First as a kingdom, then as a republic, and then as an empire, the Roman state lasted for well over a thousand years, defeating and incorporating many different nations into its whole. At times it was immensely powerful, conquering and subjugating enemies with shows of imperial power, and other times it was weak, suffering from economic and political disasters that seemed insurmountable.

The glory that was Rome did not last forever. The world changed, and with it, Rome. Socio-political and economic factors stressed the state to breaking point, and, indeed, beyond it.

This is how Rome fell.

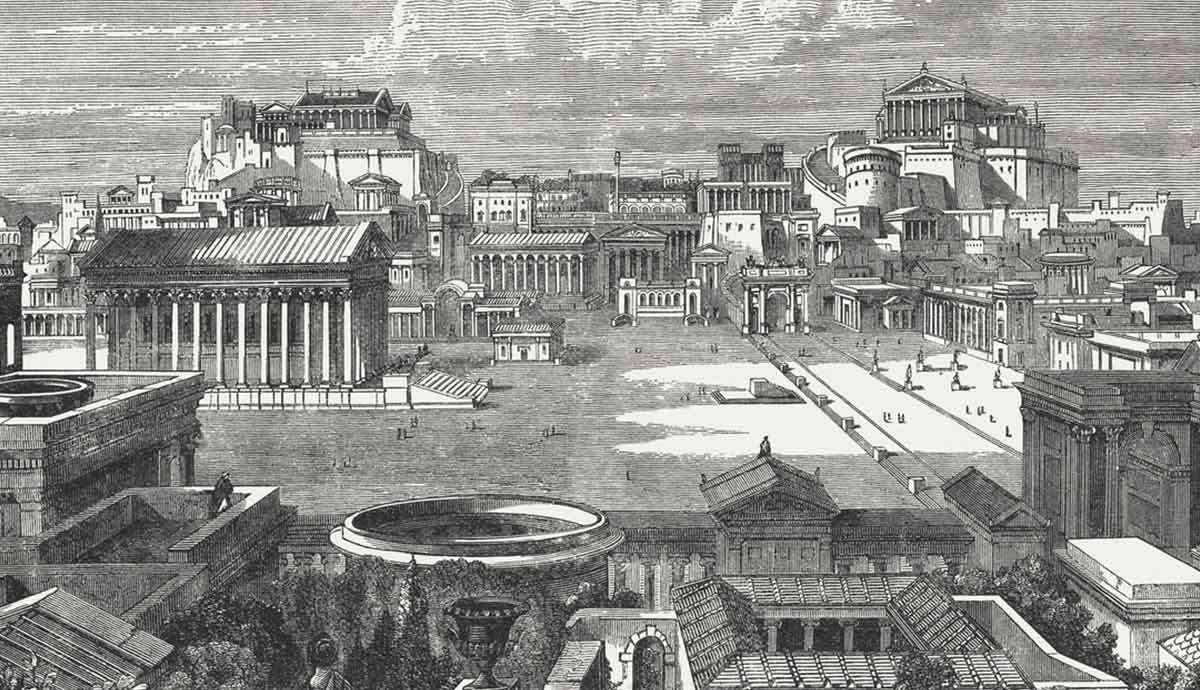

Before the Fall

Rome reached its territorial height during the reign of Trajan (r. 98 CE to 117 CE). He was the second of what was known as the five “good” emperors, and presided over an era of peace, stability, and the military might to expand and defend Rome’s borders. It was a time of Roman dominance, and there was little indication that so many troubles lay ahead.

This era of prosperity is generally seen to have ended with the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180 CE, as his reign was followed by that of his son Commodus, who was a particularly brutal and excessive man, prone to wild displays of violence and a dictatorial style of rule that was marked by intense political intrigue.

While this may not have been the beginning of the end, it can certainly be regarded as the end of a “golden era,” and one in which it became apparent that Rome’s problems were not so far away.

The Crisis of the 3rd Century

Also known as the Imperial Crisis or the Military Anarchy, the Crisis of the Third Century was a period from 235 CE to 284 CE in which the empire suffered economic, military, and political crises that brought it to the brink of collapse. It started with the assassination of Emperor Severus Alexander, and over the course of the next five decades, there were no fewer than 26 legitimate emperors, most of whom were military generals powerful enough to take the title with the backing of the Senate or with enough power from the military.

This period was also marked by civil war, as the empire broke apart, and generals fought for control. In doing so, they neglected the defense of Rome’s borders, and the empire fell victim to raids and invasions from external sources. The crisis also affected Rome’s extensive trade network, generating negative impacts on the financial institutions and economy of Rome.

Rome, however, survived the chaos thanks to the efforts of Diocletian, who split the empire into two administrative halves and instituted the Tetrarchy (a four-ruler system) in which each emperor had a junior emperor to advise and act as a successor. He reorganized the empire’s bureaucratic systems and presided over major military victories against Rome’s external threats.

