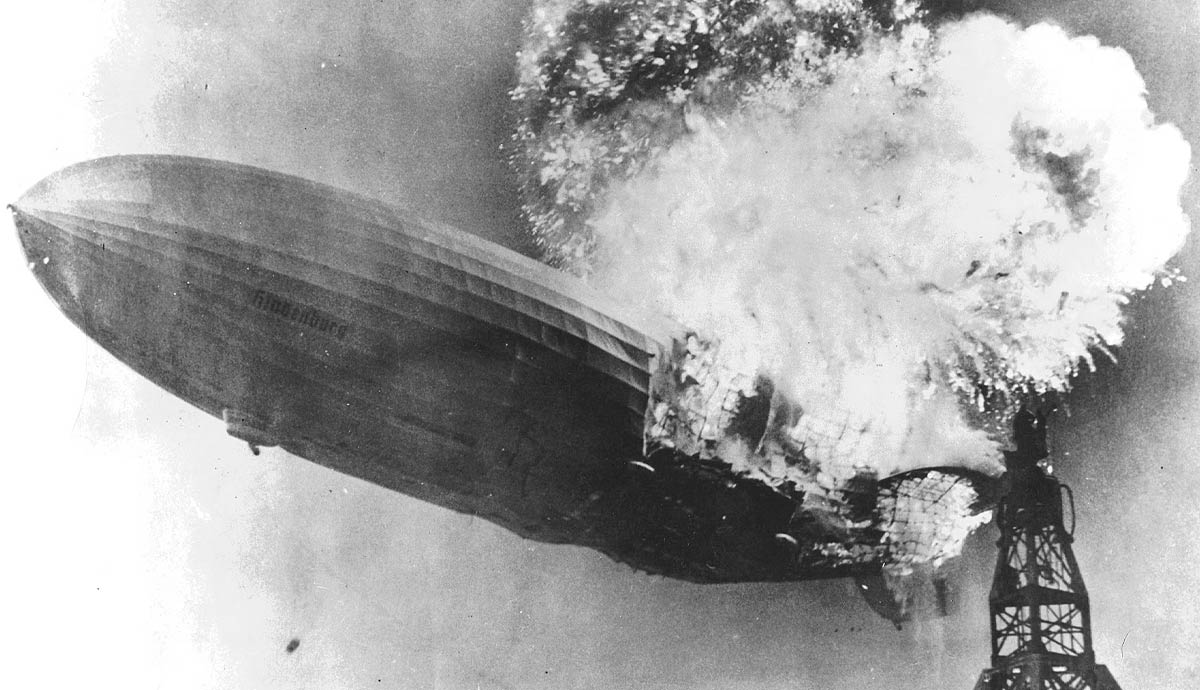

Although the airplane had been invented in 1903 and saw rapid adoption by the world’s militaries during World War I, air travel was far from luxurious during the 1930s. However, a class of luxurious lighter-than-air craft known as zeppelins captured the world’s attention: they were quiet, relatively stable, and gave passengers a far more stately way to travel. As the world struggled out of the Great Depression, would fleets of zeppelins become the new wave of air travel? Tragically, a single disaster on May 6, 1937 doomed this method of transportation. Filled with flammable hydrogen, the luxurious Hindenburg airship caught fire and was quickly ablaze as it attempted to dock over Manchester Township, New Jersey.

Setting the Stage: Infancy of Commercial Air Travel

World War I showed that airplanes were highly versatile, and they were quickly put into use to carry both passengers and cargo after the war. Post-WWI airplanes delivered the mail and were popular in barnstorming shows, where the public could watch aerobatics. These early civilian flights were often dangerous, and there were many casualties. In 1914, the first passenger was flown in the United States, having to sit next to the pilot in the open-air cockpit. By the 1920s, enclosed passenger compartments had been developed, with the Ford Tri-Motor becoming popular with the public.

The late 1920s and early 1930s saw further improvements of passenger airplanes. Development of airliners, enclosed passenger planes, was hindered by the Great Depression, which hurt the revenue of early airlines. Some airlines, such as Delta, had emerged only months before the infamous 1929 stock market crash. Despite Ford Tri-Motors and German-made Fokkers of the 1920s being more comfortable than the open-air cockpits of the 1910s, air travel up through the early 1930s was still noisy, shaky, and not especially fast.

