Birthdays were considered important in the Roman world, and Romans were in the habit of celebrating their own birthday, and those of their nearest and dearest. Roman birthday celebrations would have looked familiar in some ways, as friends were invited over to celebrate and often brought gifts. But birthdays also had an important religious element, with sacrifices to the tutelary god of the birthday boy or girl. When the Republic became an Empire, these rites found their way into the imperial cult on the birthday of the emperor.

Anniversaries in Ancient Rome

In the Roman world, the day that someone or something was “born” was considered important. Rites were conducted annually on the day that a temple was established, considered the birthday of the god of that temple.

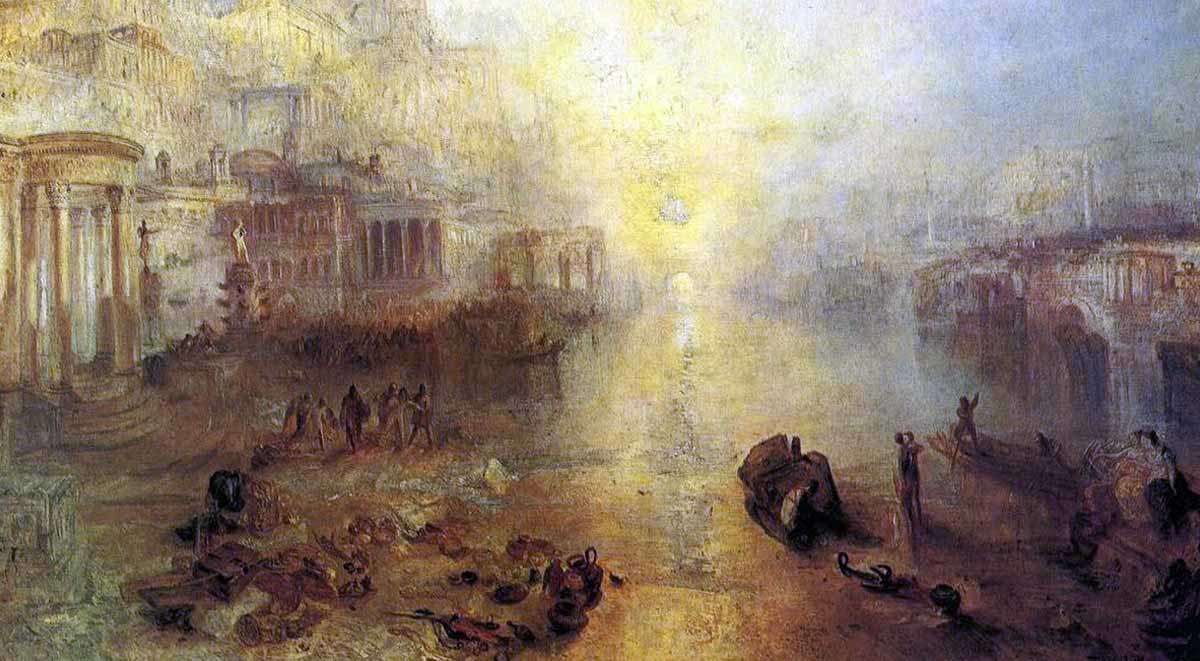

The birthday of Rome itself was celebrated each year on April 21, the date of the legendary founding by Romulus in 753 BCE, although this date was only firmly established in 47 CE under Emperor Claudius. Every 100 (or 110) years, the Romans held the Ludi Saeculares to mark a century of Rome, though emperors calculated the number of years to suit themselves, with Augustus holding the ludi in 17 BCE, Claudius in 47 CE, and Domitian in 88 CE. Philip the Arab held games celebrating a millennium of Rome in 248 CE, with coins exhibiting the number 1001, suggesting that they considered it the first year of a new era. The foundation dates of other cities were also regularly marked with rituals and celebrations.

