The Renaissance era was a time of rapid scientific development followed by a shift in understanding the role and function of art. The position of the artist gradually changed from a no-name artisan to a respected master. This change of attitude led to the development of artistic practices and the rise of workshops, unions, and commission systems. Read on to learn more about the Renaissance workshops.

Art of the Renaissance Workshops

The Renaissance era in European history was the time of revival and reinvention of the ideas of Classical Antiquity through the lens of post-Medieval experience. Instead of stylized, strictly religious and non-realistic art, secular art started to emerge, this time relying on supposed rationality and empirical knowledge. Despite widespread beliefs about the Renaissance, this culture was fully experienced only by select groups and classes. Moreover, the Renaissance culture was not visual but literary, with art following the concepts from treatises on morality and science.

The development of theoretical writing boosted the new approach to art through the studies of perspective, optical effect, and proportions. One of the most important events in the culture of the Renaissance was the shift in the status of an artist. In the Medieval period, artists were considered artisans, similar to potters or weavers. The intellectual component was excluded from their work, just as artistic practice was excluded from the list of respectable occupations. With the rise of scientific and literary culture, art gradually became a sophisticated domain capable of influencing one’s mind and soul. It became fashionable for the privileged classes to study painting and sculpture, and for artists to turn their practice into theory, formulating their ideas on color and proportion.

Among the most important theoretical sources on Renaissance art and its practical structure is the 1550 text The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects by Giorgio Vasari. Vasari was a painter and architect who was a close friend of Michelangelo. Vasari’s piece is the first documented work in the discipline of art history. It is a record of biographies of famous artists from the 13th century to Vasari’s time. Although Vasari made significant errors and assumptions, many of which were refuted by present-day art historians, his book nonetheless provided us with insights into the artistic processes of his era. Moreover, some of the theoretical concepts introduced by Vasari remain in use. For example, the term Gothic is applied to architecture or Mannerism to the style of painting.

Renaissance Patrons

The importance of the artist’s role in the creative process gradually developed, yet in the Renaissance era, there was another figure much more important for the creation of art. The principal figure was the patron, or the commissioner—someone ready to provide an idea and pay for it. In that era, funding arts brought not only fun but a promise of a secure afterlife. By decorating its city and funding impoverished artists, a patron hoped to earn forgiveness for their sins and gain a ticket to heaven.

