The term “Scholasticism” refers to the philosophical method practiced at the “schools” or universities during the Middle Ages (hence the name Scholasticism). The word is a broad umbrella term for a kind of philosophical practice dominant during the Middle Ages in Europe. This means that several philosophers can arguably be placed into this category, despite important differences among them. This article will review five of the most important examples from the history of philosophy: Anselm of Canterbury, Peter Abelard, Duns Scotus, William of Ockham, and Thomas Aquinas.

What Is the Scholastic Method?

To understand the Scholastic method, we must consider its historical context. While the first “western university” dates to Plato’s Academy, the modern-day institution we understand as the university arose in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. These are the “schools” where the Scholastic method became a dominant form of doing philosophy. The emphasis here is on “method” because it was not considered to be a “tradition” in the same way as other philosophical movements. There is, in fact, much controversy over many so-called “traditions” or “movements” in philosophy, but suffice it to say for our purposes here, the most dominant and common characteristic of what we call “Scholasticism” was its method.

The method of the Scholastic philosophers focused largely on logical structure. Upon the rediscovery of Ancient Greek philosophy, there was a revival of “dialectics,” first defined as “the art of conversation,” but which developed into a rigorous set of techniques for critical reasoning. This emphasis was generally shared among those categorized as “Scholastic philosophers.” They also explored many similar topics, especially subjects relating directly to Christianity. This is why many of the philosophers from this period derive from certain monastic orders, another key parallel development of the time. Aquinas, for example, was of the Dominican order, and Scotus and Ockham were of the Franciscan order. However, there were also important differences stemming from some key debates of the time.

One such dispute was the argument between realists about universals and nominalists. At one end was “extreme realism,” which advocated that individual objects are real insofar as they participate in the universal. At the other extreme was “nominalism,” which is the position that there is no such thing as universals, they are just names we give to things to try to organize them. As we will see, a clear example of this position was Ockham. In between was “moderate realism,” which presented a compromise by promoting that universals are real, but they are not independent of the particular things in the world. A clear example of this middle-road position was Aquinas. But again, what they did generally share was a particular method of doing philosophy that emphasized critical thinking.

1. Anselm of Canterbury

Two of the philosophers in this list of five were so influential as philosophers and theologians that they were canonized: Saint Anselm of Canterbury and Saint Thomas Aquinas. As with most of the philosophers of the medieval period, Anselm largely took up Christian topics.

Of these religious topics, central was the existence of God. Applying the Scholastic method of logical reasoning, many of these medieval philosophers presented arguments trying to prove God’s existence. Of all of Anselm’s work, this is where his fame primarily resides. His argument for this, known as the “ontological argument,” is found in his book the Proslogion. In this argument, Anselm logically works from the definition of God to conclude his necessary existence.

Everyone, argued Anselm, whether they believe or not, whether they are a “fool” or not, has the idea of God as “the greatest conceivable being.” Starting with this agreed-upon definition, Anselm works through this proof logically, which in sum is as follows: the greatest conceivable being, by such a definition, must necessarily exist, otherwise this being would not be the “greatest conceivable being.” His position, which has fascinated readers ever since, is not free of critiques, most centrally that he is making an unjustified leap from definition and idea to necessary physical existence.

2. Peter Abelard

Peter Abelard is perhaps equally famous for his work as for his biography. His is a love story for the ages, which involved a secret love affair with a young woman, Héloise, an angry uncle, and a castration. The pair were forced to end their relationship, both retiring to the cloisters. But his philosophical work did not end there. Abelard is best known for two of his works Know Thyself and Sic et Non.

The former is an ethical treatise which explores Abelard’s moral philosophy on non-consequentialism, or the intentions as most important in judgments. This position was not without critique either; as is often the case with Medieval philosophers, charges of heresy were frequent. Here one such charge was that this “excused” Christ’s executioners since they had “intentions they thought were right.”

The latter text is especially representative of the Scholastic method, as it explores the for and against of 158 different questions. He did not generally end with a conclusion but rather he presented the different sides of answers to the questions. But even this was attacked by some, very poignantly Bernard of Clairvaux for instance, arguing that logic simply cannot be used to tackle theological inquiries.

3. Duns Scotus

Duns Scotus is unique in this list for being the philosopher we know the least about biographically (his birth year is not known with certainty, and he probably died around 1308). This complicates our understanding of his work because, while many writings have survived, piecing them together has been a challenge—not to mention Scotus is not an easy read.

Again, as with many medieval philosophers, one of his aims was to prove the existence of God philosophically. Despite the dominance of Aristotelian thinking in his time, in many key ways, he departs from this. One such important departure is regarding attributes of God such as omniscience and omnipotence, which Scotus argues can only be known via revelation, not natural reasoning as Aquinas argued. Scotus moved away from too much dependence on the philosophical system of Aristotle. Aristotle, like many other philosophers, had emphasized the goal of life to involve philosophical reflection and contemplation, whereas Scotus placed above this the objective of a blessed union with God—each of us has a sovereign will to aim toward this.