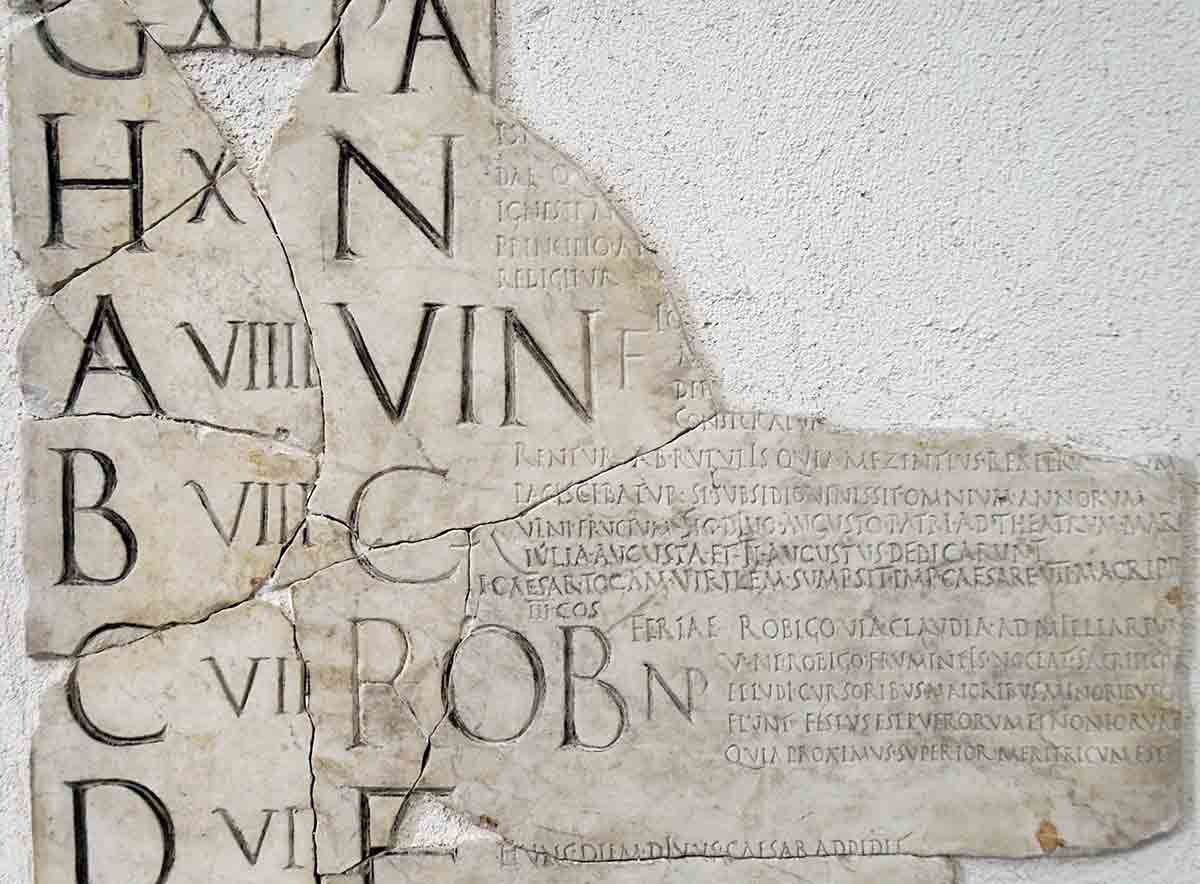

However, it is worth noting that an anniversary was not always celebrated every 365 days. Until the introduction of the Julian Calendar in 45 BCE, Rome used a lunar calendar, or fasti, that quickly fell out of sync with the solar year. The Romans attempted to address this by inserting an “intercalary month” near the end of February, but this was not done consistently as magistrates and priests manipulated the calendar for political purposes.

Julius Caesar reformed the calendar in 45 BCE with a new solar calendar, bringing order to time in the Roman world until the Gregorian Calendar was adopted more than 1,500 years later. But when we say that Julius Caesar died at the age of 55 in 44 BCE, this is more of an estimate. These discrepancies did not seem to worry the Romans, but they can make dating important events difficult for modern scholars.

We know that the Romans also celebrated their birthdays, as the theme is often mentioned in the surviving sources. It was common to celebrate your birthday with religious rites and invite friends over to party, often receiving gifts. People might also choose to conduct religious rituals on the birthdays of the people closest to them, such as lovers or family members. The familia (slaves and freedmen) and cliens (dependent clients) of important men were also expected to conduct rituals on the birthday of their patronus.

