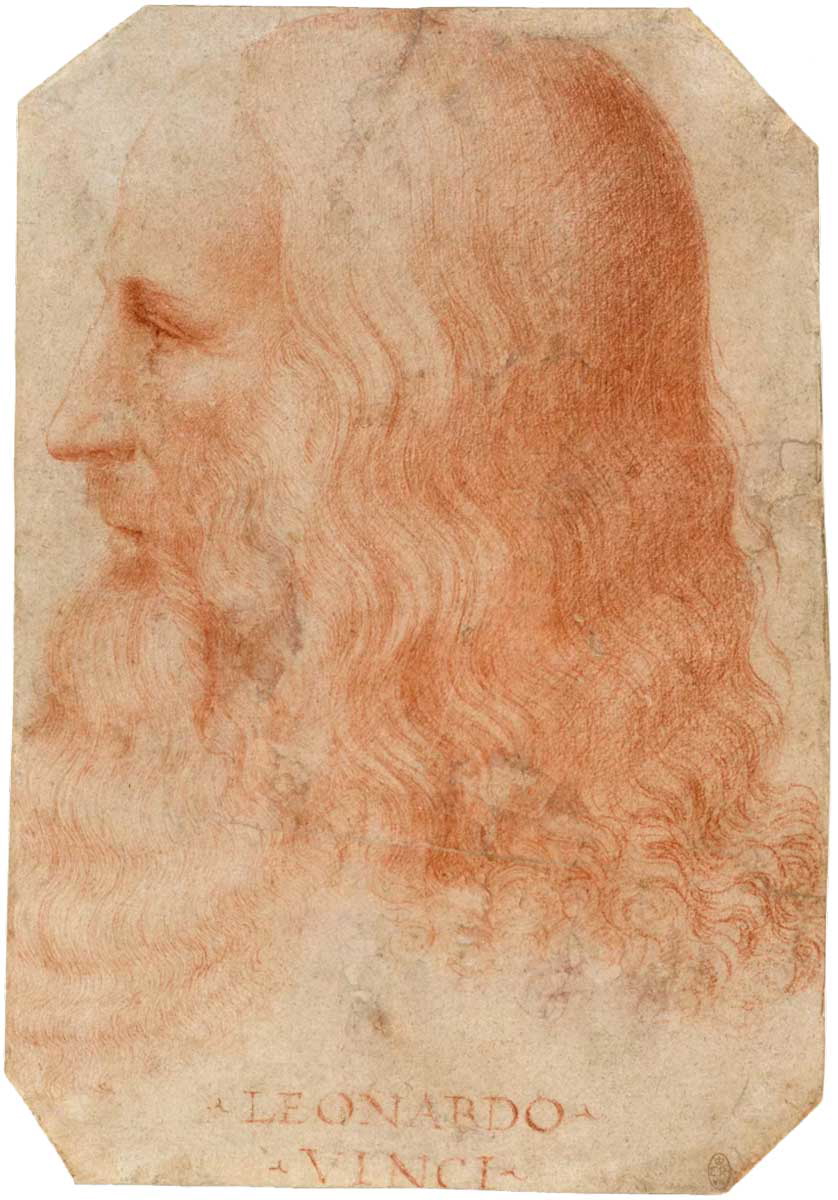

In the crucial decade of the 1490s, Leonardo da Vinci’s endless pursuit of the inner workings of natural phenomena led him to develop from being a gifted artist to pursuing a deeper scientific study of both nature and the prevailing optical theories. His last painting, Saint John the Baptist, is a masterpiece of ambiguity and enigma in which Leonardo distilled all his effort, learning, and imaginative skill.

Leonardo’s Optics

The painting practice of Leonardo da Vinci is evidence of the confluence of science and art in one personality. Leonardo did not at all segregate these two fields from each other. The man who could write that “art without science is not art all” practiced what he preached, and the few completed works he left to posterity attest to this dictum. In particular, the science of optics—long pursued as the study of light from ancient times—fascinated Leonardo. He wrote: “Of all the studies of natural phenomena the study of light gives the most pleasure to those who contemplate it.”

