While we tend to tell the history of imperial Rome through the Roman emperors, imperial women—wives and mothers—can often be seen in the background influencing and steering events. The archetype for the Roman empress was Livia, the wife of Augustus and mother of the emperor Tiberius. In Augustan propaganda, she was represented as the ideal wife and mother. But later Roman historians suggested she was ruthless and power-hungry, willing to do anything, even kill, to ensure power for her son and, by extension, herself. But what do we know about the real Livia?

Civil War and Livia’s Turbulent Youth

Livia Drusilla was born on January 30, between 57 and 59 BCE. She was the daughter of Marcus Livius Drusus Claudianus, from the well-established Claudian senatorial family, and Alfidia, whose father was a famous tribune of the plebs in 61 BCE.

She married a respected senator, and cousin, Tiberius Claudius Nero in 43 BCE when she was 15 or 16; probably the standard age for aristocratic girls. Her husband must have been considerably older as he served as praetor in 42 BCE, for which the minimum age was 40. He must have been almost that age when he married the youthful Livia. She became pregnant quickly, giving birth to their first son, Tiberius, in 42 BCE.

Both Livia’s father and husband sided with the assassins of Julius Caesar against Octavian and Mark Antony. Her father committed suicide alongside the lead conspirators, Brutus and Cassius, following their loss at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE. Her husband then threw his lot in with Mark Antony, Julius Caesar’s military second in command, against Octavian, the dictator’s adopted nephew. He abandoned Antony after his loss at the siege of Perusia and joined Sextus Pompeius in Sicily, again against Octavian, before fleeing to Greece. Livia, her young son in arms, accompanied her husband.

It was only in 39 BCE when new peace talks saw Octavian grant a general amnesty to those who had opposed him that Livia was able to return to Rome with her husband.

Livia and Octavian: An Unlikely Match

According to the surviving sources, Octavian met Livia on Rome’s social scene and immediately fell for her. He therefore divorced his second wife, Scribonia (he had previously been married to Mark Antony’s stepdaughter Claudia Pulchra), on the day she gave birth to his daughter, Julia, his only biological child. Tiberius Claudius Nero was then convinced to divorce Livia, even though she was pregnant with his second child.

Livia gave birth to baby Drusus on January 14 and married Octavian on January 17, 38 BCE. There seems to be no reason for such a hasty postpartum union, which broke social protocols, except for genuine affection. Nevertheless, history points to other reasons for the marriage.

Octavian was trying to rebuild stability among the aristocracy following years of civil war. Livia was well-connected to prominent families from the opposing side. The marriage allowed Octavian to build bridges and Livia’s family to show their loyalty. This is probably why Tiberius Claudius Nero agreed to give Livia away at the wedding, “like a father.” This worked out well for him, as the Claudii Nerones became one of the empire’s most prominent families.

It may also be noteworthy that Octavian divorced Scribonia on the day she gave birth to a girl. Octavian already knew that he needed to secure his position with an heir. The fertile Livia had already given birth to two sons. Apparently, during the wedding, Octavian received an omen of an eagle dropping a white hen with a laurel branch in its mouth in Livia’s lap, which was considered a sign of fertility.

Livia does not seem to have objected to being forced to divorce her much older husband for Octavian, who was only around five years her senior and was the most powerful man in Rome. This involved giving her children up to their father, though he died not long after, allowing her children to be restored to her and grow up in Augustus’s household. But the promised sons of Augustus would never come. Livia’s first pregnancy by Augustus resulted in a stillbirth and complications meant that she could not have any more children. Nevertheless, the pair remained married, and seemingly relatively happy, for 51 years.

Whatever the true story of their romance—love match, political alliance, or both—it would make for a fascinating season of Bridgerton.

The Model Matron

As Octavian—who became known as Augustus in 27 BCE—established himself as pater patriae (father of his country), Livia was presented to the public as the ideal mother. She became the matronly head of the imperial family and represented the feminine ideal that Augustus promoted with his moral legislation.

