People often have several misconceptions about medieval food. There seems to be a notion that peasants survived on crusts of stale bread and watered-down ale, while every night the lord of the manor and the kings and emperors around the globe were feasting on rich, expensive foods. While there is a certain element of truth to this, it is nevertheless important to dive into the reality behind the stereotypes that we have surrounding medieval food. Read on to discover all there is to know about what people ate during the Middle Ages.

Regional and Local Cuisines

For the purposes of this article, we will solely focus on medieval Europe. While Eurocentric, people generally associate this term with the European Medieval Period, and more commonly, the High Middle Ages, anywhere from the 12th century to the 15th century. However, we will look at the Medieval Period as a whole, and use examples from different regions in Europe.

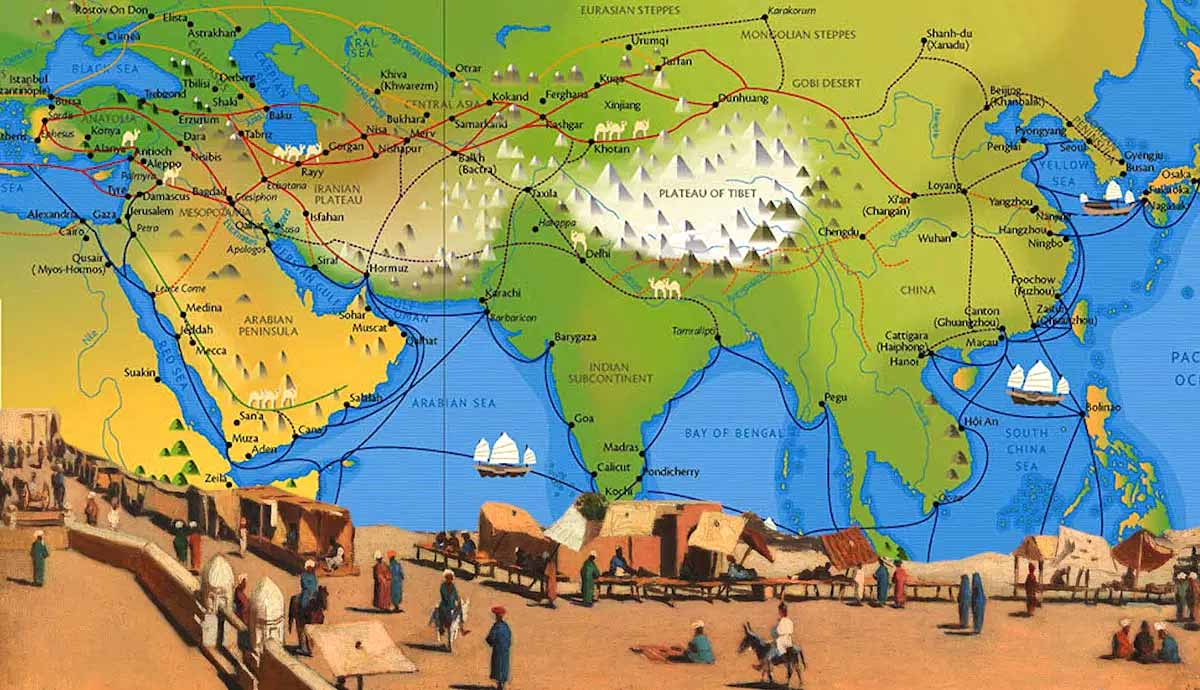

Like today, the cuisine eaten in northern Europe varied hugely from that in southern Europe, due to the resources that were available. Of course, trade played a huge role in the medieval diet, and once the spice trade was opened up from places such as China and India via the Silk Roads (and later, the Americas and the Spice Wars which dominated the Early Modern world) it helped to influence medieval cuisines regardless of location in Europe.

What is more interesting to note is that the world was much smaller in the Middle Ages. Not geographically, but metaphorically—villages, towns, and small communities were much more commonplace (particularly in the British Isles), and many medieval peasants would live their whole lives in a 20-mile radius. This meant that those who lived inland would have their diets based on the crops that they could grow, while those near the coast had a diet that was heavily reliant on seafood, such as fish and shellfish.

To this day, this is still felt in the cuisines of certain towns—take Whitby, on the North Yorkshire coast for example; often regarded as the best place in Britain to get fish and chips—Whitby has been a fishing village for hundreds of years. But go further inland to places such as Lancashire, beef stew, known as Lancashire Hotpot, has been a regional dish for centuries. Small, localized communities with little interaction with other towns, parishes, and cities made the most of their local resources.

Food as a Class Divider: Peasants vs the Nobility

Of course, it would be unwise to presume that peasants in the Middle Ages ate the same foods as the nobility. The peasants’ diet largely relied on foods that they could grow, cultivate, harvest, or nurture themselves. These foods typically involved grains such as wheat—baked into bread in Northern Europe and transformed into foods like pasta in Southern Europe.

In addition, peasants typically tried to keep small animals such as chickens, which could provide them with a multitude of things—eggs, for cooking with, and when it came to slaughtering them, meat for consumption in dishes like stews or roasts. The feathers could be used in bedding.