The pleasure of which he wrote is visual, a component of both the practice of painting and of viewing a painting. The contemplation was for Leonardo, a more philosophical pursuit. This would chime with his attitude towards the acquisition of knowledge through the medium of the senses.

This is perhaps why he addresses the study of light itself and not the study of optics for itself. Instead, Leonardo used his optical studies as an aid for his direct observation of natural phenomena. This article will explore the role of optics in Leonardo’s painting practice, how his scientifically informed practice changed, and look at a painting from the end of his career which marks the culmination of a life’s effort.

Art and Science

Leonardo’s prime teacher was nature. His obsession with the phenomena of the natural world is well documented in his copious writings, sketches, and diagrams. It is also evidenced in the artifacts he left behind in the form of his few completed paintings. With this in mind, we see that Leonardo’s study of optical theory—which he began to undertake at least as early as the 1480s—was not for itself. For him, optical theory was a gateway for the acquisition of a deeper knowledge of nature.

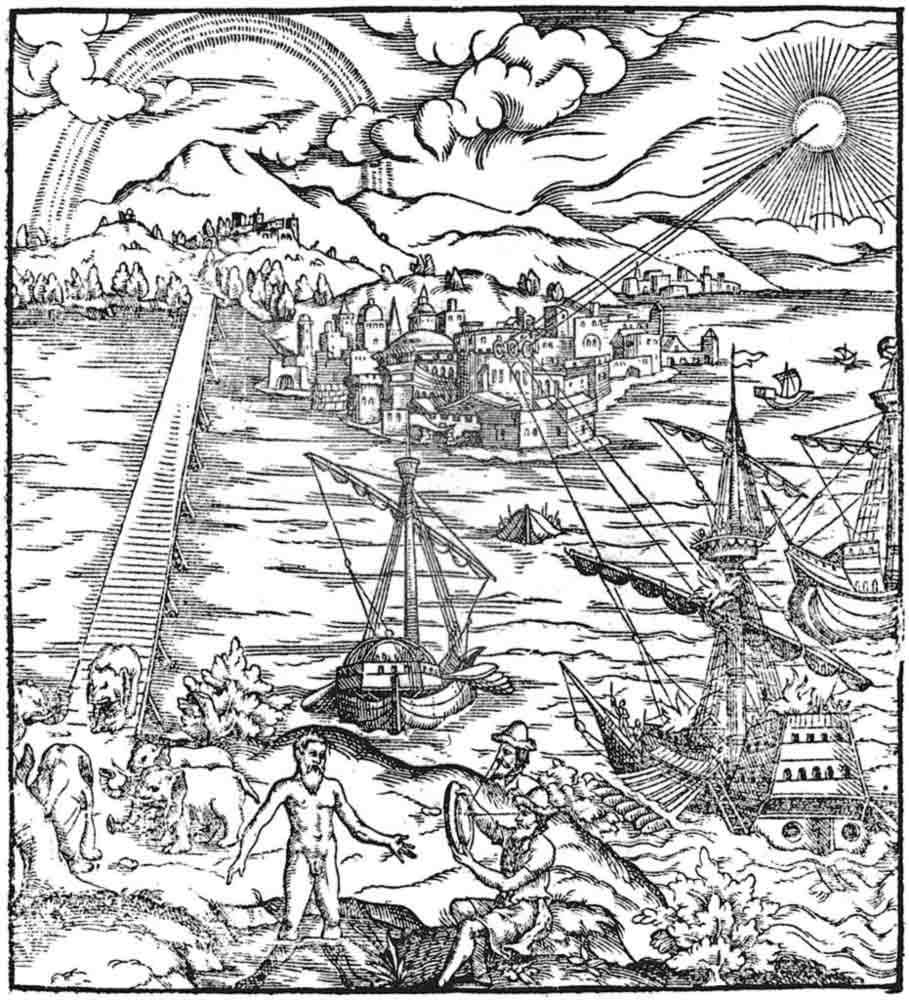

Theories of optics had a long history by the time of the Western Renaissance. Views on the subject were propounded by mathematicians and philosophers as far back as the Classical era in Greek culture. The Greek geometer Euclid especially was to exert an enormous influence over the subsequent development of the field. Together with Euclid’s rigorous mathematical optics, the natural philosophy of Aristotle persisted down to the Middle Ages, and to the scholarship of Persia and Arabia.