The contemporary politician and historian Velleius Paterculus, who wrote under the patronage of Augustus and Tiberius, praised Livia for her maternal nature, even when describing her life before her marriage to Augustus. He made certain to note her important familial bonds, her beauty, her piety to family, and her maternal instincts in protecting her children:

“She, the daughter of the brave and noble Drusus Claudianus, most eminent of Roman women in birth, in sincerity, and in beauty, she, whom we later saw as the wife of Augustus, and as his priestess and daughter after his deification, was then a fugitive before the arms and forces of the very Caesar who was soon to be her husband, carrying in her bosom her infant of two years, the present emperor Tiberius Caesar, destined to be the defender of the Roman empire and the son of this same Caesar (2.75).”

As the wife of Caesar, she was the ideal matronly head of household, living modestly in their house on the Palatine Hill, which was a far cry from the Domus Aurea that would be built by Livia’s great-great-grandson Nero. She was known to dress well but not excessively, without elaborate jewelry. She also reportedly made Augustus’s clothing with her own hands, as was the traditional custom.

However, Livia’s life was not one of complete humility. The sources also describe her as receiving exceptional honors to mark her position as First Lady of Rome. Unlike most women, she was given control of her own finances and property, which included international holdings such as copper mines in Gaul and palm groves in Judea. This enabled her to be a philanthropist in her own right, providing assistance after devastating fires, which were common in the tightly packed Roman capital, and providing dowries for poor girls from good families. She also received the right to have statues of her dedicated in public spaces and had her own clients whom she supported, including the grandfathers of the future emperors Galba and Otho.

She also seems to have enjoyed exercising the power she received due to her closeness to Augustus. It was apparently common for ambassadors to approach Livia to intercede with her husband on their behalf, and she also used her influence to help some of her friends out of difficult situations. Philo describes her as having a masculine intellect that Augustus respected:

“But she, as she surpassed all her sex in other particulars, so also was she superior to them in this, by reason of the pure learning and wisdom which had been implanted in her, both by nature and by study; so that, having a masculine intellect, she was so sharp-sighted and profound, that she comprehended what is appreciable only by the intellect, even more than those things which are perceptible by the outward senses, and looked upon the latter as only shadows of the former (XL.320).”

