The profound and instantly recognizable azure blue of lapis lazuli and its derivative pigment, ultramarine, has been, for millennia, an exemplar of wealth and power in the art world. Its name is derived from the Latin lapis, meaning stone, and lazulus, derived from the Persian word for blue. Mined, even today, in primitive and perilous conditions in the mountains of Afghanistan (although it can also be found in Chile and Siberia), this most prized of semi-precious stones has been, at times, deemed more valuable than gold.

Lapis Lazuli, the Most Perfect of All Colors

Used by the Ancient Egyptians as a conduit to the gods and immortality, lapis lazuli has seized the attention of viewers of art and art objects in works ranging from Giotto’s painting of the Scrovegni Chapel from 1303 to1305 to the elegant headdress of Vermeer’s 17th century Girl with a Pearl Earring. To have the wealth to commission an artist to use this symbolic pigment was a sure way to cement your status in the highest echelons of society. From the earliest offerings of amulets to the gods to the extravagant hand-painted Books of Hours of the 15th century, true blue (as it was often referred to in the Medieval period) has been used to illustrate devotion in religion and power in society.

From Earth to Heaven and Back Again

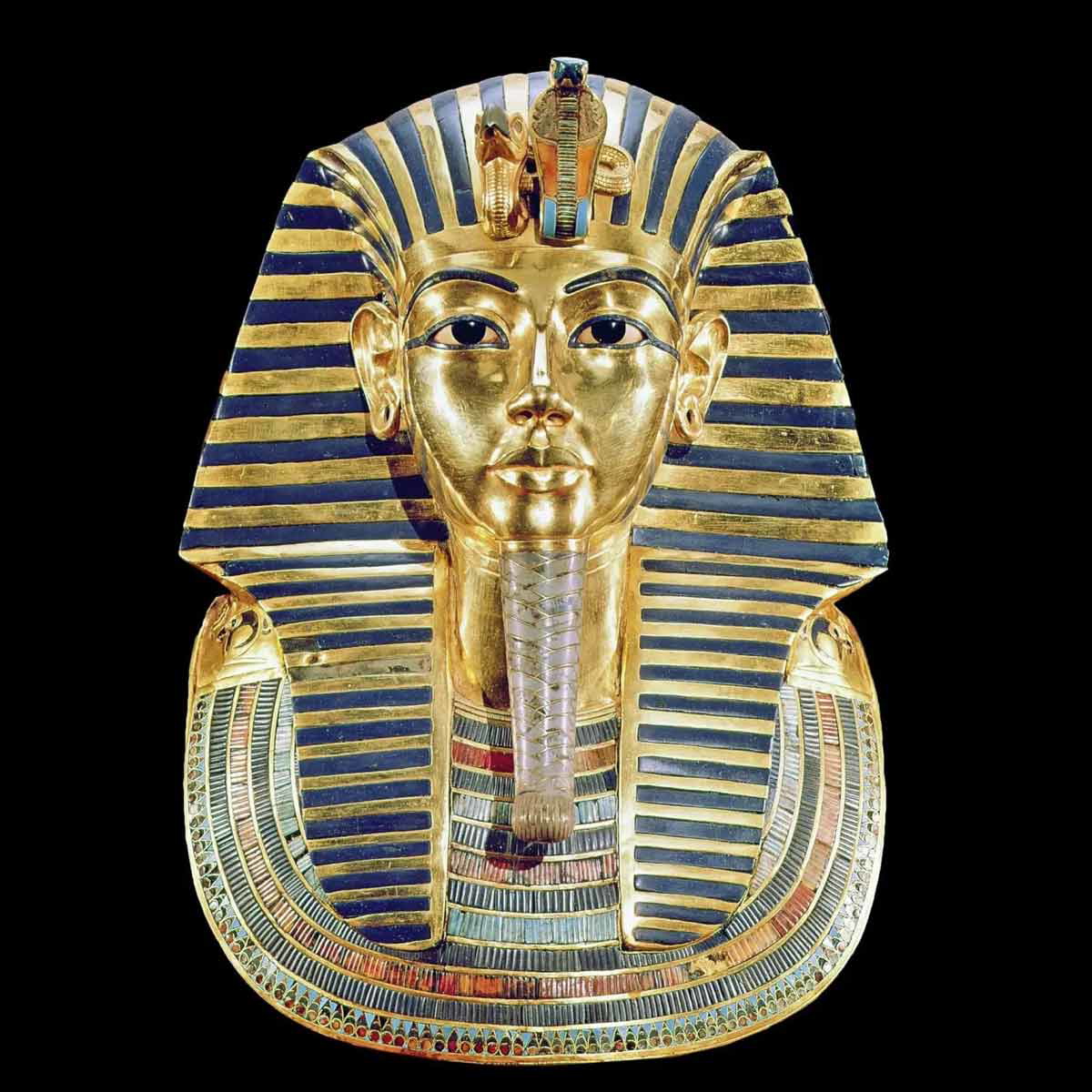

From the 7th millennium BCE, the Sar-i-Sang and Badakhshan mines were exploited to provide lapis lazuli, in a ground form, for use in cave paintings and decorative artifacts housed in Buddhist temples along the ancient trading routes of the Indus valley. Comprising the minerals lazurite, pyrite, and silicate, the stone became widely used across Asia and Europe. In Ancient Egypt, in its stone form, it was famously used for Tutankhamun’s funerary mask in the early 14th century. Thought to carry the soul onto immortality in the afterlife and combined with gold, lapis lazuli exemplified the eminence of the Pharaoh both on earth and beyond.

Although the Egyptians used lapis lazuli in its gemstone state in their jewelry and funerary adornments, they did not use the stone in pigment form. Instead, an alternative was created. Egyptian Blue, a copper calcium silicate, was developed in Ancient Egypt. Despite extensive modern-day research, it has been almost impossible to discover the method used to produce it, and its use has faded into the shadow of ultramarine.

From Stone to Pigment: The Advent of Ultramarine

Fine blue is derived from a stone and comes from

across the seas and so is called ultramarine. (Filarete, 1464)