Scotus also diverged from Aristotelian thinking regarding form and matter. Aristotle had argued that two individuals were differentiated by their matter, whereas Scotus would diverge in the belief that there was rather a more fundamental uniqueness that distinguished two people. Scotus wanted to maintain a balance between a universalizing factor and an individualizing factor, altering slightly the dominant Aristotelian view but without collapsing into Platonism.

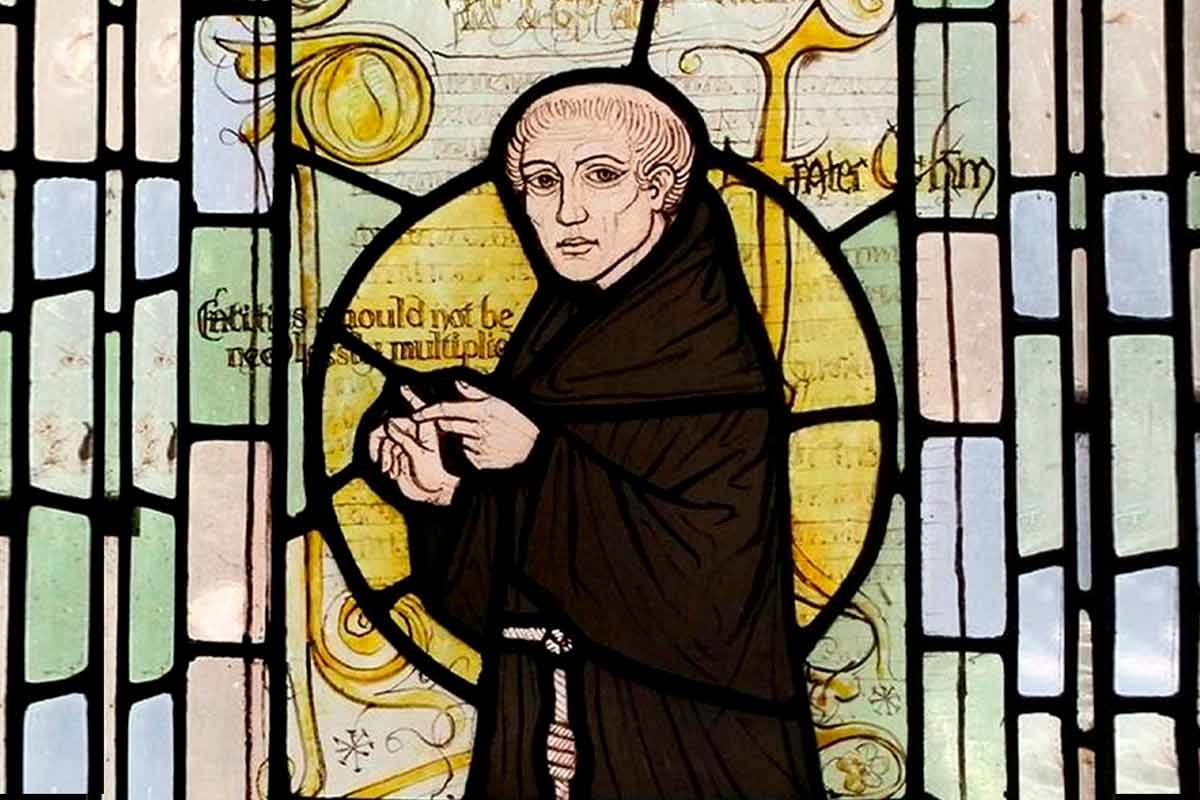

4. William of Ockham

Scotus had spent time studying in Oxford in the 1280s, and the next medieval philosopher under review, William of Ockham (born in the late 1280s and died 1349 from the plague) did as well, arriving not long after Scotus left. As Scotus diverged from Aristotle, Ockham diverged from Scotus. Ockham was what is called a “nominalist” (or what might be even better termed a “conceptualist” given his emphasis on the role of “concepts”) which refers to the position that there are no universals, just the names that we give to things in our minds. He called these “signs” and distinguished between “natural” and “conventional” signs. The former refers to the thoughts in our minds and the latter refers to the terms used to express those thoughts in the mind. All the resulting concepts from our minds lead to languages.

Ockham also contributed to the history of political philosophy. He denounced certain activities of the Pope and he outlined what in some ways resembles an early social contract theory. He argued that rulers derive their power and authority from their subjects. Subjects have a natural right to choose their leader. But neither did this mean he rejected Papal authority; rather, this was considered more constitutional-like, and not absolute. The Pope still retains divine authority, nonetheless, in his view.

