The enigmatic figure of Hermes Trismegistus, revered in ancient Egypt and Greece as the embodiment of wisdom, would become the establishing figure in a philosophical tradition known as Hermeticism, which would profoundly influence Western thought for millennia. Through texts like the Emerald Tablet, which contains the famous axiom “as above, so below,” Hermetic teachings proposed a universe of correspondence between the microcosm and the macrocosm, where mind and matter intertwine in divine harmony. Although often operating in the shadows of intellectual history, this esoteric current has persistently shaped how seekers understand the relationship between consciousness, nature, and the cosmos throughout the centuries.

Who Was Hermes Trismegistus?

The exact origins of Hermes Trismegistus, like much of his teachings, are shrouded in mystery and ongoing debate. His name and identity represent a syncretism between the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.

While Hermes was the messenger of the Greek gods, delivering information to both divine and mortal beings, Thoth was the Egyptian god of wisdom and knowledge. He was venerated since at least 3000 BCE and credited with the invention of hieroglyphics, astronomy, architecture, geometry, and other related areas of ancient study.

As such, the fusion of the two gods, as represented by the sage Hermes Trismegistus, symbolized the imparting or transmission of secret, ancient knowledge. Since both deities shared associations with writing, magic, and mediation between the divine and human realms. The content of Hermes Trismegistus’s teachings was thought to be divinely inspired.

This brings up the question of whether Hermes Trismegistus was a god himself. The answer varies depending on tradition. Some accounts portrayed him as a god incarnate who chose to share celestial knowledge with humanity, while others described him as a divinely inspired human sage who achieved spiritual transcendence through his extraordinary wisdom.

Thoth and Ammit in the Book of the Dead, Ani’s Judgment, 1250 BCE (19th Dynasty). Source: British Museum, London

The epithet “Trismegistus,” meaning “Thrice-Greatest,” has likewise inspired varying interpretations. Some suggest it refers to his mastery of the three parts of ancient universal wisdom: alchemy, astrology, and theurgy. Others propose it signifies his triple role as philosopher, priest, and king, or his supreme excellence in thought, speech, and action.

In terms of iconography, representations of Hermes Trismegistus evolved over centuries. Early depictions often depicted him with attributes of Thoth, featuring an ibis head or a baboon companion, while later Greco-Roman imagery portrayed him as a bearded sage holding the caduceus, a staff entwined with serpents that symbolized healing and transformation.

What Is the Hermetica?

