Many men worked tirelessly behind the scenes to help create the United States. They came from various backgrounds and beliefs. All shared one basic yet solid conviction. The colonies needed their independence from Great Britain. Their strength in politics, law, and their desire for a new and improved country was at the forefront of their public service. Here’s a look at four of these men, who each had an important part to play in the independence of the United States.

1. Richard Henry Lee – VA

Born to an aristocratic family, Lee attended private school in Yorkshire, England. Upon returning to Virginia, he unsuccessfully attempted to form a militia troop in his neighborhood. He was a planter and a politician and excelled at being a bit of a rabble-rouser as the revolution came to fruition. He had poor financial skills and often struggled to make ends meet. In 1757, he was appointed a justice of the peace and, shortly thereafter, to the Virginia House of Burgesses.

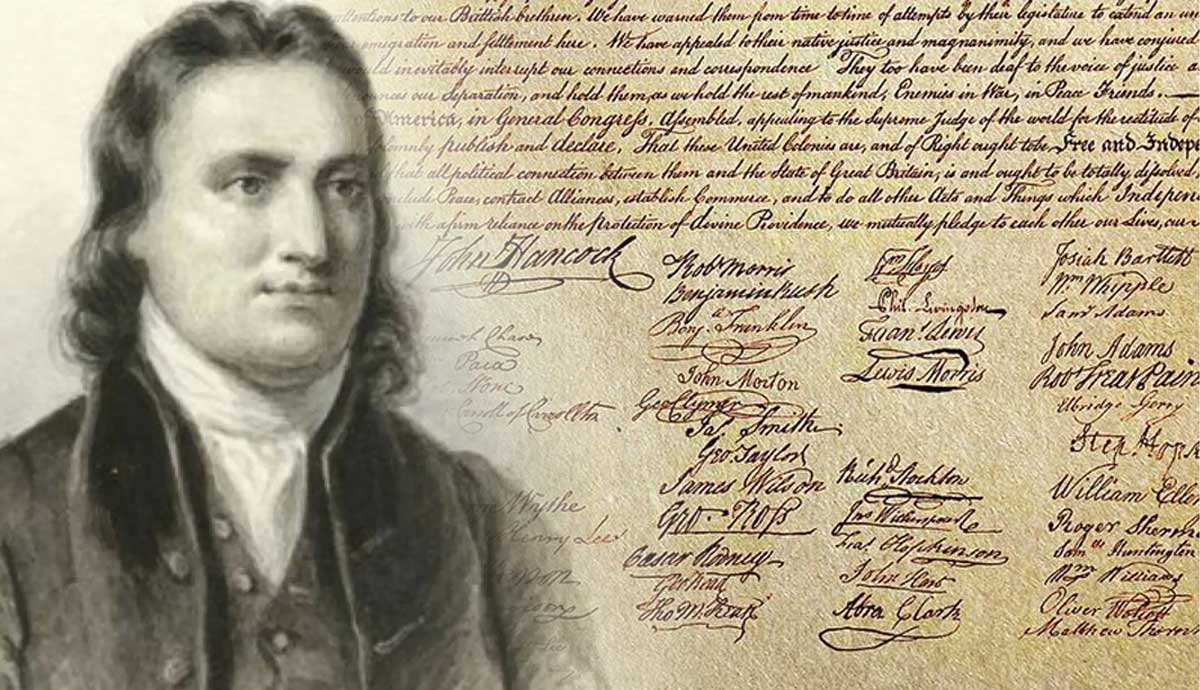

Raised in a conservative environment, Lee was radical in his social and political views. In March 1773, Lee—with the help of Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, and several others—put his idea into action when they created the first intercolonial Committee of Correspondence, approved by the House of Burgesses on March 13, 1773. An excellent orator, Lee was elected to attend the first Continental Congress and served on many committees. He offered the Resolutions for Independence to the committee of the whole in 1776, including introducing the resolution that would lead to independence. Thus, he is one of the most instrumental and essential supporters of the Declaration of Independence and the United States.

Throughout the Revolutionary War, Lee served in Congress as well as the Virginia House of Burgesses. In 1783, he was selected as the president of Congress. He favored strong states’ rights and opposed the Constitution at the vote of 1787, as he believed it concentrated power on the federal government. Lee was elected the first State senator from Virginia under the new federal government in 1789 and served until his death in 1784. Prior to the Revolution, Lee openly denounced slavery as evil. He even went so far as to favor the vote for women who owned property, an uncommon opinion at the time.

Richard Henry’s brother, Francis Lightfoot Lee, also attended the Continental Congress in Philadelphia and was one of the fifty-six signers. Interestingly, the Lee brothers were the only siblings to sign the Declaration of Independence among all the delegates in attendance.

2. Elbridge Gerry – MA

Elbridge Gerry was a graduate of Harvard and worked in his family’s shipping business before changing careers and taking up politics. He was first elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives and served as a member of the first and second Continental Congresses. On April 18, 1775, he attended a meeting of the Council of Safety in Arlington between Lexington and Cambridge. He barely escaped British troops marching towards Lexington and Concord.