Before the medieval period in Western Europe, blue was sparingly used in art, especially religious works. The most common colors used in devotional artworks were red, white, and black, even for painting the sea and sky. Blue was seen as the color of barbarism, an unfortunate association derived from reports of Pict and Celtic warriors tattooing their skin with blue pigments to create a striking appearance when facing their adversaries.

Although blue was widely extracted from plants such as woad, artists could not find a reliable and vibrant enough substance to provide them with a bright blue for painting and use in manuscripts. As trade routes developed and flourished across Asia and into Europe via the Silk Road, merchants discovered lapis lazuli, seeing examples of its use as a pigment in artwork, and brought it back to Venice, facilitating its dissemination throughout the continent.

By the 14th century, the use of Lapis in its pigment form of ultramarine had become widespread throughout Europe and Asia. In addition to the paintings of 11th to 17th century India and China, Western artists were harnessing the power of this vivid blue because of improved manufacturing techniques.

Cennino Cennini, in his 14th-century treatise Il Libro dell’ Arte described a lengthy fabrication process for ultramarine, which came into use around 1200, involving the incorporation of wax, resin, and various other ingredients being blended, ground, and washed numerous times before a satisfactory product emerged. It was this protracted process that resulted in the prohibitive cost of ultramarine for artists; although the stone itself was relatively inexpensive, it was time-consuming to refine. That did not stop artists from wanting to use it in their art. If anything, the costliness of ultramarine drove patrons keen to show off their wealth and demand its use in their commissions.

Virgin Blue

In the 12th century, Abbot Suger, an advisor to the courts of Louis VI and Louis VII and a writer on the arts and theology, developed the theory that color was light and that it permitted communion with the divine. It was Suger who, during his reconstruction of the Abbey of Saint-Denis near Paris, proposed the extensive use throughout the abbey of blue, in the form of gemstones and paint, as the color of the heavens. Combining it with gold, he used it to represent creation and paved the way for blue, particularly ultramarine, to become associated with the robes of the Virgin. As the cult of the Virgin grew, with almost every artist worth his salt offering paintings of The Annunciation or the Virgin in prayer, so did the use of ultramarine. From Abbott Sugar onwards, ultramarine became the Virgin Mary’s color.