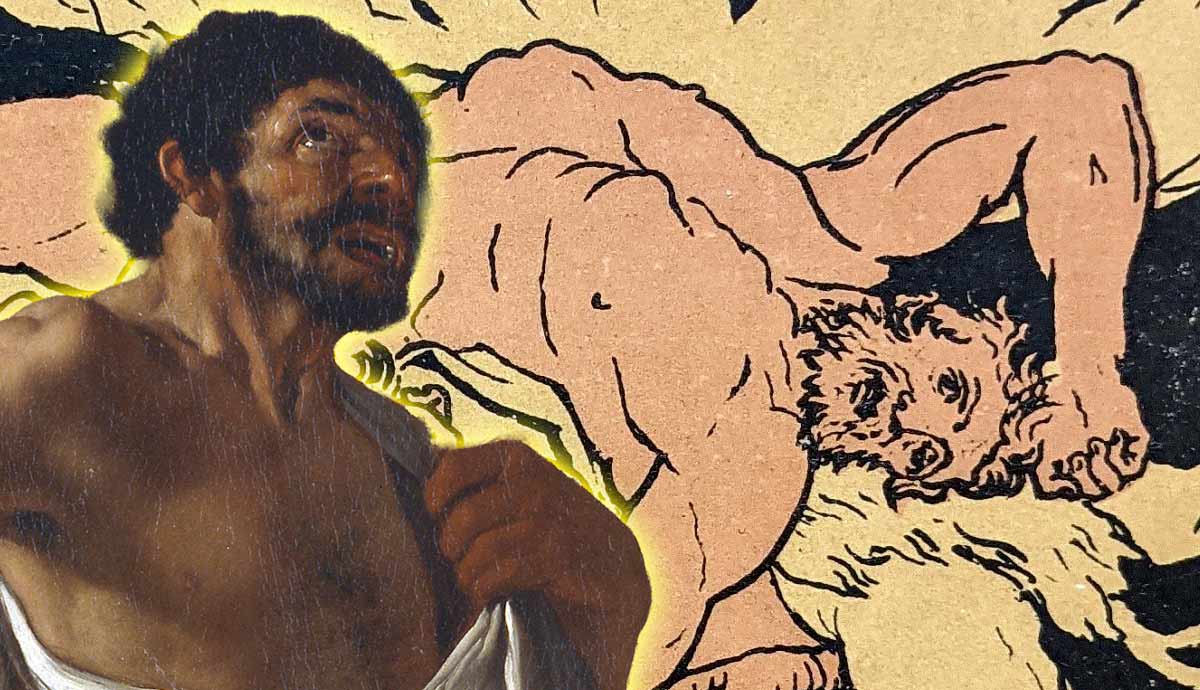

Sulpicia’s Birthday Poems

Sulpicia, an aristocratic female poet in the 1st century BCE, mentions her birthday several times in the poems attributed to her. The first time, she complains that her uncle Messalla has planned to take her to the countryside to celebrate, which unfortunately means she will not be able to see her lover Cerinthus. In another poem, the trip has been canceled, and she hopes that they will all be able to celebrate her birthday together. She also writes a poem for the birthday of Cerinthus, praying to his tutelary deity and Venus, the goddess of love, that he returns her affection. In another poem, she again speaks of her birthday, and of dressing herself in ritual robes to honor her tutelary deity and ask the goddess to guarantee their love.

While it is questionable whether these poems relate to real events or were invented to paint a picture of a love story, they indicate that birthdays were important. They also show that sacrifices were commonly made to the tutelary deity of the birthday boy, his Genius, or girl, her Juno, by the birthday boy or girl themselves, and sometimes also by others; more on this below. They also indicate that some kind of celebration, whether that be a trip away or a party, was customary.

