Manichaeism was a religion that started in the Persian Empire in the 3rd century CE that became a serious rival to early Christianity. For hundreds of years, it challenged Christianity by offering its own answers to life’s mysteries. For example, it taught that good and evil were equal forces that were always in conflict. To explain how the world works, the religion combined ideas from other faiths such as Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Christianity.

Its founder, Mani, began spreading the Manichaean gospel from around 241 CE, and over the next couple of decades, the religion spread quickly across Asia to the Roman Empire, North Africa, and China.

Integration of Christian Concepts

Its founder, Mani (216 CE to around 276 CE), was born in Babylonia, which was part of the Persian Empire. He grew up in a Jewish-Christian community but over time rejected their strict rituals. At the age of 24, Mani claimed to have received a divine vision from his twin spirit and began preaching a new universal religion. The religious founder soon began to proclaim that he was the final prophet and that he had been sent to improve and complete the teachings of earlier prophets such as Zoroaster, Buddha, and Jesus and was the Messenger of Light.

Unlike Jesus or the Buddha, Mani wrote his own sacred books. Before his death, he had written seven main books. Six in his own language and one in Persian for King Shapur I.

It Had a More Sensible Explanation of Evil Compared to Christianity

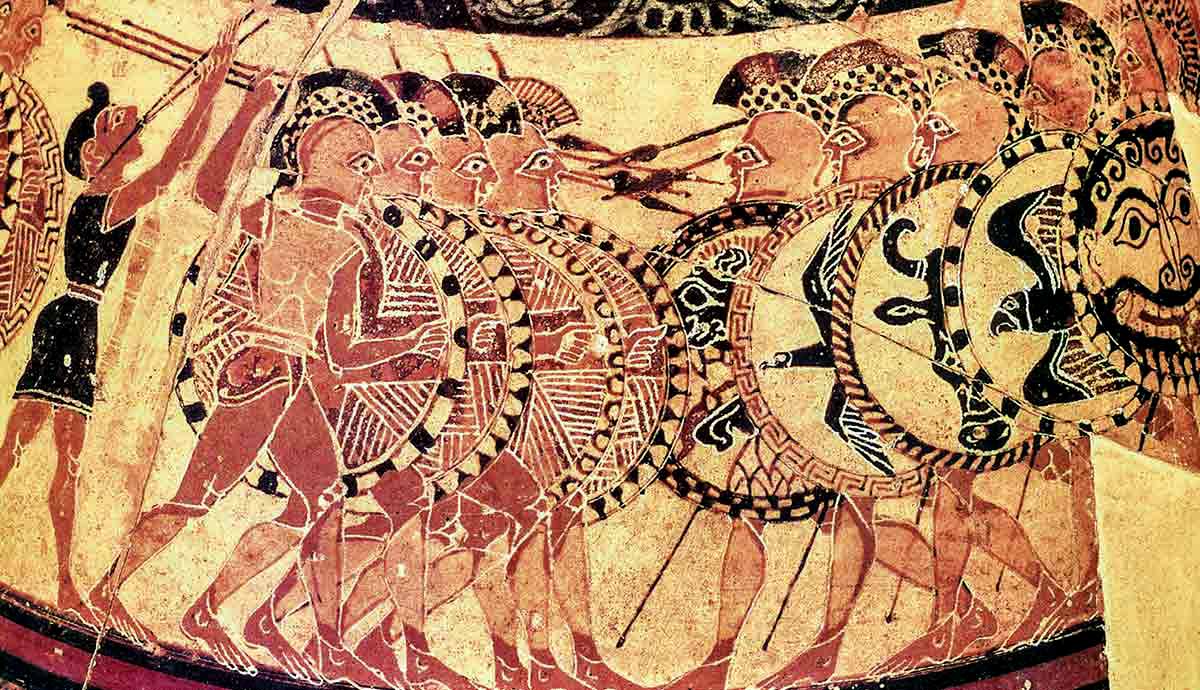

Based on ancient beliefs, Manichaeism tried to explain why pain and evil existed. It provided a detailed explanation that told of a long war between two eternal powers – the Kingdom of Light and the Kingdom of Darkness. According to the account, tiny bits of pure light got stuck inside physical matter which was evil. Manichaeism followers believed that the human soul was made up of these trapped sparks.

