The National Socialist movement acquired an air of respectability through their collaboration with the established elites of right-wing politics. This was a situation of give and take. If the right-wing Establishment was to work with the Nazis, they had to be reassured that the National Socialists harbored no “class-war tendencies” (Noakes and Pridham, 1983). For this reason, Hitler positioned himself as a bastion against the advance of Marxism — the nemesis of right-wing politics.

The Beer Hall Putsch

“What a combination,” wrote prominent Nazi Kurt Lüdecke. “Ludendorff, the General, with all that name implied of caste and authority, and Hitler, the dynamic corporal, coming from the people!” (Lockenour, 2021). The Beer Hall Putsch of 1923—an early attempt of Hitler’s to seize power through revolutionary force—failed miserably. But to be involved in a putsch attempt with General Eric Ludendorff, was by no means an inauspicious way for an aspiring demagogue to make his mark on public life.

Eric Ludendorff had been one of the two highest-ranking German officers during WWI — the other, Hindenburg, became the nation’s most popular and influential figure after the war. While Ludendorff was never quite as revered as Hindenburg, he was nonetheless a household name and well-liked. The respect that the old general commanded is reflected in the words of the police officer who arrested him after the Putsch: “Excellency, I must take you into custody” (Noakes and Pridham, 1983).

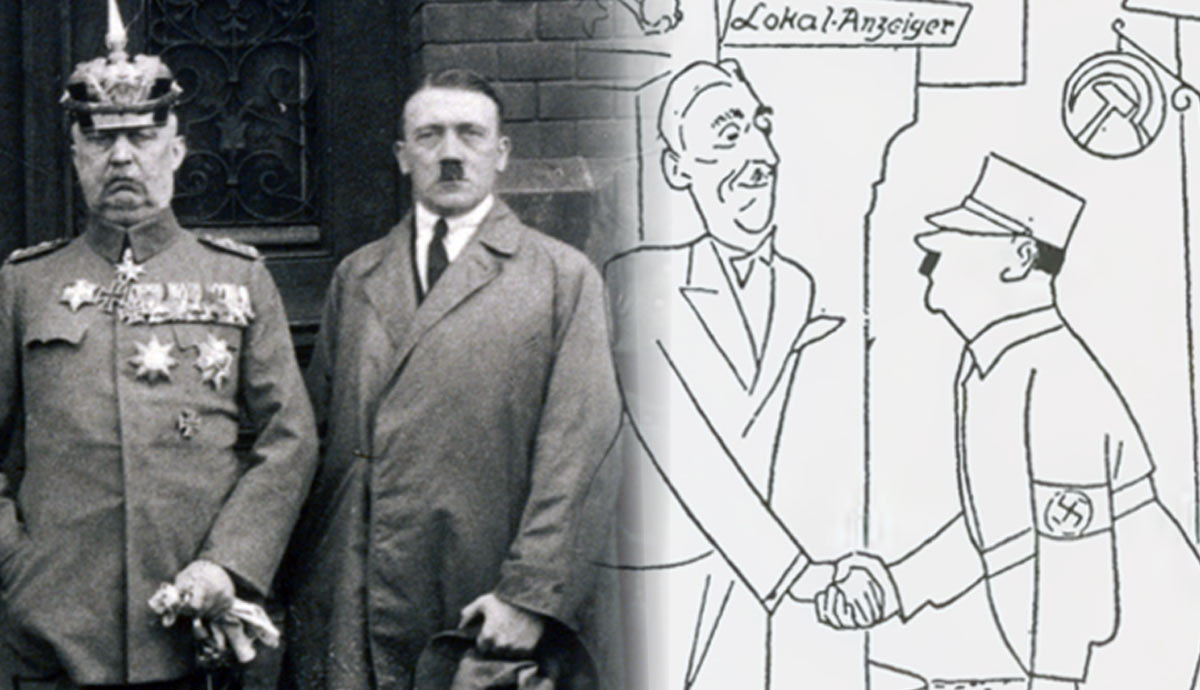

Ludendorff’s presence at the Putsch added to the enormous public interest in the case. An image from the trial shows Hitler standing close to the general, who sports the regalia of an aristocratic officer class. This proximity would have caused right-wing sections of the public to view Hitler as more than just a leader of a band of thugs.

After the Putsch failed, during his trial, Hitler proclaimed himself to be the “destroyer of Marxism.” “I am no monarchist,” he said, “but ultimately a Republican…Ludendorff is devoted to the House of Hohenzollern. Despite our different attitudes we all stood together” (N and P, 1983). This collaboration was a sign to the old right that their differences with the National Socialists were not insurmountable; Hitler could be a genuine political force and a useful ally in their fight against the left wing of German politics.

Winning Power by Constitutional Means

After the failure of the Putsch, the National Socialists committed to winning power by constitutional means. When prominent Nazi Ludecke visited Hitler in prison in 1924, Hitler told him that his new battlefield would be the Reichstag (German parliament): “Instead of working to achieve power by armed conspiracy, we shall have to hold our noses and enter the Reichstag against the Catholic and Marxist deputies” (N and P, 1983). This made the cultivation of a reputable public image extremely important, particularly as alliances were key to political success in Weimar Germany.

Identifying the Catholic Center Party and the Left as his opposition, Hitler realized that the Right were his natural allies. To court the right-wing Establishment, he emphasized the “National” elements of his party and was careful to keep the “Socialist” element in check. Hitler had to distinguish his party’s Socialism from the “Marxist” Socialism of the Social Democrats, or the Communism of the KPD.

Above all, Hitler wished to avoid criticisms of the kind which would later be levied at the Nazi Party by the highly influential right-wing President Hindenburg. In 1931 the revered president was angry at having been disrespected by “scandalous demonstrations of National Socialists.” The giant at the head of the right-wing Establishment said he feared that the Nazis “were more socialist than nationalist,” and that their “behavior in this country he could not approve” (Dillon, 2024).