Birthday Parties and Gifts

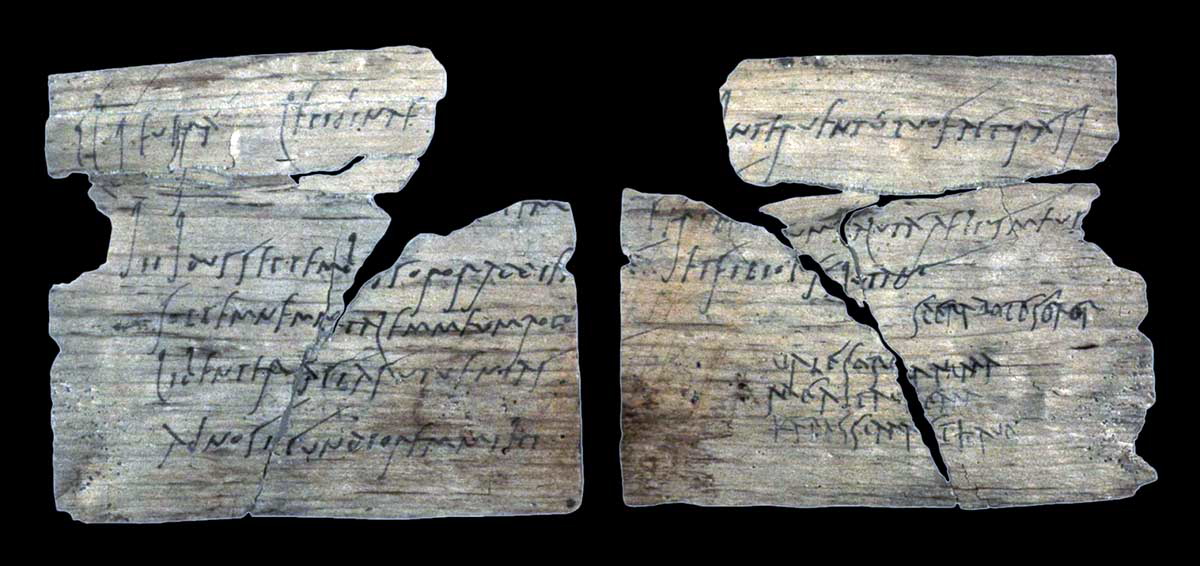

The Vindolanda tablets, some of the oldest surviving written documents from Britain, are records of military matters and personal messages from the Roman garrison at Vindolanda. They include an invitation from one woman living in the camp, Claudia Severa, inviting her friend, Sulpicia Lepida, to attend her birthday celebrations at her home.

There are numerous other references to Romans marking the birthdays of their nearest and dearest, attending parties, giving gifts, and honoring the tutelary gods. Tibullus, an equestrian writing in the 1st century BCE, notes that he celebrated the birthday of his literary patron Messalla, for whom he wrote a poem as a gift (Tibullus, Elegiae 1.7). The poet Horace, also writing in the 1st century BCE, mentions the birthday of his patron Maecenas. He also composed a poem as a gift, describing Maecenas’ birthday as being as important to him as his own. Interestingly, he mentions a blood sacrifice.

“… the house gleams with silver: the altar is wreathed

with pure vervain, and waits to be stained with blood,

a sacrificed lamb:

All hands are scurrying: here and there, a crowd

of boys and girls are running, and see the flames

are flickering, sending the sooty smoke rolling

high up in the air.

And so that you know to what happiness you’re

invited, it’s the Ides that are the reason,

they’re the days that divide the month of April,

of sea-born Venus,

it’s truly a solemn day for me, and more

sacred to me almost than my own birthday,

because from that morning Maecenas reckons

the flow of his years.” (Horace, Carmina 4.11).

Blood sacrifices are not usually mentioned in descriptions of birthday rites. But Maecenas’ rites do seem to have been particularly elaborate, probably because he was an extremely wealthy and important aristocrat with close ties to the emperor Augustus. Other wealthy men, especially those running for office, are known to have marked their birthdays with public benefactions, such as paying the fees for all visitors to a bathhouse on their birthday.

Writing under Domitian in the 1st century CE, Martial wrote a poem on the birthday of his patron, Restitutus, and tells his patron that the epigram itself is Martial’s gift to him (Martial, Epigrams 10.87). Around the same time, in a letter to his wife’s grandfather, the senator Pliny the Younger tells the old man that he feels obliged to celebrate his birthday as if it were his own because his enjoyment in life depends on him (Pliny, Letter 6.30). The Emperor Augustus sent a letter to his grandson Gaius Caesar on the occasion of his birthday to express his sadness that the two could not celebrate the day together (Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 15.7).

Poems were not the only things given as gifts. The Roman playwright Terence, living in the 2nd century BCE, complains that one family had become especially extravagant in the gifts they expected for an upcoming wedding. His characters speculate that when the marriage produces a son, they will expect similarly extravagant gifts on their baby’s first birthday (Terence, Phormio, 1.1).

