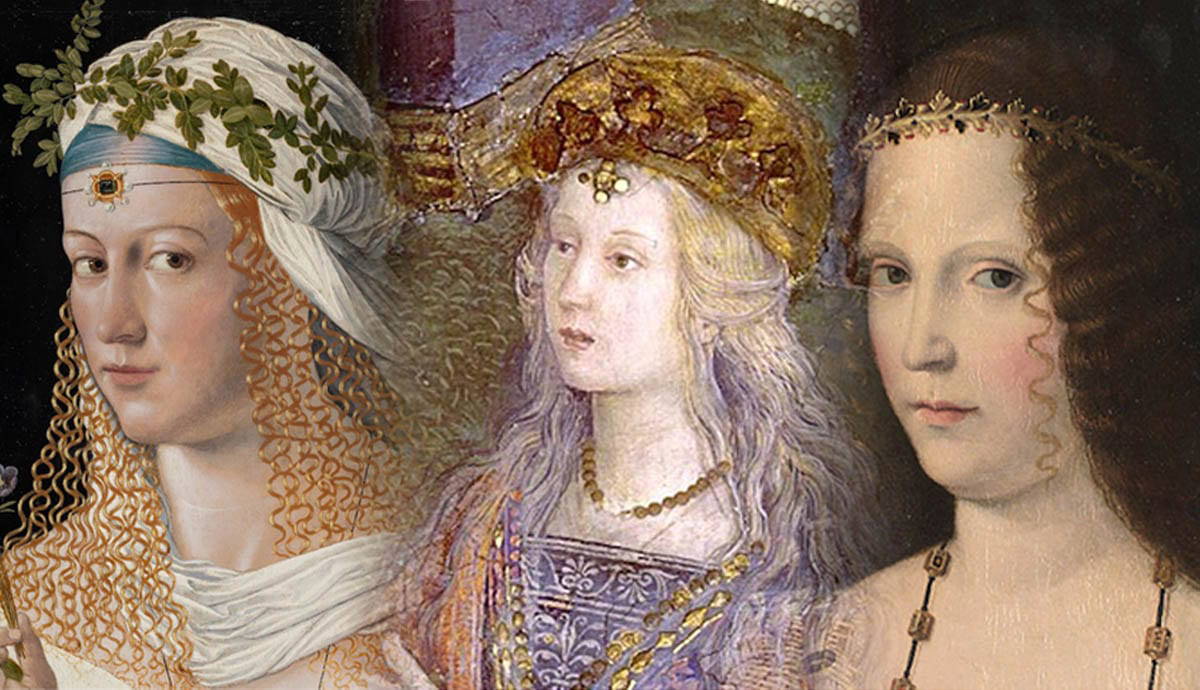

Images of Lucrezia Borgia have been reproduced decades after her death portraying her as a sensual and conniving person. These images reveal how the public views this iconic Renaissance woman. But how accurate are these depictions of Lucrezia? Scholars and critics have debated and searched for an image that shows her physical likeness and personal identity. Here are five of the most widely used Renaissance portraits of Lucrezia that range from the early to final years of her life.

Piety And Purity: Lucrezia Borgia As St. Catherine Of Alexandria

One of the earliest possible Renaissance portraits of Lucrezia Borgia is located within the Vatican. Bernardino di Betto (Pinturicchio) was assigned by Lucrezia’s father, Pope Alexander VI to create a series of frescoes within the Borgia Apartments. They are painted within a series of six suites that are located at the Apostolic Palace of the Vatican, which is now part of the Vatican Library. The frescoes were completed between 1492 and 1494, so Lucrezia would have been around 12-14 years of age. Here, she is portrayed as St. Catherine of Alexandria in Disputation of St. Catherine of Alexandria.

A woman’s association with piety and purity was crucial in the way they were perceived. Portraying Lucrezia as St. Catherine is not a random coincidence. Connections between her and heavenly religious figures are intentional to solidify her status as a well-brought-up woman. This is something that would continue to define Lucrezia’s character throughout her life. She was known as being devoted to the Church and spent time in convents when she was stressed/ill and needed refuge. Her piety was well-known even through the persistent rumors about her family.

Other frescoes contain portraits of various figures from the family including her father Rodrigo Borgia, her brother Cesare Borgia, and her father’s mistress Giulia Farnese. Above is a section from The Resurrection featuring Pope Alexander VI as himself in prayer. Since other members of her family are included in the frescoes it’s possible that she is also portrayed here as well. Pope Alexander VI was not the first Pope to be placed in religious frescoes, but he was the first to place his family in them. After becoming Pope he legitimized his children as his own and used their newly found positions to create a dynasty for his family. For Lucrezia, this meant advantageous marriages. A Renaissance portrait such as this would have been viewed by visitors of the Pope. It contributed to the image Pope Alexander VI set for his daughter and family.