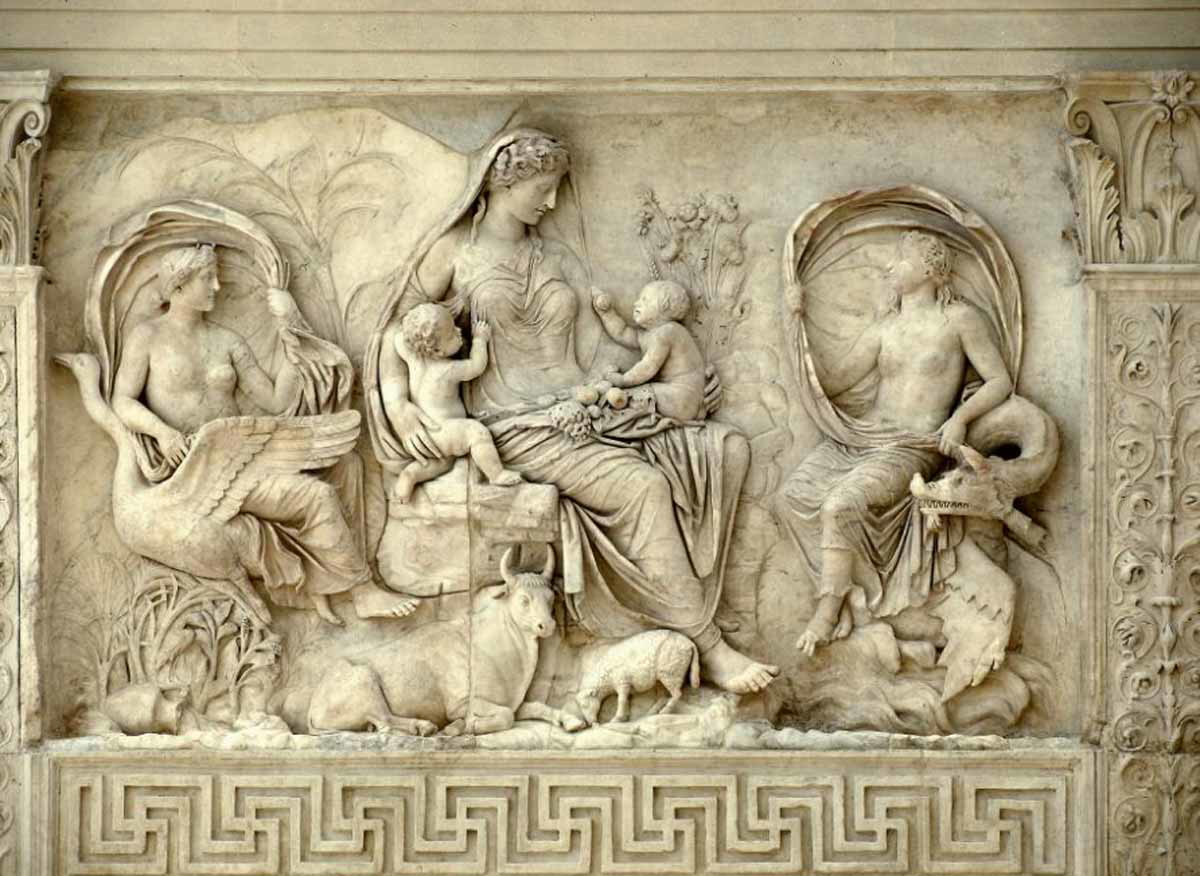

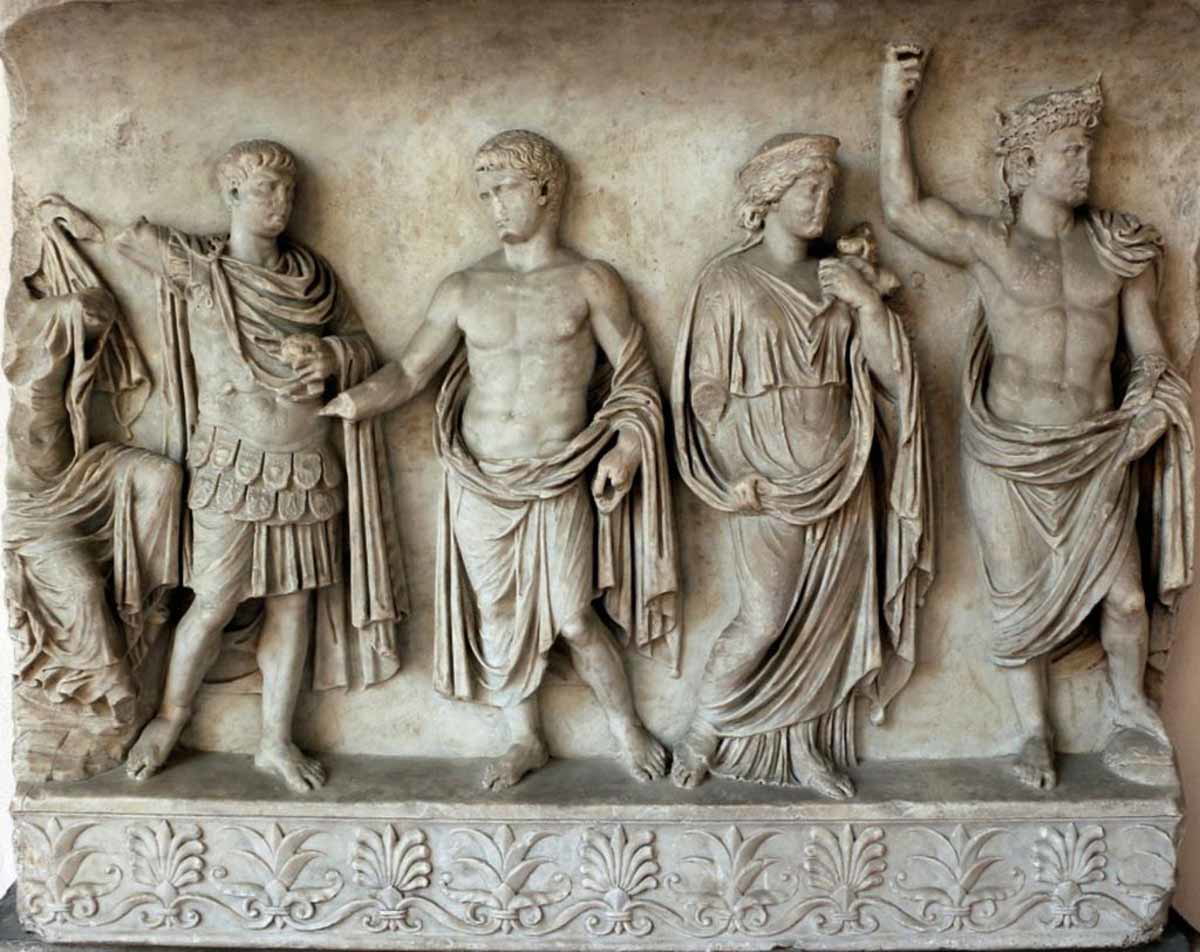

The most visible recognition of Livia as the ideal mother of the Roman state probably came in 9 BCE with the dedication of the Ara Pacis, the altar of Augustan peace, on Livia’s birthday. The dates of religious dedications were important in ancient Rome and this clearly associated the altar with her person. The altar depicts Augustus’s extended family as the family of Rome, and Livia is the key female figure in the center of the familial procession. It is also apparent that the fertile female nursing two young boys is clearly meant to be a goddess (perhaps Pax) which also alludes to Livia and her maternal role in the Roman state.

The Murderous Mother

However, while contemporary sources patronized by the imperial family present Livia in this idealized way, later sources give the empress a darker side. They suggest that she was an ambitious and pushy mother determined to make her son Tiberius emperor, suggesting she would stop at nothing, even murder.

First, Livia is accused of being behind the death of Augustus’s first chosen heir, his nephew Marcellus, who died from illness in 23 BCE. While contemporary sources are silent, the 3rd-century historian Cassius Dio said she killed him, “ … because he had been preferred before her sons (53.33).”

Livia’s eldest son, a 17-year-old Tiberius, officially entered politics as a quaestor in 24 BCE. Augustus also secured permission for him to stand for praetor and consul five years before the usual age. However, following Marcellus’s death in 23 BCE, Augustus was concerned about his health and apparently considered Tiberius too young to be his heir. Instead, he chose his friend Agrippa, whom he married to his daughter and Marcellus’s widow Julia, and gave command of the empire’s eastern provinces. Livia was not implicated in Agrippa’s death while on campaign in 12 BCE, but Tiberius was elevated as his replacement. He was married to Julia and given important commands in Pannonia and Germania.