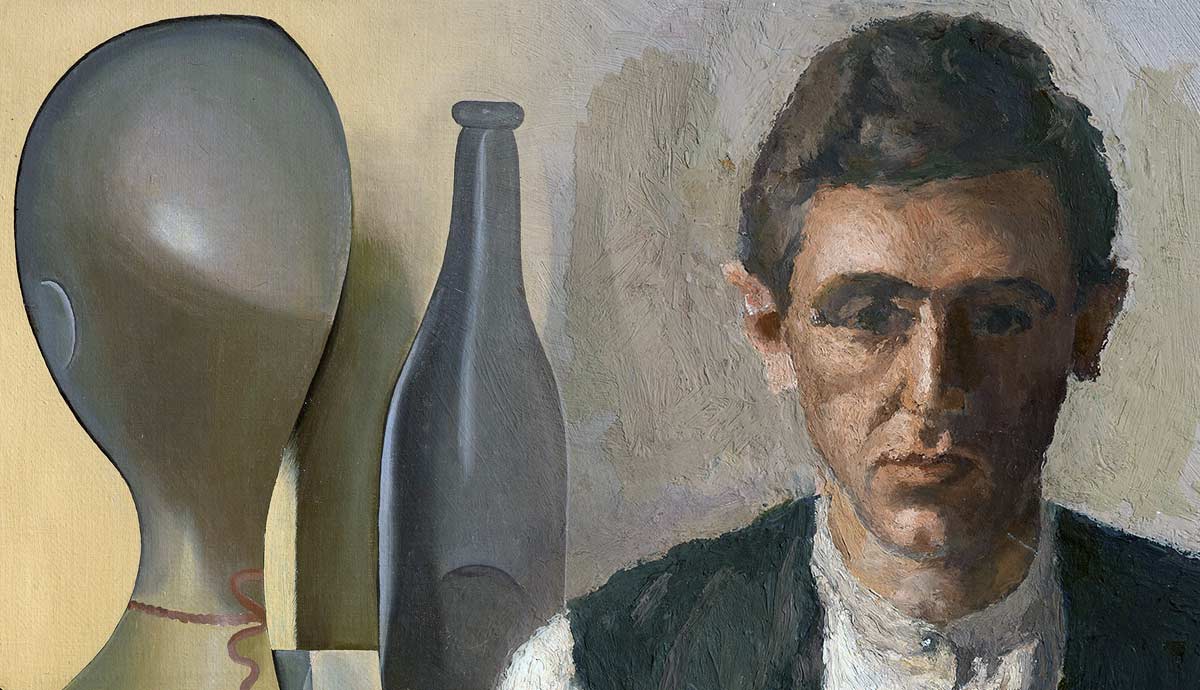

The overwhelming majority of art that was being made was religious or mythological, yet secular painting also began to rise in the form of portraiture. Sometimes, a painting depicting a Biblical scene could include the image of the patron among the characters, thus highlighting the commissioner’s identity and their holiness. Even secular portraits often included elements of mythological allegories or symbols. The goal of portrait painting was not to copy the exact looks but to serve as a piece of the personal brand of the commissioner. It showed how the commissioner preferred to be known and remembered.

The most famous name associated with Renaissance art and its patrons was, of course, the Medici, who ruled Florence and Tuscany for several centuries during the Renaissance era. Often romanticized as a noble dynasty of art lovers, the Medici were in fact a ruthless and corrupt family that built its power by spilling blood and arranging betrayals. The family generously funded art and architecture, using it as political and personal propaganda.

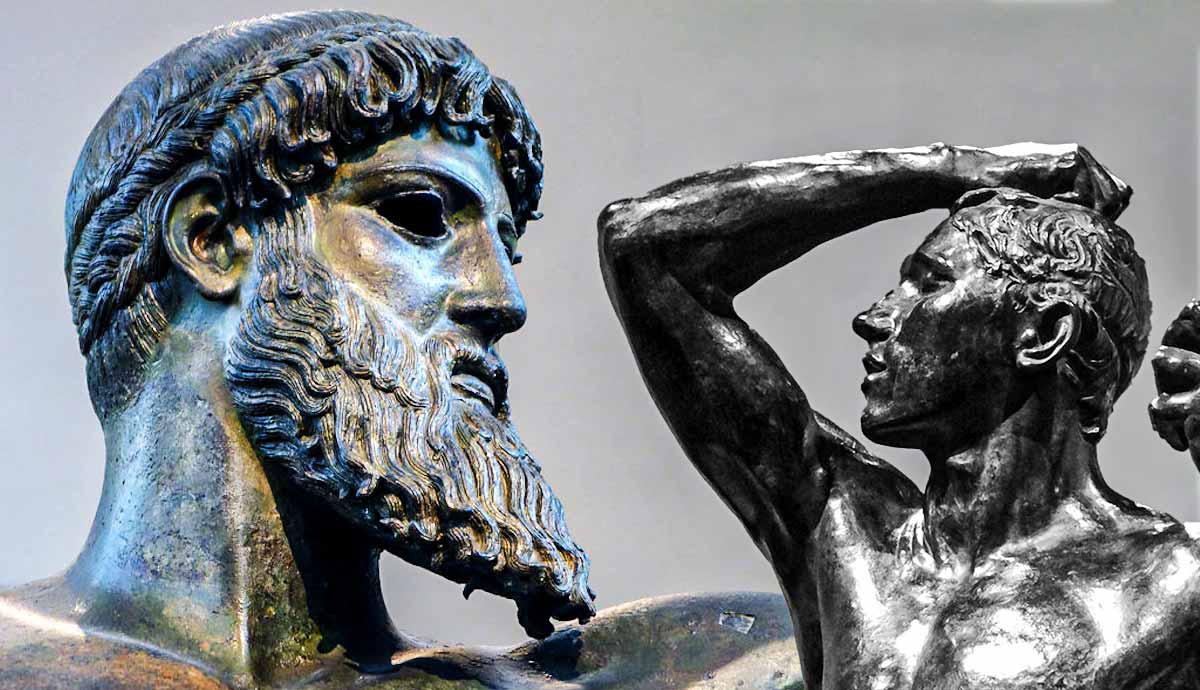

The legendary Renaissance sculptor Michelangelo was helped by Lorenzo Medici, the most famous and infamous member of the family. While in his early teens, Michelangelo apprenticed in a sculptor’s workshop, where he was noticed by Medici. He soon moved into his patron’s house. However, that close connection and favor barely affected Michelangelo’s political stance (or, on the contrary, contributed to it). The sculptor was a devout Republican who opposed the reign of the Medici over Florence.

