A document that Harvard University purchased for less than $30 might actually be worth millions. According to new research, the document is not a replica, as was previously believed. Rather, it has now been authenticated as an original Magna Carta issued by King Edward I in 1300.

The History and Legacy of Magna Carta

Originally signed by King John in June 1215, Magna Carta was the first document to put into writing the principle that a king and his government were not above the law. Latin for “Great Charter,” the landmark legal document established fundamental rights and liberties for English citizens, particularly those of noble rank.

While Magna Carta did not immediately secure peace in medieval England, it laid the foundation for the development of individual rights, representative government, and constitutional law—not just in England, but throughout the English-speaking world. For example, the Fifth Amendment to the US Constitution, which guarantees due process of law, was directly influenced by Magna Carta.

Magna Carta went through six different iterations throughout the 13th century, with the final version dated to 1300. Today, only four original copies of the 1215 Magna Carta survive. Two are held in the British Library, and the others are at Lincoln Castle and Salisbury Cathedral.

How Did Researchers Authenticate the Medieval Document?

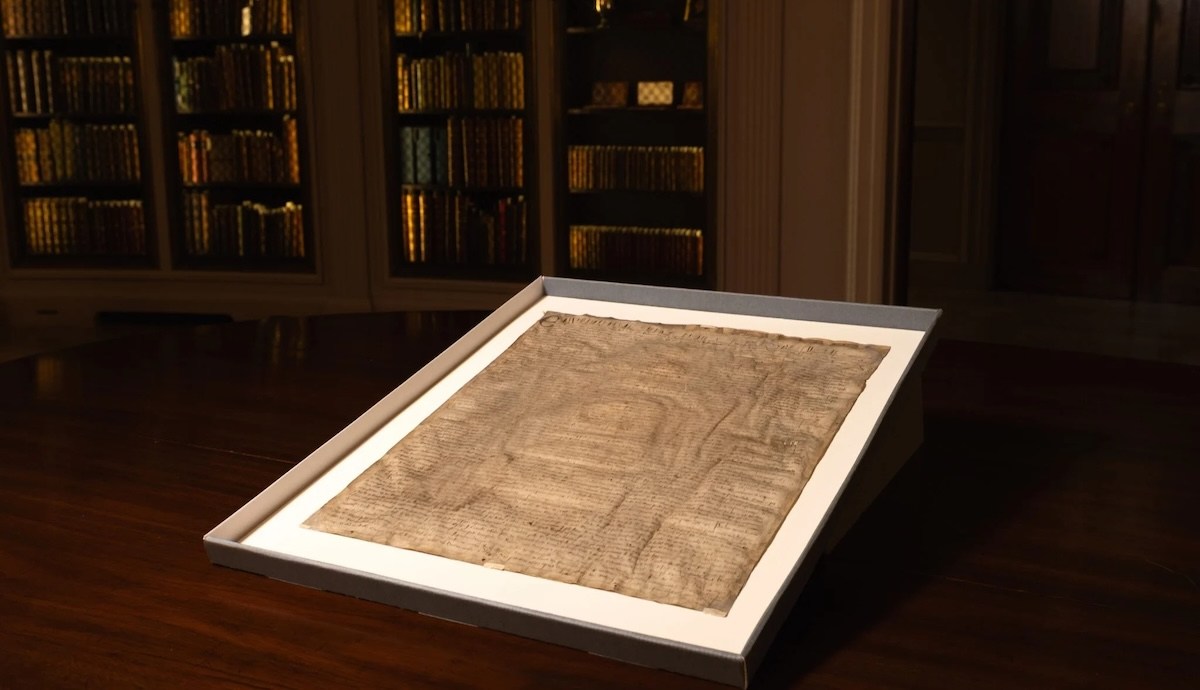

In 1946, Harvard University paid a London bookseller just $27.50 (equivalent to about $460 today) for what it believed was a replica of Magna Carta. The document, since held in the archives of the Harvard Law Library, went unnoticed until now. David Carpenter, a medieval history professor at King’s College London, began scouring the digitized collections of US university libraries to find unofficial copies of Magna Carta. His original aim was to study the legislative influence of the document based on the appearance of copies in collections such as the Harvard Law Library.

However, when Carpenter discovered the digitized image of Harvard’s supposed replica, “I immediately thought: my God, this looks for all the world like an original of Edward I’s confirmation of Magna Carta in 1300.” Carpenter collaborated with Nicholas Vincent, a peer at the University of East Anglia, to compare Harvard’s Magna Carta with the six other official versions that Edward I had issued in 1300. They first determined that the document’s exact dimensions—489 by 473 millimeters—were consistent with the known originals.

Because Harvard’s Magna Carta was “somewhat rubbed and damp-stained,” Carpenter and Vincent used spectral imaging technology and ultraviolet light to decipher the document’s Latin text word by word. They found it to be a perfect match to the other 14th-century originals. This match was critical because the clerks who produced the documents were instructed to meticulously copy a single template. Additionally, the Harvard version presents the king’s name, Edwardus, with the E and D both capitalized—an unusual feature that also appears on the other six documents.