During the Crusades, warriors devoted themselves to protecting the Holy Land from attack, dedicating themselves to God, the Church, and their mission. Several orders of devout knights emerged, the most famous of which was the Knights Templar, but another well-known order was the Knights Hospitallers. They had one of the longest and most eventful tenures of any militant holy order. Starting as a small group of caretakers for sick pilgrims, they grew into one of the most powerful organizations in Christendom. Their centuries of service have left a lasting impact on history.

Humble Origins

The Hospitallers have a long history, beginning even before the European leaders considered the idea of a crusade to retake the Holy Land. In 1080, perhaps even earlier, a group of merchants from Amalfi, Italy, began tending to the sick and injured at a hospital in Jerusalem. They would soon be organized under the Benedictine order of monks. After the First Crusade successfully captured Jerusalem in 1099, the burgeoning order intensified its work. They set up hospitals in Italy and Southern France, seeing to it the needs of pilgrims moving to and from the Holy Land. Though their main concern was Christian travelers, they would also tend to non-Christians.

In 1113, this informal order was granted official status by Pope Paschal II. Its first leader, the Blessed Gerard, was named the first master, and its members were officially recognized as monks. During the rule of his successor, Raymond de Puy, the monks became more militant. In addition to providing medical attention and shelter for traveling pilgrims, the order began to hire mercenaries, knights, and other fighting men to protect the travelers from attack while on the road. Eventually, these warriors would become monks themselves, a transition that was possibly inspired by another order of warrior monks, the Knights Templar.

The order’s main base of operation was the hospital in Jerusalem, a large facility that could treat over 1,000 patients at a time. It was divided into men’s and women’s wings. The order took its name from this location, being officially named the Knights of the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem. This long name would be shortened to the Hospitallers, though they have also been known as the Knights of St. John, especially after Jerusalem was captured by Saladin in 1187 and they lost access to the hospital. Originally, they were named after St. John the Almsgiver, a 7th-century patriarch, though this was changed to the more well-known St. John the Baptist.

