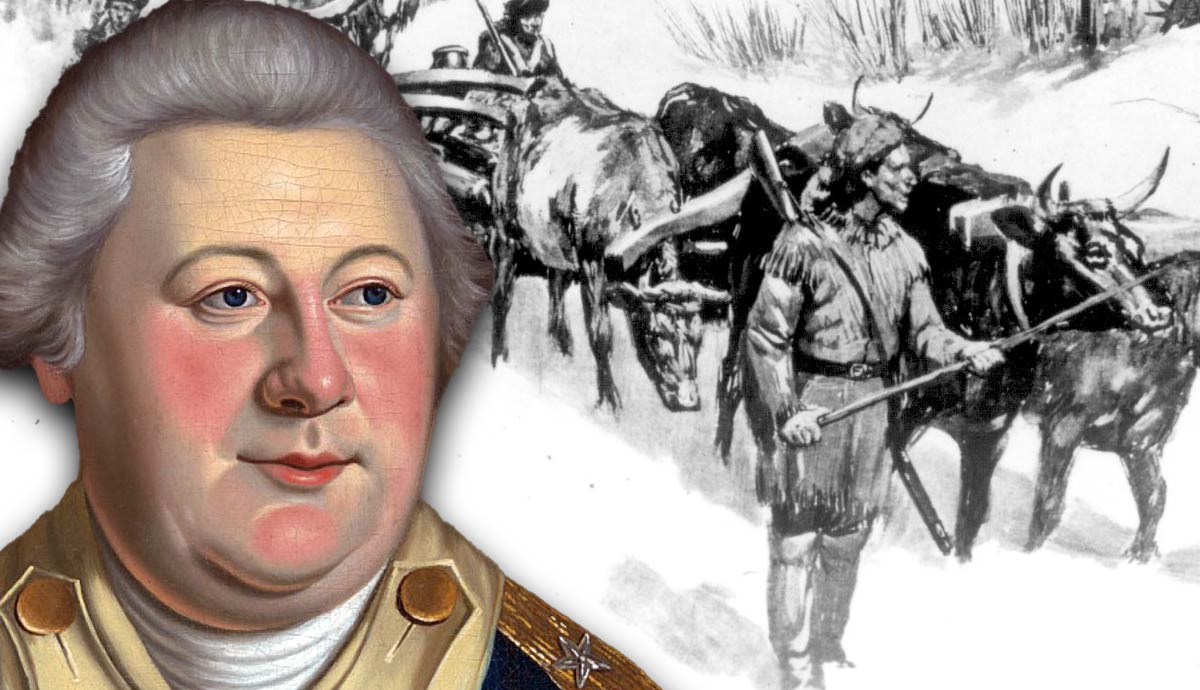

From Benjamin Franklin to George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, dozens of individuals played an important role in leading the United States in its struggle for independence from British rule, but few individuals influenced the course of the American fight for independence more than Henry Knox, the father of modern United States artillery. While the desire for freedom, bold strategic decisions, and international allies aided the colonies in protracted war, ultimate triumph in the American Revolutionary War could not have been accomplished without General Knox’s men and guns.

Early Life

Born in Boston in 1750, Henry Knox grew up supporting colonial causes for independence. As one of ten children of two immigrants from Northern Ireland, Knox and his family were eager to call the American colonies their home. The future Continental Army general dropped out of school following his father’s death, soon rising from apprentice to owner of a local bookshop called the London Book Store. There, Knox valued hard work, education, freedom of ideas, and privately studied the history and theory of warfare by reading books he ordered for British officers in the city. One of his customers, John Adams, shared Knox’s ideals and would go on to become a fellow Founding Father and the second president of the United States.