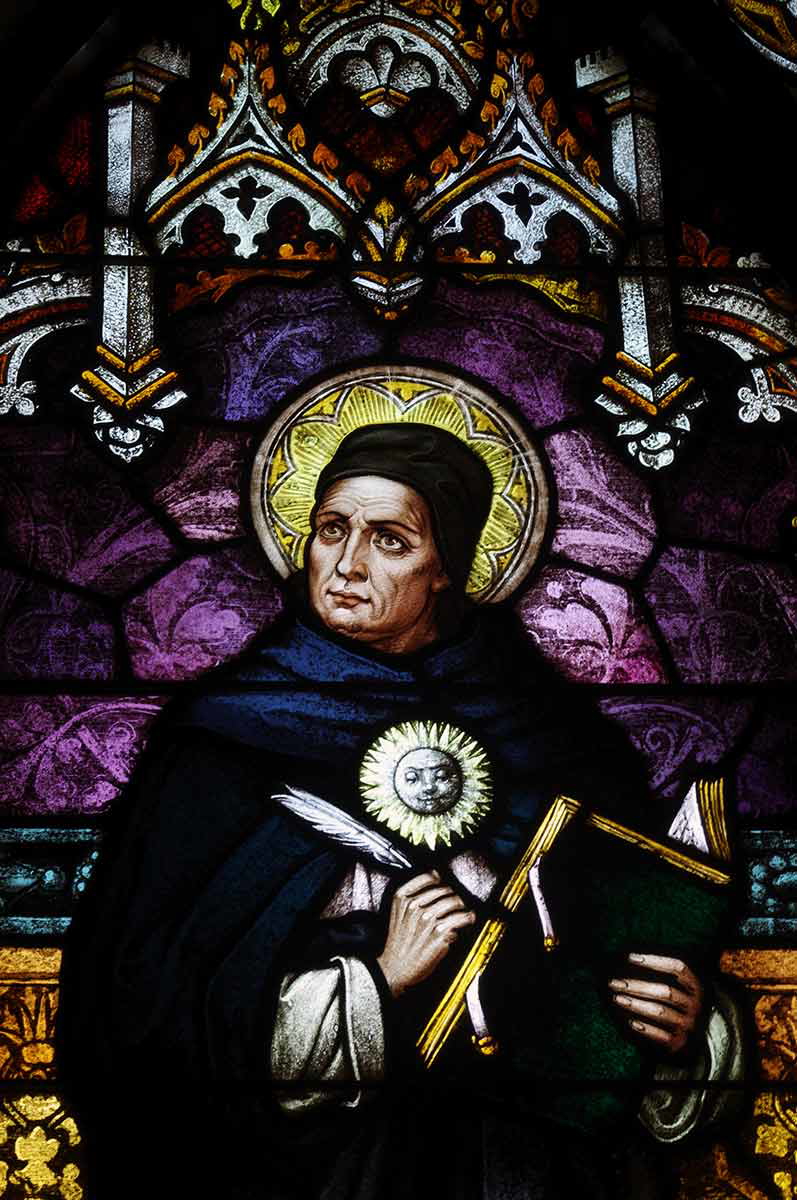

5. Thomas Aquinas

Aquinas has been placed last here as he is probably the most influential of all the philosophers from the medieval period—“Thomism” remains the official philosophy of the Catholic Church. Despite his renown now, it was not achieved during his lifetime. He was even canonized in 1323 but still was not fully appreciated until the 16th century and then again in the 19th and 20th centuries.

With Aquinas we have a return to the dominance of Aristotelian thought. Aquinas, in many ways, became the quintessential “Scholastic philosopher” with his rigorous use of logic to examine, dissect, and organize big questions and their proposed answers, such as the existence of God. His process was also a dialectical one in which he presented all sides of an issue but went a bit further than Abelard in proposing plausible conclusions. And even in cases where something was disproven, he worked to give it merit nonetheless, in some cases supporting that it contained nuggets of truth or at least helped work toward a clearer conclusion.

Aquinas was quite a voracious writer and popular lecturer. One of his most important works was the Summa theologica where he worked step-by-step to prove God’s existence, in Aristotelian form, from the evidence in the world around us, not just from faith. The proof of God’s existence is found in what he calls the “five ways,” and each of those ways is observable in the world around us. Thus, the basic structure found in all these ways follows the modus ponens structure of logic: if the world has feature P, then God must exist. And in each way, he confirms the existence of P to thereby confirm that God exists. In sum, Aquinas’s work is known as the “cosmological argument” because it uses data from the “cosmos” to prove God’s existence.

For instance, in his first way, or proof, he notes that there must be something that causes motion in the world that by itself does not need something else to cause it to have motion—this is not unlike Aristotle’s “unmoved mover.” So, if there is motion in the world, then there must be a God. There is motion in the world. Therefore, there is a God. But he is not without critiques either, some charging, for example, that these five proofs do not lead to one God, though Aquinas counters that they do.

These are all of course very brief summaries of important and complex philosophers. However, one summarizing conclusion to this overview that serves as a final quandary to consider is whether these philosophers, who shared an interest in thinking philosophically about theological questions, were especially fruitful in illuminating and explaining specifically how we think about God’s existence.