When Tomáš Masaryk, Edvard Beneš, and Milan Rastislav Štefánik came together to create the independent state of Czechoslovakia in 1918, they proved to be some of the most successful nationalist leaders of the 20th century. The creation of Czechoslovakia (1918-1992) was the culmination of the rise of nationalist movements in the 19th century and the fall of old multinational empires after World War I.

Czechs and Slovaks in the Habsburg Empire

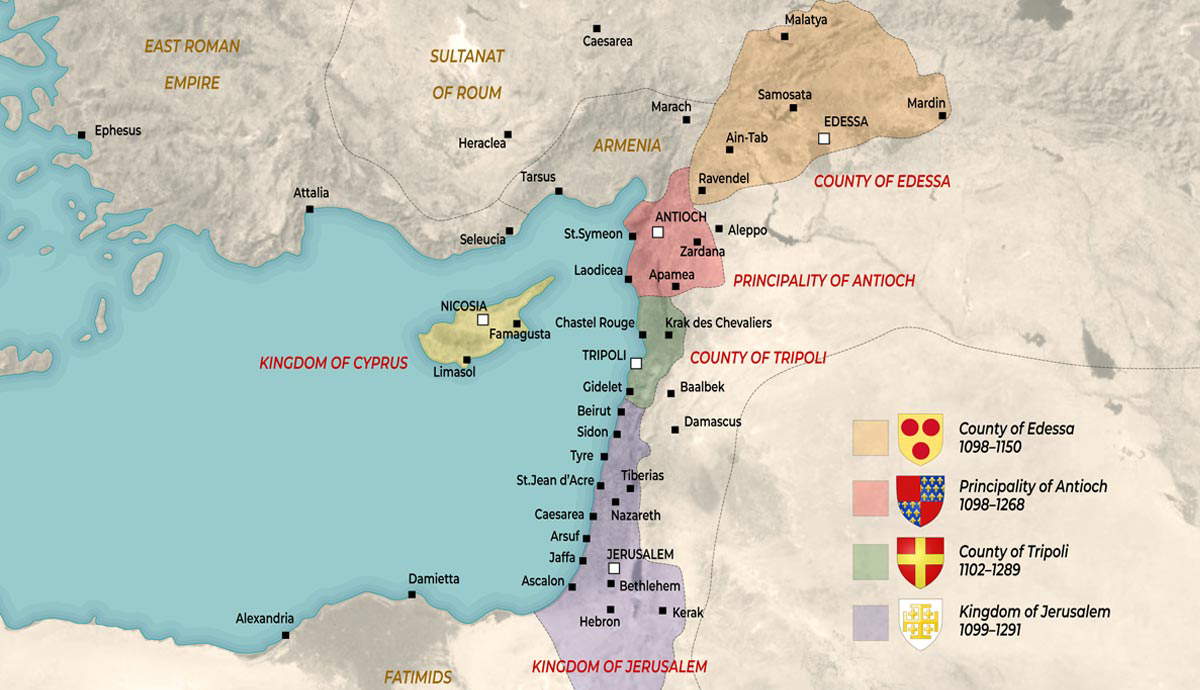

From 1804 to 1918, the Austrian Empire under the Habsburg monarchy ruled over much of Central Europe. The empire was home to a number of different nationalities ruled by a central government in Vienna that sought to either repress or accommodate ethnic minorities. Two large communities within the empire were the Czechs and Slovaks. While these Slavic peoples once lived in the independent states of Bohemia and Moravia during the Medieval period, by the 19th century they had been ruled by Germans and Hungarians for several centuries.

In 1910, there were 2.1 million Slovaks living in the empire. They lived in territories controlled by the Hungarians such as Upper Hungary and the Carpathian mountains. Slovaks had resisted pressure from the Hungarians to undergo Magyarization and forget their Slavic identity. They lived away from urban centers and sought to stick together. Despite heavy immigration to the Americas, most Slovaks remained in the country, hoping to gain autonomy or independence from the governments in Vienna and Budapest.