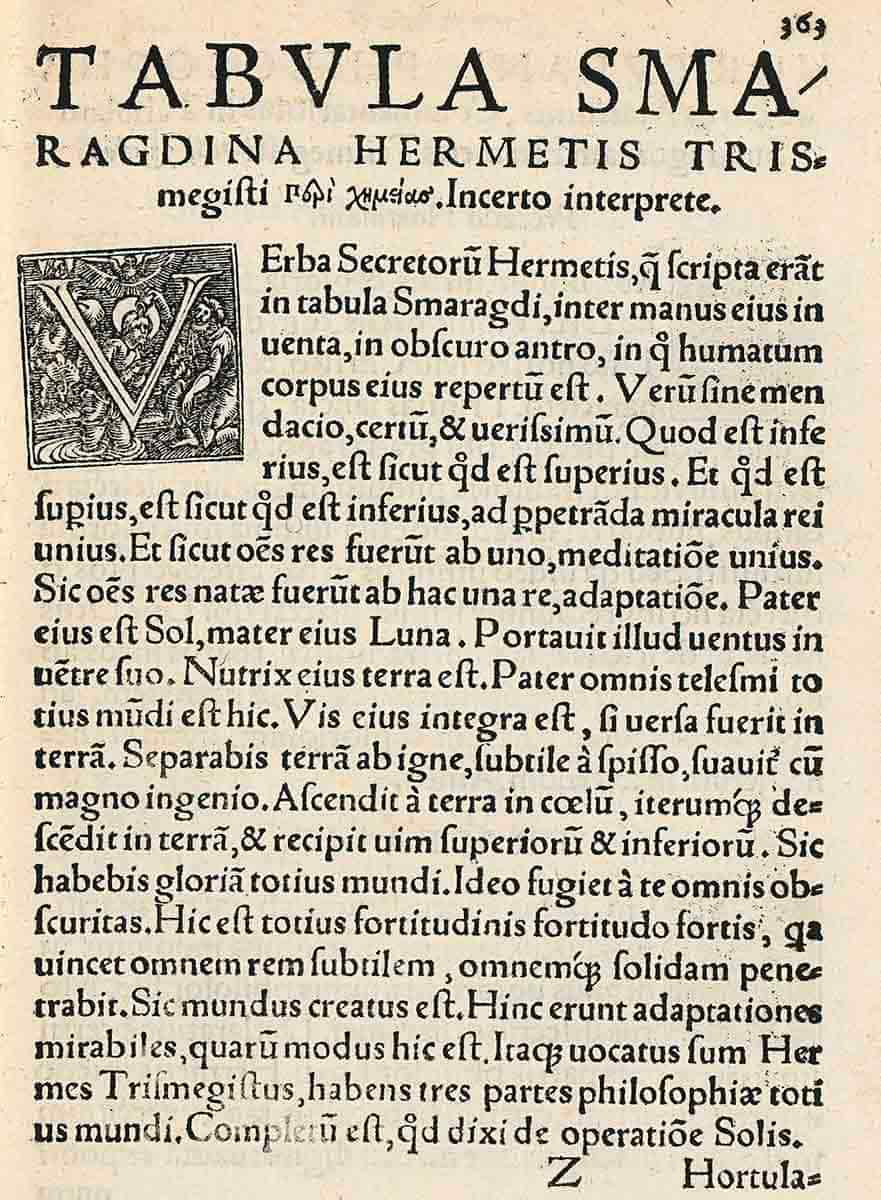

The Hermetica is a diverse collection of writings and teachings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus. At its core lies the Corpus Hermeticum, which is a compilation of 17 philosophical treatises written between approximately 100 and 300 CE, although they are often credited with deriving from much earlier prophetic insights.

These texts explore profound metaphysical concepts through dialogues and revelations, often featuring Hermes instructing disciples in divine wisdom. Although many of these texts are supposedly dated back to the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, they were not collected together and compiled by the Byzantine philosopher Michael Psellus until the 11th century.

The Corpus presents a sophisticated philosophical system that blends Platonic ideas with Egyptian religious elements and Greek mysticism, addressing fundamental questions about divinity, cosmology, and humanity’s spiritual potential to transcend its typically mundane dimensions.