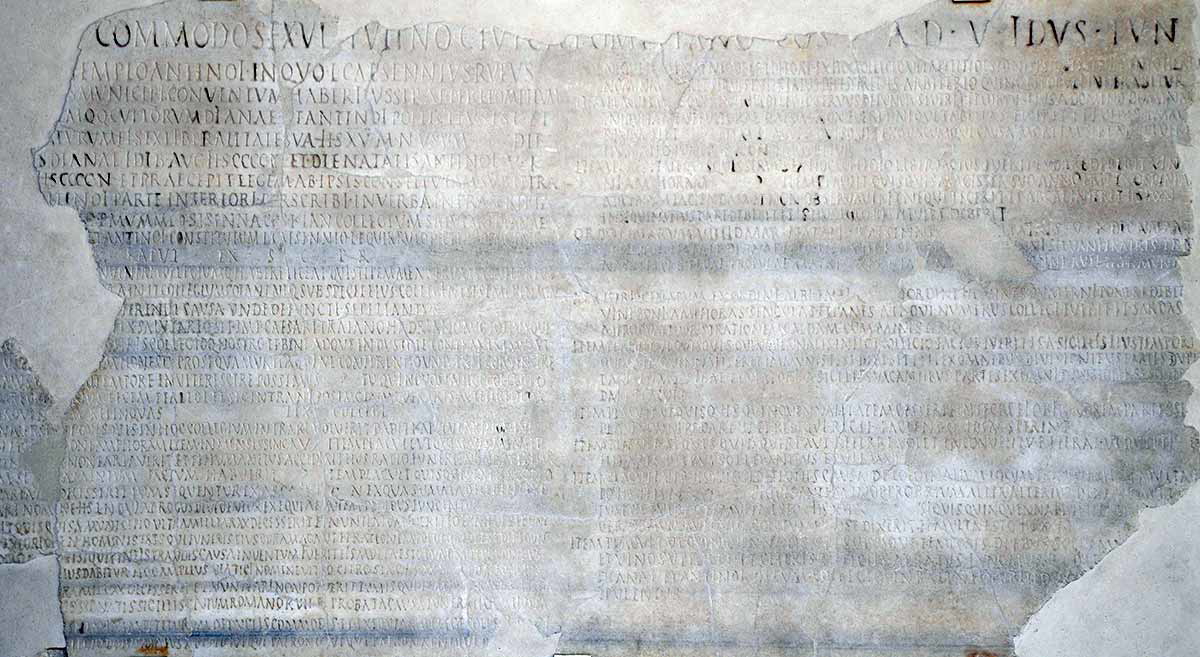

In addition to friends and family, a man’s dependents, including his slaves, freedmen, and clients, also appear to have been obliged to mark the birthday of their patron to show their gratia (gratitude) for the beneficia (favors) that they receive. This is preserved in many dedicatory inscriptions from throughout Italy erected by dependents, especially freedmen, to their patron. There are also inscriptions recording the establishment of endowments to enable dependents to celebrate the birthdays of their benefactors. A typical example comes from Ariminum in Italy. There, a certain C. Faesellius donated a sum of money so that his dependents could celebrate his birthday each year (CIL 11.379).

Sacrifices to the Genius and Juno

As mentioned, the sacrifices that someone made on their birthday were made to their personal tutelary deity, called a Genius for men and a Juno for women, usually asking them to protect the birthday boy or girl and bring them good fortune. The sacrifices are usually described as incense, libations, and oak cakes, though Horace suggests that Maecenas’ Genius received the blood sacrifice of a lamb. In the Roman state religion, a bull was the usual sacrifice to the Genius of the emperor, but a lamb may have been a more economical alternative.

The Genius and Juno were personalized deities attached to every person, entity, and location from birth. The 3rd-century grammarian Censorinus is the only surviving Roman author to explicitly explain the concept of a Genius:

“A Genius is a god under whose protection each person lives from birth… It is believed that our Genius has the greatest, or rather absolute, power over us… Therefore, we offer special sacrifices to our Genius every year throughout our lives. Although it is not the only god, but one of the many gods who support human life during everyone’s allotted span… all these other gods show the effect of their divine powers at only certain points for each person and therefore are not summoned with annual religious observances during the entire course of one’s life. Our Genius, on the other hand, has been appointed to be so constant a watcher over us that he never goes away from us for even a second, but is our companion from the moment we are taken from our mother’s womb to the last day of our life.” (Censorinus, De Die Natali 3.1-5)

Individuals cultivated their own Genius on their natalis, the anniversary of the start of the relationship between a man and his deity. The Genius of the paterfamilias of a domus, comprising his kin and familia (slaves and freedmen), was given a prominent place in the household shrine. It was typically depicted in the domestic lararium dressed in a toga drawn over its head (capite velato), holding a patera and a cornucopia. Dedicatory inscriptions from throughout Italy demonstrate that it was common practice for members of a familia, in particular freedmen, to honor the Genius of their paterfamilias.