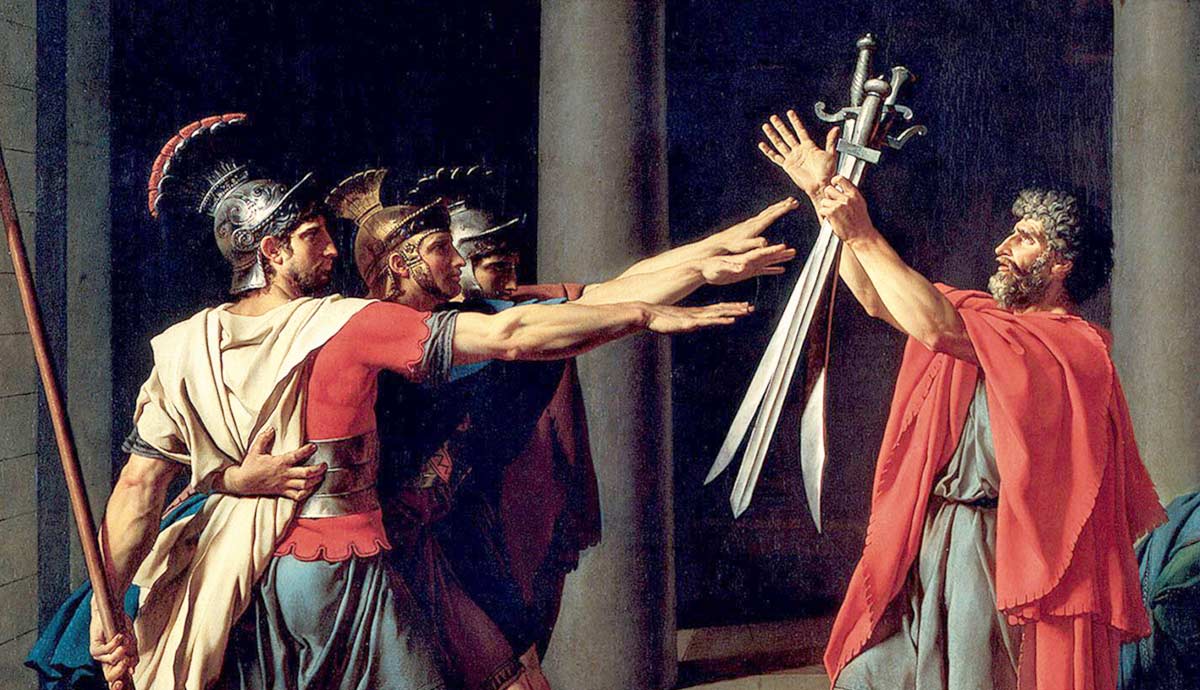

The Power of Blue

The use of lapis lazuli and ultramarine extended across Europe, and wealthy patrons of the arts began to see its use as a conspicuous display of their wealth. Amongst the patrons most able to afford such luxury were families such as the Medici and the Scrovegni, known for their commissioning of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. The cycle of murals painted by Giotto in the chapel marked the beginning of a trend for mural painting in fresco, which lasted for many decades.

With this appropriation of ultramarine in art and in conjunction with the flourishing cult of the Virgin, more paintings were commissioned throughout Renaissance Italy and France and further north into the Netherlands. Wealthy Netherlandish merchants and guilds did not hesitate to follow the lead of their Italian counterparts. Examples such as Rogier van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross vividly illustrate how ultramarine could be wielded as an expression of power and influence. It was commissioned by the Leuven Guild of Crossbowmen and hung initially in a chapel in the town primarily as a devotional offering to the Virgin but also as a reminder to the townspeople of the clout of the guild.

Ultramarine’s popularity persisted throughout the Renaissance in Europe despite the huge cost of its production. In the 16th century, lapis lazuli, in its raw state as a semi-precious stone, was used to create decorative objects commissioned by the same influential patrons. The Medici were particularly prominent in this respect. They had craftsmen like the Miseroni brothers and Bernardo Buonatalenti create pieces like the flask pictured above.

The Price of Luxury: Vermeer and Ultramarine

By the 17th century, ultramarine had become the go-to pigment for artists and patrons wanting to impress. As a painter of middle-class domestic interiors, Vermeer’s works might seem an unlikely vessel for the rich man’s pigment, but some of his best-known paintings are illuminated with flashes of blue, perhaps most memorably his Girl with a Pearl Earring. Vermeer’s love for ultramarine and its light-reflecting qualities meant that he used it not only in swathes of fabric but as a highlight in glass, white drapery, and foliage. His exuberant desire for the pigment eventually resulted in his financial ruin.

The New Blue: The Advent of Synthetic Ultramarine

By the 19th century, the obsession with ultramarine in painting showed no sign of slowing down. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s extensive use of the color in the illustrious Oxford Union murals illustrated its persistent allure. However, not all artists could afford to use such an expensive pigment to the same degree.