Through Diocletian, the Roman Empire was given a lease on life, but it was not to last.

378 CE: Adrianople and the Gothic Problem

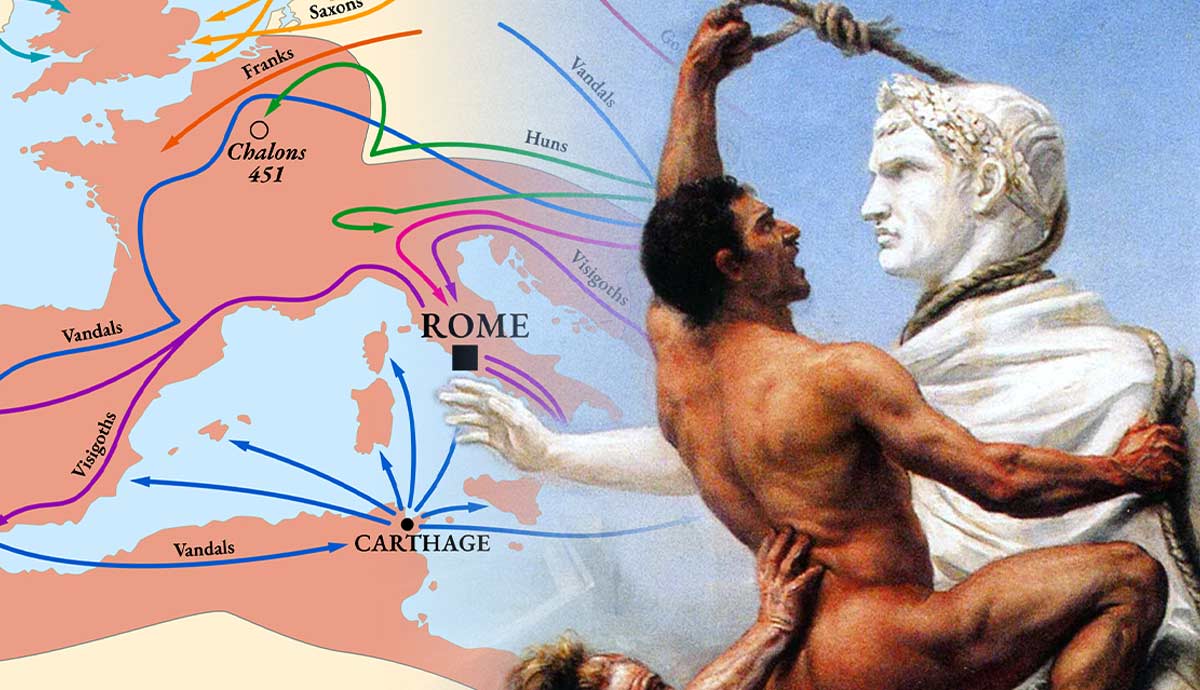

In the last century of Rome’s existence as a powerful empire, its social makeup changed dramatically. Germanic peoples pressed on Rome’s borders, not just looking to expand their own borders, but searching for a place to call home. Resistance to this dynamic and the refusal to respect the demands of these people can be considered the final catalyst that decided the empire’s fate.

Displaced by the Huns, the Goths, in 376 CE, requested the aid of the Romans, asking them for the right to settle in Roman territory. The Romans agreed, but treated the Goths with disdain. The Goths’ hardships were dire, and they faced famine, only to be told that they should sell their children into slavery to stave off starvation.

Ultimately, the mistreatment led to revolt, and the Goths won a stunning victory at Adrianople in 378 CE, defeating the Romans and killing Emperor Valens in the process. This battle indicated that the Goths were not to be taken lightly, and their presence in the empire was of significant importance, which commanded respect. Sadly, for the Romans, this dynamic was ignored by many leaders in the decades that followed.

410 CE: The Eternal City is Taken

Allowed to settle within the empire, many Germanic tribes became foederati, allied to Rome and providing military assistance, but still thought of as second-class citizens. Their grievances were often the result of harsh treatment. Of major note was the Battle of Frigidus in 394 CE, in which the Visigoths, a Germanic people serving as foederati, were used as disposable infantry and suffered immense casualties as a result.

Years of struggling for justice culminated in the Visigoths, under the leadership of Alaric, marching into Rome on August 24, 410 CE. The sacking was rather mild in relative terms, with only a handful of buildings burnt, and most of the populace treated reasonably well considering the circumstances. And although the capital of the Roman Empire had been moved to Ravenna, the occupation of their symbolic center was a great blow to Roman prestige, signaling that perhaps the Roman Empire was not the eternal powerhouse that many believed it was.