Ovid’s Melancholy Birthdays

Ovid, a Roman poet during the reign of Augustus, wrote his Tristia (Sad Things) between 8 and 12 CE, when he was exiled from Rome and sent to Tomis (present-day Romania). This was decreed by the emperor, but the reasons are uncertain. On his birthday, he says that his Genius has followed him into exile and expects the same rites on his birthday, despite his sad state:

“I suppose you expect the usual kind of honors,

a white robe hanging from my shoulders,

a smoking altar circled by garlands,

grains of incense crackling in the flames,

myself to offer cakes to mark my birthday,

and make propitious prayers with fine words?” (Ovid, Tristia 3.13)

Ovid explains that he would rather light his funeral pyre covered with deadly cypress on this day because he finds the gods unresponsive to his plight. He also describes himself making the birthday of his wife, who is back in Rome:

“… and let me wear the clothes I wear only once a year,

of shining white, so different in color to my fate:

let them erect a green altar of grassy turf,

and veil the warm hearth with a woven garland,

Boy, give me incense that delivers a rich flame,

and wine that hisses, poured on the sacred fire.” (Ovid, Tristia 5.5).

Ovid asks the birthday spirits to protect his wife and ensure she enjoys a happier fate than his. While Ovid’s verses give a melancholy description of birthday rituals, they reflect the types of rituals undertaken for the Genius and Juno.

Birthday of the Emperor

When Rome transformed from a Republic to an Empire, the Romans were placed in the position of having a king, but one whom they refused to frame in the same terms as the kings of old, as the office had become taboo. Moreover, while the emperor was venerated as a god in other parts of the Empire, the Romans were careful not to treat him as a god. This, too, had become taboo when Julius Caesar accepted a divine statue—and therefore divine status—inside the temple of Venus Genetrix in Rome. After this, the emperor was only considered divine posthumously after undergoing apotheosis. Consequently, the Romans had to develop new ways to formulate the position of the emperor in Rome.

One approach was to recognize the emperor as the paterfamilias of the Roman state. Just as the paterfamilias represented the domus in all public dealings and ensured its prosperity, the emperor served the same function for Rome. He was thus called pater patriae, father of his country. As such, sacrifices could be made to the gods for the protection, health, and success of the emperor, treating him as the paterfamilias of the Roman state, approaching but never crossing those taboo lines.

We know quite a bit about how the imperial cult was conducted in Rome from the survival of the records of the Arval Brothers, an aristocratic priesthood established for the worship of the goddess Dea Dia, who also took on imperial cult rites under the Empire, probably mirroring the activities of many priesthoods. Conducting rites on the birthday of the emperor and some other members of the imperial family was core to their activities.

The annual records of the Arvals, known as the Acta Fratrum Arvalium, are fragmentary, but we can see that they regularly made sacrifices on the birthday of the emperor, to his Genius, but also to Rome’s Capitoline Triad, Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Juno Regina, and Minerva, for the health and prosperity of the emperor. Other gods, such as Divus Augustus, the deified Augustus, and Salus, the personification of health, also received sacrifices, but beyond the Capitoline Triad and Genius, the exact combination of gods changed over time.