The Militant Order’s Organization

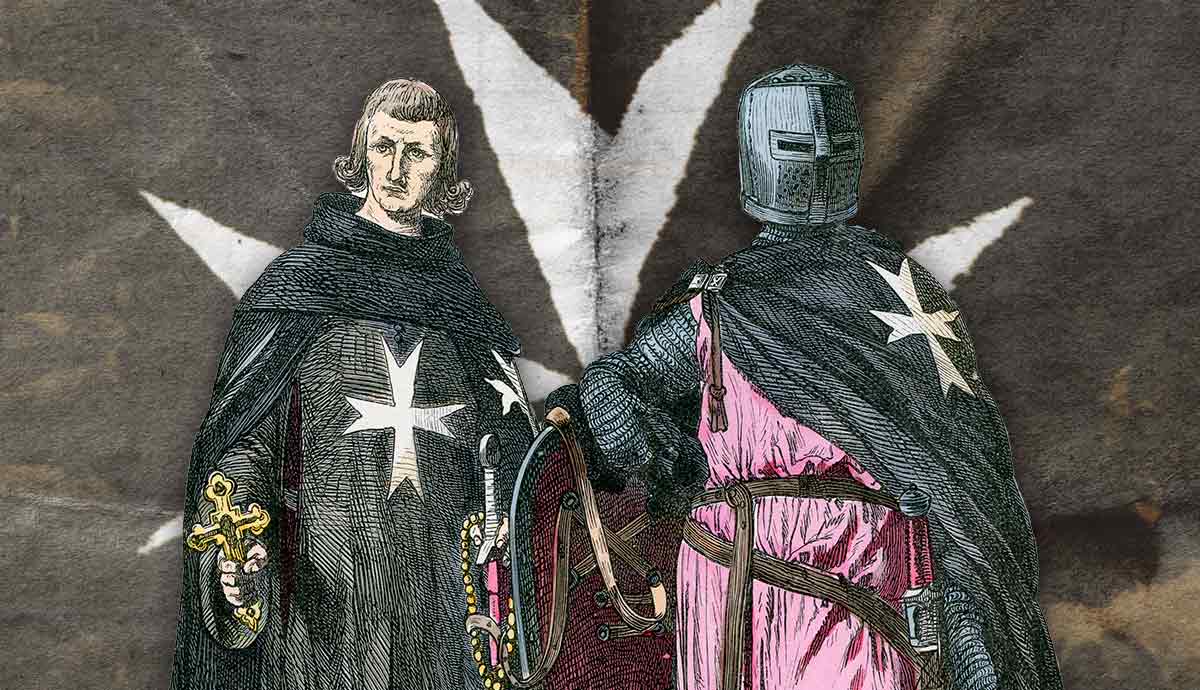

Like their brother organization, the Templars, the Hospitallers were a group of warrior monks. The group was structured using a combination of the monastic Benedictine and military hierarchies. At the head of the Hospitallers was their supreme leader, the Grand Master, who held this position for life. Directly under him was the Grand Commander, followed by the Master of the Hospital, who oversaw the day-to-day operations of the organization.

The bulk of the order was broken down into three broad sections. The most prominent were the brother knights. These men were of noble birth and, according to the medieval tradition, had been trained in the knightly arts of horseback riding and armed combat, both mounted and unmounted. These were the core of the Hospitallers, who the rest of the organization supported. Under them were the men-at-arms or serving brethren. These were commoners who did not have the same training as the knights, but they supported the knights in battle by acting as infantry. They would also act as blacksmiths, farriers, and general laborers who kept the order running. The third group was the clergy, who did not fight but oversaw the spiritual needs of the men, conducting religious services and fulfilling the Hospitallers’ original mission of caring for the sick and injured.

The Hospitallers were a monastic order, and the men who joined took vows of chastity, obedience, and poverty, vows which lasted for life. Once they joined, the members voluntarily subjected themselves to a lifetime of service to the Church as monks under the Benedictine rule, with some modifications to support their militant mission, such as prayers being replaced by military training. Though they expanded in size and influence, manpower was always in short supply, and the Hospitallers employed temporary members. These lay members did not take the vows of the full “professed” knights and did not have the same privileges within the order as full members.

The Hospitallers were cloaked in their own unique heraldry, a white eight-pointed cross or Latin cross on a black background. However, in the mid-13th century, this was changed to a red background, though the traditional black was still used occasionally.

Hospitallers in the Holy Land

Throughout the 12th century, the Hospitallers grew in size and influence, acquiring lands and territories in the Holy Land and Europe, which enabled them to continue their operations. With this vast network of holdings, recruits and wealth poured into the order, enabling them to expand their work. In addition to their hospitals and hostels to care for traveling pilgrims, the Hospitallers also acquired castles and fortifications, which emphasized their role as a fighting force. In 1144, they gained control over the strategically vital Krak de Chevaliers, granted to them by the Count of Tripoli. In total, about two dozen castles and fortresses were controlled by the Hospitallers in the Middle East, located mostly along trade routes and at seaports.

During the height of the crusades, the Hospitallers, along with their brother organization, the Knights Templar, were a formidable force. They plagued Saracen armies so much that the Muslim leader Saladin placed a bounty on them. They played a key role in several battles in the late 12th century, including the Battle of Hattin and the Siege of Jerusalem. After the fall of Jerusalem in 1187, the headquarters of the order was moved to Acre. However, out of respect for their work treating the sick, Saladin granted them a year to move the patients and infrastructure from the captured city.

The Hospitallers played a pivotal role in the Third Crusade, especially at the Battle of Arsuf. The Hospitallers made up the rear guard of the crusading army, which was continuously harassed by the Saracens. Frustrated by these repeated attacks, the Hospitallers launched a countercharge, followed by a general attack ordered by Richard the Lionheart. This battle was the only major field battle of the Third Crusade. They then participated in the capture of the city of Jaffa.