It was through one Islamic scholar of the 11th century, as well as an Italian, that Leonardo developed his optical knowledge. The two treatises that inspired him were De Aspectibus (On Vision) by Alhazen and Questiones Super Perspectivam (Questions on Optics) by Biagio Pelacani of Parma.

From Alhazen, Leonardo gleaned knowledge of light reflection, refraction, the propagation or diffusion of light, and the overall conviction that mathematical reasoning was a fundamental partner to observation. The latest scholarship suggests that Leonardo read these works while working for the ducal Sforza family in Milan in the 1480s and 1490s. However, not all agree. Francesca Fiorani, for example, has plausibly argued that Leonardo may have read Alhazen earlier. It is certain that Leonardo was applying himself to optics in his thirties at the latest. These studies were decisive for the painter’s evolving practice. But it was a single minute discovery rooted in observation that, in tandem with optical theory, transformed how Leonardo saw the world, the objects in it, the eye, and his practice.

Leonardo’s painting centered on what he termed “percussione” or the action of light on surfaces. He also studied the anatomy of the eye both for the sake of physiological knowledge and in relation to the study of light.

In the year 1492, he had an epiphany. Leonardo observed the physical adaptation of the pupil to varying intensities of light. He realized that the pupil dilated in darker conditions and contracted in brightness. This realization had a crucial impact on his art from that moment onward, in that he perceived that the eye saw a great deal more detail in dimly lit conditions.

At least as early as—and probably at the time of—Leonardo’s realization, he adjusted his studio conditions. The knowledge of greater visual acuity in dim light led him to adopt it while at work. As he chided his fellow painters for working in different lighting conditions to those they were depicting, it was a matter of course that he followed his own advice.

Leonardo’s great later paintings for the most part exhibit muted lighting and are explorations of visuality itself, as much as depictions. His advice on the painting of portraits is informative: “Do so in dull weather, or as evening falls…[for]…softness and delicacy.” The later pictures would seem to be faithful to Leonardo’s observation that when the eye is in a covered location, the scene it sees is more luminous.

The date of Leonardo’s acquaintance with Alhazen’s optics is not known but Francesca Fiorani suspects that it may predate the Annunciation of c. 1472-76, Leonardo’s first single-handed painting. Fiorani has detected Alhazen’s influence in his method of coloring shadows in the picture.

What is certain is that Leonardo rebutted the conventional Renaissance hierarchy of learning in his studies and art. Conventional wisdom placed natural philosophy and physics above geometry and mathematics. However, Leonardo’s notebooks show that he didn’t see these branches of knowledge as a hierarchy. He sought to integrate them for the sake of a more holistic understanding. The only hierarchy in his conception of the world was in the subordination of humanity to nature. All arms of the pursuit of knowledge he saw as compatible and mutually reinforcing.

Leonardo’s optics cannot be fully isolated from his painting practice. Nor can it be isolated from his general philosophical outlook that maintained that knowledge is obtained and distilled through the senses, especially the visual sense.

In his painting practice, Leonardo’s procedure varied, as noted by Francesca Fiorani, between and within paintings. His restless pursuit of naturalistic representation makes a systematic categorization of his works and stylistic periods problematic. His efforts were not directed towards the achievement of a “style” of painting so much as a faithful rendering of worldly phenomena. As he wrote: “Of all the studies of natural phenomena the study of light gives the most pleasure to those who contemplate it.” Here, Leonardo’s obsessions are summarized and, tied together—they include the study of nature and reflective visuality. Indeed, the artist held that painting was superior to poetry and music. He observed that one can see the entire composition and the parts of a painting simultaneously, unlike with other art forms.

Despite this dismissiveness of poetry, Leonardo studied it, had many books of poetry in his possession, and made his own literary compositions. In particular, he was influenced by the Neoplatonist love poetry of the Florentine Medicean court at which he worked for a time. This philosophical bent which inferred a spiritual significance from the physical, and a mystical union through love became important to him, as we will see.