The Huns

In the last decades of the Roman Empire’s existence, the borders were under continuous pressure from foreign forces. The Huns were a prime exemplar of this dynamic, and caused havoc, driving nations before them and causing a mass refugee crisis as various peoples sought safety within Rome’s borders.

Under the leadership of Attila, the Huns were a huge threat to Rome. They were defeated by a coalition of Romans and Visigoths at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451 CE, but the threat persisted. Attila was still able to invade Italy, but is thought to have been defeated by pestilence, as well as the diplomatic efforts of Pope Leo I.

Attila’s death in 453 CE preceded a complete collapse of the Hunnic Empire, and it ceased to be a significant danger to Rome in the years that followed. The damage the Huns had done to Rome, however, proved that Rome was certainly not the power it had been in previous centuries.

455 CE: The Vandals Sack Rome

Of great danger to the authority of Rome were the Vandals, a Germanic people, who had crossed into North Africa and occupied large swathes of Roman territory. A peace treaty between the Romans and the Vandals included the promise of a marriage between the Vandal leader, Gaiseric’s son, Huneric, and the daughter of the Roman Emperor, Valentinian III, Eudocia. Valentinian’s successor, however, Petronius Maximus, broke the treaty by marrying Valentinian’s widow, Licinia Eudoxia, and forcing her daughter to marry his son.

The Vandals invaded Italy, and Maximus attempted to flee the city of Rome, but was discovered and lynched by an angry mob. The Vandals spent two weeks in Rome after capturing it, plundering it of its valuables, and taking captives as slaves. Despite the destructive nature of this event, it would have been worse if not for the intervention of Pope Leo I, who again saved Rome from further destruction through diplomacy.

Eudocia, her mother, and her sister were taken captive by the Vandals, and Eudocia married Huneric, to whom she was originally betrothed.

472: Ricimer Takes Rome

After the sack of Rome in 455 CE, the empire went from one crisis directly into another. Emperor Avitus of the Western Roman Empire had little backing from the Senate and was deposed after being defeated by rebel forces at the Battle of Piacenza. Ricimer, a powerful magister militum, the highest military rank, had the political backing to raise his friend Majorian to the position of emperor, expecting the latter to be easily controllable.

Ricimer, who was a Romanized Germanic general, wanted to rule Rome through a puppet ruler, and as Majorian was too independent, Ricimer deposed and executed him. He appointed Libius Severus as emperor and continued to rule through him as a puppet. Libius Severus died in 465 CE and was followed by Anthemius, who had the support of Leo I, the Eastern Roman Emperor (not the same as Pope Leo I!).

In his effort to rid himself of Anthemius, Ricimer besieged Rome in 472 CE. The city fell and was sacked yet again. Anthemius was captured and executed, and Ricimer installed Olybrius as the next emperor, who died just a few weeks later, followed by Ricimer a few weeks after that.

This episode highlights the complete breakdown of Roman authority and characterizes the dangerous chaos of Rome’s echelons of power.

476 CE: The Symbolic Fall of Rome

The year 476 CE resonates powerfully with historians. It is the year that Rome’s last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed. This was the culmination of grudges and a demand for justice emanating from the foederati. Ultimate decision-making in the empire fell to Orestes, the father of Romulus Augustulus, who was just 11 in 476 CE.

Orestes refused foederati demands for compensation for their service, and the foederati declared Odoacer their king. They captured and executed Orestes, after which they marched on Ravenna (the new seat of Roman power) and deposed Romulus Augustulus. Odoacer allowed Augustulus to live comfortably in exile, with a decent pension and a fortified villa in Campania. The Roman Empire ceased to exist as a polity.

Rome After Rome

While 476 CE is cited as the year the Roman Empire fell, the reality is a lot more nebulous. The empire was in decline for a long time, and when the last emperor was deposed, for most people, life carried on as usual. In fact, the capital of the Roman Empire had moved to Constantinople in 330 CE, preceding the split of the Western and Eastern Roman Empires, and from 402 CE, the capital of the Western Roman Empire was moved to Ravenna from Mediolanum, which had been the de facto capital from the end of the 3rd century CE. The Eastern Roman Empire continued to exist as the Byzantine Empire until 1453, when Constantinople fell to the Ottomans.

Despite Roman rule being replaced by non-Romans, much of the Roman Empire continued to exist. Ways of life, languages, culture, and even the Roman Senate continued to exist and evolve, paving the way for Europe’s transition from the Ancient Era into the Early Middle Ages. Odoacer preserved Roman culture and bureaucracy, exercising a great deal of respect and religious tolerance for his new subjects. This dynamic continued under the rule of Theodoric after he killed Odoacer in 493 CE, and incorporated Italy into the Ostrogothic Kingdom.