Setting the Stage: Demand for Luxury Travel

Air travel was intriguing, but many who could afford to travel long distances wanted luxury. Roads and trains were significantly improved during the 1920s, raising the expectations of comfort in traveling. The wealthy, therefore, were less inclined to travel by air if it would mean a substantial downgrade in comfort and luxury from a passenger train. For overseas travel, luxury liners provided deluxe amenities, at least for first-class passengers. Since the Gilded Age, the wealthy classes were accustomed to traveling in style.

By 1930, crossing the Atlantic Ocean still took at least four days by luxury liner. Improvements in air travel that could provide comparable comfort but allow for much faster travel than ships could make significant revenue. In 1927, an airplane piloted by American pilot Charles Lindbergh had famously flown nonstop across the Atlantic for the first time. What if passengers could also enjoy nonstop trans-Atlantic flights, all while surrounded by comfort?

Setting the Stage: Powered Airships

While the public mostly focused on airplanes, there were other forms of aerial transportation. The first crewed flight actually occurred in 1783 in a hot air balloon, with heated air providing enough buoyancy to raise a heavy basket. Although novel and initially very exciting, hot air balloons had some major weaknesses: they were difficult to control. In the 1850s, Henri Giffard of France pioneered the first true powered airships, which could be controlled on calm days. During the American Civil War, hydrogen-filled balloons were for aerial reconnaissance, carrying Union soldiers aloft to scout for Confederate movements and signal their compatriots on the ground to respond.

In 1884, the first flights occurred where a powered airship was controlled throughout the entire flight. Thirteen years later, the internal combustion engine was used to power airships for the first time, greatly increasing the amount of control. A few years later, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin revolutionized airships with his rigid-frame design. His first powered airship, or Lutftschiff Zeppelin (LZ), was LZ-1, which was first test-flown in 1900. Future airships quickly took on count Zeppelin’s design of a long, tapered, rigid frame covered by fabric to enclose lighter-than-air gasses.

1910s: First Passenger Airships

Quickly, Zeppelin-style airships were improved for greater stability and maneuverability. In 1911, the first passenger zeppelin, LZ-10 Schwaben, began service. Passenger service by Zeppelins was halted by the outbreak of World War I in 1914, with the airships being transferred into wartime service. During the war, German Zeppelins proved far more effective than French dirigibles, with the German airships almost doubling the speed of their Allied rivals. Zeppelins could be used for aerial reconnaissance and were considered successful. Some sixty were put into German service during the war; one set a record of 95 hours in flight on a mission to resupply German troops in East Africa.

After the war, passenger service returned in 1919, and newer Zeppelins saw further technical improvements. LZ-120 Bodensee, equipped with four powerful engines, could reach 80 miles an hour, making Zeppelins a close rival to airplanes of the era. However, Zeppelins were soon transferred to France under the Treaty of Versailles, which stripped Germany of its war-making equipment. Since Zeppelins had been used to bomb France and England from the air, they were seized as reparation payments. Only in 1926 was Germany allowed to resume building airships, which it did.

1919-1930s: Airship Successes

The success of the German-made Zeppelin, both in civilian transportation and as a military craft, was quickly noticed by the Allies of World War I, including the United States. In 1923, the first American-made Zeppelin was launched, with its design obtained by reverse-engineering a downed German Zeppelin that had dropped bombs on England in 1917. Around the same time, an American airship was inflated with nonflammable helium, though most still used cheaper and more available hydrogen. In 1924, the first use of vertical mooring masts allowed Zeppelins to dock without having to land, increasing ease of use.

Later that same year, flights began between New Jersey and Germany, with Zeppelins traveling some 5,000 miles. In 1928, Graf Zeppelin was completed, named after the deceased Count Zeppelin himself. On October 11, 1928, the airship completed the first trans-Atlantic passenger service by flying passengers from Germany to New Jersey. The initial journey was harrowing, with Graf Zeppelin damaged by storms and having to be repaired in flight by a team of four crewmen. When it landed on October 15, the craft was met with cheers; it had reduced by half the amount of time it took all previous passengers to cross the Atlantic by ship.

1932-36: The Hindenburg is Built

The success of Graf Zeppelin, including a 1929 around-the-world journey, led to the creation of more passenger Zeppelins. A new class of airship was developed: the Hindenburg class, which would contain over seven million cubic feet of hydrogen. The choice to use hydrogen was made despite the catastrophic and fatal loss of a British airship, R-101, due to its hydrogen envelope catching fire in 1930. Additionally, Germany could not get enough helium, as the United States controlled all the known major deposits in the world.

