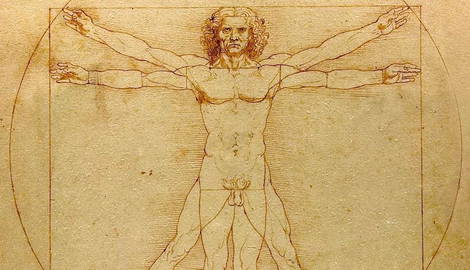

At first glance, it seems like a simple sketch: a nude male figure within a circle and a square. But Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man is anything but ordinary. Those familiar lines form a fascinating blueprint of Renaissance ideals, revealing layers of artistic and scientific genius that were centuries ahead of their time.

The Ancient Seed of Inspiration: Revisiting Vitruvius

Long before Leonardo put pen to paper, the Roman architect Vitruvius envisioned a world governed by harmony and perfect proportions. He published De Architectura, his foundational text, in the 1st century BCE, arguing that the human body was the ultimate model of symmetry and ideal proportions.

Vitruvius posed a geometric riddle that would captivate readers for centuries: could a man be drawn so perfectly that he could fit simultaneously inside a circle and a square? Early attempts to bring Vitruvius’s idea to life were unsuccessful. It wasn’t until the Italian Renaissance that Leonardo da Vinci, with his insatiable curiosity for all things art and science, finally figured out the solution.

The Synthesis of Art and Science in the Vitruvian Man

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) is remembered as the ultimate Renaissance man. He approached the Vitruvian challenge with tools no one had possessed prior: empirical observation, anatomical precision, and a unique ability to see the poetic in the mathematical. Years of dissecting human cadavers—and filling notebooks with studies of torsos, limbs, and organs—had given Leonardo a deep scientific understanding of anatomy. Unlike his predecessors, he did not rely on guesswork to draw the Vitruvian Man around 1490.

The genius of the Vitruvian Man lay not only in the perfectly rendered figure but in its precise placement. Leonardo devised the perfect solution to Vitruvius’s ancient puzzle: two separate centers of rotation. The square anchors itself at the figure’s genitals, and the circle at the navel, allowing the figure to expand naturally within both shapes without distortion. Leonardo’s version even corrected inaccuracies in Vitruvius’s original text.

Centuries later, Leonardo’s synthesis of art and science can still surprise us. In a 2025 study published in the Journal of Mathematics and the Arts, a London dentist identified something new in the Vitruvian Man. According to Dr. Rob Mac Sweeney, an equilateral triangle “hiding in plain sight” between the man’s legs corresponds to a principle of dentistry called the Bonwill Triangle. This triangle is formed by the contact point of the mandibular central incisors and the right and left mandibular condyles.

The Bonwill Triangle, introduced in 1864 by William Bonwill, illustrates the optimal function of the human jaw. According to Dr. Sweeney’s study, Leonardo used an identical triangle to relate the Vitruvian Man‘s “static positioning to its dynamic capability.” Indeed, its appearance in the 15th-century drawing demonstrates Leonardo’s keen observational skills and interdisciplinary approach to depicting the human form.

The Humanist Manifesto: Vitruvian Man as the Universe’s Measure

Beyond anatomy and geometry, Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man also exemplifies the tenets of Renaissance Humanism. Starting in Italy, Renaissance-era thinkers revived an ancient belief that a human being is a microcosm: a miniature universe that mirrors the divine order and universal principles, such as harmony and proportion. Humanism emphasized the value of critical thinking and celebrated the human form.

In the Vitruvian Man, both the circle, with divine and spiritual associations, and the square, a symbol of earth and rationality, converge in the human body. Leonardo’s drawing is more than a precise visualization of proportions—it is also a metaphysical map of the body, mind, and cosmos in perfect harmony. It is the essence of Renaissance humanism, wherein a man is not merely a subject of the universe, but its measure.

The Enduring Echo: Why a 500-Year-Old Drawing Still Defines Genius

Today, the Vitruvian Man is just as resonant and revolutionary as it was when Leonardo created it. The image is a global icon, appearing everywhere from euro coins to NASA mission patches. It is a living diagram of Renaissance thought: art rooted in science, geometry animated by spirit, and proportion transformed into poetry.

After 500 years, the Vitruvian Man continues to define genius, not only because of what it reveals about the Renaissance, but because it invites us to keep asking questions. The Vitruvian Man may still be holding onto more secrets. What else might be hiding in Leonardo’s lines?