In Leonardo’s personal system of the faculties, he allied what he called fantasia or “imagination” with “the higher powers of thought.” As such, imagination was central to his science. Also integral was his conception of the microcosm/macrocosm relation—for him, man was a “lesser world.” Historian Martin Kemp saw this relation as existing in Leonardo’s mind as both a poetic image and scientific causation. As man was for Leonardo a “lesser world,” Kemp extrapolated that his view of the universe required “a supreme designer, some motive force—even if its ultimate nature was indefinable.” Thus, Leonardo’s Saint Annes and John the Baptist were “divinely favoured intermediaries” who possessed the secret by inspiration. Leonardo thereby fused the Christian mystery of the Incarnation of Christ and human salvation with the objective of the natural philosopher: the inquiry into causes.

Even in his early career, Leonardo combined sacred poetics and a thoroughgoing scientific approach in his painting. The famed Annunciation which he painted in his early 20s has been examined by scholars, and Francesca Fiorani has observed that the blurred edges of Leonardo’s shadows in the picture are rigorously calculated. This is significant and unique for its time, as only the clear edges of astronomical shadows were analyzed up to that point.

From Artifice to Art: The Waning Influence of Alberti

At the time of Leonardo’s youthful apprenticeship and throughout his 20s and 30s, the influence of Leon Battista Alberti was pervasive in the theory of art and vision in Tuscany. Alberti proposed the “pyramid” of vision as a summation of the operations of the eye. This pyramid described the convergence of the images of the objects of the world on the apex of a pyramid which was supposed to be a single point in the eye. Kemp has noted that by Leonardo’s time, Alberti’s theory was conventional in the “painter’s science.”

The Albertian apex as an indivisible point in the eye was derived from the ancient geometry of Euclid. It was the prevailing orthodoxy for centuries but with the optical theories of the Late Medieval Period and Renaissance, it had been refuted. However, Leonardo initially accepted the Euclidian conception of vision via Alberti, writing that the virtu visiva (“power of vision”) was located at a point in the middle of the pupil at the extremity of the optic nerve.

This conventional “painter’s science” was in fact no science at all. It was rather an artificial simplification adapted to the construction of pictorial compositions. Medieval optics presented a more complex picture of the structure of the eye and of vision itself. Alberti derived the concept of the centric ray from Medieval optics, notably from the Islamic scholar and scientist Alhazen. Alhazen observed that this ray was the only one to pass into the eye unrefracted. In Alberti, there is neglect of the optical observations on the refraction of light in the eye. Kemp has pondered Alberti’s simplification and wondered whether he did this for the sake of clarity or on the point of aesthetic and philosophical principle. Either way, Leonardo absorbed and accepted the Albertian summary of vision and perspective well into the 1490s.

Martin Kemp has lamented the general scholarly focus on the early optics of Leonardo da Vinci in the 1480s and 1490s at the expense of his late optics. Leonardo’s later conception is in fully developed evidence after 1508 at the latest, in the so-called “D” manuscript of his notebooks. Yet the 1490s was a transformative decade in Leonardo’s art and learning. He realized then that the Albertian outlook on perspective and vision was outdated and in conflict with the Late Medieval optics of Alhazen, Pecham, Witelo, and others.

In around 1492, Leonardo observed the physiological adaptations of the eye to changing light conditions, discovering pupil dilation in dim light. Henceforth he was to prefer working in dim conditions, as the eye was at its most perceptive regarding tonal variations of light and shadow. He wrote of the “subtlest shadows in the light part and the subtlest lights in the dark parts,” and of the heightened perception of the details of faces in dark doorways. This revelation accounts for much of his later art, and for the delicacy and nuance of the great later paintings.