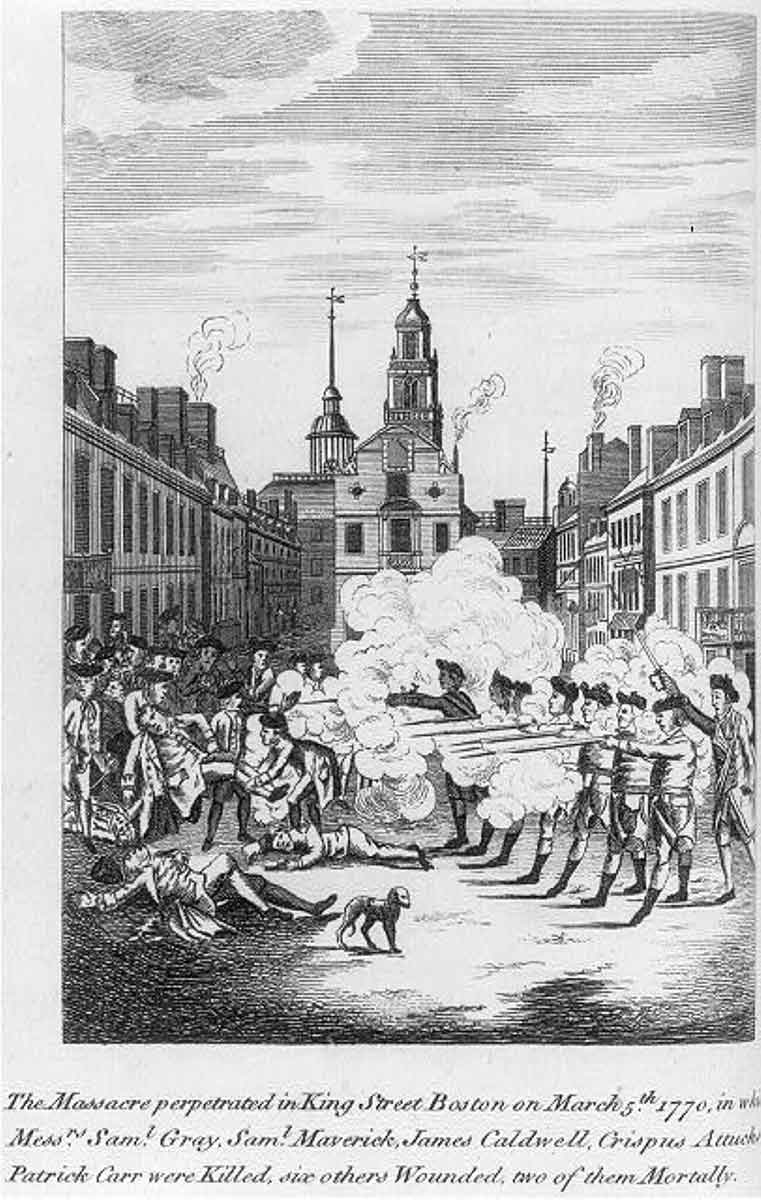

As a Boston native and resident, Knox experienced oppressive British laws that caused tensions between the North American colonies and the British government in London. Fueled by perceived injustices surrounding the Stamp and Townshend Acts, tensions boiled over into violence in Boston during Knox’s formative years, resulting in the Boston Massacre of March 5, 1770. The street skirmish between American colonists and British soldiers, which Knox witnessed first-hand and testified at the subsequent trials, rapidly escalated into the slaughter of Knox’s fellow citizens. The Boston Massacre emboldened anti-British rhetoric and encouraged colonists to support causes for freedom including the Boston Tea Party.

Military Career and Personal Life

As a member of the patriotic organization Sons of Liberty, Knox joined a local artillery company at just 18 years old. At approximately six feet tall and 250 pounds, Knox’s prominent stature was one that demanded respect in colonial militias. Two years into his military career, Knox was appointed as second-in-command of the Boston Grenadier Corps where he developed expertise in the art and science of using artillery. While learning the ins and outs of ballistics on a hunting trip, he lost two fingers on his left hand from an unexpected explosion.

A year before the American Revolutionary War began, Knox married Lucy Flucker, the daughter of a high-ranking British official in Massachusetts. Lucy defied her loyalist family to marry Knox, and during the war the couple regularly exchanged letters. Most notably, she advocated for equality in marriage, warning her husband that he should not consider himself the commander-in-chief of the household after the end of the war. The couple had 13 children together, however, ten of them died during their youth, adding personal loss to wartime struggles.

Despite growing business successes and his beloved young wife, 1775 represented a significant turning point in the young patriot’s career. As the first shots of the conflict were fired at Lexington and Concord near Boston in April 1775, Knox was forced to close the London Book Store, and the couple fled Boston.