Socialism and anti-social behavior were inextricably linked in the mind of the president; a connection that existed not just in his mind, but in the minds of those on the Right more generally. To gain access to the halls of power, Hitler had to distance himself from Socialism as understood by those right-wing elites who held the keys. This was no easy task for the leader of a party named the National Socialists.

Distance From the Left: The Nazis Court the Right

In 1926, the Social Democratic Party proposed a referendum to confiscate the property of princes. Many Nazis would have expected Hitler to be in favor of the referendum — they viewed the princes as idle beneficiaries of the old imperial order. However, his response shocked and disappointed many of his followers. A diary entry written by Joseph Goebbels captures this sense of frustration and disbelief: “Hitler speaks for two hours. This pretty nearly finishes me…Law is law. Also for the princes. Question of not weakening private property. Horrible!” (N and P, 1983).

To Goebbels’ disgust, Hitler was instructing his party leaders to respect the law and private property and oppose the referendum. These instructions were intended to distance the party from the “Marxist” Social Democrats and avoid offending the sensibilities of the right-wing Establishment — many of whom were, if not princes, aristocrats themselves.

In 1928 Hitler continued to create an image palatable to the right-wing Establishment, clarifying that the Nazi Party “accepts the principle of private property.” He reassured his wealthy collaborators that the Nazi policy of “confiscation without compensation” had not been aimed at them, but “against Jewish companies” (N and P, 1983). 1928 was a key moment for Hitler in his mission to gain political power. It was the year that the media magnate Alfred Hugenberg took over the largest right-wing party in Germany and reached out to Hitler as an ally.

Their collaboration in a nationwide campaign gave the Nazi Party an air of respectability as a legitimate political force. Furthermore, this collaboration gave Hitler access to “a network of little newspapers and news sheets,” which began “broadcasting his ideas at the cost of Herr Hugenberg’s party funds” (Dillon, 2024). In order to reap these benefits, Hitler ensured that his party was not associated with left-wing economic policies.

A Political Parasite: Collaboration With the DNVP

The Nazis’ careful avoidance of “class-warfare tendencies” proved to be fruitful in their collaboration with Alfred Hugenberg. Having been elected chairman of the largest right-wing party in Germany (the DNVP), Hugenberg cut ties with his party’s center-right allies and began to collaborate with Hitler and the Nazis. According to the British ambassador to Berlin at the time, the stupidity “of Herr Hugenberg in… subsidizing Hitler’s following” accounted for a share of the Nazi Party’s electoral success in 1930 (Dillon, 2024).

Through their collaboration with the DNVP, the Nazis had acquired the appearance of a legitimate political force. Shifting his party to the radical right and providing the Nazis with a platform to campaign from, Hugenberg found himself outflanked by the more radical and increasingly popular Hitler. Like a parasite, the strength gained by the Nazis through their collaboration with Hugenberg’s party weakened the DNVP and led to its demise.

In the 1930 elections, the Nazis increased their share of the vote from less than 3% to almost 20%. They became the second-biggest party in Germany, and the largest party on the Right. More voters transferred their support from the DNVP to the Nazi Party than from any other party. The right-wing, middle-class demographic that Hugenberg was trying to appeal to was more attracted to the National Socialists. One prominent social commentator at the time went as far as to call National Socialism a “delirium of the German lower middle class” (Harry Kessler, 1930).

Hitler—who Hugenberg had envisaged as the junior partner in their collaboration—had swiftly become more powerful than his establishment patron. The Nazi party had gained immeasurably from their collaboration with the DNVP, at the latter’s expense.

“The Best Part of the German Aristocracy”

In July 1932, the Nazi Party became the largest in Germany for the first time—winning 37% of the vote—but President Hindenburg refused to make Hitler Chancellor. Instead, the Prussian nobleman Franz von Papen was given the lead role and asked to form a cabinet. Nazi head of propaganda Goebbels called for an all-out attack on “the Papen Cabinet” to expose them as “a small feudal clique.” Rudolf Hess—Hitler’s right-hand man—warned against this strategy. He reminded the party of the electoral damage that would come from “showing class-war tendencies” and scaring off right-wing voters.

Hess warned the Nazi press that “It is inexpedient to gear the campaign to the slogan: ‘Against the rule of the barons.’” An extract from the diary of a middle-class German woman confirms Hess’ fears: “We know this language only too well from Socialist and Communist papers; we don’t want to hear it from Goebbels!” (N and P, 1983).

Goebbels clearly took note of Hess’s warning. In October he (perhaps reluctantly) backtracked, warning Nazi representatives that their anger at Papen “must not lead to a complete condemnation of all employers,” and that they must not “spread details of the unjustifiable salaries of leading industrial figures.” Nor should “the fight against the Papen Cabinet…develop into a fight against the aristocracy as such,” as “the best part of the German aristocracy fights in our own ranks” (N and P, 1983). The Nazi Party had to avoid offending the right-wing Establishment figures who had been and still would be key to their rise.

In the intrigue that surrounded Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor in 1933, the support of key figures in the Establishment (including Papen) proved essential. By consistently checking their own tendency to attack big business and the aristocracy, the Nazis acquired the air of respectability necessary to capture the German state.

Bibliography

Noakes, Jeremy; Pridham, Geoffrey (eds.). Nazism 1919-1945: Volume 1, The Rise to Power 1919-1934, (Exeter, 1983).

Kessler, Harry. Berlin in Lights: The Diaries of Count Harry Kessler (1918-1937), (London, 1971).

Dillon, Chris (ed.), BKF Source Pack (London, 2024).