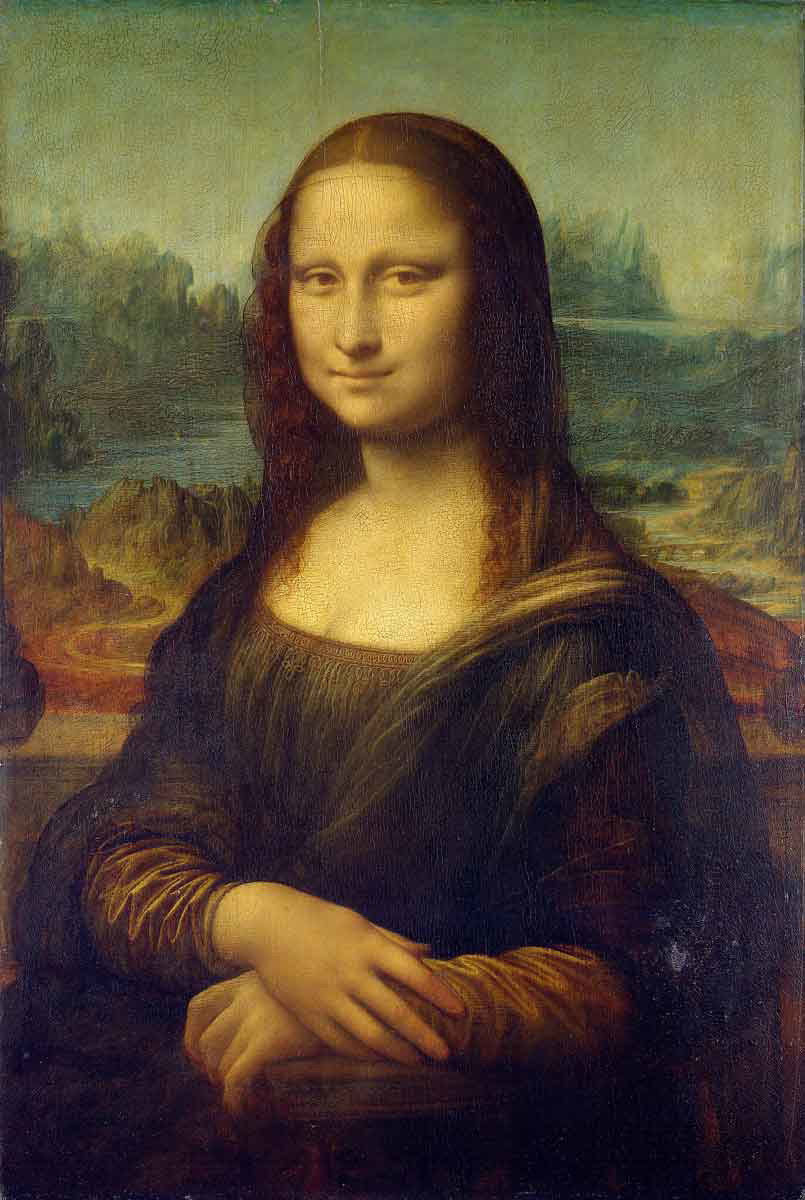

Painter and Prophet: The Late Saint John the Baptist

Kenneth Clark wrote of Saint John the Baptist by Leonardo that it is “the eternal question mark, the enigma of creation.” Purportedly Leonardo’s last painting, Saint John the Baptist marks the culmination of a lifetime’s learning and the high point of the aesthetics of subtlety and ambiguity. In his categorization of the ten functions of the eye, the artist had long since ranked light first, with shade second. Color for Leonardo was the fourth function. Just so, his later work muted color and concentrated on the intricate and precise play of light that, intersecting with shadow, created its own vividness and naturalism. As Fiorani has noted, the technique of chiaroscuro (literally, “light-dark”) became the basis for pictorial composition. Chiaroscuro in painting creates strong light and dark contrasts to suggest realistic volumes in space.

The John the Baptist painting is Leonardo’s late optics “embodied.” John was the intermediary and messenger of the coming of Christ to save humanity, the biblical figure through whom “all men might believe,” as the first chapter of the Gospel of John has it. Another elaboration of the theme of the messenger occurs when we see John as the cipher or means through which Leonardo communicates with the viewer with his aestheticized or poetic optics of light. Leonardo had read the Gospel of Saint John which relates the story of John the Baptist, and the image seems to realize in paint the words “the light shineth in darkness, and the darkness overcame it not.”

Indeed, the picture and the figure of John the Baptist itself have an apparitional quality. Leonardo’s object, as well as means, is the chiaroscuro with which he makes apparent the divine mystery. His obsessive and minute variations of tonality within the picture, especially on the face and upraised arm are as evident here as in the Mona Lisa. But the Mona Lisa shows a concern with the nuance of flesh tones that is counter-balanced by a mystical landscape. John the Baptist, however, has the exclusive aim of rendering flesh tones bathed in warm, golden, and descending light.