At that time, there were 6.7 million Czechs in the Austrian Empire. Most of them were located in the crownlands of Bohemia and Moravia. They shared their lands with a German-speaking elite which attempted to Germanize the region. Prague was the center of these ethnic tensions and Austrian elections saw major political disputes between Czech and German parties over the status of these regions. While the Germans claimed that the Czechs were just brickmakers and cooks, they played an increasingly important role in business, industry, and politics. They were considered some of the most advanced people in the Austrian Empire. In the years before the First World War, Czech and Slovak national movements were constantly demanding independence or autonomy at the very least.

The Troika of Czechoslovak Nationalist Leaders

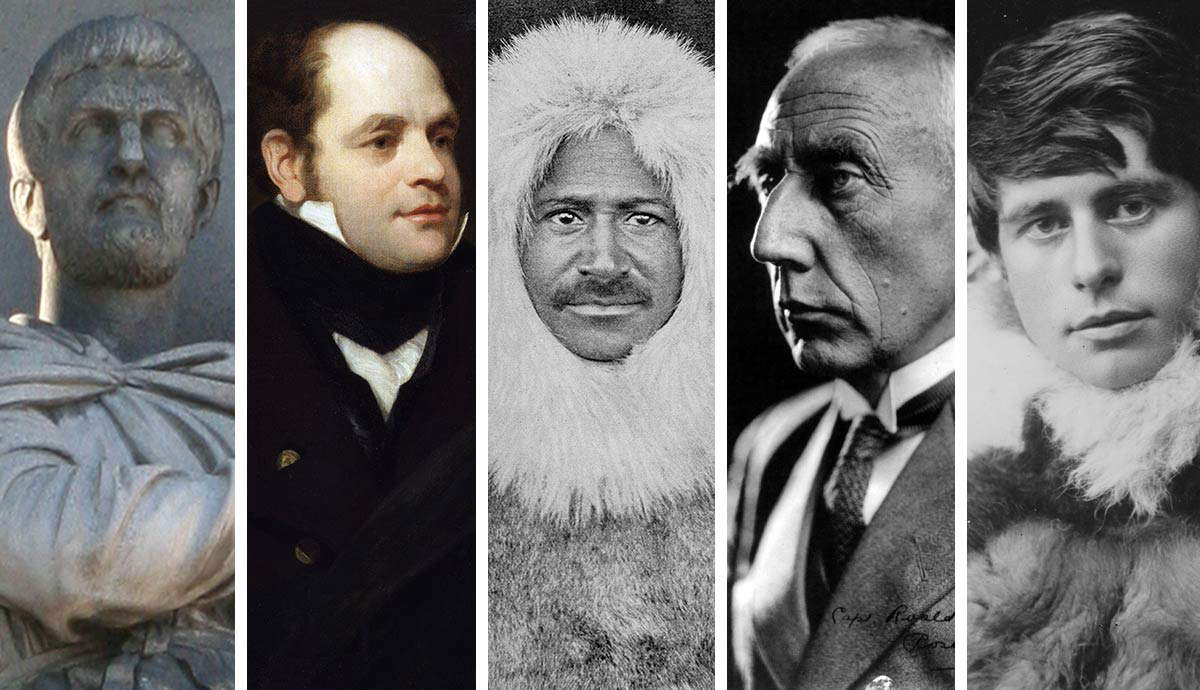

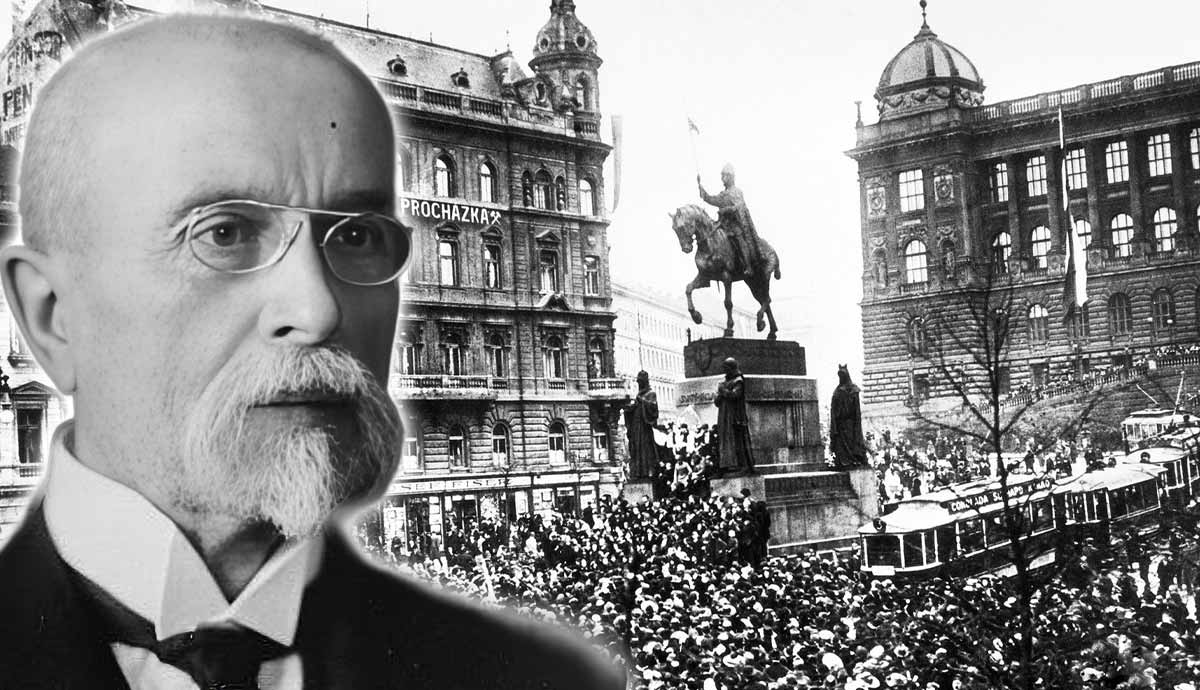

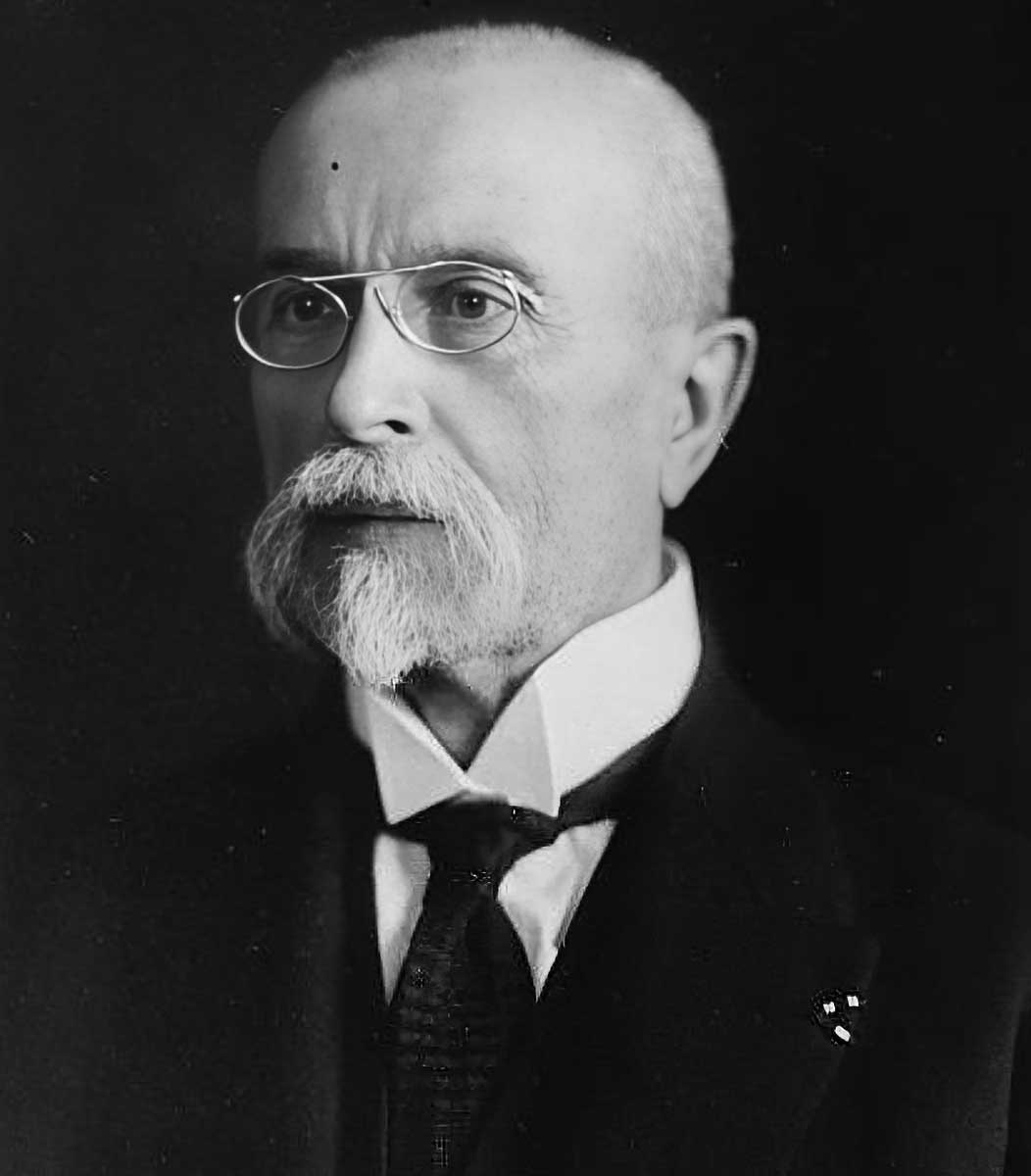

The first of three prominent Czechoslovak nationalists in the early 20th century was the lawyer and journalist Tomáš Masaryk. A man with both Czech and Slovak ancestry, Masaryk had been a representative of the Young Czech Party and the Czech Progressive Party in the Austrian Reichsrat. He was regarded as an unorthodox and colorful individual who defended a Jewish man falsely accused of murder. He opposed the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908, making him enemies throughout the empire. When WWI began in 1914, he went into exile.