But while Augustus favored his 30-year-old stepson, who proved himself a capable general, he also had his eye on his grandsons, the sons of Julia and Agrippa, Gaius and Lucius Caesar. He adopted the infant boys as his sons and personal heirs in 17 BCE and set them on the path to power. In 6 BCE, the 14-year-old Gaius was made consul elect for the year he would be 20. The same year, Augustus intended to send Tiberius to the east, accompanied by Gaius as a military apprentice. But for unclear reasons, Tiberius quit public service and retired to Rhodes.

Surprisingly, Livia’s response to her son essentially giving up any imperial ambitions is not preserved. We are told that when her younger son Drusus fell from his horse and died in 9 BCE, she mourned him, but not so excessively as to be unseemly. She is, of course, not implicated in her son’s death, but she is accused of killing Gaius and Lucius, who died under similar circumstances. Lucius died in 2 CE, falling from a horse during military training in Gaul. Gaius died in 4 CE from injuries sustained while campaigning in the east. The 2nd-century historian Tacitus says:

“When Agrippa gave up the ghost, untimely fate, or the treachery of their stepmother Livia, cut off both Lucius and Gaius Caesar, Lucius on his road to the Spanish armies, Gaius—wounded and sick—on his return from Armenia. Drusus had long been dead, and of the stepsons Nero (Tiberius) survived alone (1.3.2).”

Cassius Dio notes that Livia was suspected because Gaius’s death coincided with Tiberius’s return to Rome. But before his death, Gaius had told Augustus that he planned to retire from public life due to physical and mental weakness caused by his injury. This is why Tiberius was recalled.