We know from various other surviving calendars that, in addition to the emperor, the birthdays of other members of the imperial family, both living and deceased, were also celebrated. Under Augustus, his wife, Livia, and his grandsons, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, also had their birthdays celebrated. Under Tiberius, it was his adopted son Germanicus and his two sons. Under Caligula, his grandmother Antonia Minor and mother Agrippina were added, and his sister Drusilla after her death. Under Claudius, the birthdays of his wife, Messalina, and son, Britannicus, were marked. Messalina was later replaced by Claudius’ new wife and Nero’s mother, Agrippina the Younger, and under Nero, the birthday of his deceased biological father, Domitius Ahenobarbus, was also marked. Nero’s various wives and daughter, Claudia Augusta, probably also had their birthdays celebrated. Similar practices continued beyond the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

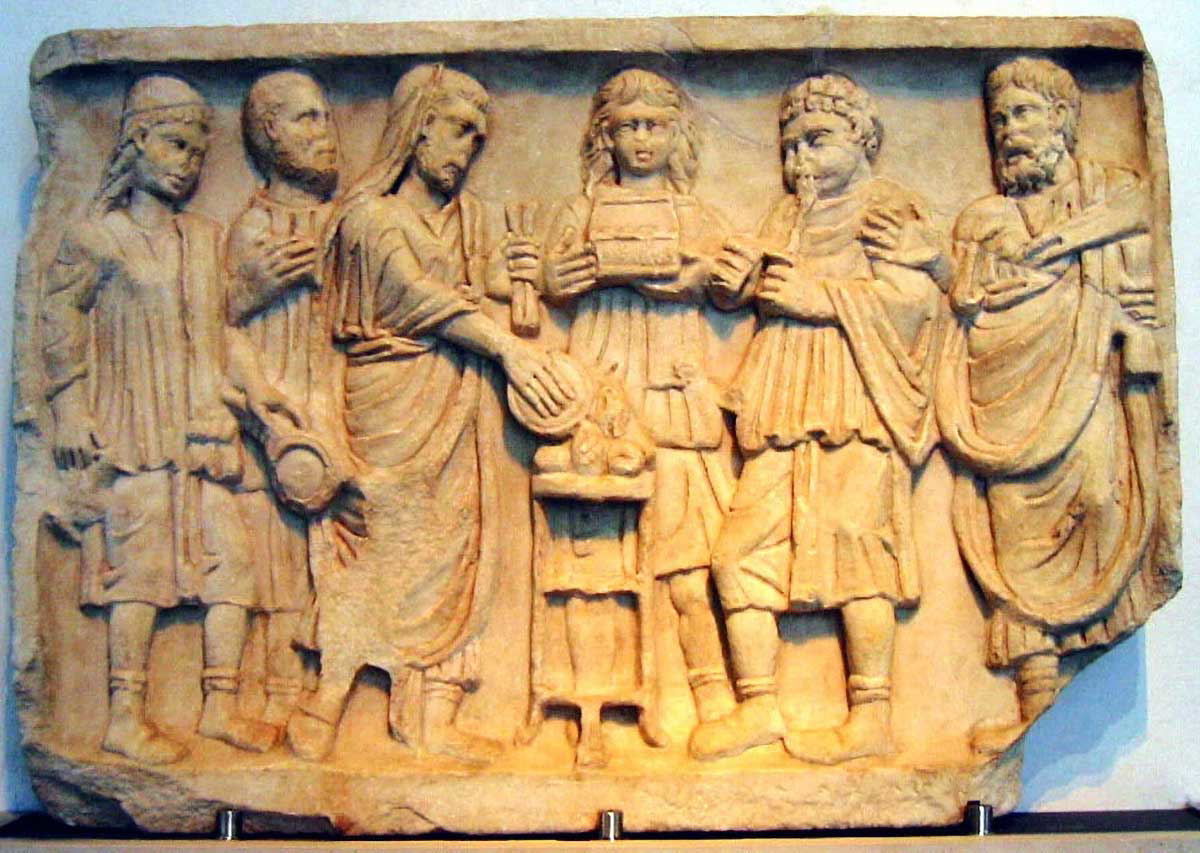

These state cult practices probably emerged following Augustus’ household cult becoming part of the state religion. We infer that the imperial household cult became public due to archaeological evidence such as the Frieze of the Vicomagistri. Probably dating to the reign of Tiberius, the grand scale of the frieze indicates that it shows a public procession. There are four priests in the procession carrying small statuettes, similar to those used in household shrines. Three of the statuettes are identifiable as a Genius and two Lares, with many similar statuettes surviving from shrines. The fourth statuette is no longer identifiable.

It is unclear whether the imperial household cult was made public by decree, perhaps when Augustus was awarded the title pater patriae in 2 BCE, or if it is something that just happened gradually, as many Romans decided that the birthday of the emperor was as important to them as their own.