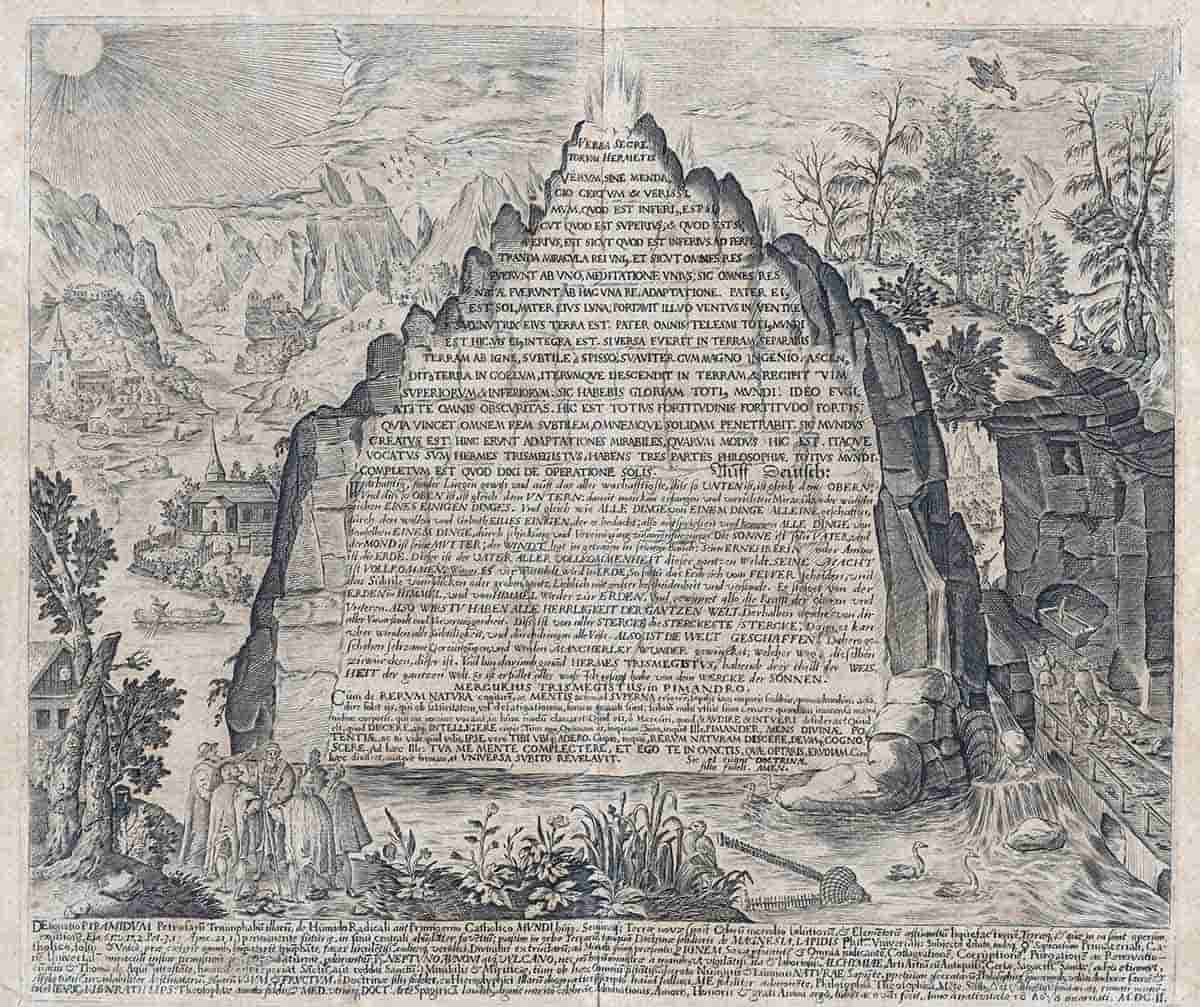

Perhaps the most famous text within the Hermetica is the enigmatic Emerald Tablet. This concise yet profound text crystallizes Hermetic wisdom into a series of cryptic statements that supposedly encapsulate the key tenets of Hermes Trismegistus’s teachings.

Its most famous axiom, “That which is above is from that which is below, and that which is below is from that which is above,” commonly paraphrased as “As above, so below,” encapsulates the Hermetic principle of correspondence between opposing and varying elements of the world. The principle also suggests that patterns and processes occurring in one realm of existence are mirrored throughout all levels of reality, establishing an ever-present and interconnected cosmic framework.

Alongside these deeply spiritual components of the Hermetica, there were also many practical texts on alchemy, astrology, and magical techniques. While the philosophical texts explore spiritual transformation and cosmic understanding, the technical writings provide instructions for manipulating natural forces through occult knowledge.

Islamic Preservation of Hermeticism

The earliest esoteric communities venerating Hermes Trismegistus emerged in Hellenistic Egypt, where his teachings spread through intimate circles of dedicated initiates. These seekers gathered regularly to study sacred wisdom and engage in contemplative practices, all with the aim of achieving spiritual transformation and divine understanding.

Through their devoted efforts, these early practitioners carefully preserved these teachings in sacred texts that would eventually form the foundation of what we now know as the Corpus Hermeticum. As classical civilization gave way to the Medieval period, the preservation of this precious Hermetic knowledge might have been lost to Western civilization were it not for the diligent work of Arabic scholars and translators.

