Recent archaeological excavations of sites on Crete suggest that the ancient Minoans may have engaged in human sacrifice. While our inability to read the Minoan script, Linear A, makes it challenging to interpret this evidence, it is possible that these rituals were connected to the story of the Minotaur and the Minoan practice of bull leaping. This article looks at the evidence and the most prevalent theories among researchers.

Early Evidence for Human Sacrifice

In 1979, at the site of Anemospilia, Greek archaeologist Yannis Sakellarakis found evidence suggestive of human sacrifice. In a chamber he identified as a shrine or sanctuary, and human bones of a teenage male lying on an altar. His legs were bent backward to the thighs, indicating they had been tied up as if for a sacrificial ritual. The bones show discoloration, indicating rapid loss of blood, and a bronze knife was found in the bones, near the neck, possibly indicating his throat had been cut. Nearby were the bones of an older man, believed to be the one who carried out the sacrifice, and a woman, identified as a priestess, considering Minoan religion is believed to have centered on the sacred feminine.

Evidently, the ritual had been interrupted by a devastating earthquake. Sakellarakis believed the sacrifice was to a god as an act of appeasement to ward off impending doom. While he did not specify which deity, it could perhaps have been an early Minoan form of Poseidon, the god associated with the sea and earthquakes. Unfortunately, the ceremony was too late, as the victim and his executioners were all killed in the disaster. This scene occurred sometime around 1700 BCE, during the peak of Minoan palace culture.

At another site, the famed Palace of Minos at Knossos, Peter Warren, a prominent British archaeologist, discovered the remains of children. Aged eight and eleven, they had cut marks on their bones along the arms, legs, and collarbone, indicating they had been butchered. These same cut marks are typical in the bones of sacrificed animals, particularly those meant to be consumed after sacrifice. This led Warren to believe in the possibility that Minoans performed human sacrifice, but also engaged in cannibalism. These discoveries were made nearly 50 years ago, yet remain the strongest evidence for the theory that human sacrifice was part of Minoan ritual.

The Myth of the Minotaur

While we cannot decipher surviving Minoan texts to try to analyze this archaeological evidence, numerous Greek sources mention the Minoans (a modern term not used by the ancients), usually referred to as Eteocretans, or “true Cretans.”

According to the Greeks, Crete was the island nation ruled by King Minos, a son of Zeus. After Minos’s own son was killed in Athens, the king attacked the city and demanded tribute in the form of seven male youths and seven female maidens to be sent as a sacrifice to his pet, the monstrous Minotaur. Whether this sacrifice was demanded every year or every nine years depends on the version of the myth.

The Minotaur was depicted as a terrible half-man, half-bull creature. It was the offspring of Minos’s queen, Pasiphae, and the Cretan Bull, itself originally meant as a sacrifice to the gods. When Minos failed to sacrifice the bull, Poseidon cursed him, forcing his wife to lust after the bull. With the help of the genius architect, Daedalus, she managed to mate with the bull by climbing into a wooden cow. Soon after, the Minotaur, named Asterion, was born.

While the Minotaur was partly human, Minos kept him as a monster beneath his palace in a labyrinth, a complex maze of passageways, to be fed human victims. After the hero Theseus volunteered as a sacrifice, he managed to kill the Minotaur with the help of the princess, Ariadne. She gave Theseus a sword and a ball of thread to help him find his way out of the labyrinth. Thus, Minos was overthrown, and the Greeks later conquered the Eteocretans.