For the nobility, it typically didn’t matter if foodstuffs were local or not. Famously, King Henry I of England died after consuming a “surfeit of lampreys” in 1135, which would have likely had to come from the coastal regions of the UK.

Moreover, the high nobility were more exposed to rich foodstuffs and foreign foods than peasants were—they could also keep their own animals for slaughtering purposes—including cows, sheep, chickens, and more. Much more meat was consumed by the nobility when compared to the peasants, and as a result, gout became known as “the disease of kings.”

While one bad harvest could kill off a peasant family or community, the nobility managed to survive. Even during the famine of 1315-17 during the reign of King Edward II, members of the court survived, and Edward would go on to rule for another ten years, while many peasants perished due to crop failures.

Meat and Fish: A Rich Man’s Food?

As mentioned earlier, the nobility ate much more meat than their peasant counterparts, partly because they could afford to have such luxuries.

Take an average peasant family—if they were lucky, they might have a cow. This cow would be used for milk, which could be used in cooking, for nursing children, and even for selling—but they could seldom afford to kill a healthy cow before it eventually died of old age. Once this cow died, the peasants could then salvage whatever meat they could from it.

On the other hand, if a king wanted roast beef for dinner, a cow could be slaughtered at any given point and roasted in the court’s huge kitchens by a dedicated team of cooks and chefs, meaning that cost and longevity were not an issue for those in the very highest echelons of society.

Fish, for peasants who lived near to the coast, was often seen as a staple, and much more readily available than meat. A good day’s fishing could provide a peasant family with enough food to see them through a month, especially if they used different preservation methods such as smoking or drying the fish to make it last for longer.

For the nobility, fish could also be seen as a luxury—especially for those courts based in inland cities such as Paris and Milan, where seafood had to be specially imported. It was seen as a sign of how wealthy and powerful the nobility in these courts were if they could provide seafood for their guests while they were miles from the coastline.

Feasting and Fasting: Religion’s Impact on the Medieval Diet

Of course, the Middle Ages was a time of high religious fervor in Europe, and many days of the year were dedicated to different saints, where feasts were often put on.

Some of the most famous medieval feast days included Midsummer Day (celebrated on June 24th, which celebrated John the Baptist), the Transfiguration of Jesus (August 6th), and of course, Christmas Day (December 25th).

The time of year that the feast was celebrated accounted for the food that would be on offer—those feasts in winter would rely heavily on meats such as beef as many freshwater lakes or rivers could have frozen over, or been too cold to catch fish. In addition, winter vegetables such as carrots and turnips would have been served.

For the summer feasts (and especially Easter), lighter meats such as lamb would have been served. In the medieval calendar, Easter was the biggest celebration by far, celebrating Jesus Christ’s resurrection, and even peasants would celebrate. The lambing season falls around Easter, so this was—and still is—the most consumed meat for Easter celebrations.

On the other hand, there were many instances of fasting, none more famous than Lent—the period of 40 days which represents how long Christ went without food in the Bible when being tempted by Satan in the desert. While peasants could seldom afford to give up any food, it was still nonetheless observed, with many going without meat for the duration of Lent.

Medieval Cooking Methods

Unsurprisingly, there were very few rules and regulations around the safety and hygiene involved in food handling in the Middle Ages.

Food was eaten as a necessity, and food poisoning could kill people much easier in the Middle Ages than it can now, so it was a big risk almost every time a meal was eaten.

Many of the cooking methods that we still use today were used in the Middle Ages, albeit with less technology due to what was available to them. Perhaps the first method that comes to mind when visualizing medieval cooking is spit roasting.

Popular throughout Europe, most meats at the time were spit roasted—from huge cattle in the kitchens of palaces and keeps, to humble chickens in the kitchens or fires of inns. Spit roasting large animals usually required two to four kitchen boys, who would rotate the meat manually so that it cooked evenly over the flames. This was a grueling job, especially during sweltering summers.

Another popular medieval cooking method was boiling. The meat was sometimes boiled alongside vegetables in dishes such as stews, which were deemed as hearty, warming meals, largely reserved for peasants rather than the nobility.

During the Middle Ages, ovens also came into play—but these were not like the commercial ovens we know today. Made out of brick and clay, these huge ovens were reserved for the finest kitchens, where loaves of bread or lots of cakes could be freshly made on a daily basis.

Medieval Food: In Conclusion

Food in the Middle Ages was not too dissimilar to the food we see today. Regional favorites are still very much prevalent, such as coastal towns offering an array of seafood, and with the advent of the Early Modern Period and the spice trade industry boom, tastes changed.

Food became more of a culinary experience from the Tudor Period onward, with huge banquets being viewed as something to make a show of, particularly during the reign of kings such as King Henry VIII who was known for his extravagant feasts.

In the Middle Ages, food was a necessity, and thus very little showiness was given to it—of course, banquets were reason enough for any noble to show off to their contemporaries, but as a general rule, food was eaten to survive, and the types of food were very demonstrative of local cuisine.