Edvard Beneš was a Bohemian born in the 1880s who spent his formative years studying in France and Prague. He came from a poor family that lived a typical existence in the Bohemian countryside. He was a strong supporter of Slavic causes in the Austrian Empire and publicly promoted the cause of Czechs and Slovaks. When Masaryk went into exile, Beneš kept in touch with him as part of an organization called “Maffia”. He subsequently left the country to advocate for the Czechoslovak cause.

The last of the three Czechoslovak founders was Milan Rastislav Štefánik. A Slovak from a small village, he studied construction engineering in Prague and started training to become an astronomer. He was briefly a student of Masaryk and became convinced that Czechs and Slovaks should be united as one people. His need to travel frequently as an astronomer to make observations meant that he became a French citizen right before WWI. All three figures had grand ambitions of a nation uniting Czechs and Slovaks and they desired to work together to make that happen.

Czechs and Slovaks in WWI

When Emperor Franz Joseph I ordered the empire to mobilize to fight the Entente powers at the start of World War I, Czechs and Slovaks found themselves subject to conscription. Some willingly joined, believing that the empire was justified in going to war. Many others were reluctant, especially when they were sent to fight their fellow Slavs in Russia and Serbia. Some one million Czechs and Slovaks found themselves fighting on all sides of the war.

While Vienna portrayed the war as vital for the survival of the empire, many Czechs and Slovaks saw the war effort as impeding their national dreams of statehood. The Entente posed no threat to the traditional Slovak and Czech homelands and the costs of the war heavily impacted communities throughout the empire. War taxes reduced the income of Czech and Slovak families while conscription tore families apart. This in turn led to desertion and mutinies.

During the war, exiled Czechs and Slovaks vowed to assist the Entente in return for support of their national ambitions. Štefánik joined the French Army as a pilot and urged other Slovak exiles to do the same. Every major Allied power lobbied Czechs and Slovaks to desert the Austrian ranks. These efforts had an effect; part of the reason the Austrian army collapsed at the end of the war was due to ethnic tensions within the ranks. They were assisted by Beneš’s organization “Maffia” which aimed to overthrow the empire. Additionally, armed forces of Czech and Slovak exiles began to coalesce to defeat the Central Powers.

The Czechoslovak Legion

Throughout much of the war, the Czechoslovak National Council argued for the creation of an armed force of Czechs and Slovaks that could fight for their homeland. Negotiations were time-consuming because the Entente was not convinced that the Habsburg Empire ought to be dissolved after the end of the war. After much deliberation and debate, Allied commanders actively began recruiting Czechs and Slovaks into their respective armies. In 1916, the French created several regiments of Czech and Slovak dissidents. In Italy, autonomous Czech and Slovak units arrived on the battlefield in 1918.

