’s dynamic pose, idealized physique, and confident expression exemplify the harmonious balance between strength and grace. Renaissance artists highly regarded the work, and it influenced many who followed.

9. Dying Gaul (or “The Dying Galatian”)

This is a Roman marble copy of a Greek original sculpture, dating back to approximately 320 BCE. The work depicts a wounded Gallic warrior in his final moments, marked by clear signs of injury and suffering. Viewers recognize the sculpture for its poignant depiction of the warrior’s pain, vulnerability, and bravery. The Capitoline Museums in Rome house the marble statue.