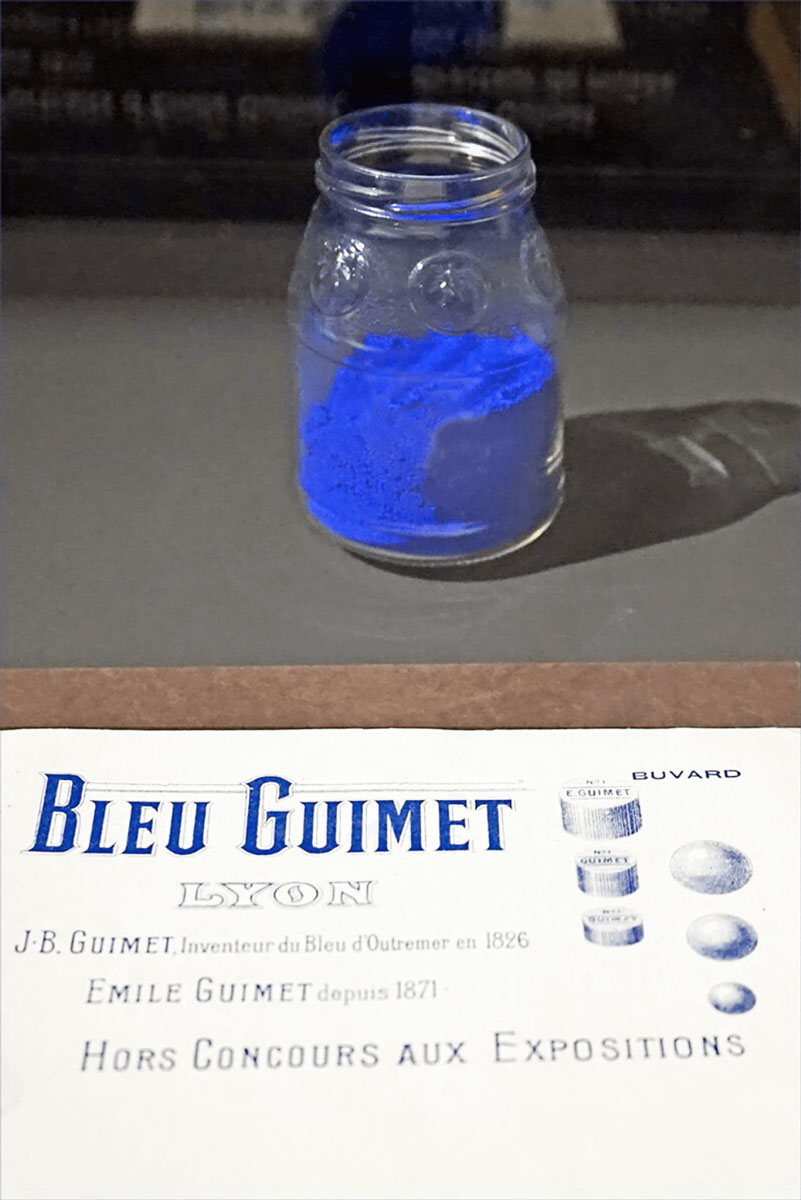

In 1824, ultramarine’s status in the art world had risen to such lofty heights that, to overcome the issue of the expense of using it in painting, the Société d’encouragement in Paris launched a contest with a prize of 6,000 francs to be awarded to whoever could develop a synthetic ultramarine pigment. Guimet, a French chemist, and German professor Gmelin were the frontrunners.

Gmelin claimed that he had developed his ideas the year before the contest but had decided to delay the presentation of his findings to the wider world. Guimet said that his work had been completed two years before. The committee stood in judgment and eventually awarded the prize to Guimet, much to the horror of the German contingent. As a result, the new synthetic color became known as French ultramarine. Despite this great leap forward in the production of the color, critics claimed that the manmade pigment lacked depth and appeared one-dimensional when compared with ultramarine created from lapis lazuli. And so the search for a worthy substitute continued.

From Opulence to the Everyday: Lapis Lazuli

I had left the visible, physical blue at the door, outside, in the street. The real blue was inside, the blue of the profundity of space, the blue of my kingdom, of our kingdom!… the immaterialisation of blue, the coloured space that can not be seen but which we impregnate ourselves with… A space of blue sensibility within the frame of the white walls of the gallery.

Yves Klein, 1928–1962, Selected Writings

For those who mined lapis lazuli from the mountains of Afghanistan millennia ago, a lowly beginning by any standards, such a meteoric ascendancy to the objets d’art of the Medici and the chapel ceilings of the Scrovegni could never have been imagined. As the Silk Road opened up trade across Europe via the mountains of Badakhstan and on to Venice and beyond, an increasing number of artists and craftsmen discovered the rare beauty of lapis lazuli and its pigment ultramarine.

The magnificent effects of the light-reflecting gemstone, drawn laboriously by grinding and pummelling, captured the eyes of those who could afford to commission artworks including it. Artists bankrupted themselves to provide it to illustrious clients, and patrons used it to flaunt their wealth and influence. However, the continued use of ultramarine was made possible centuries later as artists with less prosperous customers sought a substitute for the pigment more costly than gold.

Thankfully for the art world, Guimet and Klein came forth in the 19th and 20th centuries with synthetic ultramarines, thus ensuring that art’s most prized pigment could continue its glorious journey through the history of art. No pigment has ever grown to be more symbolic of wealth and power in tandem with a deep association with the Virgin in her blue robes. Lapis lazuli and its pigment ultramarine captured human hearts long ago and seem set to remain there for centuries to come.