These Islamic intellectuals recognized the profound value in Hermetic wisdom, incorporating it into their developing alchemical and astrological traditions. Their reverence for this knowledge was further strengthened by the widespread belief that Hermes himself was the prophet Idris mentioned in the Quran. This connection elevated the status of his teachings and encouraged their flourishing throughout the great centers of learning across the Islamic world.

The careful Arabic translations and insightful commentaries on Hermetic texts served as crucial links in an unbroken chain of transmission over centuries. This preservation effort ensured that this ancient wisdom would not disappear but instead find its way back to Europe through vibrant cultural exchanges.

Particularly in multicultural hubs like Byzantium, Moorish Spain, and Sicily, scholars from diverse traditions began to interact more frequently, share knowledge, and collaborate, allowing Hermetic wisdom to once again take root in Western intellectual soil and eventually flourish during the Renaissance period.

Hermeticism & the Renaissance

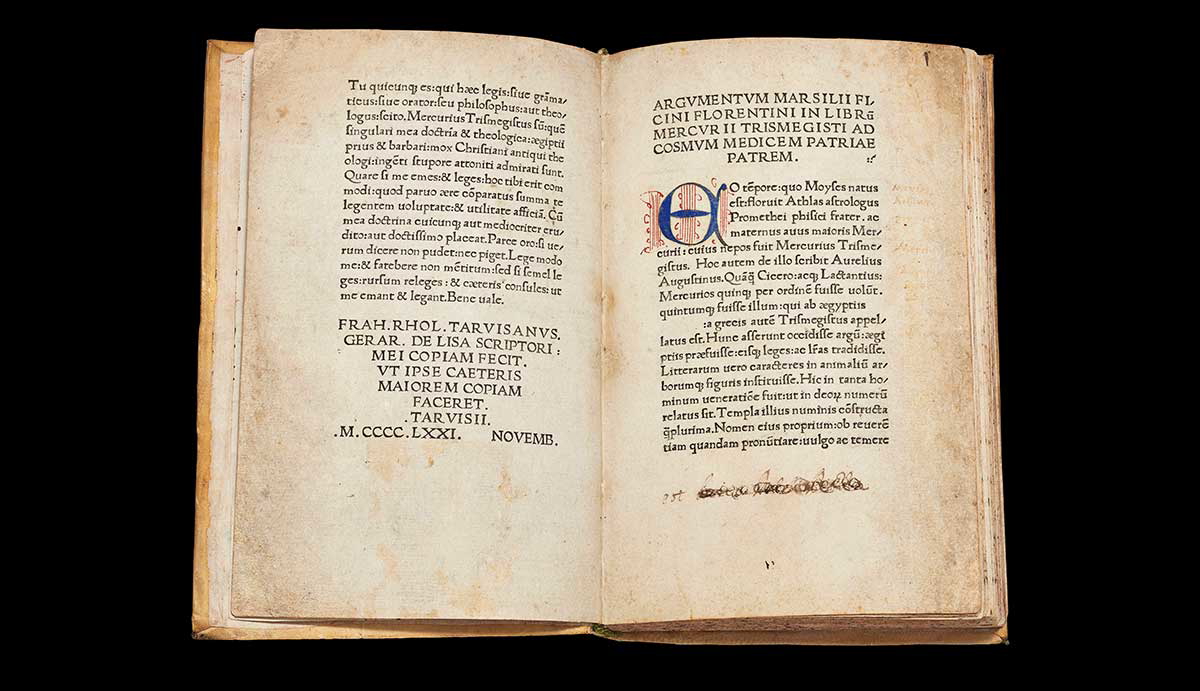

This cultural exchange and rediscovery of ancient wisdom largely defined the Renaissance, ushering in a dramatic revival of Hermeticism that would transform European intellectual life. The pivotal moment came in 1463 when Marsilio Ficino, working under the patronage of Cosimo de’ Medici, completed his Latin translation of the Corpus Hermeticum from Greek manuscripts that had been meticulously compiled by the Byzantine scholar Michael Psellos.

Ficino’s translation arrived at a perfect historical juncture, when Renaissance thinkers were actively seeking alternatives to the long-established dominance of church philosophy and thought. This sparked an explosion of interest in Hermetic philosophy that would flourish throughout the 15th and 16th centuries.

