What makes for a happy life? Do we seek pleasure and enjoyment, or do we develop resilience and embrace self-discipline? Hedonism and Stoicism offer two extremely divergent answers to this ancient question. Hedonism holds that the key to happiness lies in pleasure, whether through luxury, activities, or everyday pleasures. Stoicism believes happiness comes from within through virtue, self-control, and emotional balance. Below, we’ll delve into their essential concepts, strengths, and relevance today, and consider whether a balance between the two might be the way forward.

The Hedonist’s Pursuit: Happiness Through Pleasure

Hedonism centers around pleasure. It suggests we can lead happy lives by maximizing enjoyment and minimizing pain.

The view goes back to Aristippus of Cyrene, a student of Socrates, who thought the best way to live was to indulge yourself whenever it felt good, an idea known as Cyrenaic Hedonism because he lived in (and possibly founded) a community of these thinkers in Cyrene.

However, not all hedonists have agreed that we should seek out every possible pleasure without worrying about the consequences.

Epicurus believed something quite different. He argued that the truest form of happiness would involve having a lot of pleasant experiences and other things, such as friends and philosophical conversations.

Epicurean Hedonism is the belief that long-term contentment comes from friends, moderation, and inner peace. For Epicurus, lasting happiness could be found in a glass of water and good conversation rather than a feast.

Self-care, social media envy, and FOMO all feed modern hedonism’s rise. Traveling the world and spending on luxury items and experiences (from skydiving to sushi pop-ups) is how many people now try to lead a happy life.

The slow food movement, positive psychology, and a revived interest in Stoic philosophy taught us to accept what we cannot change: aspects of these popular trends would not look alien to the ancient Greeks.

But is it possible to live meaningfully only through enjoying yourself? Yes, say some contemporary hedonists, as long as you do it wisely.

The Stoic’s Path: Happiness Through Virtue

Happiness is viewed in a different way by Stoicism. Rather than telling people to chase feelings of pleasure, this ancient Greek philosophy teaches that being truly fulfilled comes from having inner goodness, self-control, and wisdom.

According to Stoicism, which was founded by Zeno of Citium, because things like success or failure, wealth or poverty happen by fate (and not our own doing), we shouldn’t rely on them for happiness. Instead, he said we should care more about having a strong character because then we’ll feel at peace, now and forever.

Stoics believe people can’t always get what they want or avoid stuff they don’t. Everything from pain to poverty or misfortune is simply part of life’s rich tapestry (as is luck and health).

Key values of Stoicism include accepting things that cannot be changed, thinking rationally about matters, and not being too upset by whether you win prizes.

Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius followed these principles to stay calm under pressure. Likewise, Epictetus, once a slave and later a free man who took up philosophy, reckoned misfortune stems largely from our opinion about events rather than the happenings themselves.

Today, people like Stoicism because it helps them deal with stress, failure, and unpredictability. Stuff you don’t want on social media, keeping a cool head in trouble, deciding to work on yourself instead of getting rich—there are loads of examples showing how these ideas can bring happiness in practice.

But hang on! Is it really a good idea to give up pleasure? Yes, say the Stoics. However, if you ask a hedonist, they may disagree.

The Role of Desire: Indulgence vs. Control

An essential disagreement between Hedonism and Stoicism is rooted in the issue of desire. Hedonists believe people ought to accept desires—whether for good food, comfort, or new thrills—since they make life enjoyable. For Stoics, however, such desires are either irrelevant or destructive.

For Hedonists, pleasure has an important place in one’s life: it can make life better overall. Epicurus thought there was nothing wrong with having desires so long as one went about fulfilling them sensibly.

Real happiness can come from things like having a good meal with friends, enjoying a warm bath, or talking to somebody you love in-depth. But you need to be moderate and not overindulge—too much food, drink, etc.

There is another type of Hedonism called Cyrenaic. Followers believe we should aim to have as much pleasure as possible, even if it is short-lived.

Stoics such as Epictetus and Seneca cautioned about the perils of desire: wanting things ties you emotionally to them—a recipe for misery. If you hanker after power, wealth, or recognition, then those wishes must command your life. It’s far better not to want them in the first place.

Hedonism today closely tracks this line of thought—and yet so does its opposite, minimalism. Both encourage certain ways of living (and buying).

But do any of these approaches actually make people happier than they would otherwise be? It’s an age-old question: can we ever be satisfied with what we have, or must we always want more?

Might there be a middle path between these two apparently competing ideologies after all—one that advocates balance as key to human flourishing?

Dealing With Pain: Escape or Endurance?

Pain is inevitable, but our attitude towards it is not. Those who follow a hedonistic philosophy seek to avoid suffering at all costs, whereas Stoics think enduring hardship is key.

When you’re a hedonist, reducing or preventing agony is a top priority. To Epicurus, one way was getting rid of unnecessary agony by surrounding yourself with pals and living an untroubled life full of simple pleasures—or none at all.

Things have moved on since then. Nowadays, lots of people don’t want to deal with pain, so they watch TV, go online, take drugs for fun… Why feel awful when there are so many ways to feel good?

In contrast, Stoics consider pain to be instructive. Epictetus, who had been enslaved before gaining his freedom, believed that suffering can fortify us—but only if we acknowledge that some things lie beyond our control.

Marcus Aurelius was also a Stoic; when he wasn’t ruling an empire, he was battling enemies abroad or disease at home. Yet somehow, he remained perfectly calm. Stoicism doesn’t mean seeking out pain just for the sake of it, but accepting that pain is part of life, and that we can learn from it instead of just trying to forget about it.

These days, the same kind of argument is being used in psychology. On one side, there are therapists who think they can help us avoid problems such as depression and anxiety (which can make life really painful) by encouraging self-care routines that include plenty of rest and relaxation—a philosophy known as hedonism.