By virtue of Leonardo’s figuration of the text in paint, there is a poetic sensibility at work. But also, in terms of the internal qualities of the picture itself—the nuanced sfumato (“smoked”) effects and the revelatory chiaroscuro—there is a poetry of ambiguity. The expressive warmth of the eyes and smile is an analogous prefiguring of the light and humility of Christ.

The picture’s “unresolved complexity” has been noted. Not least is this the case when we see that Leonardo has used the science of painting to evoke in imaginative artistry a haunting image. With the divine mystery, he couples a situational one: there is no spatial or temporal setting other than the light-dark contrast. This contrast signals the emergence of humanity from moral blindness and despair after the sacrifice of Christ.

Martin Kemp maintains that “in a sense the painting is about light.” As well as being about light, the picture itself acts as a torch with its arresting chiaroscuro. Just as John the Baptist points the way to the coming of the true light, Leonardo makes tangible his precepts of painting in the physical and pictorial artifacts. Yet within the pictorial space, there is also intangibility—even John’s flesh is gilded by light as if made abstract. Kemp has observed that the “tonal effects [are] meltingly subtle.”

Leonardo’s poetic ambiguity seems to operate on layers of contrasts that somehow cohere in his treatment of light and shade: flesh and spirit, light and form, John’s position close to the viewer and his lack of position being outside time and space, the possible doubling of the figure of John and of the idealized Leonardo are some of these. We can find justification for these contrasts being intentional as visual punning in the very meaning and execution of chiaroscuro itself, a compound of light and dark.

Paul Barodsky has written that the picture is an illustration of the words of the Gospel of John and that its meaning is not exhaustible by text. Barodsky wrote that the iconographical text is “never identical to the meaning of painted form.” This is true. Mere iconographical interpretation restricts meaning to verbal precision, while “painted form” (especially in the case of Saint John the Baptist) is more suggestive and open. Leonardo’s image thrives in ambiguity. For example, it depicts the presence of the prophet as a means to literally point beyond his presence and the picture space. The image, therefore, is not formally unified or self-contained in a conventional way. The already cited oscillations between light and dark, flesh and spirit also apply here, as do the contrasts of word and image, and the divine Word which is mysteriously ineffable, contrasting with the naturalistic portrayal of a human figure. This latter contrast relates to another: the proximity of the form of John in a direct specificity and the ethereal Christian mystery of which he is the harbinger.

In a way, the picture could be Platonic in conception as much as Christian, or rather Christian as far as the Christian adoption of Platonic ideas goes. John as an embodied spirit points beyond himself to the Word, the light, and the spirit itself; just as Plato advocated that worldly forms and attributes merely participated in the perfection of the universal Form or Idea.

There is an argument for the picture being an idealized and rejuvenated self-portrait. If true, art and knowledge on the one hand, and divine revelation on the other are placed in analogy. Leonardo became the messenger for painters and scholars, just as he wrote copious notes for planned treatises for the instruction of artists. The divine light of the image thus becomes artistic and scientific enlightenment.

In support of the thesis that this picture doubles as an idealized self-portrait, we can compare another probable self-portrait by Leonardo: that of the young man on the extreme right of the detailed preparatory sketch for an Adoration of the Magi. The young man looking out of the shadowy picture space of the Adoration does bear certain similarities to John the Baptist. The strong nose and the hair match—in the Adoration Leonardo has cropped hair but if grown out it would chime with the luxuriant curls of the John the Baptist, as we see the former already revealing curls looping around the ear.

Leonardo’s late, and perhaps last, picture is both an artifact and a symbol. Evidence of a life devoted to the study of nature, science, and art; it is also symbolic in the sense of “pointing beyond.” John the Baptist’s gesture is emblematic of the picture which, excellent in itself, signifies the necessarily provisional manifestation of Leonardo’s tireless and eternal striving after the secrets of nature.

Bibliography

Charles Nicholl, Leonardo da Vinci: The Flights of the Mind.