As Hermetic ideas permeated European intellectual circles, the subsequent centuries witnessed the natural evolution of this influence through the formation of numerous secret societies and fraternal orders claiming Hermetic lineage.

Organizations such as the Rosicrucians and certain branches of Freemasonry embraced this ancient wisdom, developing elaborate initiatory systems and rituals based on Hermetic principles of spiritual transformation and the quest for hidden knowledge.

This underground current of Hermetic thought later resurfaced with renewed vigor during the 19th century, flowing naturally into the Romantic movement’s spiritual sensibilities and fueling a significant occult revival.

This renaissance of esoteric interest manifested through influential organizations like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the Theosophical Society, which creatively synthesized traditional Hermeticism with other esoteric currents to create magical systems and spiritual practices tailored for modern practitioners.

During this fertile period of occult innovation, visionary figures such as Eliphas Lévi, Aleister Crowley, and Dion Fortune built upon this foundation, developing sophisticated magical systems rooted in Hermetic principles while thoughtfully adapting this ancient wisdom to address the unique spiritual needs and intellectual concerns of an increasingly industrialized and scientific age.

What Are the Core Principles of Hermeticism?

Throughout its development, Hermeticism has maintained a strong emphasis on initiatory experiences and altered states of consciousness, with practitioners employing meditation, visualization, ritual, and occasionally psychoactive substances to achieve direct spiritual insight and communion with divine forces.

The Hermetic path has consistently emphasized the transformation of consciousness as the key to understanding reality. It suggests that certain truths can only be fully grasped through personal experience rather than intellectual study alone.