As the Hindenburg was under construction, the Nazi government of Germany decided to help fund the project to showcase German technological prowess. By 1935, civilian control had largely been removed from the construction and operation of the Hindenburg. The completed airship was the largest craft ever to fly, powered by four 1,200-horsepower engines. In 1936, the Hindenburg was displayed to the public, including at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. In addition to passenger service, the Hindenburg was intended to be a propaganda tool for Adolf Hitler’s regime.

May 6, 1937: Fateful Flight of the Hindenburg

In 1936, the Hindenburg began passenger service, carrying 51 passengers across the Atlantic in May. One year later, the sight of the giant airship was still a novelty, and its two-and-a-half-day trips across the Atlantic were legendary. On August 10, 1936, the Hindenburg set its speed record for a 43-hour flight between Frankfurt, Germany and New Jersey. Tragically, its 1937 season would be its last: on May 6, 1937, disaster struck. At 7:25 PM, while attempting to dock at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey, the Hindenburg burst into flames while cameras were filming.

Within 40 seconds, the entire envelope of the aircraft was engulfed in flames, and it plummeted to the ground. Thirty-six people were killed, and radio news coverage of the disaster coined the phrase, “oh, the humanity!”

There were hundreds of onlookers, as a massive crew was needed to handle a landed Zeppelin, and US military personnel were quickly on the scene to help with rescues. Amazingly, a majority of the Hindenburg’s passengers survived, but the dramatic news coverage, including video footage, was sensational. Security would be needed afterward to secure the crash site and keep away souvenir-seekers of the downed Zeppelin’s frame.

Reaction to the Hindenburg Disaster

The public was horrified by the sudden disaster, and the emotional coverage of the event by reporters on the scene added to the drama. Although previous airship disasters had not dented public support for Zeppelin travel, the Hindenburg was the first such disaster caught on film. As a result, millions of people in Europe and North America quickly learned about the disaster and came to view hydrogen-filled airships as potential death traps. Investigators struggled to determine the exact cause of the fire that engulfed the Hindenburg, and the complexity of the situation did nothing to calm the public.

Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, said the incident would not dissuade her from flying. Despite tensions between the United States and Nazi Germany, President Roosevelt sent a message of condolence to German dictator Adolf Hitler, who responded with thanks. The disaster effectively ended the airship era, with Hindenburg’s sister ship, LZ-130 Graf Zeppelin, the only one completed after the crash. It had been near completion on May 6, 1937, and was modified to use helium instead of hydrogen to prevent a recurrence of the deadly crash.

1938-World War II: Limited Role of Airships

Increasing tensions between the United States and Nazi Germany meant Graf Zeppelin never received the necessary helium and reverted to using hydrogen. Its final flight occurred on August 20, 1939, less than two weeks before the start of World War II in Europe. Airships designed for passenger use were all declared scrapped by the German military in March 1940 and were dismantled to have their parts used for military equipment. The United States, by contrast, increased its use of airships during World War II.

Airships were used to patrol shipping lanes and coastal areas to detect enemy submarines. These were not true Zeppelins, which had a rigid inner frame, but rather blimps, which were non-rigid and inflatable. Unarmed blimps could spot enemy actions and report them to armed vessels that could respond effectively. Unlike World War I, airships were not used as offensive weapons due to their slow speed and unwieldy profile—they were easy targets for fighter planes and ground-based guns. After the war, the US maintained a small number of blimps, which were permanently retired in 1962.

Today: Any Future for Powered Airships?

In terms of speed, airships are no match for modern airliners. However, the environmental movement has brought back some support for the idea of using lighter-than-air craft. Airliners use a tremendous amount of fuel and emit significant amounts of pollutants. Some analysts feel that helium-filled airships could be greener than airliners. Although they would not be as fast, they could land on more surfaces and thus save money on the need for expensive airport infrastructure.

Combining new helium-filled airships with electric motors, perhaps even solar-powered, would make them an attractive investment for environmentally-conscious companies. Some argue that hydrogen, which is much cheaper to use than helium, could be safely used today. Another avenue for airships is transporting non-perishable cargo, which could travel slower, to areas that are difficult to access by road or train. Whether or not the late 2020s will see a return of commercially viable airships remains to be seen, but it could be an exciting development.