In spite of this success, Jerusalem was never recaptured, and the Hospitallers set to work providing protection and medical aid to the remaining Crusader holdings in the Holy Land. In 1271, the stronghold of Krak de Chevaliers fell to the Mamluks, marking the beginning of the end for their presence in the region. When the last Crusader stronghold of Acre fell in 1291, the Hospitallers aided in the final defense of the city and are credited with helping large numbers of refugees escape. Lacking any foothold in the Holy Land, they relocated to the island of Cyprus. When Cyprus proved unsuitable for their operations, they then shifted their sights to the island of Rhodes.

The Knights of Rhodes

Unfortunately for the Hospitallers, the island of Rhodes was controlled by the Byzantine Empire. In 1306, they began the conquest of the island, fighting against the Byzantines. They wrestled control of Rhodes and many other islands away from the Empire in 1309. From these bases of operation, the newly named Knights of Rhodes, or the Knights of St. John, shifted into a primarily naval force, battling Muslim pirates and naval forces. Around the same time, the Templars were dissolved, and many of their holdings were transferred to the Knights of St. John.

While on Rhodes, the Knights of St. John became an independent political entity, free from any other state, ruling the island as they saw fit. They set up their own administration and infrastructure, even minting their own coins, and the Catholic knights ruled over the primarily Orthodox population. Keeping with their original mission, they also set up hospitals in their new lands, tending to the sick and injured, and built churches and monasteries. Though they did concern themselves with civil matters, they were a militant order. Combat was still their primary mission. The next century saw the Knights of St. John holding their ground against continual Muslim expansion, particularly the Ottoman Empire and the Barbary corsairs.

From their base on Rhodes, they continually attacked Ottoman naval forces, acting as an anti-pirate force in the eastern Mediterranean. They also provided direct assistance to the Byzantines in their campaigns against the Ottomans on at least one occasion and launched multiple raids against targets along the North African coast. Their stubborn resistance left Rhodes and the other areas under their control as Christian bastions in an increasingly Ottoman Aegean Sea. By the mid-1400s, the Knights of St. John had a strength of over 450 knights and 2,000 other members. They held out against repeated attacks. The Ottomans struggled to remove the order, attacking Rhodes several times, first in 1455 and again in 1480. They were repelled both times. It would not be until 1522 when the knights were finally dislodged from Rhodes.

The Knights of Malta

After a brief time in Sicily, the order then found itself in possession of the island of Malta, being given the island by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. They were, for all practical purposes, an independent entity, though they were forced to pay the emperor a fee of a falcon every year on All Saint’s day. With this new land now under their control, the Knights of St. John once again set to work overseeing the administration and infrastructure of the island. Once again, they set up hospitals for the sick and created fortifications to protect against attack, as well as churches and chapels throughout the archipelago.

From this new location, the knights once again built up a fleet, attacking Ottoman and Barbary naval forces in the Mediterranean Sea. History repeated itself as the Ottomans tried to dislodge the knights from their island stronghold but failed to do so after a disastrous siege in 1565. In 1571, Ottoman naval power was broken at the Battle of Lepanto, in which a combined fleet of many Christian nations, including the Knights of St. John, won a decisive naval battle. Shortly after, the knights built their magnificent capitol at Valetta, named after the order’s grand master, Jean Parisot de la Valette.

As the 16th century wore on, they continued their mission of combating Islamic expansion and piracy in the Mediterranean, though they gradually began to lose their power and influence. The fervor that inspired their creation during the Crusades had faded, and much of Europe was more concerned with internal affairs, such as the Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Recruits and donations that had helped sustain the order diminished to a trickle.

While the Knights of St John continued to exist into the 18th century, it was clear that their organization was an outdated relic of a bygone age. They became less and less involved in military affairs, concerning themselves with the governance of Malta, until that was conquered by Napoleon in 1798. Though they lost control of the island, they continued to exist. The remnants of the once proud order established themselves in Rome, where it still exists today as a humanitarian organization devoted to international charity work, the reason for its founding in the 11th century.