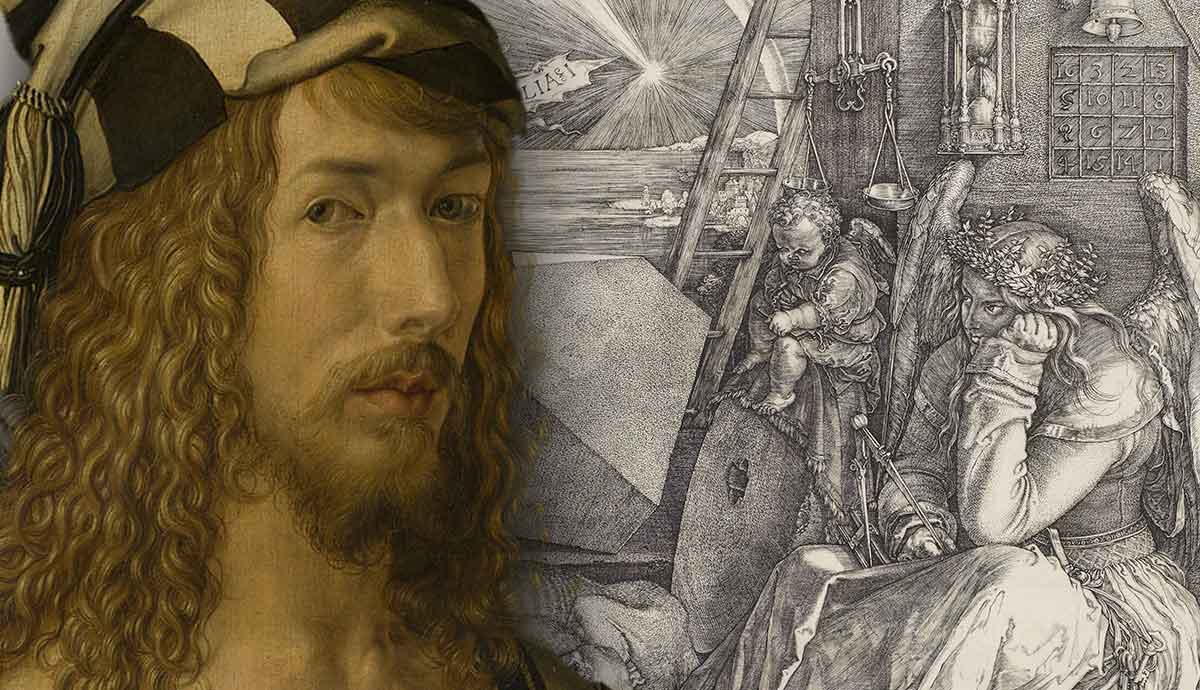

Albrecht Dürer was one of the most famous artists of the European Renaissance era. Known mostly for his drawings and engravings, he was also an art theorist, a mathematician, and a successful art businessman. Melencolia I was one of his most popular engravings, regarded universally as a great masterpiece. Its complex iconography led countless art historians to analyze and interpret its elements in search of comprehensive meaning. Read on to learn the reasons for art historians’ enduring fascination with Albrecht Dürer’s work Melencolia I.

Introduction to Albrecht Dürer’s “Melencolia I”

Albrecht Dürer was one of the most prominent artists who represented the Northern Renaissance era. The Renaissance was the time of revival of artistic and scientific principles that were first developed in ancient Greece and Rome. Like in the Middle Ages, Renaissance culture was deeply rooted in the Christian faith but demanded empirical knowledge and experiment. For Dürer’s contemporaries, harmony was based on rationality and careful calculation. Art, in particular, was regarded as a product of knowledge and mathematical precision rather than chaotic creative impulse.

Dürer was a pioneer and leader in many aspects of art production, theory, and business. He wrote treatises on geometry and proportion, studied natural history and fortification, and aimed to create the most comprehensive manual for aspiring artists. He enjoyed commercial success and took part in the political life of his community. Dürer was the first Western artist to write an autobiography, which greatly helped art historians. Although many drawings and engravings of Dürer became famous during his lifetime, Melencolia I is considered to be one of Dürer’s most complex and mysterious works due to the complex symbolism and allegories hidden within the image.

The Context of Melencolia I: Dürer’s Master Prints

Among the most widespread artistic mediums of the Renaissance era were engravings, usually etched on metal plates, treated with acid, and then printed on paper. Engravings were a relatively cheap and accessible alternative to paintings, which were easier to produce and disseminate among those who wanted to obtain a copy. Moreover, it presented more creative freedom to artists who could create without the constraints of their commissioners’ desires and sell their vision of the finished works.