Two Medals Same Person: Commemorative Medals Of Lucrezia Borgia

Two separate medals, both depicting Lucrezia Borgia, are attributed to the artist Giancristoforo Romano. Medals in the Renaissance were often made to commemorate weddings, anniversaries, deaths, or celebrations of a person. The Renaissance revitalized classical Roman traditions, and commemorative medals were one such tradition. They allowed people of importance to be recognized and their likeness to be immortalized on these medallions. The inscription translates to “Lucrezia Borgia d’Este Duchess” and is circa 1502-05 depending on the source.

During her procession into Ferrara, her new home, it was important to display the wealth that her family was bringing into the marriage. To command attention and make a statement was essential in making lasting first impressions. This medal certainly showcases her wealth and fashion sense that she brought with her from Rome.

The medal on the left appears to be a medal made for the marriage of Lucrezia and Alfonso I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara in early 1502. Isabella d’Este, Marchioness of Mantua, Lucrezia’s sister in law, detailed what she wore on the event of her marriage and arrival to Ferrara. One of her accounts notes her headdress “was loaded with spinels, diamonds and sapphires and other precious stones, including very large pearls” (Quoted from Sarah Bradford’s book Lucrezia Borgia: Life, Love, and Death in Renaissance Italy).

This description lines up with what is pictured on the left medallion. Her hair is made in a coazzoni hairstyle, a popular hairstyle for women. It features a smoothed center-parted hair and a long plaited long braid. She is wearing a trinzale (a fashionable hair net usually with pearls or beads) along with a lenza, which is the cord worn around like a headband. Above is a portrait of Bianca Maria Sforza that also demonstrates this hairstyle.

In 1505, both Lucrezia and her husband inherited the title of Duchess and Duke of Ferrara, so the right medal could be a commemoration of this event. The second image is very different in terms of what appearance it gives off. Here, her hair is loosely pulled back and is flowing freely down her back in waves. She is wearing a simple cord necklace around her neck. Her dress is draped and strapped with a small clasp on her shoulder called a brochetta di spalla. This appearance can be related to a Roman style. She was often associated with the Roman heroine Lucretia which plays a large part in identifying her in other portraits.

The Importance Of Dress: Portrait Of A Young Lady

Portrait of a Young Lady is another painting sourced as a possible portrait of Lucrezia Borgia. This image is used in biographical sites or online articles about Lucrezia, so it is worth mentioning. According to the National Gallery London, this is a Renaissance portrait of an unknown woman created around 1500-10. What is known is that the woman pictured is of obvious wealth because of her dress. It is speculated that this could be a portrait of Lucrezia because it was painted by Bartolomeo Veneto, the same artist who created the Idealised Portrait of a Courtesan as Flora. Vento became known for his highly detailed portraits that emphasize the clothing of the wealthy.

Sometimes we are given no indication of the identity of the person portrayed in a Renaissance portrait. It can be a difficult task to trace the original artist, owner, and sitter. It was common for painters to add symbols or heraldic images that related to a specific family. The white sleeves of the camica are decorated with golden staffs and black feathers which can be a clue as to what family she belonged to. The Borgia family’s crest contains a red bull while the d’Este family is an eagle. The decorative feature of the petal-shaped fastenings can be another clue as to the sitter’s identity. Devotional jewelry was popular during the Renaissance. The necklace seen above contains hexagonal beads that contain religious symbols from the Passion of Christ. Some jewelry pieces even contained initials of the person or a loved one.

It is unknown whether this image is of Lucrezia or another member of the d’Este family. However, it is known that Bartolomeo Veneto worked for the d’Este court in Ferrara around 1505 and 1508. By this point, Lucrezia would have been remarried to her third husband and was still in the early years of her life in Ferrara. If anything, they do showcase what style of dress was fashionable for women in high society during this time. Both Lucrezia and her sister-in-law Isabella d’Este were well-known for their fashion sense and set trends within their respective courts. There was even a rivalry between the two based on not only looks but fashion trends.

The Idealized Woman: Idealised Portrait Of A Courtesan As Flora

This painting is one of the more popular portraits believed to be of Lucrezia Borgia created by Bartolomeo Veneto. It is because of the woman’s distinct and stylized golden hair that people reference this Renaissance portrait to be of Lucrezia. The physical appearance of this woman does fit with the few descriptions that we have of her. The pale skin, fair hair, and graceful quality of this portrait resemble who she was during her life. The painting is speculated to have been created around 1520, so it was presumably created posthumously. Scholars argue this may not be Lucrezia because of the nature of the portrait. No ‘respectable’ lady would have worn this attire in public with its loosely draped garment, laurel wreath crown, and exposed breast. However, this portrait may not be an accurate portrayal of a woman.