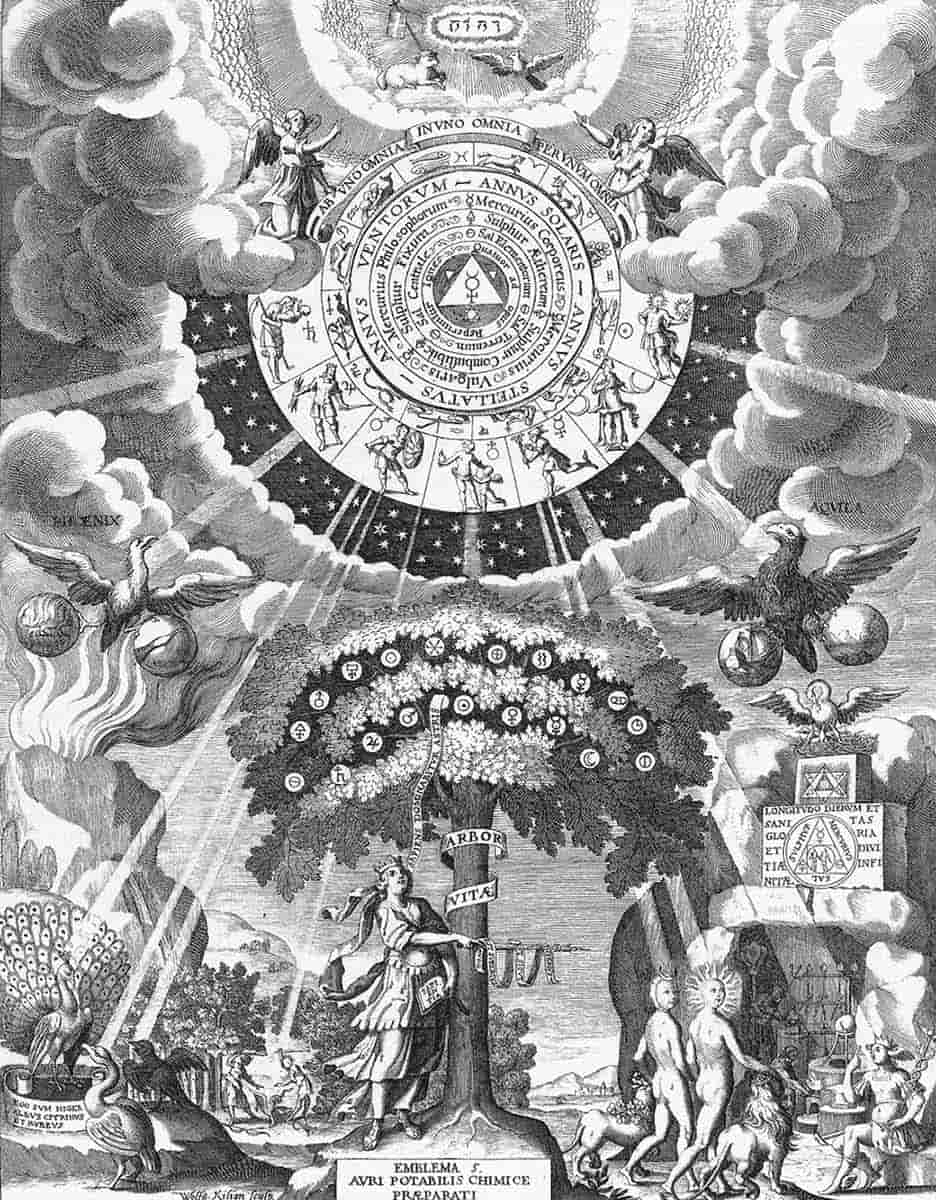

Also central to Hermetic philosophy is the principle of correspondence. This concept suggests a fundamental symmetry between macrocosm and microcosm: the universe at large and the individual human being. Hermeticists believe that patterns existing in celestial realms are mirrored in terrestrial ones, creating a web of meaningful connections throughout all levels of existence.

Another foundational concept in Hermeticism is the divine nature of the human mind. The Corpus Hermeticum teaches that humans possess a spark of the divine intellect, enabling them to comprehend cosmic mysteries and potentially achieve “gnosis,” or direct knowledge of the divine. This perspective positions humans as potential co-creators with the divine, capable of participating in the ongoing creation and transformation of reality through focused will and imagination.

Complementing these principles is the Hermetic understanding of polarity and rhythm. Hermeticists recognize that all phenomena contain their opposites and exist in dynamic tension: light and darkness, creation and destruction, masculine and feminine energies. Rather than viewing these as absolute dualities, the tradition teaches that apparent opposites are actually complementary aspects of a greater unity.

The practical application of Hermetic principles culminates in the concept of transmutation, which is the ability to change one state of being into another through conscious intention and ritual action. While popularly associated with alchemical attempts to transform base metals into gold, this principle extends far beyond material concerns.

Hermetic transmutation ultimately aims to refine the practitioner’s own consciousness, transforming the “lead” of ordinary awareness into the “gold” of spiritual illumination.

How Hermeticism Influenced Prominent Thinkers

Hermeticism’s profound impact on intellectual history spans centuries, shaping the minds of philosophers, scientists, artists, and psychologists alike. Contrary to the popular belief that positions Hermeticism as exclusively “occult,” early modern science was also deeply intertwined with Hermetic principles.