Is pain dulled by pleasure, or do we accept it and enjoy life’s journey? Perhaps both are true, depending on the challenges encountered.

Social Life: Engaging vs. Detaching

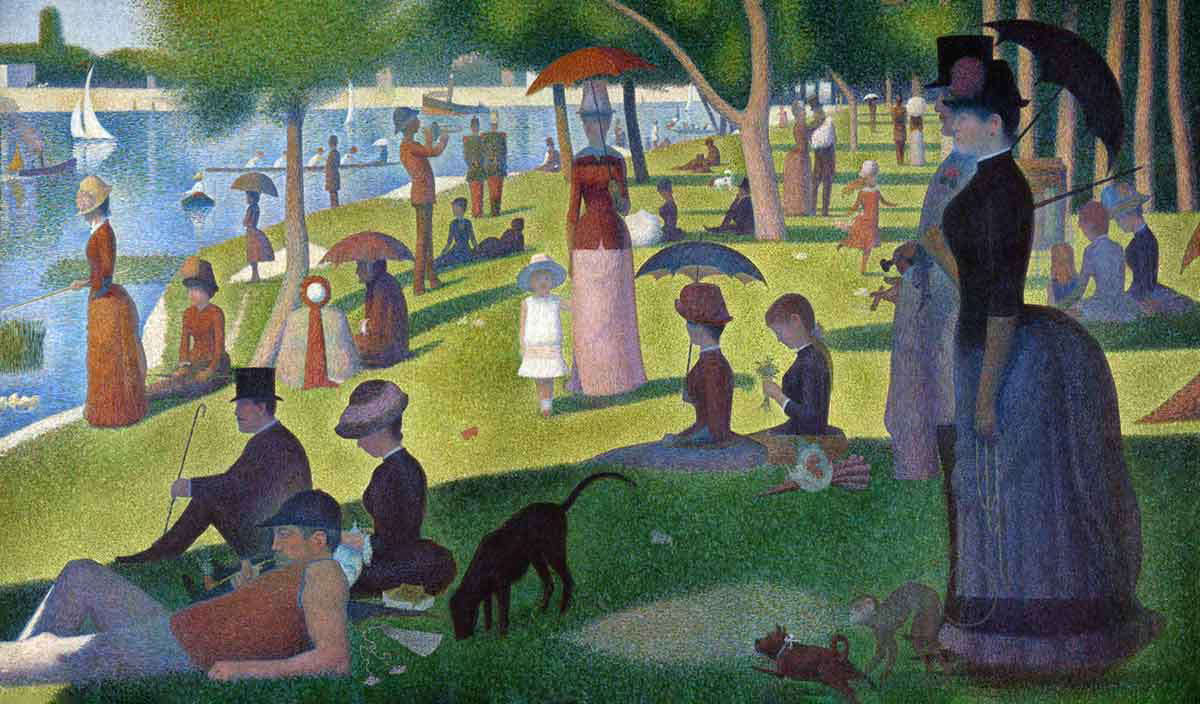

Hedonists and Stoics disagree on what makes a good life, whether you need other people for happiness. The Hedonist tradition says that relationships, fun activities, and feeling like part of a group are really important if we want to feel good about our lives.

Stoicism teaches the opposite view that we should learn to stand alone emotionally and not rely on receiving praise or support from others.

To an Ancient Greek thinker like Epicurus, being alive meant being with friends: their company gave him huge pleasure (as well as a lot of other things). He thought having friends around to laugh with, talk to, and hang out with was one key to contentment.

So, anyone who wants to follow in his footsteps today might well turn to social networking sites such as Facebook or Instagram for tips on how best to make this happen. You could sum up his position this way: “Shared joy is double joy.”

Stoics, conversely, offer another mindset. They instruct people not to seek happiness from external sources—it is within. Seneca noted that trying to please people and seeking status is a gateway to unhappiness.

Instead, Stoics promote introspection, working hard at your profession or studies, and intimate but selective friendships.

One could liken this to some popular lifestyle trends today: minimizing social media and screen time, simplifying life to make room and time (“digital detox”), or focusing completely on one activity at a time (deep work).

Today, we see this debate in two lives: with hundreds of online contacts like Facebook, Snapchat, and Twitter, or in isolation with your own mind. Do you like numerous different connections with others, and does it make you happy? Or do you like to step back from online life, and does that give you peace?

Which Path Leads to True Happiness?

While both Hedonism and Stoicism have their merits, they are not without their flaws.

The pursuit of pleasure, excitement, and social connection can lead to an overindulgent, dependent, and therefore ultimately unsatisfying life—yet the alternative (a “good” life in the original sense), founded entirely upon self-control, might seem too austere or cold.

Is there a way to be truly happy (as well as resilient), rather than cherry-picking bits from each of the “big two” ancient schools?

One possible solution comes from a balance: learning how you need both sides. So don’t follow pleasure blindly. Sometimes, deny yourself short-term treats for long-term joy (like Epicurus with his simple food). And when things don’t go your way, do what Marcus Aurelius did—and ask if they’re really bad, as well as adjusting your desires.

Consider a person who is dedicated to their job but also enjoys good food and holidays. Or someone who meditates every day, leads a disciplined life, values close friendships, and loves to have fun.

Happiness isn’t about choosing between these types of people—it’s finding ways to be both at once. Can we savor life’s daily pleasures yet not let them rule us? Stand up well in a crisis and still feel happy?

Maybe the answer is not to follow one path with its rules for living, but to take ideas from each that suit us. At any rate, we might end up feeling content if we can combine Stoic self-control with Hedonistic enjoyment—and realize it!