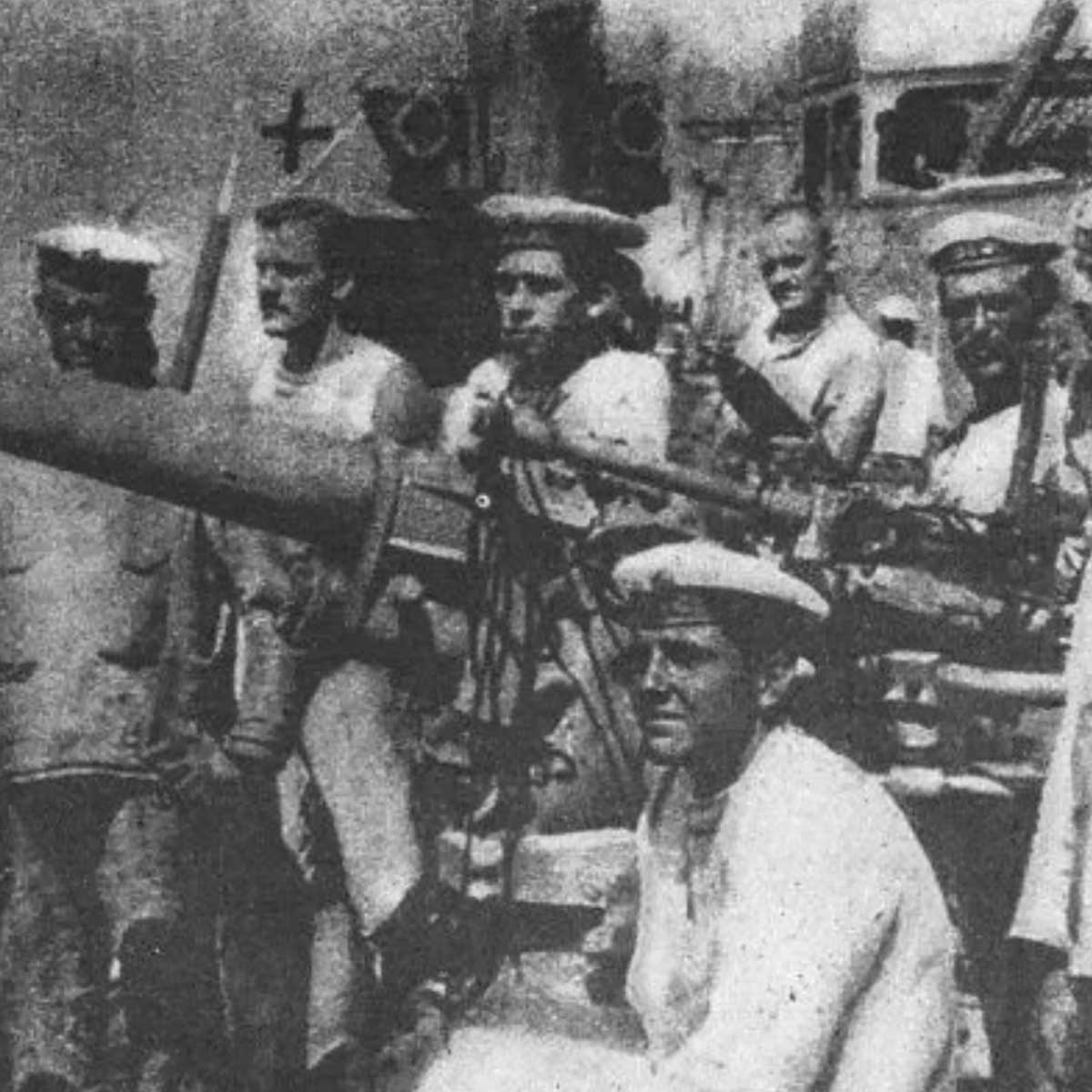

While the Western Allies were sympathetic, the Russians were the most willing to promote Czechoslovak nationalism. As soon as the war started, units composed of Czech and Slovak prisoners of war were formed to fight with the Russian Third Army. They gained a reputation as some of the most effective formations in the Russian army, even when the Russian army began to break apart during the revolutions of 1917. By the time Russia exited the war by signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany in 1918, there were 40,000 Czechs and Slovaks in this unit, known as the Czechoslovak Legion.