Minoan Bull Leaping

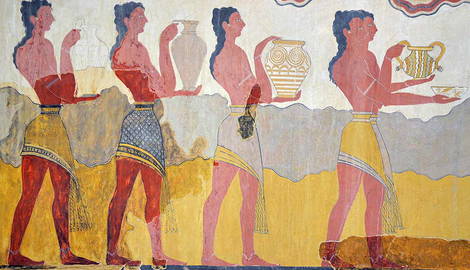

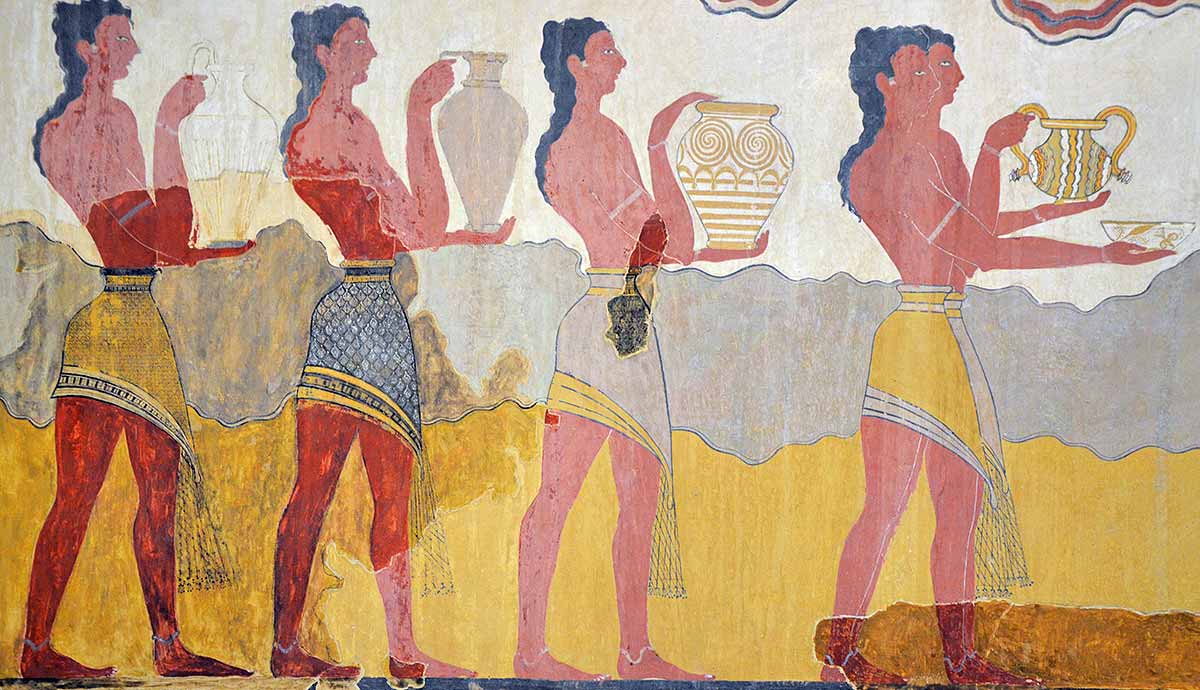

While the story is considered a myth, some archaeologists find parallels between demanding youths to sacrifice to a bull figure and the famed bull-leaping figures found throughout Minoan art. It is believed that both male youths (represented as red to reflect their darker skin) and female maidens (represented in white, with lighter skin) engaged in this dangerous pastime.

The Hagia Triada sarcophagus may depict a bull sacrifice. It includes painted scenes of priestesses in white and a male double-flute player in red. On the far right are the horns of consecration, a religious symbol that seems to represent bull horns and is often associated with shrines or places for religious rituals. The other side depicts people bringing offerings to a deceased individual, presumably the person for whom the sarcophagus was made. Human remains were found inside the sarcophagus, and it is assumed he was of a high status. Was the bull depicted in the scene an offering to this person in death?

Bulls were important symbols in most ancient cultures. For the Greeks, bulls were associated with both Zeus and Poseidon, and the hecatomb (sacrifice of 100 oxen) marked the start of the Olympic Games. Bulls reflected power, strength, and sacrifice.

A Grizzly Ritual?