Livia is further accused of plotting to have her husband banish his daughter Julia from Rome in 2 BCE due to personal dislike and her poor treatment of Tiberius during their marriage. However, there is ample evidence of Julia’s adultery and promiscuity, which made a mockery of Augustus’s moral laws. Moreover, she was probably involved in a political conspiracy against her father. Augustus’s anger at his daughter was also widely recorded. If Livia favored her exile, Augustus seems to have needed little convincing.

Finally, both Tacitus and Cassius Dio suggest that Livia played a role in the death of the elderly Augustus, reportedly smearing poison on fresh figs on the branch to avoid detection. Considering Augustus’s advanced age and ailing health in 14 BCE, and the fact Tiberius was now his clear successor, Livia did not have a good reason to kill her husband of 50 years.

The only murder in which she is potentially convincingly implicated is that of Agrippa Posthumous, the final son of Julia and Agrippa and a potential rival to Tiberius for power. The 26-year-old was killed after Augustus died but before the old emperor’s death was announced to the public, suggesting he was killed to make way for a clear succession. The young Agrippa had been adopted in 4 CE, but exiled in 6 CE, apparently under Livia’s influence, for his unsavory character. While Tiberius or Livia may have had him killed, some historians suggest they were acting on Augustus’s dying wishes, to protect the empire against potential civil war.

Therefore, the murderous accusations against Livia seem unfounded. Moreover, the accusations only appear in sources written after the fall of Nero, whose mother Agrippina was ruthless in the promotion of her son Nero, and probably her husband Claudius. Agrippina created the stereotype of an ambitious and murderous imperial woman, which seems to have been retrospectively applied to Livia.

Dowager Empress

When Augustus died in 14 BCE, Livia did not fade into the background. If anything, she became a more prominent figure in Roman politics. This seems to have been a challenge for Tiberius, who was determined to follow Augustus’s advice to keep the honors that he and his mother received in check, and who must have struggled with a mother who seems to have considered herself his equal in power.

In his will, Augustus adopted Livia into the Julian family, which was an honor for her and would have strengthened Tiberius’s claim to power. The Senate also voted Livia many honors both directly after Augustus’s death and in subsequent years. Her wedding anniversary to Augustus and her birthday became public holidays and she was given permission to sit among the Vestal Virgins in the theater. Tiberius also rejected many honors for both himself and his mother as excessive. For example, he rejected the titles mater patriae for his mother and pater patriae for himself.

Tiberius ensured that Augustus, like Julius Caesar before him, was deified as Divus Augustus, and Livia became his first priestess. The Senate voted that she should be accompanied by a lictor, a symbol of political power associated with Roman magistrates. Livia received the title Augusta, as Tiberius himself became Augustus, which seems to put them on an equal footing, or at least that seems to have been Livia’s interpretation.

Livia, now officially Livia Julia Augusta, seems to have enjoyed exercising power in her own right. She held formal audiences with ambassadors and signed agreements with vassal states alongside her son. Her soft power in Roman politics was also far-reaching. Tacitus and Cassius Dio suggest Livia’s overbearing actions led Tiberius to retire to Capri in 26 CE, following the deaths of his nephew and adopted son Germanicus and his biological son Drusus.

Whether Livia was the cause is unclear, as Tiberius had already shown his reclusive nature when he retired to Rhodes in 6 BCE. It is equally possible that Tiberius was happy to leave his mother in charge of certain things in Rome alongside his praetorian prefect, Sejanus. It seems to have been Livia’s influence that kept Sejanus in check since it was only after her death that Sejanus overreached, and Tiberius had him killed.

However, under Tiberius, the sources yet again accuse Livia of murder, this time of Germanicus. He was her grandson, the son of Tiberius’s brother Drusus, whom Tiberius adopted as his heir following Augustus’s instructions. While Germanicus was popular, he was not an overly effective general. Therefore, when Tiberius granted him power over the eastern provinces, he also sent his trusted ally Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso to babysit. The sources suggest that this was Livia’s idea and that Piso was her creature.