Dürer was one of the pioneers of the technique and the frequent victim of art forgers due to the immense popularity of his works. The engraving plates wore out after several reprints. Yet, it was always possible for the artist to create more and extend the edition, but it also meant that almost every artist could copy an engraving by another and sell the prints as their own. To protect his art, Dürer developed a trademark, a stylized image of his initials that he incorporated in his engravings. Moreover, the artist won probably the first copyright lawsuit in Western history, as the court stated that although some elements of his work could be copied, the signature monogram was off-limits for other engravers.

Dürer created his Melencolia I in 1514 during his mature period of work, when the nuances of his style and skill had already gathered into a unified and balanced structure. The engraving was completed around the same time as two other important works of Dürer, Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513) and Saint Jerome in His Study (1514). Despite unrelated subject matter, all three are usually grouped together under the title Master Prints as the best works of the master. However, from the artist’s personal records, we know that he distributed the two works, Melencolia I and St. Jerome, together as a set.

Art historians like the legendary Erwin Panofsky believed that this was the juxtaposition of secular and religious learning: in contrast to the figure of Melancholy, uncomfortably crouched, Saint Jerome sitting behind his desk, deeply immersed in his work. However, Melencolia I’s iconographic complexity was no match for the simple and straightforward symbolism of Saint Jerome’s image.

Deciphering Melencolia I

Melencolia I consists of a large number of separate elements that require attention and analysis. The dominant figure of the composition is a winged woman in a watercress wreath. Her dress looks like something worn by a Dürer’s contemporary. In her hands she holds a compass, a closed book, and keys and a coin purse are strapped to her belt. She is surrounded by an array of geometric and artistic instruments but pays no attention to them. Behind her, a winged child, known as a putto in Western tradition, is scribbling something on a wooden board while seated atop a grindstone.

Behind both of them, there is a strange collection of objects—a scale, an hourglass, and a table filled with numbers, known as a magic square. A ladder leading somewhere outside of the picture frame in the direction of the endless sky is empty, as no one attempts to climb it. A skinny dog lies at the woman’s feet, similarly uninterested in anything and succumbing to the overall mood.

The background of the work is similarly detailed and adds more complicated elements to the entire structure. The calm surface of the sea is illuminated by a bright comet falling from the sky and a full rainbow over it. Next to the comet, a giant bat spreads its wings, on which the artist places the work’s title.

Symbolism and Meanings: Unraveling Dürer’s Mysteries

Melencolia I is believed to be the most extensively discussed engraving not only in Albrecht Dürer’s oeuvre but in the entire discipline of art history. Still, it leaves many questions unanswered. One of the most mysterious and complex details of the engraving is the magic square in the upper right corner of the composition. Magic squares were a popular recreational exercise in the Renaissance era and presented square tables filled with numbers in such a way that the numbers’ sums would be equal on all horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines. Apart from solely mathematical purposes, such squares were sometimes used as occult tools aimed to attract particular angels, demons, or planets’ influences. Dürer’s square is believed to be the earliest one to appear in visual art. The configuration of numbers suggests that it appealed to the planet Jupiter, which was deemed useful for fighting melancholy.

Art historians usually interpret the winged woman in the front plane as a personification of melancholy or a muse eagerly waiting for inspiration while afraid it would never come. The putto figure in the background further emphasizes such artistic crises, signifying thought unsupported by action. Some even believe that the woman is a spiritual self-portrait of Dürer, all too familiar with artistic crises.

The background comet might refer to the event that occurred in late 1513. In December, Dürer and his contemporaries witnessed a comet and interpreted it as an almost apocalyptic sign of upcoming tragedies and catastrophes. Generally, the chaotic, although carefully planned, placement of many elements creates the feeling of overwhelming anxiety and deep crisis. None of the instruments depicted function properly; even the hunting dog lies down passively and weakly like another object.

The Influence of Dürer’s “Melencolia I”

Melencolia I was not only a commercially successful work but also an image that formed its own cult following among other artists who reinterpreted and reused it. The motifs of artistic struggle and the heavy weight of creative talent were too familiar for many. Fifty years after Dürer, Dutch engraver Jacob de Gheyn created his own Melancholy as part of the series on human characters and temperaments. Although his figure was clearly male, its position and the air of despair and depression matched the original artwork. Three centuries later, Caspar David Friedrich would reinterpret Dürer’s figure as a symbol of grief and mourning in The Woman with The Spider Web. The famous modernist Giorgio de Chirico made a more subtle reference in his 1912 Melancholia, with an antique sculpture in an empty square crouched in a similar position.

A striking parallel to Dürer’s engraving appears in Raphael’s fresco The School of Athens. There, Raphael depicted the philosopher Heraclitus (often regarded as a portrait of Michelangelo) using the same classic melancholic pose that Dürer would later immortalize in his masterpiece. Moreover, Melencolia I transitioned from art and art history to popular culture. In 2009, it appeared in Dan Brown’s novel The Lost Symbol, in which the main character solves the riddle using the numbers in Dürer’s magic square.