The Outbreak of War

After leaving Boston, Knox quickly volunteered for service under General Artemas Ward, leveraging his engineering expertise to design defensive fortifications for the Patriots. At the Battle of Bunker Hill, the first significant action after Lexington and Concord, Knox commanded the Patriot artillery. Although the American rebels were obliged to withdraw from their positions, Knox’s guns inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy.

As early battles progressed, John Adams advocated for Knox to receive an official officer’s commission through the Continental Congress, a designation Knox lacked despite his military experience. In November 1775, George Washington granted Knox a commission as colonel of the Continental Army’s artillery regiment, with which he would change the course of the war.

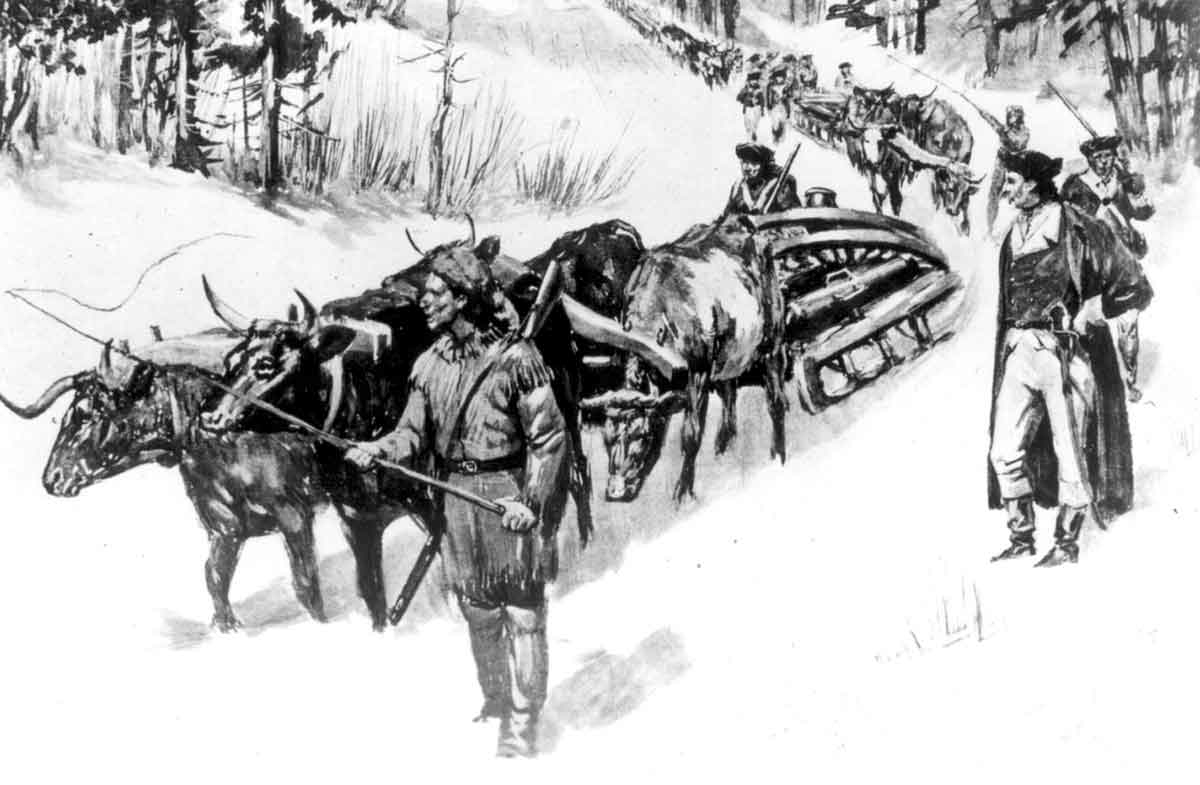

Although he was now commander of the American artillery, Knox had few guns to hand in the Siege of Boston. To remedy this shortcoming, Knox asked Washington for permission to transfer 60 tons of artillery pieces to Boston from Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York in January 1776. With Knox’s guns at his disposal, Washington forced the British to evacuate from Boston in March.

After building up coastal artillery defenses along Connecticut and Rhode Island, Knox headed south towards New York City, where he befriended Alexander Hamilton, the local artillery commander who would soon become Washington’s right-hand man. Knox’s artillery saw plenty of action at the Battle of Long Island in September 1776 as part of Washington’s 20,000-strong force, but the Continentals were defeated and forced to withdraw into New Jersey. Despite the setback, the American officers had the opportunity to regroup during the winter and formulate a plan that would turn the tide of the war.