While serving in the Continental Congress, Gerry’s specialties were military and financial matters, to which he earned the nickname “soldiers’ friend” for his advocacy of better pay and equipment. Although he disapproved of standing armies, he did recommend long-term enlistments. Gerry presided over the committee that produced the Great Compromise but disliked the compromise itself. He was antagonistic and objected to almost everything he did not propose. Initially an advocate of strong central government, Gerry rejected and refused to sign the Constitution because it originally lacked a Bill of Rights, and he believed it was a threat to republicanism.

Gerry was named President of the US Treasury Board, afterward serving as Massachusetts representative in the US House of Representatives. In 1797, he was deployed to France on a diplomatic mission but returned shortly thereafter due to strained relations with France; he then ran for Republican governor in 1801 and 1812, both of which he lost. Gerry did secure the governorship election in 1810, serving until June 1812. Later that year, he was elected Vice President under James Madison. He held office until his death on November 23, 1814. Gerry collapsed on his way to the Senate and died. He is buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington DC.

Gerry would not be remembered not for his participation in the political portion of the revolution, but rather for his controversial attempt to redraw congressional districts in his favor while governor of Massachusetts. Near the end of his two terms, scarred by partisan controversy, the Democratic-Republicans passed a redistricting measure to ensure their domination of the state senate. In response, the Federalists heaped ridicule on Gerry and coined the term “gerrymander” to describe the salamander-like shape of one of the redistricted areas.

3. Thomas Lynch Jr. – SC

Thomas Lynch Jr. hailed from a very refined family. His father, Thomas Sr., was an influential and prosperous rice planter and was very interested in politics. Thomas Jr. was given all the best options for education, including studying at Eton College and Cambridge University in London, followed by law studies at Middle Temple.

In 1772, Lynch returned to South Carolina as an extremely accomplished and refined man ready to take on society. Upon his return, he decided to forgo practicing law and instead got married and settled down as a local planter and politician. Lynch Jr. served in the first and second Provincial Congresses while Lynch Sr. attended the first Continental Congress.

During a tour as a captain in the South Carolina regiment of provincial regulars, Thomas Jr. was struck by a disease that would affect his health for the rest of his life. At the same time, his father had a stroke while attending the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Thus, Thomas Lynch Jr. was appointed to succeed his father and traveled to Philadelphia to care for his ill father and attend the congressional session. Lynch Jr. signed the Declaration of Independence along with his fellow delegates and then headed back to South Carolina with his ailing father, but they would only make it to Annapolis before Thomas Sr. passed away.

In 1779, with his own health and recovery in mind, Thomas Jr. and his wife Elizabeth left for the south of France. Sadly, the ship was lost, and the couple perished at sea. Although he was not the first of the signers to die, he was the youngest at the time of his death at age 30.

4. Button Gwinnett – GA

Born in England, Button Gwinnett arrived in Savannah, Georgia in 1765 and became a merchant. After failing at that venture, he purchased St. Catherine’s Island and set himself up as a planter. He was active in local politics, winning the election to the Commons House of Assembly in 1769. However, Gwinnett was unable to remain financially stable and had to sell most of his property and possessions by 1773, withdrawing from the public eye and politics as well.

Upon the uptick in events heading towards the revolution, Gwinnett jumped back into politics by rallying the opponents of the Christ Church parish-led Whig party. He succeeded in uniting dissidents into a local coalition. In turn, they elected him commander of Georgia’s Continental Battalion in early 1776. When this election became highly controversial, he stepped aside, allowing Lachlan McIntosh to command the battalion, and instead accepted an appointment to the Continental Congress currently meeting in Philadelphia. There, Gwinnett served on multiple committees and supported separation from England. He voted for independence in July and signed the Declaration in August, along with the two other representatives from Georgia, George Walton and Lyman Hall. Gwinnett then returned to Georgia and became involved in a bitter political battle.

He was eventually named Speaker of the Georgia Provincial Congress. He began to work towards ousting any military officers he deemed less than zealous in their support for the Whig cause. When Georgia’s president and Commander in chief Archibald Bulloch died in Feb 1777, the Council of Safety appointed Gwinnett as his successor.

Gwinnett had proposed a military march into British East Florida, a defensive measure that he argued would secure Georgia’s southern border. But Lachlan McIntosh and his brother George (who had opposed Gwinnett’s election as president and was subsequently arrested for treason) condemned the scheme as politically motivated. The expedition failed, and though he was not elected governor when the new legislature met in the spring of 1777, Gwinnett was exonerated of any misconduct in carrying out the campaign.

Lachlan McIntosh was furious at the clemency given to Gwinnett. He publicly denounced Gwinnett, and in turn, Gwinnett challenged McIntosh to a duel. Though each man was wounded by opposing shots, Gwinnett’s wound was the only one that was fatal. He died May 19, 1777, and was buried in Savannah’s Colonial Park Cemetery. Interestingly, the exact location of his grave is unknown. However, Gwinnett County in Georgia was named for him when it was established in 1818.

Gwinnett’s signature is thought to be one of the least common and most valuable on the Declaration. Since he signed the document and was then killed in a duel with a rival less than a year later, it is one of the rarest signatures of all the Declaration signers. In 1979, a letter signed by Gwinnett brought 100.000 USD at a New York auction, and by 2012, his signature had increased in value to between 700-800K. Today, it is estimated to be worth over 1 million dollars.