It is argued that Veneto did not intend to create a portrait of an actual woman. Instead, she is supposed to be the personification of Flora, the Roman goddess of springtime. Here, she is the ideal form of beauty and sensuality. It is not her physical appearance that is important but, rather what the image itself represents – the eternal beauty as we see her in as an art form. Artists would paint portraits of women romanticized as nymphs, goddesses, or saints, thus making them more than just a woman. Other contemporary beauties of Lucrezia’s age were also painted/viewed in this manner including Giulia Farnese also known as Giulia la Bella (Julia the beautiful) and Simonetta Vespucci who was the muse of many artists including Sandro Botticelli. Paintings such as this immortalize the beauty of these women into something that goes beyond mortal boundaries.

Lucrezia’s hair seems to be a part of her identity as it is referenced in numerous sources. The Ambrosiana (a historic library in Milan, Italy) has a lock of hair that belonged to Lucrezia. When Lord Bryon visited the Library he reportedly stole a lock of her hair calling it “the prettiest and fairest imaginable.” A Renaissance woman’s identity was largely held by physical appearances as this was related to her inner beauty, in which purity and virtue were highly valued. Fair complexions and hair were desirable features in the portrayals of women.

Both written and physical poetry has had a large impact on the way Lucrezia was viewed. Even hundreds of years after her death her image and beauty were revitalized for poets like Lord Bryon during the Romantic era. Lucrezia created a court of poetry, art, and discussion in the Ferrarese court and this had a lasting impact on how people perceived her decades later as a patron of the arts.

Recent Discovery: Lucrezia Borgia, Duchess Of Ferrara

One of the most recent discoveries in identifying Lucrezia Borgia is this painting owned by the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. After years of study since its purchase by the museum in 1965, it made headlines in 2008 as the museum claimed they had the first portrait of Lucrezia.

However, it is still not accepted by all scholars as a definitive portrait of her. The artist who painted the Renaissance portrait, Dosso Dossi, was known to have lived in Ferrara between 1515-20, which coincides with Lucrezia’s time as a Duchess. The date of completion ranges from 1519-30 so if this is her, then it would have been painted near the end of her life or even posthumously. After the difficult birth of her tenth child, Lucrezia became ill and passed away not long after at the age of 39.

It was originally titled Portrait of a Youth by an unknown artist, and for many years was thought to be a portrait of a young man. The androgynous nature of the painting has led to confusion on the identity of the image. To modern viewers, it appears to be a man’s garment because of its high neckline, white collar, and leather sleeves. Dark clothing is not always reflected as mourning, but black and gold was a popular choice for Spanish nobility during the 1500s as darker colors were more expensive to dye.

Clues as to whether this is Lucrezia are shown through the objects of the portrait. Experts believe that the dagger held between her hands is a reference to the Roman woman Lucretia. She was a Roman woman who killed herself with a dagger after being raped by the son of the king of Rome, Sextus Tarquinius. Lucrezia Borgia is often compared to the Roman Lucretia not only by name but by virtue. Being compared to a woman who died in order to protect her family’s honor helps to repair a woman’s reputation that was stained by the actions/rumors of her own family.

There is also a myrtle bush, which represents Venus, the goddess of love. The myrtle bush was used as a symbol of Venus and is used almost exclusively with female portraits. The inscription in the foreground reads “brighter (than beauty) is the virtue reigning in this beautiful body” which is an adaptation of a verse from the Roman poet Virgil’s Aeneid. These symbolic and literal transcriptions of beauty are what make researchers sure that this is of a female and not a young male.

During her time as Duchess of Ferrera Lucrezia went through many life-changing events. She suffered the deaths of her father, brother, and her first son with her second husband while in Ferrera. She suffered miscarriages throughout her marriage and became increasingly pious and dedicated more time to the Church. Because of this, her style of dress and appearance was said to have changed. This is not the same 14-year old girl seen as Saint Catherine with hopeful optimism and naivety. Here, she is a woman, mother, wife, and Duchess with cares and responsibilities. The lack of jewelry, fine cloth, and the simplistic nature of the portrait could be indicative of sainthood of a different kind. Instead of being portrayed for just piety and purity, she is instead remembered for the grand woman she had become and the legacy that she would leave behind.