Seizing the Initiative

After a series of defeats and with limited supplies, Washington understood that a bold plan was needed to shift the momentum of the war. The commander-in-chief met with his subordinate commanders, including Knox, and the group decided to cross the Delaware River on Christmas night to attack a Hessian outpost at Trenton. As the commander of Continental artillery, Knox attached three to four cannons at the front of each advancing column, and the regular ferry transported the assets across the icy waterway. Washington left with the first boat across the Delaware River, leaving Knox in charge of loading the remaining troops.

As the Continental Army launched its attack, Knox positioned his artillery to target the main intersection at the outpost’s north end. The commanding position of Knox’s guns convinced the garrison’s commander, Colonel Rall, to surrender alongside his 900 men. One day after the Battle of Trenton, Knox was recognized for his bravery and expertise via promotion to brigadier general and expansion of his command to a corps of five regiments.

After commanding artillery during the American victories at the Second Battle of Trenton and the Battle of Princeton, Knox removed himself from the battlefield to supervise efforts to manufacture guns and recruit artillerymen. Despite not returning to the front lines until mid-1777, Knox’s influence in turning the tide of the war is undeniable, and the general continued to have an impact over the course of the war.

Defying Replacement

Upon his return to Washington’s side, Knox learned that the Continental Congress appointed a French officer, Philippe Charles Tronson du Coudray, as the commander of American artillery. While French military expertise would be crucial to winning the war, Knox was certainly displeased with this decision. He quickly lobbied Congress to reappoint him to the post with support from senior officers including John Sullivan and Nathanael Greene. Even General Washington wrote a letter on Knox’s behalf. Congress responded by reinstating Knox to his rightful command, leaving du Coudray as Inspector General of Ordnance.

After major British victories at the 1777 Battles of Brandywine and Germantown, Knox bunkered down for a harsh winter at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. As the Americans struggled with lack of ammunition, warm clothing, and supplies, Knox stood by Washington despite fellow officers who called for the future president’s replacement. When the cold weather finally gave way, Knox’s resilience paid off. Continental artillery soon enabled the Patriot victory at the 1778 Battle of Monmouth, where wisely emplaced gun crews targeting the British flanks forced the Redcoats to retreat.

End of the War

Knox and his artillery played a significant role in forcing the final British surrender at the Siege of Yorktown. Washington, Knox, and their French allies trapped General Charles Cornwallis in the narrow Yorktown peninsula, and American artillery bombarded the British defenses for three weeks. During the battle, artillery proved especially effective in overcoming the enemy trench networks that infantrymen could not attack without risking significant casualties. At the height of the battle, American artillerymen fired 1,500 projectiles per day at the British.

Due to French naval support, inclement weather, and relentless cannon fire, the British had no choice but to surrender. The three parties negotiated the terms in the Articles of Capitulation on August 19, 1781, marking an end to major hostilities. Knox was promoted to major general following the victory at Yorktown, setting the stage for further influence in his postwar activities.

Legacy

Knox’s remarkable legacy extends beyond that of just an artillery commander during the American Revolutionary War. Following the fight for independence, Knox supervised the removal of the British military from New York City. Two years later, the Confederation Congress appointed Knox as the United States’ first Secretary of War. Knox supported the adoption of the United States Constitution and retained his office as Secretary of War in Washington’s cabinet until December 1794.

One of Knox’s most significant long-term accomplishments was to set up a military school in New Jersey in 1779 to train artillerymen. The school acted as the precursor of the modern United States Military Academy at West Point, which has trained some of the military’s most influential officers in history. Despite his prominence as a larger-than-life figure, Knox’s death was particularly anticlimactic. In 1806, the father of American artillery passed away at his home in Thomaston, Maine, after ingesting a chicken bone that ruptured his arteries.

From the very beginning of the war as a militia officer to the conflict’s final day as Washington’s most senior lieutenant, Knox was involved in the American Revolutionary War every step of the way. With his skillful deployment of limited resources and his unqualified support for General Washington, Henry Knox and his men made a decisive contribution to America’s successful armed struggle for independence.