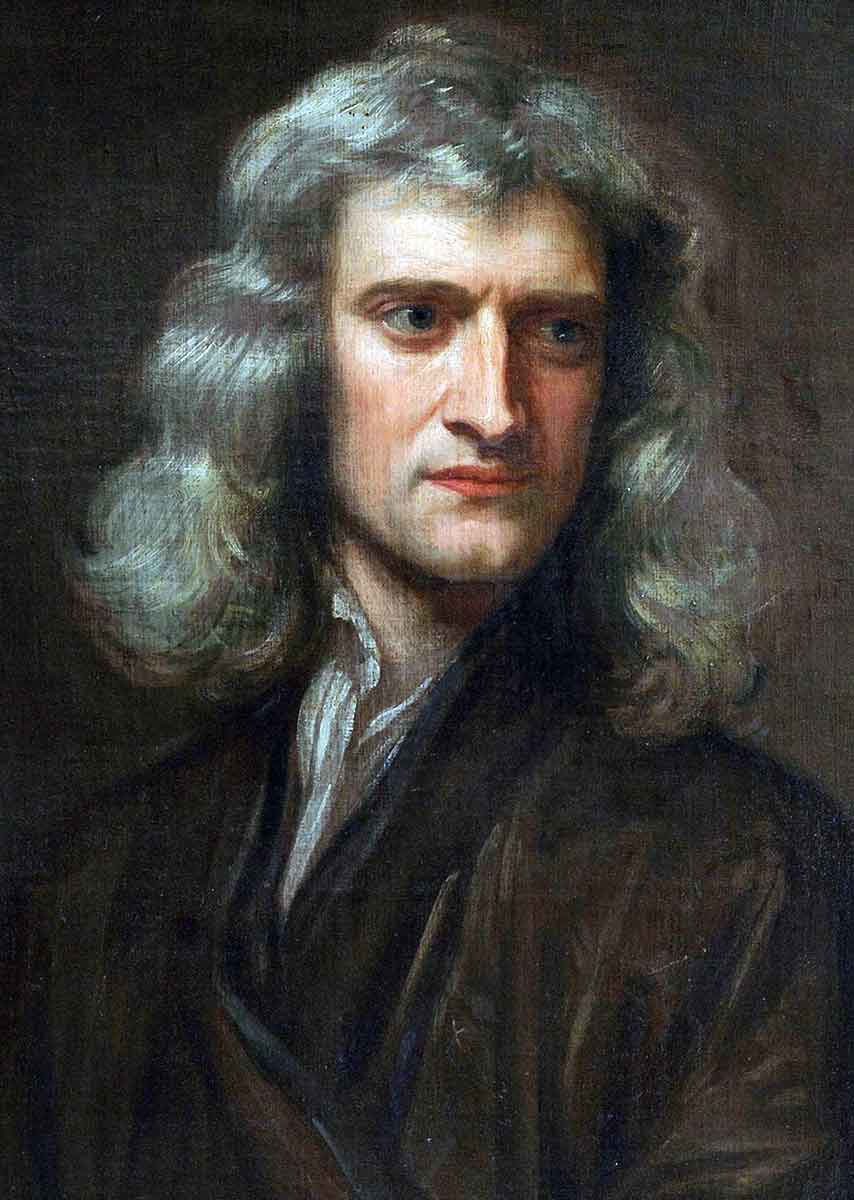

Paracelsus, a revolutionary figure in medicine, was vocal about applying the Hermetic maxim “as above, so below,” and developed treatments based on correspondences between celestial bodies and human organs. Even Isaac Newton, while pioneering physics and mathematics, devoted significant time to alchemical experiments. His private papers reveal extensive studies of Hermetic texts, often guarding the ways in which Hermeticism was applied in his work.

The influence of Hermeticism was not limited to scientific inquiry; it also flourished in creative expression. Hermetic symbolism permeated Renaissance art and architecture, with artists embedding esoteric imagery in their works.

Later literary figures continued this tradition. William Blake‘s mystical poetry reflected Hermetic concepts of divine imagination, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe‘s Faust explored alchemical transformation. W.B. Yeats also incorporated Hermetic symbolism throughout his poetry, even joining the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

This esoteric current eventually flowed into modern psychological thought, particularly through the work of Carl Jung. Jung recognized the psychological significance of Hermeticism, viewing alchemical processes as metaphors for individuation, the journey toward psychological wholeness.

Jung collected alchemical texts and analysed their symbolism, finding that Hermetic concepts of transformation mirrored the integration of conscious and unconscious elements in the psyche. Throughout history, these thinkers engaged with Hermeticism not merely intellectually but practically, conducting alchemical experiments, creating talismans, and performing rituals designed to harness cosmic energies.

The Modern Legacy of Hermeticism

In recent decades, academic scholars have significantly reframed our understanding of Hermeticism’s historical significance, revealing its profound impact on Renaissance thought and the early development of modern science, thereby challenging previous dismissals of its esoteric traditions as mere superstition.

Yet it remains an intriguing feature of Hermeticism that its influence on intellectual thought is often intentionally obscured, even by its advocates. This is the continuation of a tradition that stems from historical necessity to protect esoteric knowledge during periods of religious persecution and scientific skepticism.