Iconographic evidence makes it clear that bulls played a role in Minoan religion, but the specifics are unknown. Numerous theories have been suggested to explain the evidence. While there is no direct evidence, a fanciful theory suggests that some Minoan religious ceremonies, perhaps important funerary ceremonies, involved bull-leaping. If the youths survived the dangerous athletic display, perhaps the bull was sacrificed. If they died or otherwise failed in the bull leaping, the youth may have been sacrificed or butchered as an offering for the deceased. Evidence of butchering suggests that they may also have been eaten, as is the case with other types of sacrificial animals.

If the Minoans did demand an athletic contest with a bull, and then eat the youths, does this reflect the myth of the Minotaur? While bulls are herbivorous, perhaps the Minoans invented the story of a “man-eating bull” to coincide with their rituals and cannibalistic behavior. The Athenians could have discovered this fact and invented the notion that they were subjected to this treatment, though no evidence exists of Minoans ruling Athens at any point.

A later story from Greek mythology claims that Zeus, disgusted by humans consuming their young, destroyed an ancient civilization by flooding it. This could be explained by the eruption of Thera, a volcanic island 75 miles north of Crete, which exploded around 1500 BCE. This eruption could have triggered earthquakes, and thus tsunamis, that crashed into the island and destroyed the settlements.

The hypothesis above is fascinating, but purely speculative. While archaeological excavations indicate Thera’s eruption affected Minoan settlements, the evidence shows earthquakes and fire did the damage, not floods.

The Debate

Not all historians accept the idea that the Minoans regularly engaged in human sacrifice. Dennis Hughes has disputed the interpretation of the Anemospilia evidence, suggesting that the remains and iconography are not suggestive of a shrine and altar, that the bronze knife is a spearhead, and that there is no clear evidence that the body was bound. He argues that the human sacrifice interpretation is a matter of wanting the evidence to fit the theory.

However, the majority of contemporary archaeologists suggest the evidence is sufficient. Peter Warren and Rodney Castleden, both well-respected Minoan experts, support the theory of human sacrifice. Maria Vlazaki-Andreadaki, excavator at the site of Kydonia in Crete, claimed she found more evidence during her digs, and that as historians, we “cannot avoid mentioning human sacrifice in Minoan Crete.”

She discovered the remains of the skull of a young girl, who had been systematically dismembered by a sharp weapon, probably a dagger or sword, and placed along with animal bones in a ceremonial courtyard. The other remains consisted of dozens of sheep, goats, pigs, and oxen. The remains had been deliberately covered, possibly to stop them from being consumed by wild animals. The sacrifice occurred during an earthquake, similar to the find at Anemospilia. Vlazaki-Andreadaki believed the sacrifice was to a chthonic deity, to appease them during this earthquake.

There is also evidence of occasional human sacrifice among later Greeks. Homer and other poets frequently discuss it, though that is relegated to the realm of myth and poetry. Yet the historian Plutarch also mentions instances, and archaeology supports it. Mt. Lykaion, a sanctuary dedicated to Zeus in Arcadia, was long rumored to have rituals including human sacrifice. In 2016, skeletal remains were discovered in the temenos, or sacred precinct, and their layout was not typical of a burial. Myths tell the story of Lycaon sacrificing his son and feeding him to Zeus. He was turned into a wolf as punishment.

The Reality

Historians are divided over human sacrifice in Minoan Crete, but the majority argue that there is evidence supporting this theory. The question remains whether it was a common or even acceptable practice, or something exceptional, conducted in rare circumstances. Greek myth is full of stories in which Zeus forbids the practice, yet it occurs nonetheless. Perhaps it was only in dire circumstances, such as the earthquakes mentioned above.

However, these myths are written from the Greeks’ perspective. How can we analyze the Minoans’ viewpoint? Until records are deciphered, we can only guess at the frequency, reasoning, and rationale. The remains seem to point towards the sacrifice of children or young people, but that physical evidence is scant, indicating it was not a common practice. Whether human sacrifice had any connection to bulls, cannibalism, or the myth of the Minotaur remains a fascinating question, but one that is impossible to answer.