As the Russian empire crumbled and the new Russian government collapsed, the Legion insisted on the right of passage to their homeland. When the Bolsheviks rose to power, they signed the Penza Agreement, allowing the Czech Legion to take trains to Siberia and evacuate. However, the Legion became trapped during the Russian Civil War and ended up having to fight the Bolsheviks alongside Admiral Alexander Kolchak’s White Army. They only returned to Czechoslovakia in 1920 at the end of the conflict.

The Declaration of Independence, 1918

As the First World War was coming to an end in 1918, Vienna’s empire began to experience internal chaos. Heavy casualties and repeated defeats led to serious disorder and encouraged support for separatism. Masaryk, Beneš, and Štefánik saw opportunity where the Austrians saw disorder. The Czechoslovak National Council increased its lobbying efforts and saw hope in Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, which supported self-determination for people in Europe. Despite some efforts by Slovaks to form their own state, many others believed that their fate was linked with the Czechs.

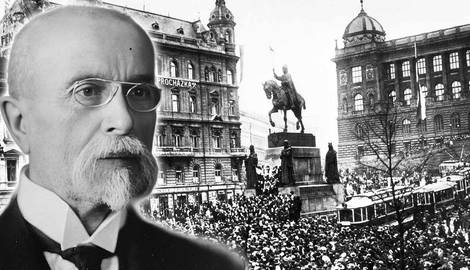

In 1918, Czech and Slovak representatives met in Pittsburgh in the United States and signed an agreement announcing their intention to create an independent state. This was followed by the Washington Declaration on October 18, 1918. This statement, which had the blessing of the Western Powers, was the formal declaration of independence of Czechoslovakia by the Council. However, the actual day of independence would come on October 28, when the Czechoslovaks received permission from Vienna to form their state.

Upon the declaration being read aloud in St. Wenceslas Square in Prague, the local population reacted with jubilation. Dr Isidor Zahradník, a future government minister, gave a speech to thunderous applause stating “We are breaking our chains forever in which the faithless, foreign, immoral Habsburgs have tormented us. We are free!” German signs were torn down, people brought out new flags of Czechoslovakia, and Austrian officials and troops immediately evacuated from the newly independent country. This day marked a new era in the history of Central Europe, precipitating the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with the effective abdication of Emperor Karl I on November 11, 1918.

Building State Institutions

Declaring independence was easy enough; developing a state proved more challenging. The new state faced challenges from its neighbors on its borders, the economy was weak after years of war, and the threat of Communism was real. When negotiators from around the world met at the Conference of Versailles, Czechoslovak representatives attended to gain recognition for their borders, which was granted at the Treaty of St Germain. There were serious fears about Hungarian revanchism, Polish expansionism, and Pan-Germanism.

The new republic was supposed to consist of five main territories: Bohemia, Moravia, Czech Silesia, Slovakia, and Carpathian Ruthenia. The new Czechoslovak armed forces battled a Hungarian attempt to conquer parts of Slovakia. Additionally, pan-Germanic political factions tried to get Bohemia to secede and join a united German-Austrian state. The police and army crushed this separatist attempt. Lastly, the new Polish state sought control over parts of Silesia. The Czechoslovaks prevailed in these fights and consolidated their national sovereignty.

While the new state fought for sovereignty, a new government was formed. Czechoslovakia was a multiparty democracy in the interwar period in accordance with the wishes of its founding leaders. Both Czech and Slovak were designated as official languages. Major social investment stimulated the economy and gave people confidence in the state. Equal rights and suffrage were granted to all. Masaryk became president, Beneš became foreign minister, and Štefánik war minister. The first election in 1920 saw 22 parties compete in the National Assembly. This set the tone for the country’s future and resulted in 20 years of political stability until 1938, when Nazi Germany annexed the Sudetenland.

Following six years of German occupation during World War II, Czechoslovakia regained its independence and prewar president Edvard Beneš returned to office. After Beneš’ death in 1948, Czechoslovakia became a communist country and remained so until the Velvet Revolution of 1989. The Czechs and Slovaks separated in 1992 on amicable terms in the so-called “velvet divorce.”