The logical explanation for the cause of evil attracted many followers who found Manichaeism to be more sensible compared to what Christians were teaching at the time.

It was during this period that a young man named Augustine of Hippo joined the group in Africa in 373 CE and listened closely to its teachings. He remained a low-ranking member, a Hearer, for nine years and never became a leader of the sect. While Augustine initially accepted the teachings about light and dark matter, he eventually left the group as he had too many doubts.

Years later, after converting to Christianity, he became a powerful church leader. As a Christian Bishop, he wrote many books against his previous faith and built his reputation as one of the most influential critics of Manichaeism of his time.

Its Religious Concepts Were Flexible

In Christian areas, Manichaeans taught about a spiritual, docetic Jesus – one who only appeared to have a physical body and did not truly suffer or die. This explanation, however, was rejected by most Christians as heresy. In Central Asia, the religion presented Mani as Buddha’s true successor and the final prophet after Zoroaster, Buddha, and Jesus.

This helped to create familiarity with followers of other religions. In China, it often changed its message. At one point, it claimed that Mani was actually Laozi, the legendary Chinese philosopher who is considered to be the author of the Tao Te Ching, one of the foundational texts of Taoism. According to Manichean preachers, Laozi, who had traveled west, had returned as the Buddha of Light. This level of flexibility allowed Manichaeism to spread rapidly.

How Did Manichaeism End?

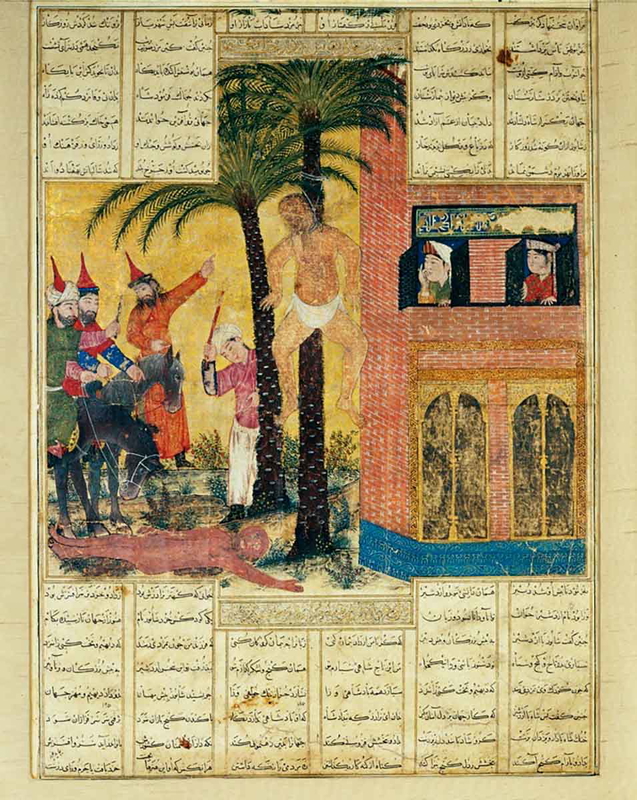

Even though Manichaeism spread quickly and attracted many followers at first, leaders and priests soon turned against it. In 277 CE, the Persian king Bahram I arrested Mani and threw him in prison, where he died about a month later after he was executed. Decades later in 302 CE, the Roman emperor Diocletian issued a new law decreeing that Manichaean leaders were to be burned alive along with their sacred books. Their followers were also to be executed or subjected to forced labor.

After Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, from the late 300s and 380s onward, laws targeting Manichaeans became even more strict. As a result, many adherents lost their property, legal rights, and sometimes their lives. By the late 500s, Manichaeism had mostly died out. Today, the religion is widely considered to be extinct.