Germanicus, and even more so his wife Agrippina, another daughter of Julia and Agrippa, seem to have been unhappy with this oversight. When Germanicus fell ill and died, Agrippina accused Piso of killing her husband. Piso was tried, and while not convicted of murder, committed suicide. Nevertheless, this is another unlikely accusation. Germanicus was a beloved grandson and his eldest sons, Drusus and Nero, were recommended to the Senate as potential successors in the years following his death. But Agrippina was unable to accept the situation and may have conspired against Tiberius, leading to her exile, and later that of her two eldest sons. Agrippina’s remaining children were left in Livia’s care. She ensured excellent marriages for the girls, and Gaius Caligula lived with her until her death, after which he went to live with Tiberius in Capri and was groomed as his successor.

Diva Augusta

When Livia fell ill in 22 CE, Tiberius rushed back to Rome to be by her side as she recovered. When she fell ill again in 29 CE, he did not return to Rome, and he did not return for her funeral when she died at 86 years old. It was left to the young Gaius Caligula to give her funeral oration. It is unclear whether this means that their relations had soured, or if Tiberius simply no longer had the stomach to return to Rome.

The Senate suggested divine honors for Livia, which Tiberius blocked, professing to be following her wishes. It is very likely that they had discussed her posthumous honors and agreed on what was appropriate.

When Gaius Caligula became emperor, he claimed to execute Livia’s will, which he said Tiberius had neglected to do. This did not include deification for his great-grandmother, lending support to the idea that she accepted that her posthumous honors would be mortal. The mortal nature of her posthumous treatment is reinforced by the fact that public mourning was declared among women. Tiberius had specifically prohibited public mourning following Augustus’s death, as the gods should not be mourned.

Nevertheless, Livia was eventually deified when Claudius unexpectedly came to power in 41 CE. Unlike Tiberius, who had been adopted into the Julian gens, and Gaius Caligula, who was a great-grandson of Augustus via his mother Agrippina, Claudius, another son of Tiberius’s brother Drusus, had no ties to the Julian gens. Consequently, he had to promote the Claudian side of the Julio-Claudian Dynasty, which meant his grandmother Livia. He had her deified and included her alongside Divus Augustus in his temple as Diva Augusta. From that day, she received sacrifices for the good of the imperial family and the state alongside Divus Augustus, and the Vestal Virgins were charged with maintaining proper sacrifices in her name.

But long before her official deification, like many other members of the imperial family, Livia was a semi-divine figure. It was not uncommon in Greco-Roman culture for very powerful figures to be venerated in a similar fashion to the gods, so it is not surprising to see evidence of Livia’s worship in domestic household cults and across Italy and the provinces. In household cults, it was common to worship the genius (a kind of guardian spirit) of the paterfamilias of the household, and the genius of the emperor. There is evidence of worship of Augustus’s genius and the juno of Livia, which was the female equivalent. Ovid describes how he had silver figures of Divus Julius, Augustus, and Livia in his household shrine, and he prayed to them daily for his return from exile (he was banished to the Black Sea in 8 CE).

Many of Rome’s provinces also had cult centers dedicated to the imperial family. In 29 BCE, the province of Asia set up a temple to Augustus and Roma at Pergamum. Later, a statue of Livia was included in the temple. An inscription also records that her birthday was celebrated, not on her own birthday, but with Augustus on his birthday. After the death of Augustus, Tiberius allowed the province to dedicate a temple to himself, Livia, and the Roman Senate.

The Julio-Claudian Empress

Livia was the first Roman empress and set the standard for future imperial women. They had the power to persuade, but they always stood behind the emperor and were vilified when they overstepped the mark. They were also important when it came to establishing imperial bloodlines, especially Livia’s, who was the only person to hold the title Augustus, or Augusta in her case, to be related to every Julio-Claudian emperor. She was the wife of Augustus, the mother of Tiberius, the great-grandmother of Gaius Caligula, the grandmother of Claudius, and the great-great-grandmother of Nero. She was the backbone of the Julio-Claudian Dynasty.

Selected References

Deckman, A. (1925) “Livia Augusta,” Classical Weekly 19.3, pp 21-25

Grether, G. (1946) “Livia and the Roman Imperial Cult,” American Journal of Philology 67.3, pp 222-252.