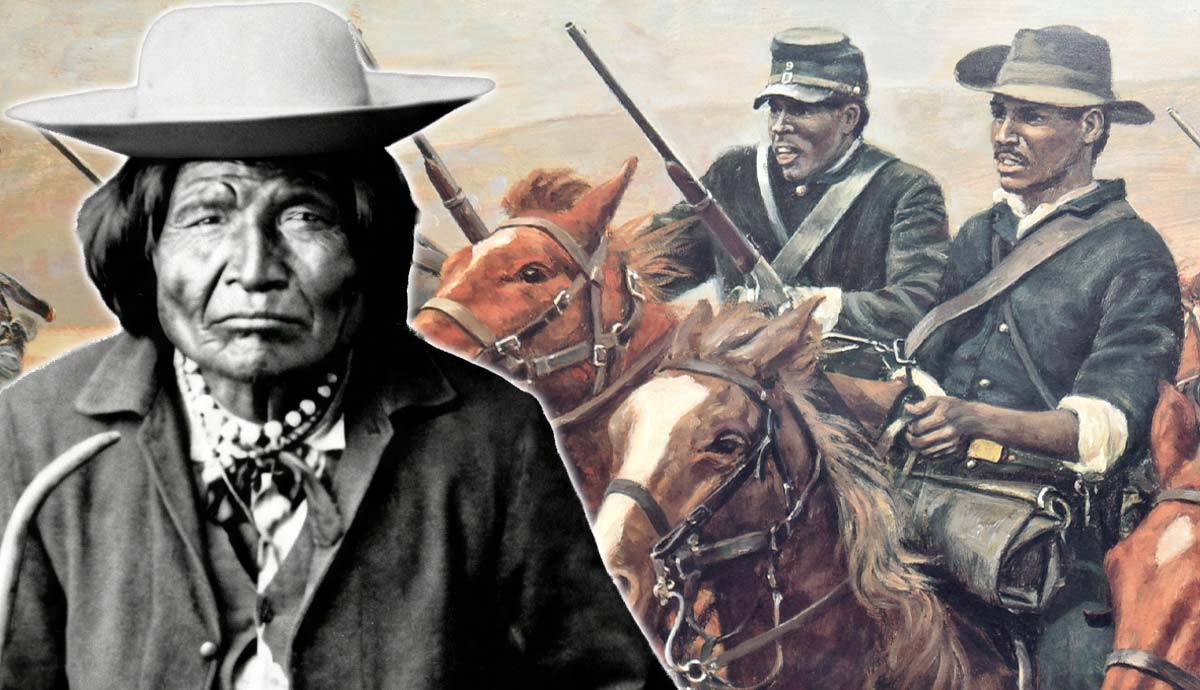

Nana’s story is a typical one for any 19th-century Native American tribe. Years of conflict forced many tribes onto reservations. Several Apache bands, like them, resisted. Their leaders, such as Geronimo, conducted effective guerrilla campaigns. Yet Nana’s campaign would demonstrate what a master warrior could achieve.

By 1881, Nana was ranked as a respected Chiricahua Apache war chief. Yet he was old, at or past seventy, with a lame leg. Angry at how the Americans and Mexicans decimated his people, he sought revenge. Reservation hardships, broken promises, and the death of his brother-in-law Victorio (killed by the Mexican army). With a small band of warriors, typically fewer than forty, Nana unleashed himself in fury, showing what supreme mobility could do.

A Hard-Hitting Summer Begins

Nana started his six-week raid in late June 1881 with 15-40 warriors. This warrior-only band traveled fast, having left families behind. Nana wanted freedom of movement; families or wagons would only be anchors. But logistics rules all conflicts, and he needed supplies. So he headed through southwest New Mexico, southeast Arizona, and northern Chihuahua (Mexico). They first raided rural ranches, stagecoaches, and mining camps-easy targets. This gave the Apache ample weapons, ammunition, and mounts. Extra horses meant Nana’s riders could swap out tired horses to keep moving. For the Apache, speed meant life.

Nana’s looping guerrilla campaign took his warriors through sharp canyons, broken ridges, or dense forest cover. Locations touched on were the Black Range foothills near the Mogollon Mountains for ranches, the Pinos Altos mining camps, or unwary travelers.

Nana’s opponents, the U.S. Army, posses and Mexicans responded quickly. The Army sent units from three forts right as the first raids began.

Shoot, Move, and Fire

Nana certainly appeared to be an uncatchable enemy. The elderly but wily war chief used every tactic gained through decades of war and unmatched knowledge of the terrain. Nana’s primary tactic was mobility and multiple mounts. The Apache raiders rotated horses frequently, setting a pace that stunned his pursuers. Like the Mongols centuries earlier, the Apache lived in the saddle, using nearly impassable terrain, such as volcanic badlands or ridgelines, to foil their enemies.

Importantly, the impaired, arthritic Nana never stood his ground, knowing when not to fight, preferring ambushes or hit-and-run tactics. The Apache remained irregular by doubling back or disappearing into side canyons. They often struck from above, firing and then vanishing.

The slippery Apache foiled Mexican and Americans alike. Raids took only minutes-Nana never strayed from this tactic. They sought food, ammunition, or horses. Soldiers and possies alike tried enveloping movements. Nana drew on his bag of tricks, using tactics like false trails, breaking into smaller groups, or decoys. The Apache stymied every trap. Nana’s group struck across New Mexico, Arizona, and Mexico. Such unpredictability gave Nana the psychological edge, demoralizing his chasers. His tactics forced the Army to spread its soldiers across a huge region.

Pursuit, Politics, and No Luck

For two frustrating months, everyone tracked Nana’s Apache. Nana’s band struck so fiercely, killing and taking supplies. Prior to Nana’s raid, the U.S. and Mexican governments reached an agreement allowing cross-border pursuits. Each shared information about the Apache, but it was always late. Despite attempts at coordination, both accused the other of not doing enough or of allowing the Apache to escape. Neither could fathom that Nana’s warriors traveled up to fifty miles a day.

Even the famed Buffalo Soldiers failed to intercept Nana. The Apache war chief fought only at his discretion, as on August 12, 1881, at the Battle of Carrizo Canyon (New Mexico). Here, Nana ambushed 10th Cavalry troopers, his 40 troopers against the 18 Buffalo soldiers.

Nana waylaid the soldiers upon entering the narrow canyon entrance, firing rapidly. Eventually, a small group of soldiers gained the hills above under fire. They rained lead down on the Apache, allowing their comrades to retreat. This marked the last battle of Nana’s revenge. Nana made for the border, crossing more than 60 miles at their usual speed.

A Lesson Delivered

Carrizo Canyon marked the end of Nana’s summer raid. During the season’s hottest months, the nearly blind, arthritic Apache chief’s small warband kept nearly 1,000 soldiers at bay. He killed at least 30 people in his raids, fueled by rage. Nana traveled 1,000 miles to raid or clash with soldiers, often disappearing quickly. He demonstrated that knowledge, tactical knowledge, and grit can outweigh numbers and firepower.