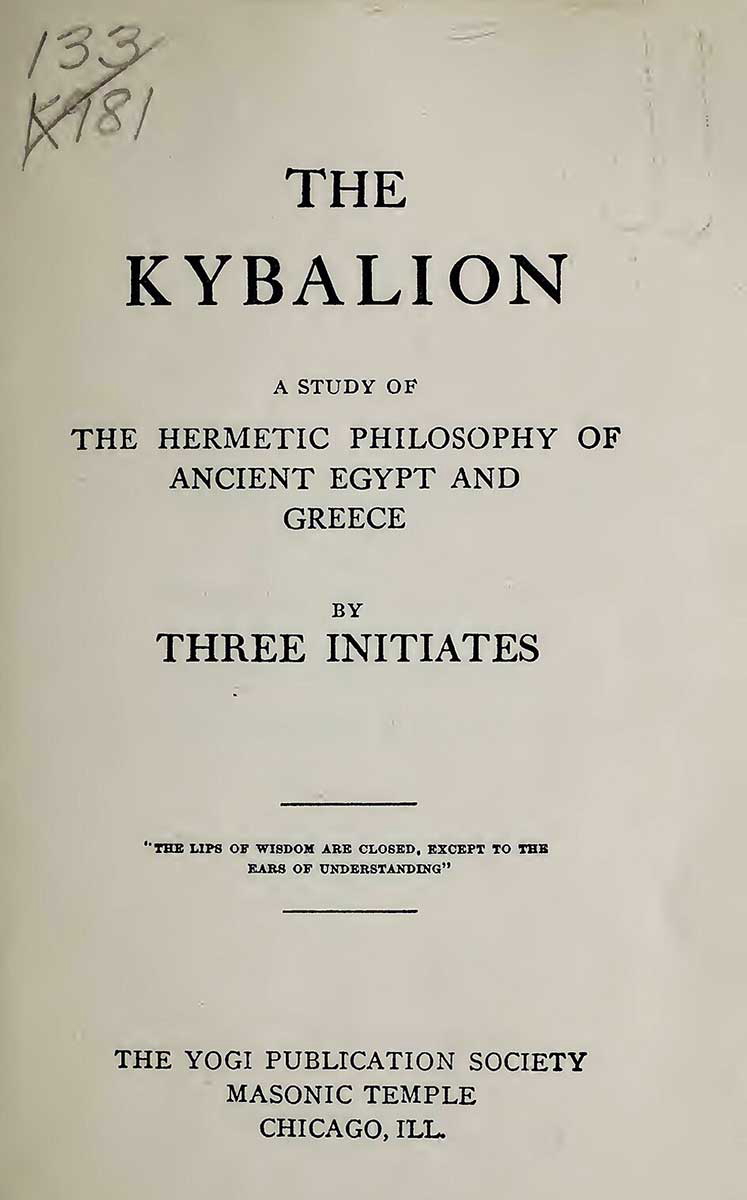

Despite this discretion, Hermetic principles have experienced a resurgence through the New Age movement, which has repackaged ancient concepts, such as “as above, so below,” for contemporary spiritual seekers. Gateway texts such as The Kybalion continue to introduce new generations to these ancient teachings, demonstrating their enduring appeal in addressing fundamental questions about consciousness and reality.

The digital age has also transformed access to Hermetic knowledge, with previously rare manuscripts now widely available online, creating unprecedented opportunities for independent study while challenging traditional initiatory models.

In academia, interdisciplinary approaches have brought fresh perspectives to Hermetic studies, rehabilitating its reputation as a sophisticated philosophical system that anticipated many contemporary discussions about consciousness and material reality.

Significantly, Hermeticism’s emphasis on unity underlying apparent opposites offers a timely framework for addressing modern divisions, suggesting that seemingly contradictory approaches, such as science and spirituality or rationality and intuition, might be reconciled through deeper understanding, providing valuable wisdom for those seeking to develop more holistic approaches to knowledge and being.