In 1504, after the Florentine uprising resulted in the temporary exile of the Medici, Michelangelo created perhaps the most famous and recognizable of his works—the monumental David. David was the Old Testament hero, a young boy who defeated the giant Goliath in battle. For the Florentines, who recently overcame a suffocating period of the tyranny of the omnipotent and evil Medicis, the sculpture became the symbol of justice and liberty.

Bottega: The Renaissance Coworking Space

Integral to the Renaissance notion of artistic activity was the concept of Bottega—a workshop usually led by one accomplished master who employed dozens of assistants and apprentices. To become an artist, one had to serve years as an apprentice, grinding pigments, mixing paint, gradually learning their master’s style and skills. To run a workshop officially, the artist had to become a member of a guild—a union regulating economic and other relations between bottegas and their clients. The competition was fierce. The demand for art was higher than ever and fights for customers would often be resolved by the guild’s court.

Bottegas were loud and crowded places with never ending, fast-paced work. The institute of artistic apprenticeship was far from new at the time, yet in the Renaissance era, it blew up significantly. Artistic production grew in scale and pace, turning into a precursor of conveyor belt production. The increasing number of assistants and emerging artists helped the master secure financial prosperity, accepting astonishing numbers of commissions. Still, despite the involvement of dozens of unnamed employees, the clients addressed their praise only to the master in charge of the workshop.

Commissions: How to get the Price Right?

The overwhelming majority of the Renaissance artistic practice was commissioned. The notion of personal style was only developing at the time, and most artists were valued not for their vision but for their ability to fit the client’s needs. The final price was determined by factors such as the number of human figures included and the complexity of details, poses, and decorations. Since the workshop was a structured hierarchical unit, the price depended on the identity of the person working on the commission.

The most expensive pieces available only to the select few were painted by the headmaster. The cheapest versions were made by his assistants.

The price of a finished artwork also depended on the materials used. These include pigments, base materials, and gold leaf for decoration. Quality pigments were expensive and had significant and readable meanings in the overall composition.

For instance, natural ultramarine, the deepest and boldest of blue pigments, made from lapis lazuli, was imported from Afghanistan, which increased its price drastically. Finding an alternative was hardly an option since ultramarine was a traditional choice for the blue cloak of the Virgin Mary, as well as an overall subtle mark of the commissioner’s wealth. Other blue pigments were available on the market for a smaller price, yet none of them had such a deep undertone and lasting color intensity.

The number of lapis lazuli used was usually fixed by a contract between an artist and his commissioner, yet artists had to purchase the materials before receiving the payment for their finished work. The legendary innovative printmaker Albrecht Dürer never missed a chance to complain about ultramarine costs in his notes. According to an entry made in 1521 in Antwerp, he paid for a small amount of ultramarine almost a hundred times more than for regular pigments.

Women in Renaissance Workshops

Although often erased from historical records, women in the Renaissance nonetheless participated in the arts from the sides both as artists and commissioners. Their opportunities for education and apprenticeship were limited, yet there is still a list of accomplished women of the Renaissance era. In most cases, a woman could access an artist’s workshop if she was related to a male painter, like Artemisia Gentileschi, the daughter of Orazio Gentileschi. However, there were important exceptions to this rule.

Plautilla Nelli was a Florentine nun and a self-taught artist who created frescos, including the first known image of the Last Supper created by a woman artist. As a nun, Nelli had limited access to the outside world, so her fellow sisters were her only models. For that reason, the critics often noted the excessive femininity of her male figures. Plautilla Nelli was one of the few women mentioned by Giorgio Vasari in his collection of artistic biographies.